The ins, outs and upside downs of Digital Research Services and lessons learned in the process.

I’ve spent the past three months working as a Researcher-in-Residence for Digital Research Services (DRS) at the University of Edinburgh, marking a transition from the completion of my PhD in which I stumbled my way through digital techniques, to the next exciting step in my career pathway as a training fellow for the Centre of Data, Culture and Society. This progression was greatly assisted by the experiences I acquired during my time with DRS, brief though it was. In particular, through reflection, awareness and facilitation of digital services and the research lifecycle in general, I developed a greater understanding of what digital research can offer, but also the roadblocks we’re slowly overcoming to get everyone there.

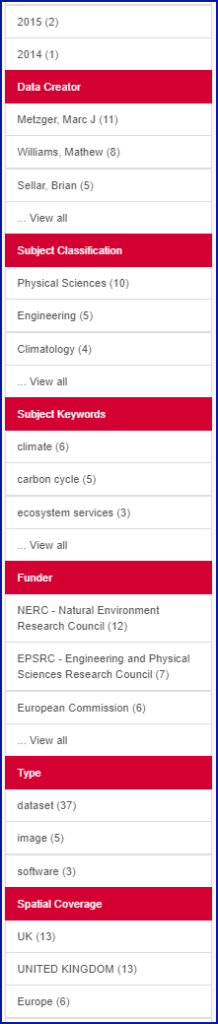

I came into this role as an emerging scholar in digital humanities, still getting to grips with the possibilities out there and slowly recognising the value the digital world harbours – a value I had previously dismissed or simply wasn’t aware of during my undergraduate studies. It is of course very easy to stand safely on solid ground, and reject the gleaming digital world over on the other side. Yet, over the weeks I’ve spent with DRS, I’ve seen various toolkits and techniques come past that could have been so useful, if I’d only known or gone looking for them. More than once, I’ve had a ‘wait, you can do that?’ moment when investigating different options available to the academic community. We are very fortunate to have so many amazing resources available right at our fingertips, thanks to the wide range of services the University provides access to, and I can strongly encourage anyone pondering the choice to go digital to give it a try! After all, there’s nothing to lose, and in the process you might discover that there are more effective ways to share your data with others (i.e. DataShare), safer and more secure ways to store and archive it (e.g. DataStore or DataVault), and faster and more reliable methods to analyse it that won’t destroy your personal device (meet Eddie or Eleanor some time).

This however alludes to the second major realisation I acquired, which is the importance of outreach and engagement to bring researchers over to the digital side. There’s no escaping the fact that researchers won’t go looking for digital assistance if they’re unaware that it’s available in the first place. This has been a major part of my role over the summer, and I’ve come to appreciate just how difficult this is within an organisation that is as multi-layered, complex and vast as the University service support system. Not only do we want to highlight our services to the target users themselves, but we also want to facilitate beneficial bridges between various organisational teams within the University network and DRS. Yet incorporating our events, trainings and seminars into their training centres, Learn pages and SharePoint sites is no small task! Nonetheless, by doing so we can provide the missing links or training that research communities are seeking, and augment pre-existing frameworks to develop a more holistic programme, that addresses needs across the diverse spectrum of applied research. This goal has been gaining traction, so watch this space (or rather, your inboxes) for more information in the coming academic year.

Finally, the third major insight I acquired concerned the current lack of digital equity within the research community. There is a certain reluctance that particular research communities or individuals have towards digital techniques. Yet, why people would avoid using tools that could make their research easier, faster, replicable and more statistically powerful? After all, despite the higher risk, most of us would opt for motorised transport these days rather than a horse and cart. Through cross-disciplinary discussions and peer-to-peer feedback, it became clear this reluctance didn’t stem from dislike or disinterest, but rather a lack of the right skillset and knowledge to approach digital tools. I myself was fortunate to have had enough of a digital background to take the necessary steps for my own PhD project, as some of the foundational stepping-stones had already been laid for me. For those coming from zero however, this is not so much a step as a leap of faith, and nobody likes ending up stuck in the mud. Adequate information and tailored training that speaks to these concerns, introduces researchers to the tools available, and guides them through digital services is a keystone in our aim to create a ‘DRS for everyone’. This will also be reflected in the calendar of DRS events for the upcoming academic year, and if you’re curious or keen to develop your digital skillset, then make sure to check out our webpage, and social media (X and LinkedIn) for updates and information about these events.

And so finishes my three months with DRS. A great opportunity to bring a little more attention to this fantastic service within the University, a chance to help other academics push their research into new territory, and a catalyst for changing the way I will approach research in the future. In the process, I can only hope this position has facilitated a few more bridges between various CAHSS communities within the University and the world of digital research on the other side. Hopefully, with time there will be fewer wet socks and more digital successes in the future.

Sarah Van Eyndhoven

Researcher-in-Residence

Digital Research Services