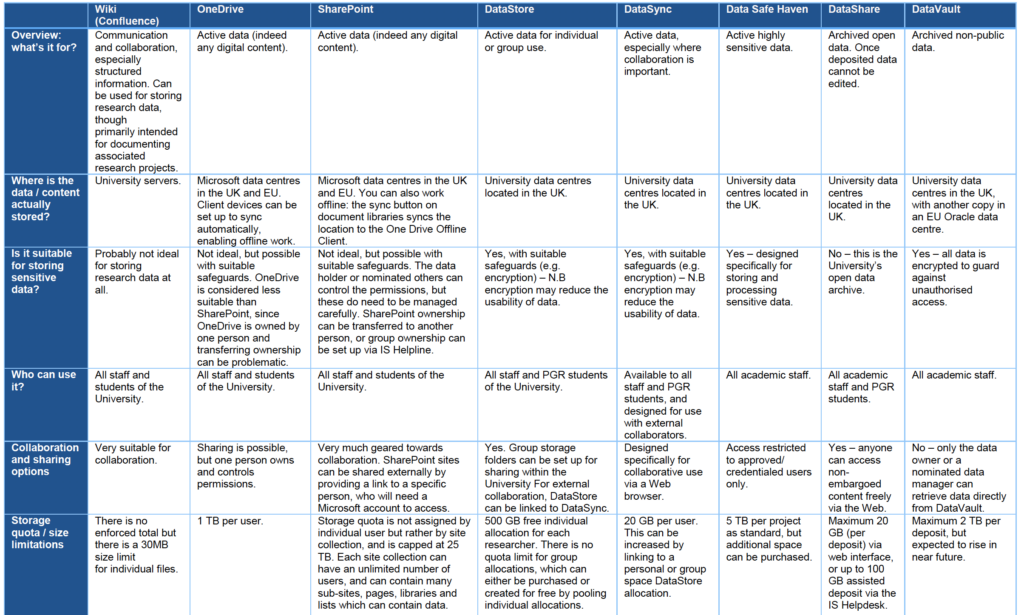

Earlier this week we bid farewell to our intern for the past four weeks, Dr Tamar Israeli from the Western Galilee College Library. Tamar spent her time with us carrying out a small-scale study on the collaborative tools that are available to researchers, which ones they use in their work, and what support they feel they need from the University. One of Tamar’s interviewees expressed a view that “[the University’s tools and services] all start with ‘Data-something’, and I need to close my eyes and think which is for what,” a remark which resonated with my own experience upon first starting this job.

When I joined the University’s Library and University Collections as Research Data Support Manager in Summer 2018, I was initially baffled by the seemingly vast range of different data storage and sharing options available to our researchers. By that point I had already worked at Edinburgh for more than a decade, and in my previous role I had little need or obligation to use institutionally-supported services. Consequently, since I rarely if ever dealt with personal or sensitive information, I tended to rely on freely-available commercial solutions: Dropbox, Google Docs, Evernote – that sort of thing. Finding myself now in a position where I and my colleagues were required to advise researchers on the most appropriate systems for safely storing and sharing their (often sensitive) research data, I set about producing a rough aide memoire for myself, briefly detailing the various options available and highlighting the key differences between them. The goal was to provide a quick means or identifying – or ruling out – particular systems for a given purpose. Researchers might ask questions like: is this system intended for live or archived data? Does it support collaboration (increasingly expected within an ever more interconnected and international research ecosystem)? Is it suitable for storing sensitive data in a way that assures research participants or commercial partners that prying eyes won’t be able to access their personal information without authorisation? (A word to the wise: cloud-based services like Dropbox may not be!)

[click the image for higher resolution version]

Upon showing early versions to colleagues, I was pleasantly surprised that they often expressed an interest in getting a copy of the document, and thought that it might have a wider potential audience within the University. In the months since then, this document has gone through several iterations, and I’m grateful to colleagues with specific expertise in the systems that we in the Research Data Service don’t directly support (such as the Wiki and the Microsoft Office suite of applications) for helping me understand some of the finer details. The intention is for this to be a living document, and if there are any inaccuracies in this (or indeed subsequent) versions, or wording that could be made clearer, just let us know and we’ll update it. It’s probably not perfect (yet!), but my hope is that it will provide enough information for researchers, and those who support them, to narrow down potential options and explore these in greater depth than the single-page table format allows.

With Tamar’s internship finishing up this week, it feels like a timely moment to release the first of our series of “Quick Guides” into the world. Others will follow shortly, on topics including Research Data Protection, FAIR Data and Open Research, and we will create a dedicated Guidance page on the Research Data Service website to provide a more permanent home for these and other useful documents. We will continue to listen to our researchers’ needs and strive to keep our provision aligned with them, so that we are always lowering the barriers to uptake and serving our primary purpose: to enable Edinburgh’s research community to do the best possible job, to the highest possible standards, with the least amount of hassle.

And if there are other Guides that you think might be useful, let us know!

- Download the Quick Guide on Research Data Storage Options

- UPDATE: the new Guidance page is now live

—

Martin Donnelly

Research Data Support Manager

Library and University Collections