As an academic support person, I was surprised to find myself invited onto a roundtable about ‘The Ethics of Data-Intensive Research’. Although as a data librarian I’m certainly qualified to talk about data, I was less sure of myself on the ethics front – after all, I’m not the one who has to get my research past an Ethics Review Board or a research funder.

The event was held last Friday at the University of Edinburgh as part of the project Archives Now: Scotland’s National Collections and the Digital Humanities, a knowledge exchange project funded by the Royal Society of Edinburgh. This event attracted attendees across Scotland and had as its focus “Working With Data“.

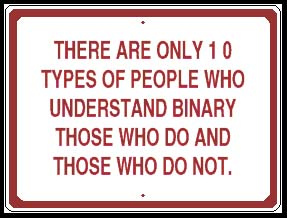

I figured I couldn’t go wrong with a joke about fellow ‘data people’ with an image from flickr that we use in our online training course, MANTRA.

‘Binary’ by Xerones on Flickr (CC-BY-NC)

Appropriately, about half the people in the room chuckled.

So after introducing myself and my relevant hats, I revisited the quotations I had supplied on request for the organiser, Lisa Otty, who had put together a discussion paper for the roundtable.

“Publishing articles without making the data available is scientific malpractice.”

This quote is attributed to Geoffrey Boulton, Chair of the Royal Society of Edinburgh task force which published Science as an Open Enterprise in 2012. I have heard him say it, if only to say it isn’t his quote. The report itself makes a couple of references to things that have been said that are similar, but are just not as pithy for a quote. But the point is: how relevant is this assertion for scholarship that is outside of the sciences, such as the Humanities? Is data sharing an ethical necessity when the result of research is an expressive work that does not require reproducibility to be valid?

I gave Research Data MANTRA’s definition of research data, in order to reflect on how well it applies to the Humanities:

Research data are collected, observed, or created, for the purposes of analysis to produce and validate original research results.

When we invented this definition, it seemed quite apt for separating ‘stuff’ that is generated in the course of research from stuff that is the object of research; an operational definition, if you will. For example, a set of email messages may just be a set of correspondences; or it may be the basis of a research project if studied. It all depends on the context.

But recently we have become uneasy with this definition when engaging with certain communities, such as the Edinburgh College of Art. They have a lot of digital ‘stuff’ – inputs and outputs of research, but they don’t like to call it data, which has a clinical feel to it, and doesn’t seem to recognise creative endeavour. Is the same true for the Humanities, I wondered? Alas, the audience declined to pursue it in the Q&A, so I still wonder.

“The coolest thing to do with your data will be thought of by someone else.” – Rufus Pollock, Cambridge University and Open Knowledge Foundation, 2008

My second quote attempted to illustrate the unease felt by academics about the pressure to share their data, and why the altruistic argument about open data doesn’t tend to win people over, in my experience. I asked people to consider how it made them feel, but perhaps I should have tried it with a show of hands to find out their answers.

Quote by John Perry Barlow, image by Robin Rice

I swiftly moved on to talk about open data licensing, the choices we’ve made for Edinburgh DataShare, and whether offering different ‘flavours’ of open licence are important when many people still don’t understand what open licences are about. Again I used an image from MANTRA (above) to point out that the main consideration for depositors should be whether or not to make their data openly available on the internet – regardless of licence.

By putting their outputs ‘in the wild’ academics are necessarily giving up control over how they are used; some users will be ‘unethical’; they will not understand or comply with the terms of use. And we as repository administrators are not in a position to police mis-use for our depositors. Nevertheless, since academic users tend to understand and comply with scholarly norms about citing and giving attribution, those new to data sharing should not be unduly alarmed about the statement illustrated above. (And DataShare provides a ‘suggested citation’ for every data item that helps the user comply with the attribution requirements.)

Since no overview of data and ethics would be complete without consideration given to confidentiality obligations of researchers towards their human subjects, I included a very short video clip from MANTRA, of Professor John MacInnes speaking about caring for data that contain personally identifying information or personal attributes.

For me the most challenging aspect of the roundtable and indeed the day, was the contribution by Dr Anouk Lang about working with data from social media. As an ethical researcher one cannot assume that consent is unnecessary when working with data streams (such as twitter) that are open to public viewing. For one thing, people may not expect views of their posts outside of their own circles – they treat it as a personal communication medium. For another they may assume that what they say is ethereal and will soon be forgotten and unavailable. A show of hands indicated only some of the audience had heard of the Twitter Developers and API, or Storify, which can capture tweets and other objects in a more permanent web page, illustrating her point.

While this whole area may be more common for social researchers – witness the Economic and Social Research Council’s funding of a Big Data Network over several years which includes social media data – Anouk’s work on digital culture proves Humanities researchers cannot escape “the plethora of ethics, privacy and risk issues surrounding the use (and reuse) of social media data.” (Communication on ESRC Big Data Network Phase 3.)

Robin Rice

Data Librarian