In collaboration with Scholarly Communications, the Data Library participated in the workshop “Data: photographs in research” as part of a series of workshops organised by Dr Tom Allbeson and Dr Ella Chmielewska for the pilot project “Fostering Photographic Research at CHSS” supported by the College of Humanities and Social Science (CHSS) Challenge Investment Fund.

In our research support roles, Theo Andrew and I addressed issues associated with finding and using photographs from repositories, archives and collections, and the challenges of re-using photographs in research publications. Workshop attendants came from a wide range of disciplines, and were at different stages in their research careers.

First, I gave a brief intro on terminology and research data basics, and navigated through media platforms and digital repositories like Jisc Media Hub, VADS, Wellcome Trust, Europeana, Live Art Archive, Flickr Commons, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Muybridge http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3a45870) – links below.

Then, Theo presented key concepts of copyright and licensing, which opened up an extensive discussion on what things researchers have to consider when re-using photographs and what institutional support researchers expect to have. Some workshop attendees shared their experience of reusing photographs from collections and archives, and discussed the challenges they face with online publications.

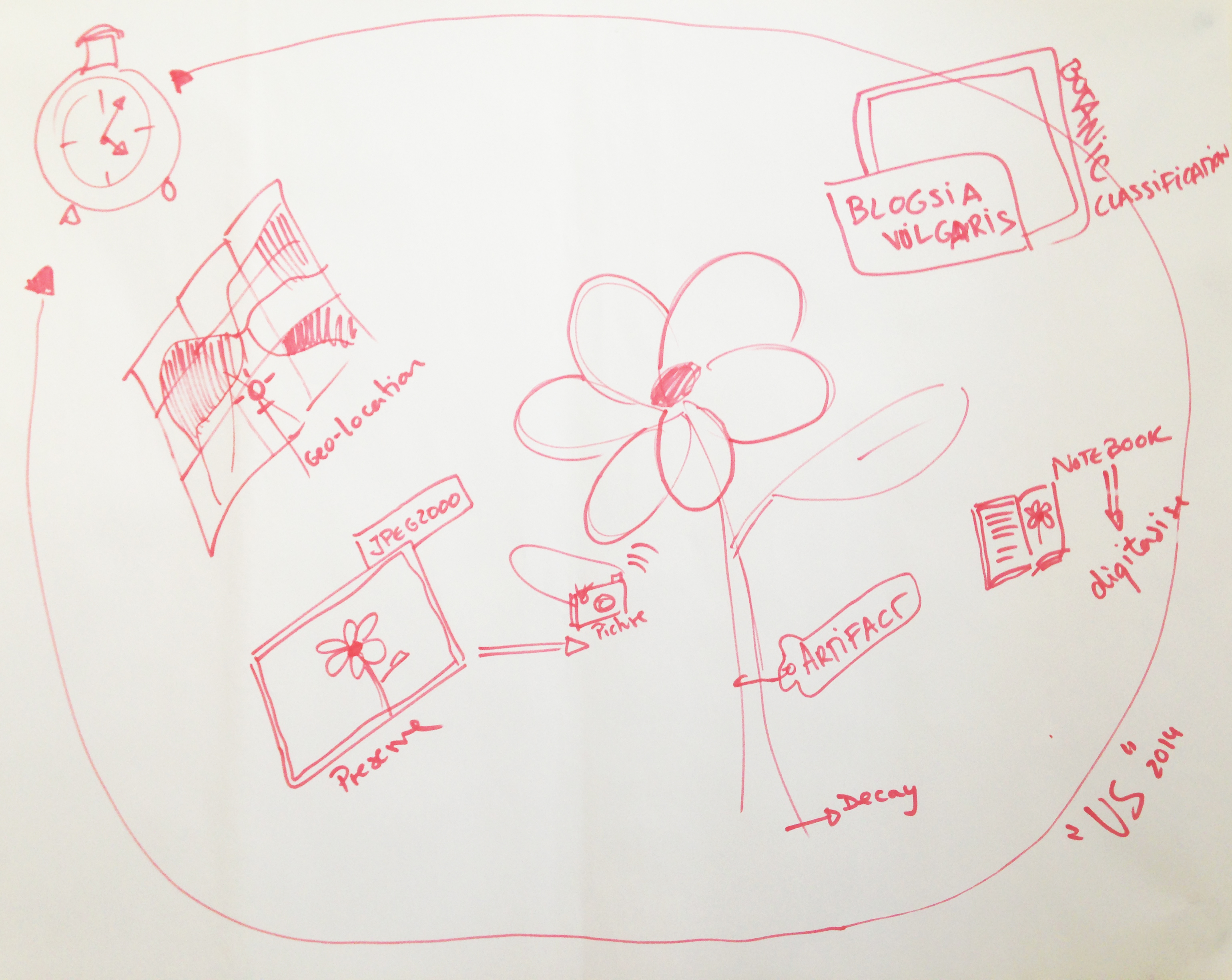

The last presentation tackling the basics of managing photographic research data was not delivered due to time constraints. The presentation was for researchers who produce photographic materials, however, advice on best RDM practice is relevant to any researcher independently of whether they are producing primary data or reusing secondary data. There may be another opportunity to present the remaining slides to CHSS researchers at a future workshop.

ONLINE RESOURCES

- Jisc Media Hub http://jiscmediahub.ac.uk/

- Visual Arts Data Service (VADS) http://www.vads.ac.uk/

- Wellcome Trust Image Collection http://wellcomeimages.org/

- British Library Catalogue of Photographs http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/photographs/

- Europeana http://europeana.eu/

- UK Data Service discover http://discover.ukdataservice.ac.uk/

- Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog http://www.loc.gov/pictures/

- Live Art Archive http://www.bris.ac.uk/theatrecollection/liveart/liveart_archivesmain.html

- Flickr Commons Project https://www.flickr.com/commons

LICENSING

- Intellectual Property Office (IPO) https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/305165/c-notice-201401.pdf

- Bern Convention http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/index.html

- WIPO Copyright Treaty http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/text.jsp?file_id=295166

- Copyright lengths: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries%27_copyright_lengths

- Creative Commons License http://creativecommons.org/

- Flickr (CC or Copyright)https://www.flickr.com/explore

- Wikimedia (CC) http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Photographs

- Wikimedia Licensing guide http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Licensing