I recently attended (13th May 2014) the one-day ‘Non-standard Research Outputs’ workshop at Nottingham Trent University.

[ 1 ] The day started with Prof Tony Kent and his introduction to some of the issues associated with managing and archiving non-text based research outputs. He posed the question: what uses do we expect these outcomes to have in the future? By trying to answer this question, we can think about the information that needs to be preserved with the output and how to preserve both, output and its documentation. He distinguished three common research outcomes in arts-humanities research contexts:

- Images. He showed us an image of a research output from a fashion design researcher. The issue with research outputs like this one is that they are not always self explanatory, and quite often open up the question of what is recorded in the image, and what the research outcome actually is. In this case, the image contained information about a new design for a heel of a shoe, but the research outcome itself, the heel, wasn’t easily identifiable, and without further explanation (description metadata), the record would be rendered unusable in the future.

- Videos. The example used to explain this type of non-text based research output was a video featuring some of the research of Helen Storey. The video contains information about the project Wonderland and how textiles dissolve in water and water bottles disintegrate. In the video, researchers explain how creativity and materials can be combined to address environmental issues. Videos like this one contain both, records of the research outcome in action (exhibition) and information about what the research outcome is and how the project ideas developed. These are very valuable outcomes, but they contain so much information that it’s difficult to untangle what is the outcome and what is information about the outcome.

- Statements. Drawing from his experience, he referred to researchers in fashion and performance arts to explain this research outcome, but I would say it applies to other researchers in humanities and artistic disciplines as well. The issue with these research outcomes is the complexity of the research problems the researchers are addressing and the difficulty of expressing and describing what their research is about, and how the different elements that compose their research project outcomes interact with each other. How much text do we need to understand non-text-based research outcomes such as images and videos? How important is the description of the overall project to understand the different research outcomes?

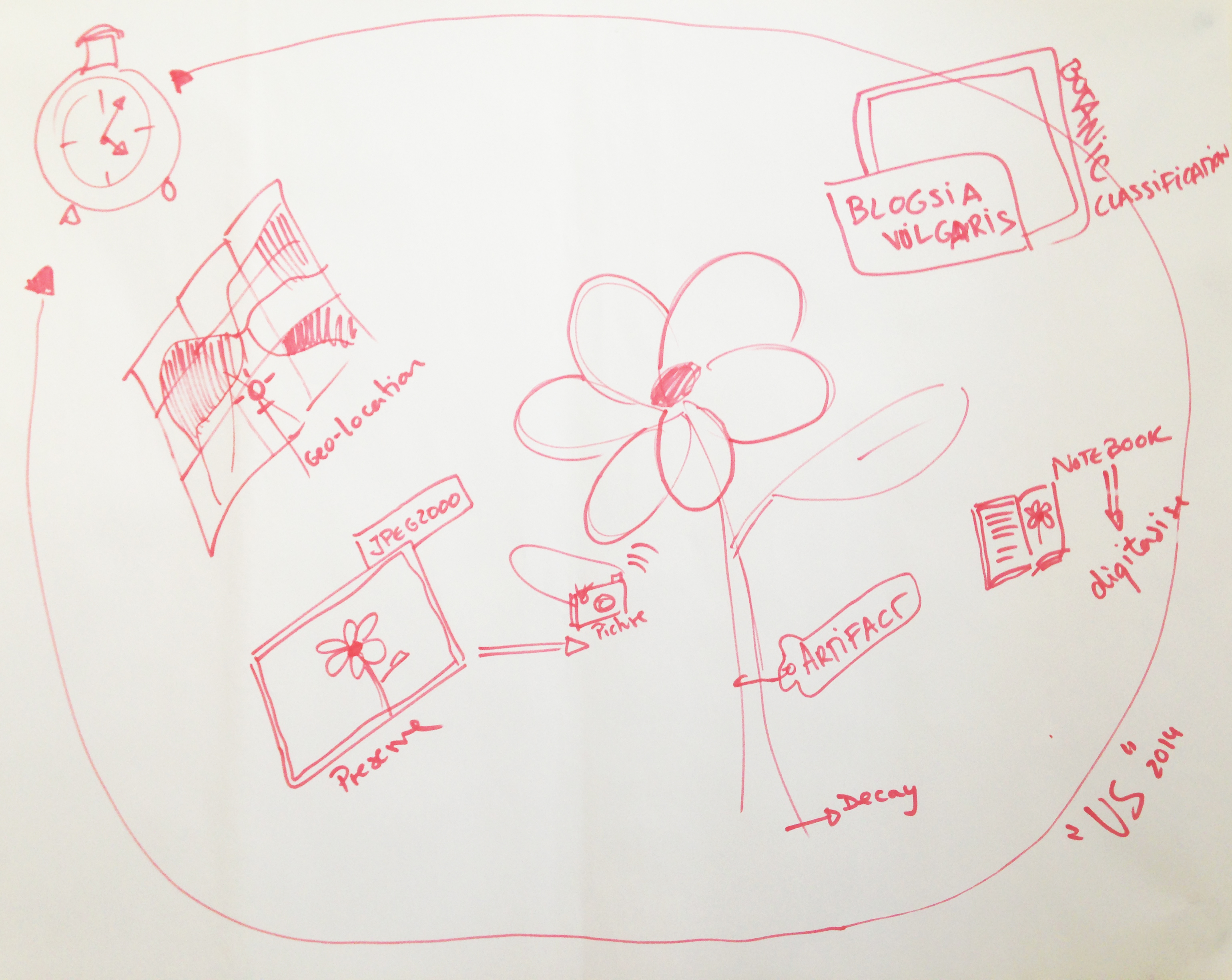

Other questions that come to mind when thinking about collecting and archiving non-standard research outputs such as exhibitions are: ‘what elements of the exhibition do we need to capture? Do we capture the pieces exhibited individually or collectively? How can audio/visual documentation convey the spatial arrangements of these pieces and their interrelations? What exactly constitutes the research outputs? Installation plans, cards, posters, dresses, objects, images, print-outs, visualisations, visitors comments, etc.? We also discussed how to structure data in a repository for artefacts that go into different exhibitions and installations. How to define a practice-based research output that has a life in its own? How do we address this temporal element, the progression and growth of the research output? This flowchart might be useful. Shared with permission of James Toon and collaborators.

Sketch from group discussion about artefacts and research practices that are ephemeral. How to capture the artefact as well as spatial information, notes, context, images, etc.

[ 2 ] After these first insights into the complexity of what non-standard research outcomes are, Stephanie Meece from the University of the Arts London (UAL) discussed her experience as institutional manager of the UAL repository. This repository is for research outputs, but they have also set up another repository for research data which is currently not publicly available. The research output repository has thousands of deposits, but the data repository has ingested only one dataset in its first two months of existence. The dataset in question is related to a media-archaeology research project where a number of analogue-based media (tapes) are being digitised. This reinforced my suspicion that researchers in the arts and humanities are ready and keen to deposit final research outputs, but are less inclined to deposit their core data, the primary sources from which their research outputs derive.

The UAL learned a great deal about non-standard research outputs through the KULTUR project, a Jisc funded project focused on developing repository solutions for the arts. Practice-based research methods engage with theories and practices in a different way than more traditional research methods. In their enquiries about specific metadata for the arts, the KULTUR project identified that metadata fields like ‘collaborators’ were mostly applicable to the arts (see metadata report, p. 25), and that this type of metadata fields differed from ‘data creator’ or ‘co-author.’ Drawing from this, we should certainly reconsider the metadata fields as well as the wording we use in our repositories to accommodate the needs of researchers in the arts.

Other examples of institutional repositories for the arts shown were VADS (University of the Creative Arts) and RADAR (Glasgow School of Art).

[ 3 ] Afterwards, Bekky Randall made a short presentation in which she explained that non-standard research outputs have a much wider variety of formats than standard text-based outputs. She also explained the importance of getting the researchers to do their own deposits, as they are the ones that know the information required for metadata fields. Once researchers find out what is involved in depositing their research, they will be more aware of what is needed, and get involved earlier with research data management (RDM). This might involve researchers depositing throughout the whole research project instead of at the end when they might have forgotten much of the information related to their files. Increasingly, research funders require data management plans, and there are tools to check what they expect researchers to do in terms of publication and sharing. See SHERPA for more information.

[ 4 ] The presentation slot after lunch is always challenging, but Prof Tom Fisher kept us awake with his insights into non-standard research outcomes. In the arts and humanities it’s sometimes difficult to separate insights from the data. He opened up the question of whether archiving research is mainly for Research Excellence Framework (REF) purposes. His point was to delve into the need to disseminate, access and reuse research outputs in the arts beyond REF. He argued that current artistic practice relates more to the present context (contemporary practice-based research) than to the past. In my opinion, arts and humanities always refer to their context but at the same time look back into the past, and are aware they cannot dismiss the presence of the past. For that reason, it seems relevant to archive current research outputs in the arts, because they will be the resources that arts and humanities researchers might want to use in the future.

He spent some time discussing the Journal for Artistic Research (JAR). This journal was designed taking into account the needs of artistic research (practice-based methodologies and research outcomes in a wide range of media), which do not lend themselves to the linearity of text-based research. The journal is peer-review and this process is made as transparent as possible by publishing the peer-reviews along with the article. Here is an example peer-review of an article submitted to JAR by ECA Professor Neil Mulholland.

[ 5 ] Terry Bucknell delivered a quick introduction to figshare. In his presentation he explained the origins of the figshare repository, and how the platform has improved its features to accommodate non-standard research outputs. The platform was originally thought for sharing scientific data, but has expanded its capabilities to appeal to all disciplines. If you have an ORCID account you can now connect it to figshare.

[ 6 ] The last presentation of the day was delivered by Martin Donnelly from the Digital Curation Centre (DCC) who gave a refreshing view into data management for the arts. He pointed out the issue of a scientifically-centred understanding of research data management, and that in order to reach the arts and humanities research community, we might need to change the wording, and change the word ‘data’ for ‘stuff’ when referring to creative research outputs. This reminded me of the paper ‘Making Sense: Talking Data Management with Researchers’ by Catharine Ward et al. (2011) and the Data Curation Profiles that Jane Furness, Academic Support Librarian, created after interviewing two researchers at Edinburgh College of Art, available here.

Quoting from his slides “RDM is the active management and appraisal of data over all the lifecycle of scholarly research.” In the past, data in the sciences was not curated or taken care of after the publication of articles; now this process has changed and most science researchers already actively manage their data throughout the research project. This could be extended to arts and humanities research. Why wait to do it at the end?

The main argument for RDM and data sharing is transparency. The data is available for scrutiny and replication of findings. Sharing is most important when events cannot be replicated, such as performance or a census survey. In the scientific context ‘data’ stands for evidence, but in the arts and humanities this does not apply in the same way. He then referred to the work of Leigh Garrett, and how data gets reused in the arts. Researchers in the arts reuse research outputs but there is the fear of fraud, because some people might not acknowledge the data sources from which their work derives. To avoid this, there is the tendency to have longer embargoes in humanities and arts than in sciences.

After Martin’s presentation, we called it a day. While, waiting for my train at Nottingham Station, I noticed I had forgotten my phone (and the flower sketch picture with it), but luckily Prof Tony Kent came to my rescue, and brought the phone to the station. Thanks to Tony and Off-Peak train tickets, I was able to travel back home on the day.

Rocio von Jungenfeld

Data Library Assistant