[First published on the DCC Blog, republished here with permission.]

Okay that title is a joke, but an apt one to name a brief reflection of this year’s International Digital Curation Conference in London this week, with the theme of looking ten years back and ten years forward since the UK Digital Curation Centre was founded.

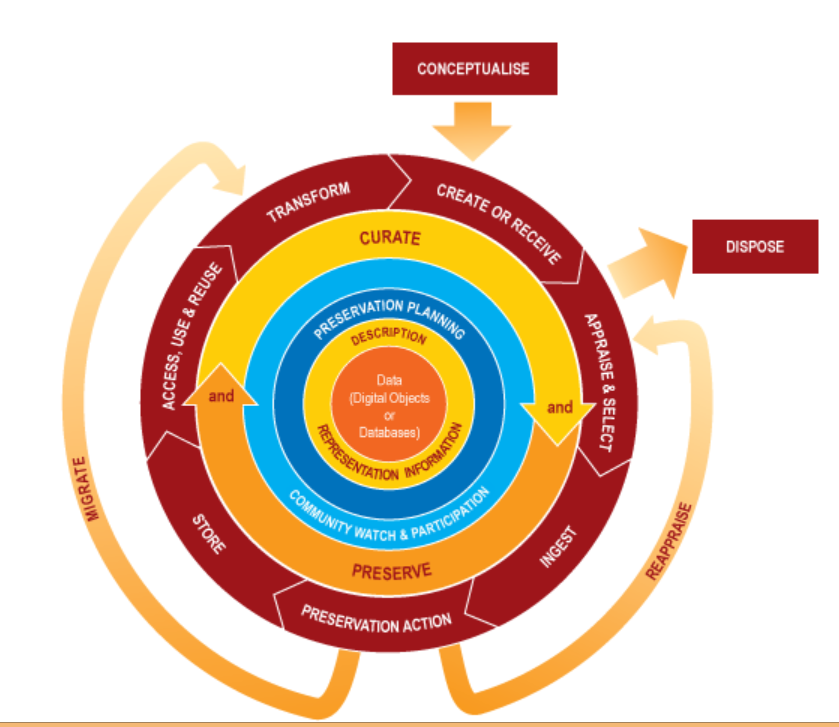

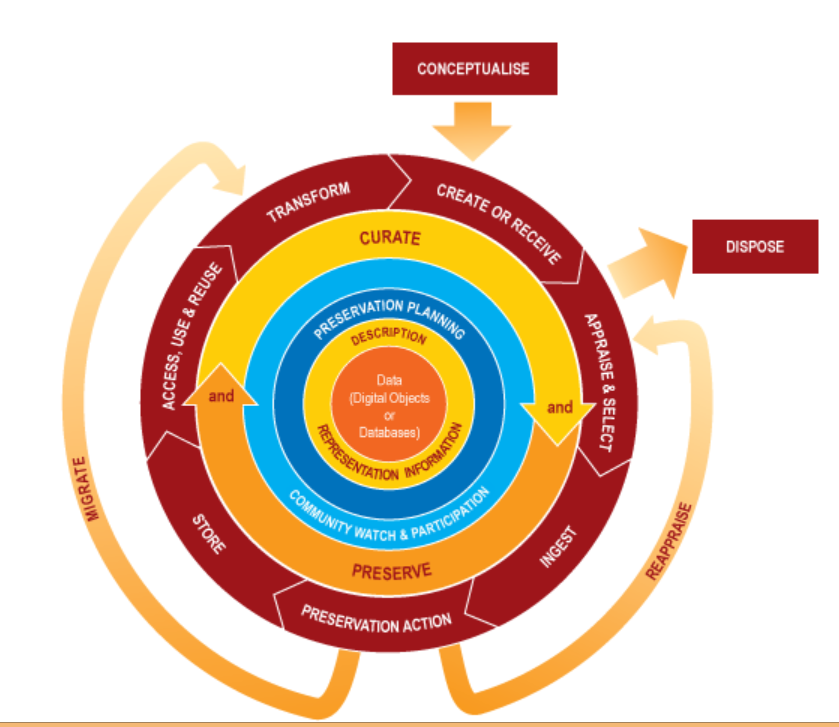

The joke references an alleged written or spoken mistake someone made in referring to the Digital Curation lifecycle model, gleefully repeated on the conference tweetstream (#idcc15). The model itself, as with all great reference works, both builds on prior work and was a product of its time – helping to add to the DCC’s authority within and beyond the UK where people were casting about for common language and understanding in this new terrain of digital preservation, data curation, and – a perplexing combination of terms which perhaps still hasn’t quite taken off, ‘digital curation’ (at least not to the same extent as ‘research data management’). I still have my mouse-mat of the model and live with regrets it was never made into a frisbee.

The Digital Curation Lifecycle Model, Sarah Higgins & DCC, 2008

They say about Woodstock that ‘if you remember it you weren’t really there’, so I don’t feel too bad that it took Tony Hey’s coherent opening plenary talk to remind me of where we started way back in 2004 when a small band under the directorship of Peter Burnhill (services) and Peter Buneman (research) set up the DCC with generous funding from Jisc and EPSRC. Former director Chris Rusbridge likes to talk about ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’ when describing long-term preservation, and Tony reminded us of the important, immediate predecessors of the UK e-Science Programme and the ground-breaking government investment in the Australian National Data Service (ANDS) that was already changing a lot of people’s lifestyles, behaviours and outlooks.

Traditionally the conference has a unique format that focuses on invited panels and talks on the first day, with peer-reviewed research and practice papers on the second, interspersed with demos and posters of cutting edge projects, followed by workshops in the same week. So whilst I always welcome the erudite words of the first day’s contributors, at times there can be a sense of, ‘Wait – haven’t things moved on from there already?’ So it was with the protracted focus on academic libraries and the rallying cries of the need for them to rise to the ‘new’ challenges during the first panel session chaired by Edinburgh’s Geoffrey Boulton, focused ostensibly on international comparisons. Librarians – making up only part of the diverse audience – were asking each other during the break and on twitter, isn’t that exactly what they have been doing in recent years, since for example, the NSF requirements in the States and the RCUK and especially EPSRC rules in the UK, for data management planning and data sharing? Certainly the education and skills of data curators as taught in iSchools (formerly Library Schools) has been a mainstay of IDCC topics in recent years, this one being no exception.

But has anything really changed significantly, either in libraries or more importantly across academia since digital curation entered the namespace a decade ago? This was the focus of a panel led by the proudly impatient Carly Strasser, who has no time for ‘slow’ culture change, and provocatively assumes ‘we’ must be doing something wrong. She may be right, but the panel was divided. Tim DiLauro observed that some disciplines are going fast and some are going slow – depending on whether technology is helping them get the business of research done. And even within disciplines there are vast differences –-perhaps proving the adage that ‘the future is here, it’s just not distributed yet’.

Carly Strasser’s Panel Session, IDCC15

Geoffrey Bilder spoke of tipping points by looking at how recently DOIs (Digital Object Identifiers, used in journal publishing) meant nothing to researchers and how they have since caught on like wildfire. He also pointed blame at the funding system which focuses on short-term projects and forces researchers to disguise their research bids as infrastructure bids – something they rightly don’t care that much about in itself. My own view is that we’re lacking a killer app, probably because it’s not easy to make sustainable and robust digital curation activity affordable and time-rewarding, never mind profitable. (Tim almost said this with his comparison of smartphone adoption). Only time will tell if one of the conference sponsors proves me wrong with its preservation product for institutions, Rosetta.

It took long-time friend of the DCC Clifford Lynch to remind us in the closing summary (day 1) of exactly where it was we wanted to get to, a world of useful, accessible and reproducible research that is efficiently solving humanity’s problems (not his words). Echoing Carly’s question, he admitted bafflement that big changes in scholarly communication always seem to be another five years away, deducing that perhaps the changes won’t be coming from the publishers after all. As ever, he shone a light on sticking points, such as the orthogonal push for human subject data protection, calling for ‘nuanced conversations at scale’ to resolve issues of data availability and access to such datasets.

Perhaps the UK and Scotland in particular are ahead in driving such conversations forward; researchers at the University of Edinburgh co-authored a report two years ago for the government on “Public Acceptability of Data Sharing Between the Public, Private and Third Sectors for Research Purposes,” as a pre-cursor to innovations in providing researchers with secure access to individual National Health Service records linked to other forms of administrative data when informed consent is not possible to achieve.

Given the weight of this societal and moral barrier to data sharing, and the spread of topics over the last 10 years of conferences, I quite agree with Laurence Horton, one of the panelists, who said that the DCC should give a particular focus to the Social Sciences at next year’s conference.

Robin Rice

Data Librarian (and former Project Coordinator, DCC)

University of Edinburgh