Lorna M. Campbell, a Digital Education Manager with EDINA and the University of Edinburgh, writes about the ideas shared and discussed at the open.ed event this week.

Earlier this week I was invited by Ewan Klein and Melissa Highton to speak at Open.Ed, an event focused on Open Knowledge at the University of Edinburgh. A storify of the event is available here: Open.Ed – Open Knowledge at the University of Edinburgh.

“Open Knowledge encompasses a range of concepts and activities, including open educational resources, open science, open access, open data, open design, open governance and open development.”

– Ewan Klein

Ewan set the benchmark for the day by reminding us that open data is only open by virtue of having an open licence such as CC0, CC BY, CC SA. CC Non Commercial should not be regarded as an open licence as it restricts use. Melissa expanded on this theme, suggesting that there must be an element of rigour around definitions of openness and the use of open licences. There is a reputational risk to the institution if we’re vague about copyright and not clear about what we mean by open. Melissa also reminded us not to forget open education in discussions about open knowledge, open data and open access. Edinburgh has a long tradition of openness, as evidenced by the Edinburgh Settlement, but we need a strong institutional vision for OER, backed up by developments such as the Scottish Open Education Declaration.

I followed Melissa, providing a very brief introduction to Open Scotland and the Scottish Open Education Declaration, before changing tack to talk about open access to cultural heritage data and its value to open education. This isn’t a topic I usually talk about, but with a background in archaeology and an active interest in digital humanities and historical research, it’s an area that’s very close to my heart. As a short case study I used the example of Edinburgh University’s excavations at Loch na Berie broch on the Isle of Lewis, which I worked on in the late 1980s. Although the site has been extensively published, it’s not immediately obvious how to access the excavation archive. I’m sure it’s preserved somewhere, possibly within the university, perhaps at RCAHMS, or maybe at the National Museum of Scotland. Where ever it is, it’s not openly available, which is a shame, because if I was teaching a course on the North Atlantic Iron Age there is some data form the excavation that I might want to share with students. This is no reflection on the directors of the fieldwork project, it’s just one small example of how greater access to cultural heritage data would benefit open education. I also flagged up a rather frightening blog post, Dennis the Paywall Menace Stalks the Archives, by Andrew Prescott which highlights the dangers of what can happen if we do not openly licence archival and cultural heritage data – it becomes locked behind commercial paywalls. However there are some excellent examples of open practice in the cultural heritage sector, such as the National Portrait Gallery’s clearly licensed digital collections and the work of the British Library Labs. However openness comes at a cost and we need to make greater efforts to explore new business and funding models to ensure that our digital cultural heritage is openly available to us all.

Ally Crockford, Wikimedian in Residence at the National Library of Scotland, spoke about the hugely successful Women, Science and Scottish History editathon recently held at the university. However she noted that as members of the university we are in a privileged position in that enables us to use non-open resources (books, journal articles, databases, artefacts) to create open knowledge. Furthermore, with Wikpedia’s push to cite published references, there is a danger of replicating existing knowledge hierarchies. Ally reminded us that as part of the educated elite, we have a responsibility to open our mindsets to all modes of knowledge creation. Publishing in Wikipedia also provides an opportunity to reimagine feedback in teaching and learning. Feedback should be an open participatory process, and what better way for students to learn this than from editing Wikipedia.

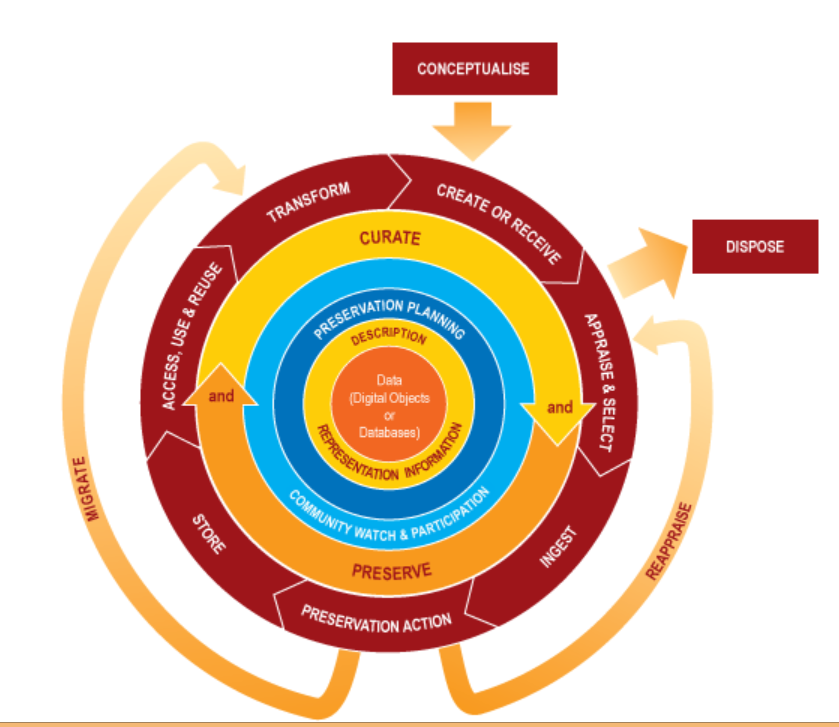

Robin Rice, of EDINA & Data Library, asked the question what does Open Access and Open Data sharing look like? Open Access publications are increasingly becoming the norm, but we’re not quite there yet with open data. It’s not clear if researchers will be cited if they make their data openly available and career rewards are uncertain. However there are huge benefits to opening access to data and citizen science initiatives; public engagement, crowd funding, data gathering and cleaning, and informed citizenry. In addition, social media can play an important role in working openly and transparently.

James Bednar, talking about computational neuroscience and the problem of reproducibility, picked up this theme, adding that accountability is a big attraction of open data sharing. James recommended using iPython Notebook for recording and sharing data and computational results and helping to make them reproducible. This promoted Anne-Marie Scott to comment on twitter:

Very cool indeed.

James Stewart spoke about the benefits of crowdsourcing and citizen science. Despite the buzz words, this is not a new idea, there’s a long tradition of citizens engaging in science. Darwin regularly received reports and data from amateur scientists. Maintaining transparency and openness is currently a big problem for science, but openness and citizen science can help to build trust and quality. James also cited Open Street Map as a good example of building community around crowdsourcing data and citizen science. Crowdsourcing initiatives create a deep sense of community – it’s not just about the science, it’s also about engagement.

After coffee (accompanied by Tunnocks caramel wafers – I approve!) We had a series of presentations on the student experience and students engagement with open knowledge.

Paul Johnson and Greg Tyler, from the Web, Graphics and Interaction section of IS, spoke about the necessity of being more open and transparent with institutional data and the importance of providing more open data to encourage students to innovate. Hayden Bell highlighted the importance of having institutional open data directories and urged us to spend less time gathering data and more making something useful from it. Students are the source of authentic experience about being a student – we should use this! Student data hacks are great, but they often have to spend longer getting and parsing the data than doing interesting stuff with it. Steph Hay also spoke about the potential of opening up student data. VLEs inform the student experience; how can we open up this data and engage with students using their own data? Anonymised data from Learn was provided at Smart Data Hack 2015 but students chose not to use it, though it is not clear why. Finally, Hans Christian Gregersen brought the day to a close with a presentation of Book.ed, one of the winning entries of the Smart Data Hack. Book.ed is an app that uses open data to allow students to book rooms and facilities around the university.

What really struck me about Open.Ed was the breadth of vision and the wide range of open knowledge initiatives scattered across the university. The value of events like this is that they help to share this vision with fellow colleagues as that’s when the cross fertilisation of ideas really starts to take place.

This report first appeared on Lorna M. Campbell’s blog, Open World: lornamcampbell.wordpress.com/2015/03/11/open-ed

P.S. another interesting talk came from Bert Remijsen, who spoke of the benefits he has found from publishing his linguistics research data using DataShare, particularly the ability to enable others to hear recordings of the sounds, words and songs described in his research papers, spoken and sung by the native speakers of Shilluk, with whom he works during his field research in South Sudan.