On 4th June 2025, we held the 4th annual Edinburgh Open Research Conference. The conference welcomed anyone who is part of a research community, from researchers and technicians to support services and curious citizens. This year almost 300 people joined us from around the world to discuss challenges, success stories, and next steps to further open research.

Attendees chatting. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

This year’s theme was “What’s stopping us?” and centred around barriers to making progress in Open Research. We had a full-on bill of events, with 18 speakers presenting their work and ideas throughout the day. We were honoured to host many speakers who had travelled to attend the conference, especially those who travelled from as far as India and the USA. In case you couldn’t join us, all sessions were recorded – you can find the videos on our Media Hopper:

https://media.ed.ac.uk/channel/Edinburgh+Open+Research/259602172

And you’ll find the proceedings from this year’s conference here:

https://journals.ed.ac.uk/eor/issue/view/696

Session 1: Communities and collaborations

In the first session we heard about different methods for understanding the barriers to adopting open research (Ailsa Niven and Zuzanna Zagrodska). I was particularly interested in Zuzanna’s finding that people become less enthusiastic about Open Research with more experience as a researcher. We also heard about some personal experiences of engaging with Open Research. Judith Fathallah spoke about how Open Access publishing models centre author agency, while Fiona Ramage talked about putting her career on the line to stand up for academic integrity.

Zuzanna Zagrodzka. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

Judith Fathallah. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

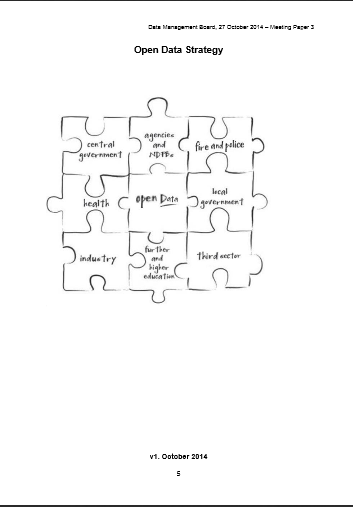

Session 2: Policy and Procedures

In the second session we heard lightning talks on how the Diamond Open Access model can help early career researchers (Varina Jones-Reid and Sarah Sharp), applying FAIR data principles to institutional data (Damon Querry), and whether open research mandates work in the context of the 2021 REF Open Access Policy (Ali Kay). The final talk was on the Research Culture Action plan at Edinburgh and how Research Culture and Open Research intersect (Crispin Jordan and Will Cawthorn).

Ali Kay. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

Crispin Jordan. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

Lunch: Research Cafe / Networking

During the lunch break, we had the opportunity to gather and network or to attend this month’s Research Cafe event, held monthly by our wonderful Academic Support Librarians. Ruthanne Baxter, Civic Engagement Manager for our Heritage Collections, joined us to talk about prescribing heritage-based social support programs as a non-clinical health intervention for students and Edinburgh locals.

Ruthanne Baxter. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

Session 3: Systems and Infrastructure

After lunch, a couple of speakers talked about open-source software, one for automating lab work and for divesting from Big Tech corporations whose values are not aligned with our own. We also heard about new tools aimed at solving specific obstacles to Open Access – one tool for helping researchers identify and overcome barriers to sharing qualitative research data, and a new platform to make publication in neuroscience more accessible using preprint peer-review. I liked that the speakers in this session provided practical solutions and tools.

Mahesh Karnani. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

Audience member listening. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

Session 4: Knowledge, Skills & Training

During the final session, speakers discussed Open Research in a global context: Milena Dobreva shared her reflections on her knowledge exchange in Bulgaria, and our old friend Tapas Kumar Mohanty talked about building a culture of Open Science in a Global South context through the NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Respiratory Health (RESPIRE) project. We also heard about new training-related innovations. Louise Saul discussed reward and recognition for research-enabling staff who provide Open Research training, and Camilla Elphick presented a new interactive and accessible Open Research learning resource she co-developed at the Open University.

Milena Dobreva. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

Tapas Kumar Mohanty. Photo by Eugen Stoica.

For me, the day highlighted the benefits of including a patchwork of voices in discussions around open research. Hearing personal stories and case studies alongside quantitative methods and formal analysis provided great insight into the state of Open Research now, the obstacles different research communities face, and ways we can enable people to embrace more open research practices. I left the day with a much clearer picture of where we are along the path of progress and where we should go next.

Thank you to all our speakers, our staff volunteers, and everyone who attended. A huge thanks to Kerry Miller and Nel Coleman, who pulled it all off without a hitch!

You can find all this year’s sessions as videos on MediaHopper: https://media.ed.ac.uk/channel/Edinburgh+Open+Research/259602172

To read more about Edinburgh Open Research and sign up for the newsletter, where we’ll notify you about future events: https://library.ed.ac.uk/research-support/open-research

To read more about Edinburgh ReproducibiliTea and Open Research Initiative: https://library.ed.ac.uk/research-support/open-research/reproducibilitea-eori

Evelyn Williams

Research Data Support Assistant

Research Data Service