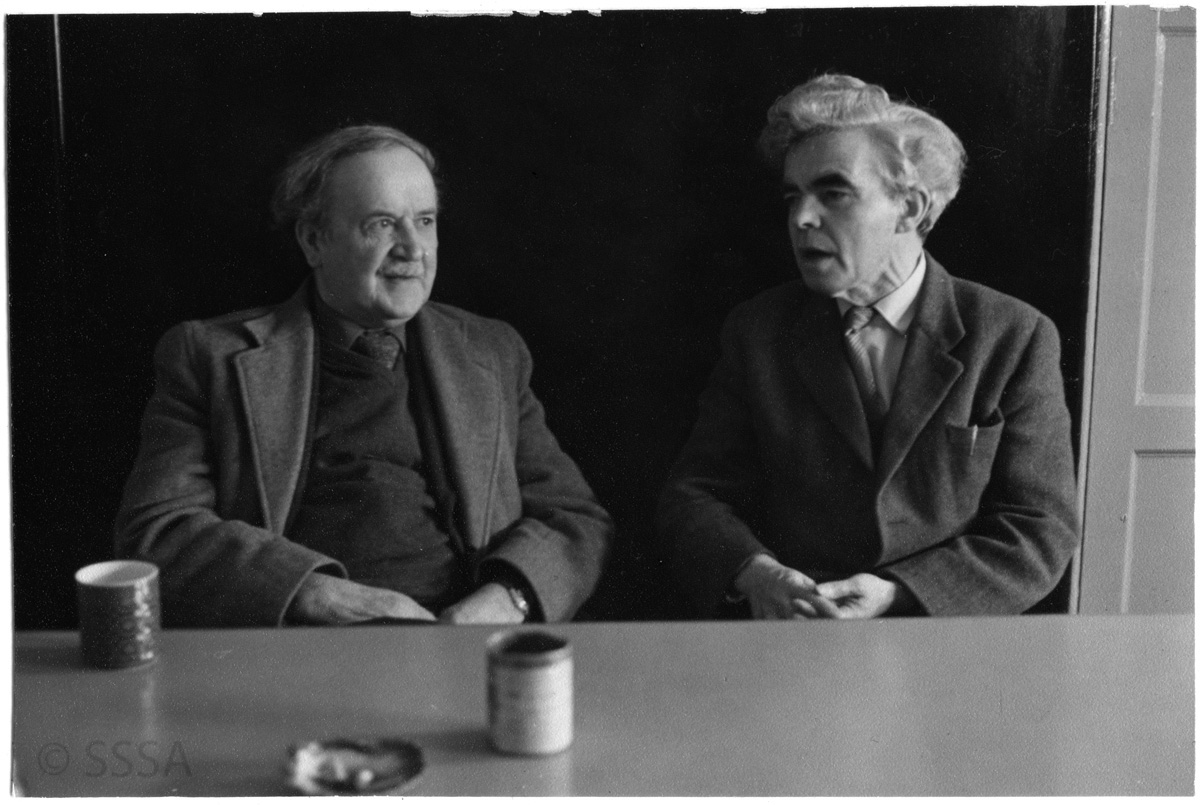

“Too Principled, Too Honest”

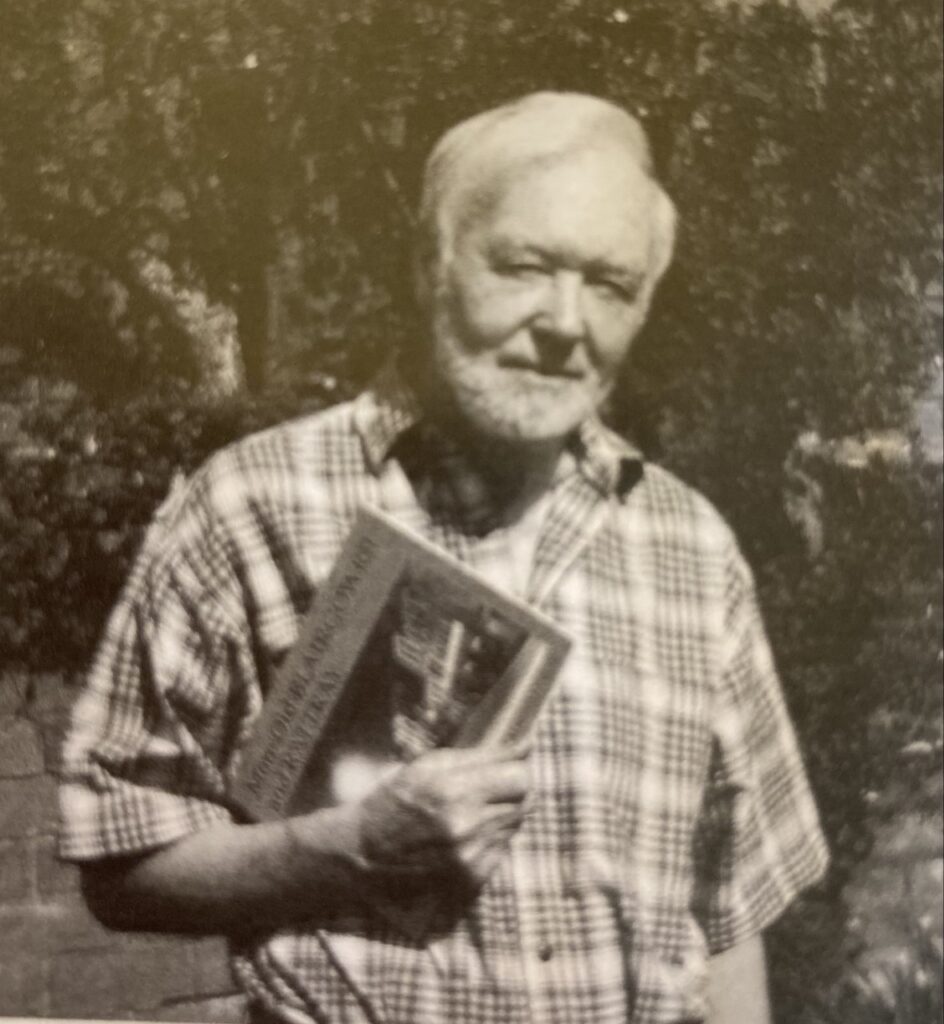

Thomas Ferguson Rodger, Professor of Psychological Medicine

Response by: Dr Sarah Phelan

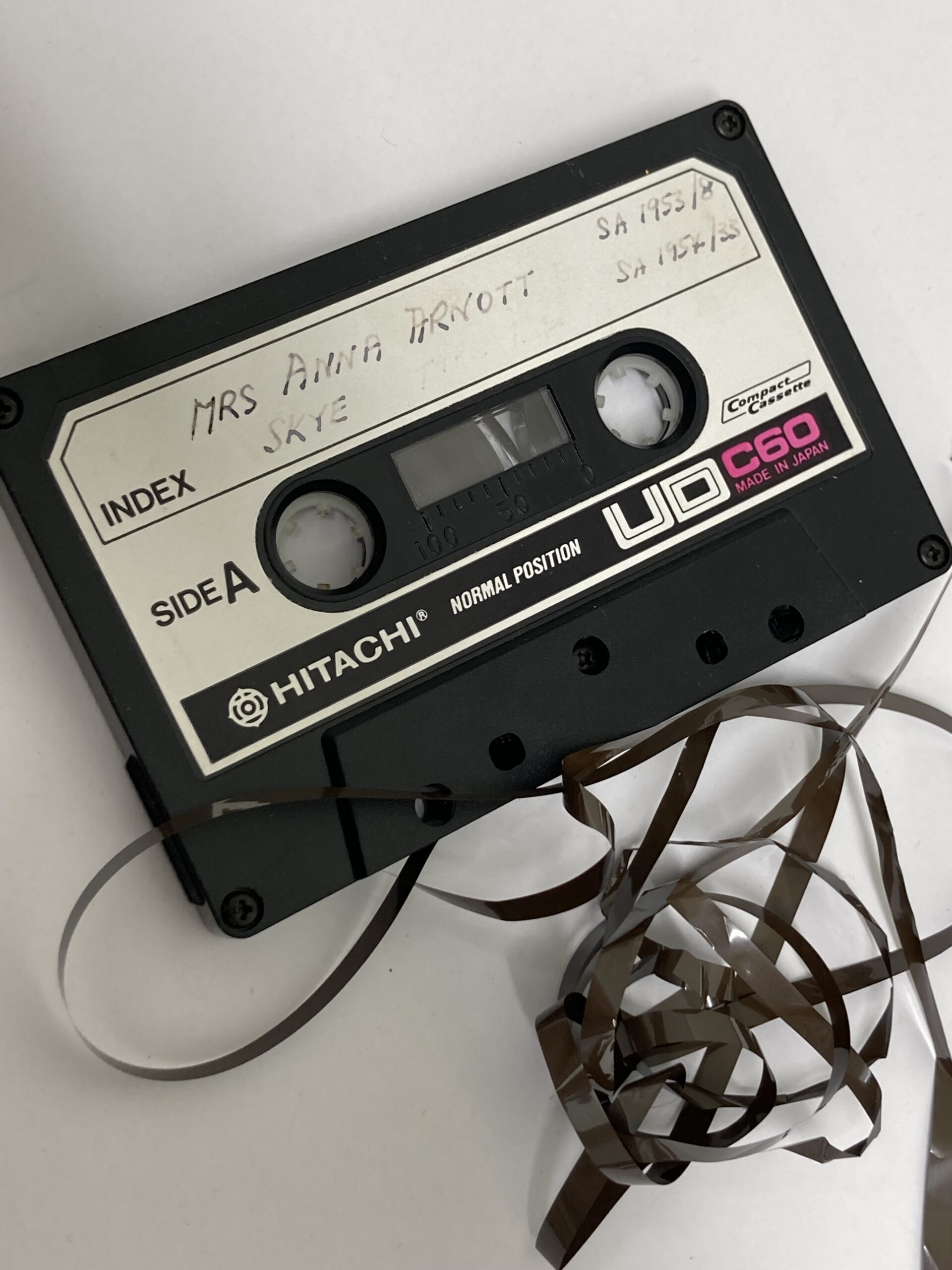

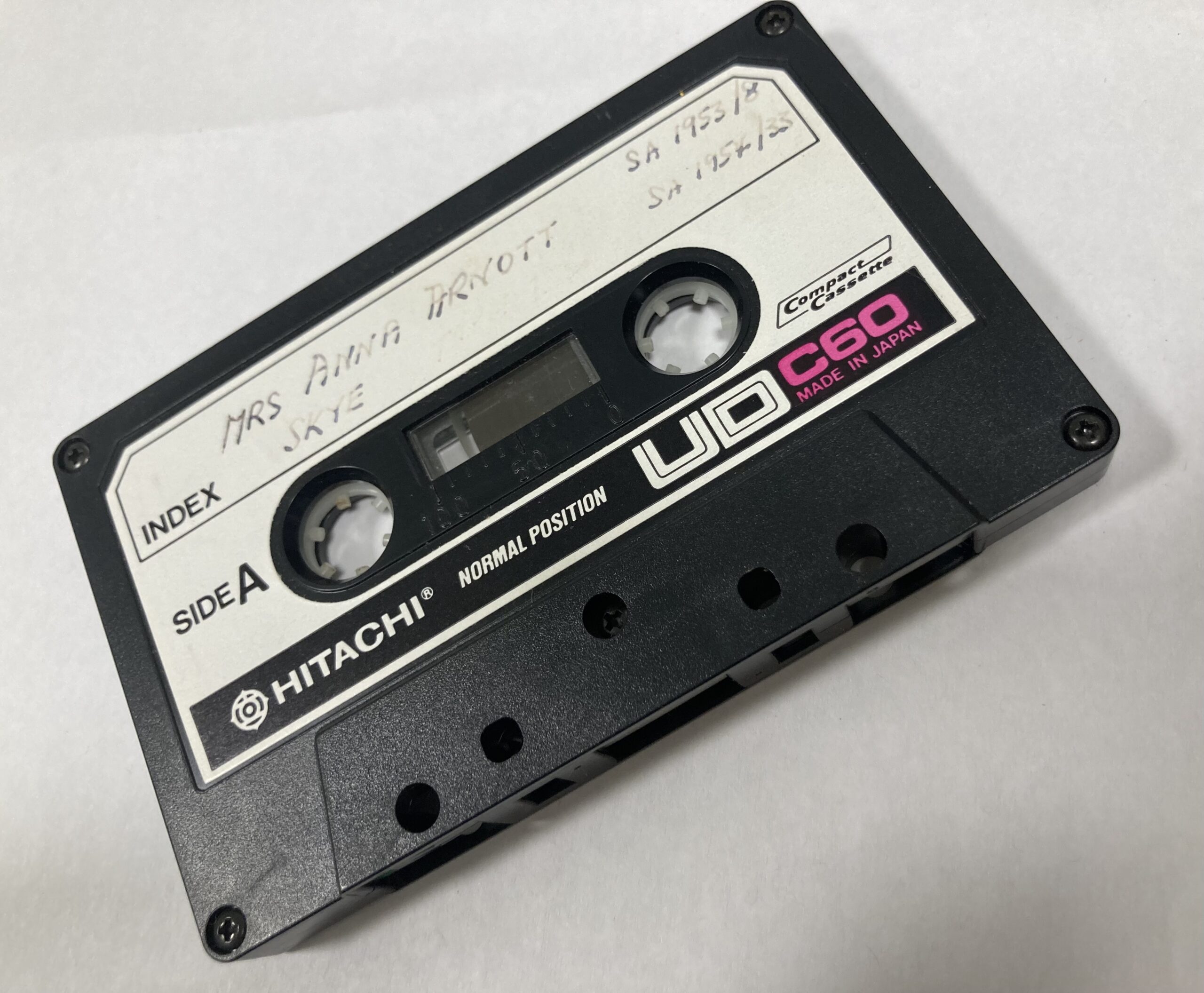

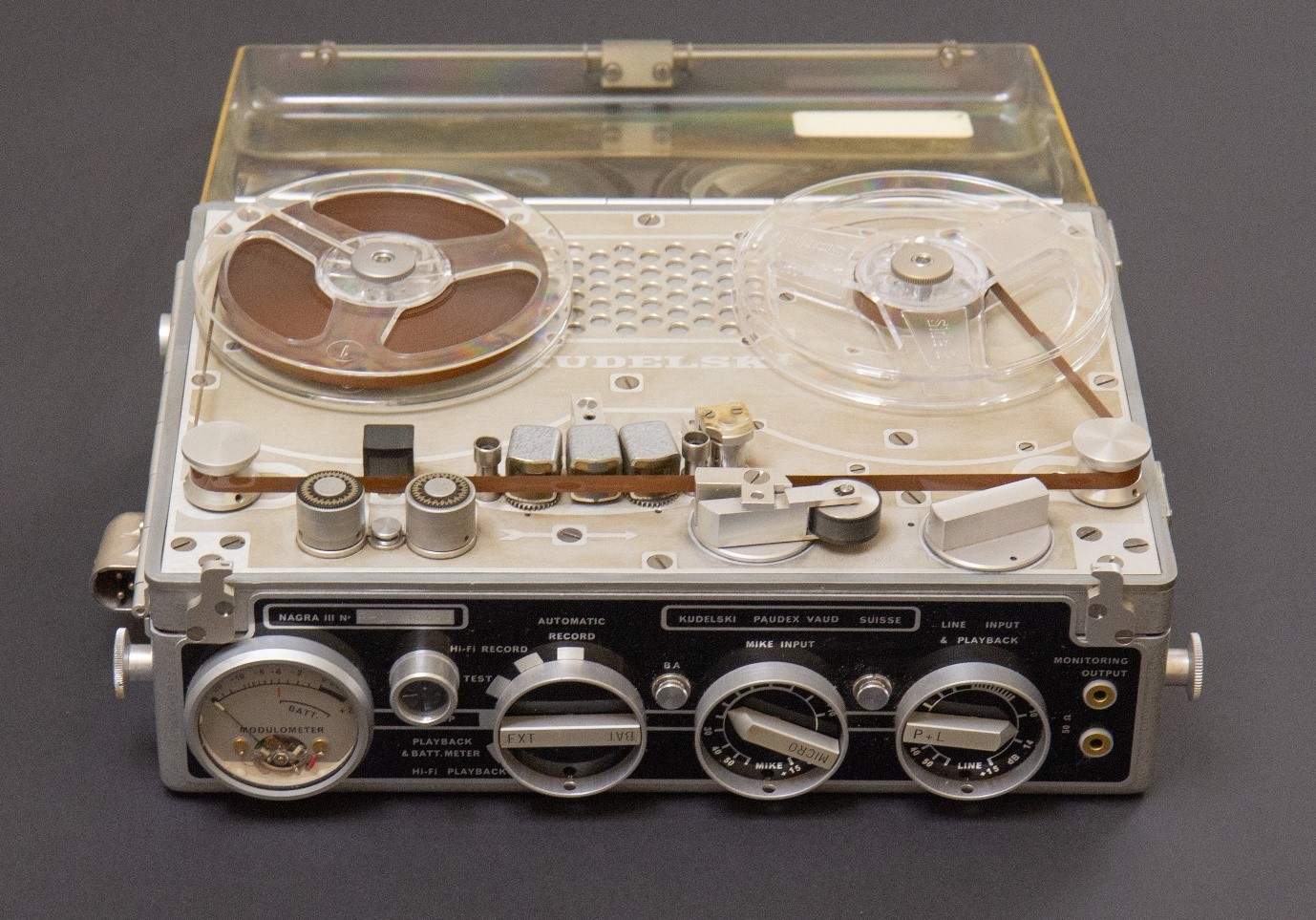

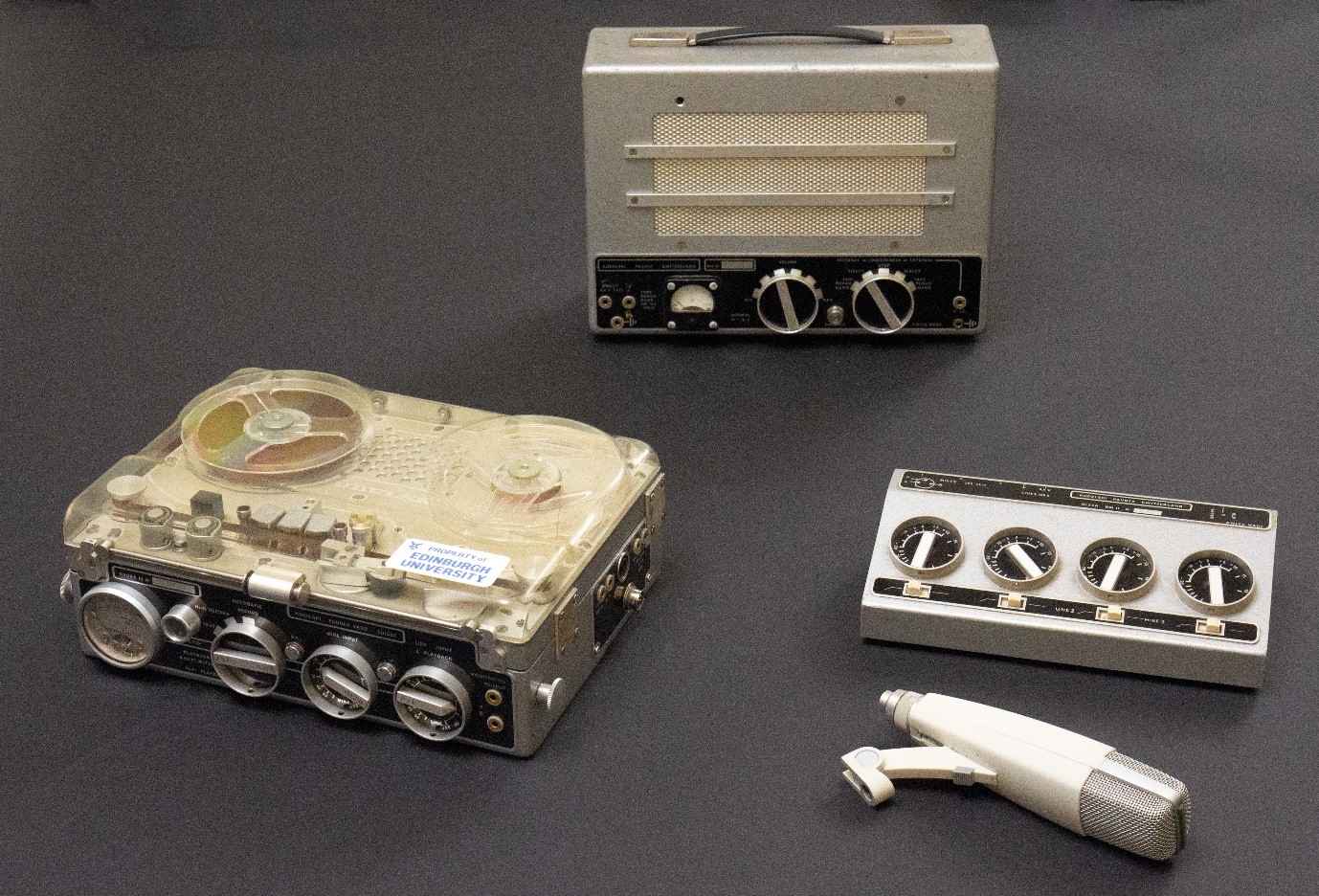

Recording: Interviews relating to Thomas Ferguson Rodger (1907-1978), interviewed by Sarah Phelan, Various dates (School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh)

Contributor: Dr Sarah Phelan

Professor Rodger giving his lecture ‘Some Observations on Mental Health Services in Scotland under the National Health Services Act’ to the Medical Institute of Kiev, 1955.

Image Credit: University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections: MS Morgan H/1/2.

I have chosen to respond to my own contribution to the School of Scottish Studies Archive: a series of oral history interviews relating to the Glasgow-based psychiatrist, Thomas Ferguson Rodger (1907-1978). Thomas Ferguson Rodger was first Professor of Psychological Medicine at the University of Glasgow (1948-72) and a consultant psychiatrist at several Glasgow hospitals. I conducted these interviews with Rodger’s family and former colleagues as part of a PhD on Rodger’s contribution to twentieth-century psychiatry which was undertaken at the Medical Humanities Research Centre at the University of Glasgow and completed in 2018. Upon being awarded my PhD, I submitted the audio recordings and transcripts of these interviews to the School of Scottish Studies Sound Archive, grateful that my interviewees’ recollections would be carefully preserved and rendered accessible for researchers.

Rodger, known as Fergus to family and friends, was born in Glasgow on 4 November 1907[1] to Thomas and Ellen (nee Allan) Rodger.[2] Rodger had three brothers: William, James and Alan, and the family lived in Glasgow’s West End area.[3]

Upon being awarded a BSc in 1927 and an MB ChB in 1929 from the University of Glasgow,[4] Rodger worked as ‘assistant to Sir David Henderson, at Glasgow Royal Mental Hospital’.[5] Concurrently, he was awarded a Diploma of Psychological Medicine (D.P.M.) from the University of London in April 1931.[6] He then worked under the ‘most influential teacher of psychiatry, Professor Adolph Meyer at the Johns Hopkins University Baltimore’. Between 1933 and 1940, Rodger was again employed at Gartnavel, now as Deputy Superintendent, and also as an Assistant Lecturer in Psychiatry at the University of Glasgow.[7] Working as a military psychiatrist in the Second World War, Rodger was promoted to the ‘rank of Brigadier’ and made important contributions to personnel selection methods.

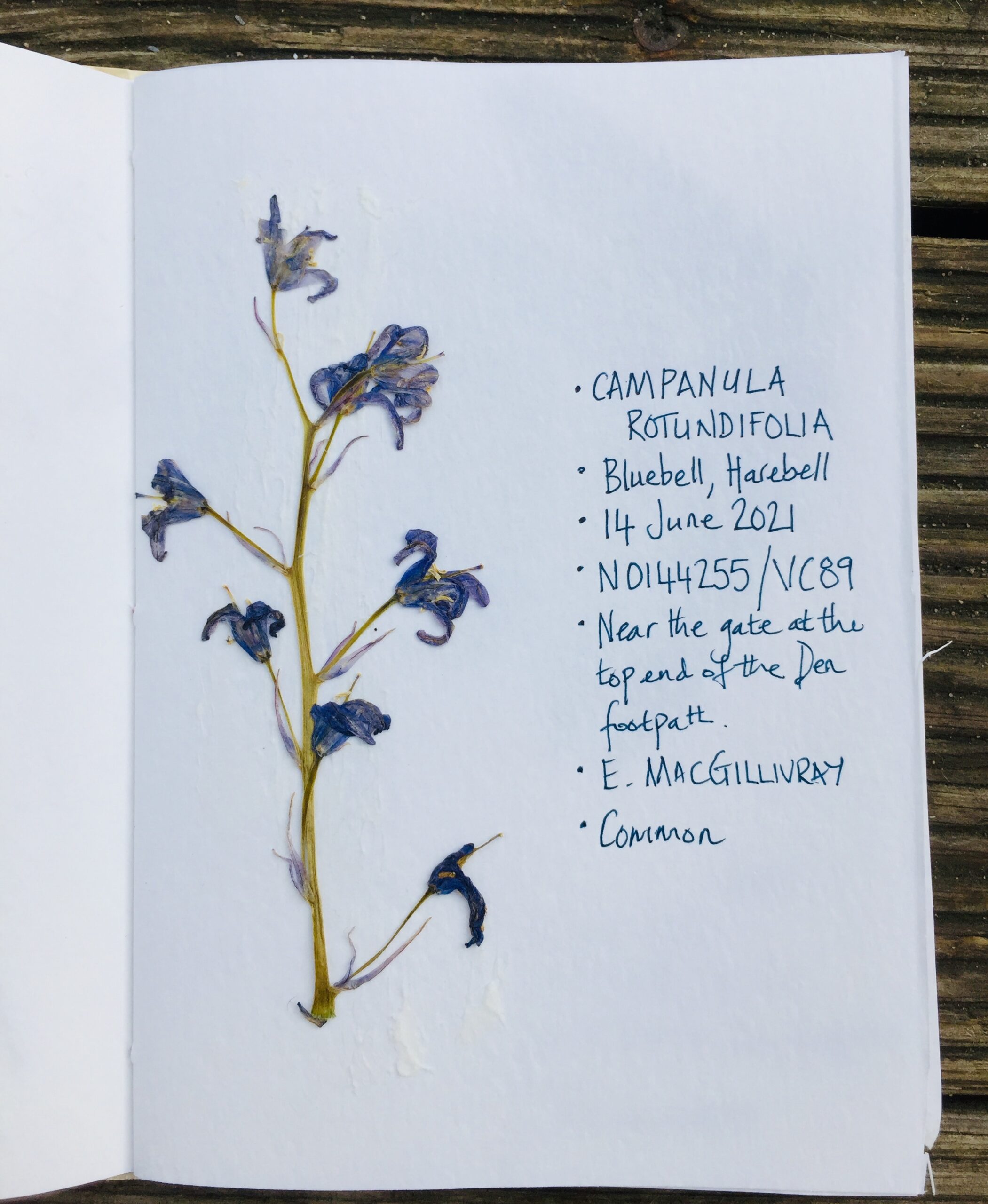

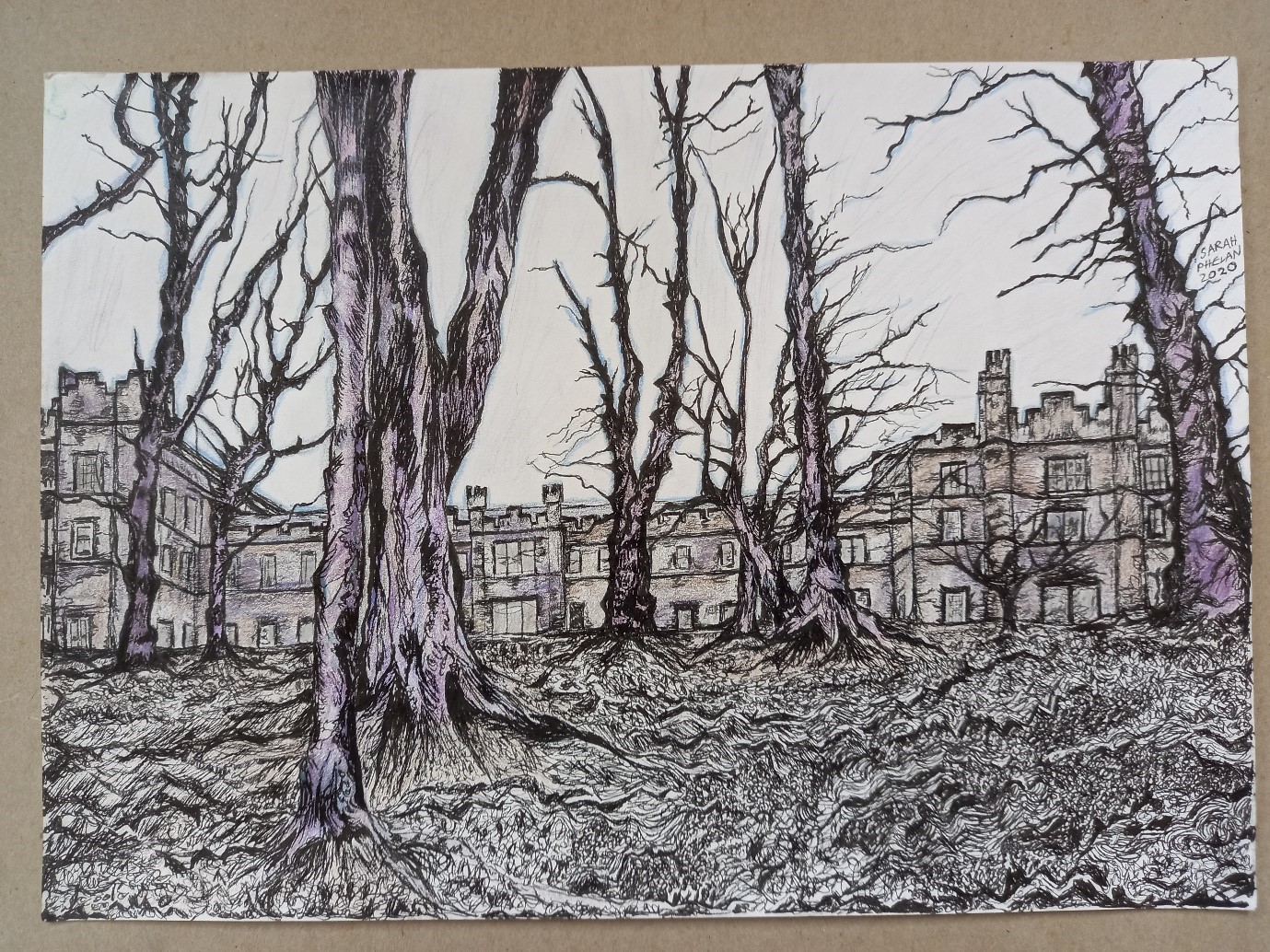

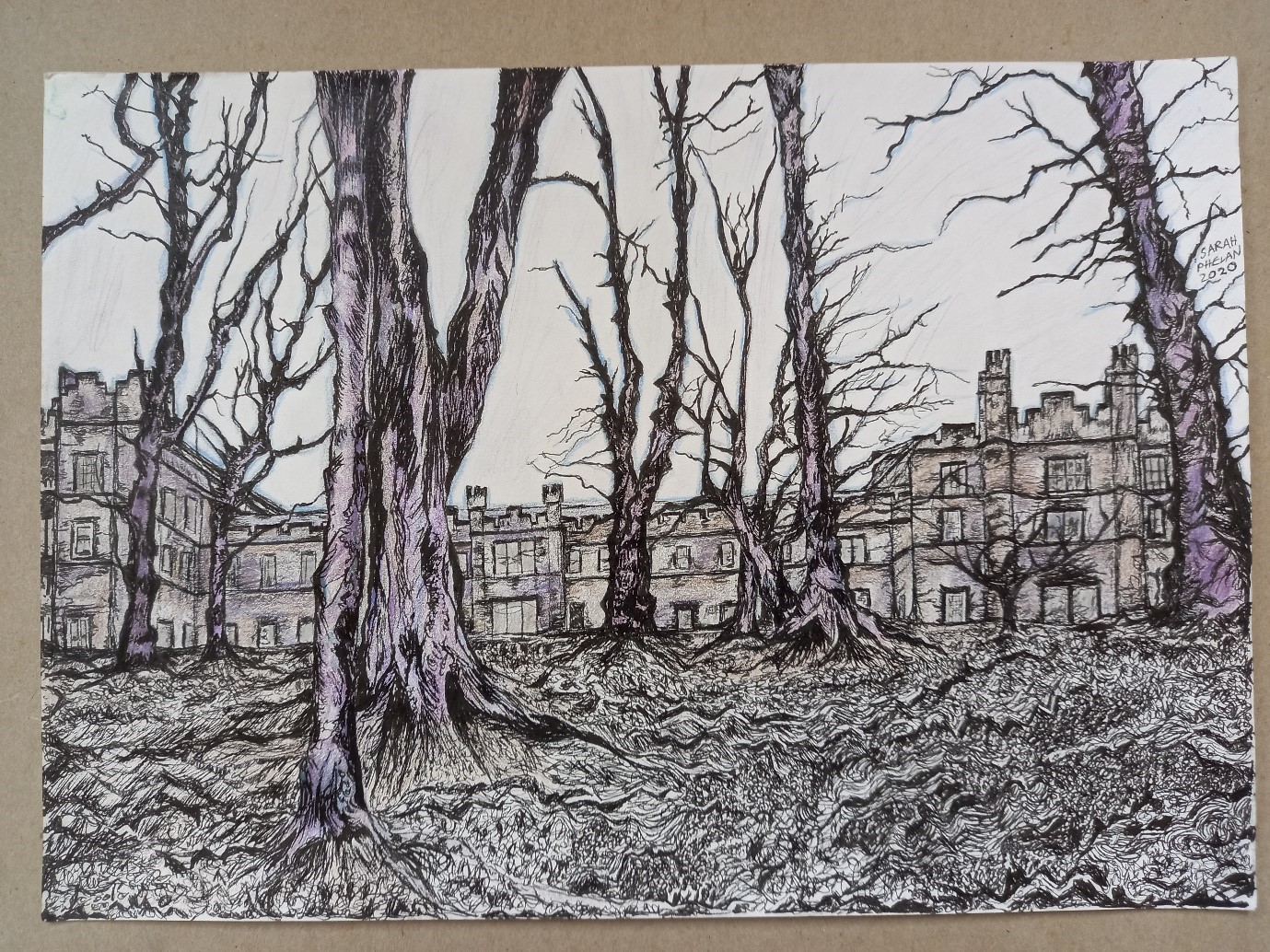

Sarah Phelan, Trees of Gartnavel, 2020.

Image Copyright: Sarah Phelan

After the war, Rodger took up a position as Senior Commissioner on the General Board of Control for Scotland until 1948, when he was offered the professorship in psychological medicine. He established his department at the Southern General Hospital. During this time, he also fulfilled many prominent positions in official bodies, both domestic and further afield. He received a CBE in 1967.[8]

In 1934, Rodger married Jean Chalmers.[9] They had three children: a daughter, Christine, who became a doctor, practising in cardiology and acute general medicine;[10] a younger son, Ian, who became a quantity surveyor; and an elder son who was Alan Ferguson Rodger, a prominent lawyer, Lord Rodger of Earlsferry and Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom.[11] Though Rodger possessed many connections to Scottish psychoanalytic circles, he enjoyed a particularly long friendship with John Derg (Jock) Sutherland (1905-1991),[12] who became Medical Director of the Tavistock Clinic in 1947 and, after his retirement, helped to establish the Scottish Institute of Human Relations in 1970.[13] Outside of work, Rodger was enthralled by computers and cybernetics, enjoyed ‘sketching’[14] and was a keen ‘bird-watcher’.[15] Rodger retired in 1972 due to illness in the final year of his professorship and suffered ill-health until his death on 1 June 1978.[16]

My PhD research focused primarily on Rodger’s personal papers held at the University of Glasgow Archives Services.[17] This collection retains a plethora of material from Rodger’s work life including copious typescript and manuscript draft lectures, talks to public and professional audiences, correspondence and intricate patient case records. Rodger’s career, as reconstructed from these papers, supplemented by other archival and published documents, can be viewed as an absorbing opening onto developments in twentieth-century psychiatry. Thus far, the published articles which have stemmed from my PhD have centred upon the interwar and post-war period. In an article for History of the Human Sciences, I explore how Rodger’s heretical psychoanalytic-psychotherapy unfolded within the so-called ‘dream books’, labyrinthian patient case histories recording the dream analysis of five male patients in the 1930s. In these books, Rodger’s contrasting therapeutic allegiances to Freudianism and a pragmatic ‘commonsense’ psychotherapy coalesce, allowing the patient’s shifting trust in and resistance to psychoanalysis to emerge.[18] In a co-authored paper for Cultural Geographies, Prof Chris Philo and I bring Rodger’s interwar psychoanalytic-psychotherapy into dialogue with the ‘new walking studies’, exploring a patient-authored account of a walk in Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens as a ‘psychiatric-psychoanalytic fragment’.[19] Finally, the first paper I published during my PhD contextualises Rodger’s post-war eclecticism, a combination of physical, psychological and social approaches, in relation to his psychiatric education as well as the deinstitutionalisation of psychiatry and the insufficiency of knowledge around certain treatments in the 1950s and 1960s.[20]

Although the archive offered up a rich and cogent portrait of Rodger’s career, oral history-type testimony summoned those more elusive and emotive elements of his life. Rodger’s daughter Christine and son Ian elaborated on Rodger’s youth, disposition and interests, while former colleagues elucidated how his psychiatric leadership manifested and how his personality affected the direction of his psychiatry. These interviews are qualitatively distinct from the archival material I examined, disclosing how Rodger was thought of or remembered by others. They offer a more impressionistic portrait of his standing in relation to his psychiatric contemporaries. In particular, they convey how Rodger was unique or atypical at least in fostering the collegial exchange of psychiatry and psychology. Kenneth Clarke, a psychologist who worked in Rodger’s department, stated that ‘one of the hallmarks’ of Rodger was his integration of psychoanalytically inclined staff with ‘quite hard […] biologically minded psychiatrists’.[21] The psychologist Professor Gordon Claridge evoked the genial, egalitarian atmosphere of Rodger’s department which facilitated this eclectic collaboration. Claridge explained how the department,

was just an unusually relaxed place, both personally and from a professional point of view […] there was nowhere else in the country, I don’t think, where psychologists and psychiatrists could get on so well, were almost treated as an equal really in the face of, you know, a certain amount of tension between psychiatry and psychology and, you know, it was a very rewarding period of my life I have to say (LAUGHS) and, you know, very enjoyable as a place to work […] It was just Glasgow and somehow the department fitted into that, you know, a sort of rather warm inviting place really.[22]

It is difficult to see how something as subjective and evanescent as the sense of easy community recalled by Professor Claridge, and indeed also by his colleagues could be conjured as vividly, if at all, from the written texts in Rodger’s archive.

Rodger was memorably characterised by a psychiatric colleague, Dr Reginald Herrington as ‘too principled, too honest’ and a person who ‘could see a problem from every angle’ (Herrington Interview 10).[23] Researching developments in twentieth-century psychiatry through the biography of a self-effacing and self-critical figure such as Rodger has likely benefited my research, making visible some of the difficulties and instabilities of psychiatric practice during that period, potentially hidden by a more self-satisfied practitioner.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Louise Scollay for assistance and advice during the preparation of this blogpost. I would also like to thank the individuals I interviewed for my PhD. I am grateful to the University of Glasgow Archives and Special Collections for permission to reproduce an image of Thomas Ferguson Rodger in this blogpost and to NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Archives for permission to reference archival material. Thanks also to Dr Gavin Miller and Prof Chris Philo for discussing this research with me during my PhD.

This blogpost draws on PhD research which was funded by a Lord Kelvin Adam Smith PhD Scholarship from the University of Glasgow.

[1] ‘Biography of Thomas Ferguson Rodger’, (26 February 2013). University of Glasgow Story. http://www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk/.

[2] Christine Rodger: Personal Communication.

[3] Christine Rodger, Interviewed by Sarah Phelan, 2 December 2014, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh, 13.

[4] ‘Biography of Thomas Ferguson Rodger’, (26 February 2013). University of Glasgow Story. http://www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk/.

[5] A.M.S. (1978) ‘Obituary: T. Ferguson Rodger’, British Medical Journal 1(6128): 1704.

[6] Christine Rodger: Personal Communication; Letter of application, 26 April 1937, Dr Thomas Ferguson Rodger (c.1933-1963), Staff Records of the Physician Superintendent, Records of Glasgow Royal Mental Hospital, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Archives, Mitchell Library, Glasgow, HB13/20/179, 2.

[7] A.M.S. (1978) ‘Obituary: Professor T. Ferguson Rodger’, The College Courant 30(61): 39; Letter of application, 26 April 1937, pp. 2–3.

[8] A.M.S. (1978) ‘Obituary: Professor T. Ferguson Rodger’, The College Courant 30(61): 39; A.M.S. (1978) ‘Obituary: T. Ferguson Rodger’, British Medical Journal 1(6128): 1704; ‘Biography of Thomas Ferguson Rodger’, (26 February 2013). University of Glasgow Story. http://www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk/; Timbury, G. ‘Obituary: Thomas Ferguson Rodger.’ Psychiatric Bulletin, 2(10): 169.

[9] Christine Rodger: Personal Communication.

[10] Christine Rodger, Interviewed by Sarah Phelan, 2 December 2014, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh, 1.

[11] Administrative/Biographical History for Papers of Thomas Ferguson Rodger, 1907– 1978, Professor of Psychological Medicine, University of Glasgow, Scotland (Archives and Special Collections, University of Glasgow, May 2012); accessed (16 August 2021) at: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/89c87074-8f6c-33e7-8811-b9960fa6c1b0.

[12] Christine Rodger, Interviewed by Sarah Phelan, 2 December 2014, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh, 6.

[13] Haldane, D., and Trist, E. ‘Obituary: Jock Sutherland.’ British Journal of Medical Psychology, 65, (1): 3.

[14] Christine Rodger, Interviewed by Sarah Phelan, 2 December 2014, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh, 11, 12.

[15] Ian Rodger, Interviewed by Sarah Phelan, 26 January 2015, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh, 12.

[16] Timbury, G. ‘Obituary: Thomas Ferguson Rodger.’ Psychiatric Bulletin, 2(10): 169-170.

[17] Thomas Ferguson Rodger Papers, 1907-1978, University of Glasgow Archives and Special Collections, GB 248 DC 081, Catalogue can be viewed at: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/89c87074-8f6c-33e7-8811-b9960fa6c1b0.

[18] Phelan, S. (2021) ‘A “Commonsense” Psychoanalysis: Listening to the Psychosocial Dreamer in Interwar Glasgow Psychiatry’, History of the Human Sciences (34)3-4: 142-168.

[19] Phelan, S. and Philo, C. (2021) ‘“A Walk 21/1/35”: a psychiatric-psychoanalytic fragment meets the new walking studies’, Cultural Geographies (28)1: 157-175.

[20] Phelan, S. (2017) ‘Reconstructing the Eclectic Psychiatry of Thomas Ferguson Rodger’, History of Psychiatry 28(1): 87-100.

[21] Kenneth Clarke, Interviewed by Sarah Phelan, 31st January 2015, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh, 3.

[22] Gordon Claridge, Interviewed by Sarah Phelan, 30th January 2015, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh, 10.

[23] Reginald Herrington, Interviewed by Sarah Phelan, 8th December 2014, School of Scottish Studies Archives, University of Edinburgh, 10.

Dr Sarah Phelan is an Affiliate in School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow. She was awarded a PhD in Medical Humanities from the University of Glasgow in 2018. Prior to this, she undertook an MSc in the History and Theory of Psychology from the University of Edinburgh. She has published peer-reviewed articles in the journals History of Psychiatry, Cultural Geographies and History of the Human Sciences. Her research interests include the history of psychiatry, the history of psychoanalysis, and the history of dreaming.

Images are copyright to those attributed in the captions and used with kind permission