As the first in our series of blogs as part of ‘Queering the Archive’ initiative, I discuss some infamous ‘cross-dressing’ ballads within our collections.

Here at the School of Scottish Studies, we hold many records of the popular cross-dressing ballads that exists in Scottish oral tradition and traditional songs. Protagonists of these forms of ballads and songs are often women. These ballads involve a humorous tale of women in forms of drag and concealment as a way to engage in male public life or work. Common forms of this are cross-dressing sea-ballads that describe the protagonist entering the workforce. Women were excluded from joining the ranks of the navy and any work at sea was relegated into different roles for men and women. As such, the selected ballads can be viewed as a way of subverting gender roles and societal expectations through drag and cross-dressing. While these are not necessarily queer stories, we can apply queer theory to these records thus allowing us to queer the archive and Scottish sounds.

This blog was originally created in mind to not only provide my own point of interest in just some of the examples of the ‘queer’ in the archive but to introduce application of theory and some of my own thoughts to the records. Though I do not see these as records of particular LGBT+ identity, they are examples of the ‘queering’ of records and application of queer theory.

Content warnings apply within this blog and for some of the sound material for sexual content, issues in consent, and themes and depictions of gender that some may find uncomfortable.

The first ballad to be discussed is “The Banks O’ Skene”, which describes how a young female protagonist sought work in the navy and disguised herself in “men’s clothing”. The protagonist is apprenticed to a heckler and sings of how “the girlies all fell in love with me below The Banks O’ Skene.” This can be seen as subversion of expected gender roles and exploration of sexuality and performance that wouldn’t often be afforded to women. However, later in the ballad the protagonist is discovered by her master and the ballad continues with bawdy descriptions of exposure of identity, drinking, and her master, “taking her maidenhead” and the ballad ending in pregnancy and marriage. While intended as a humorous tale, it reflects issues and attitudes of the life of women working on ships and the reasons given why women working aboard naval vessels were frowned upon due to notions of sexual relationships, pregnancy, and conflict. Through application of queer theory, this turns into a tale of a female protoganist gaining freedom in male fields of work and performance, but ultimately having to fall to her expected female role of sex and marriage.

Another example of a similar style of cross-dressing ballad is “The Handsome Cabin Boy”, in which the female protagonist disguises herself as a young cabin boy. She is described by the sailors as handsome and pretty in most versions of the ballad, while she is still ‘disguised’ as male. Her identity is only ‘discovered’ once she gives birth to the Captain’s baby. This song is similar in style and content as “The Banks O’ Skene”, again singing of the benefits of navigating the world disguised as a man, and later the problematic exposure narrative and relegation of roles of birth and marriage. A different queer narrative can be applied to this in the example of the hidden sexual relationships of sailors and the attraction the other sailors felt towards the protagonist when she was viewed as “The Handsome Cabin Boy”.

There is also another known cross-dressing ballad of “Billy Taylor”, or “Willy Taylor”. A jilted lover of Billy Taylor disguises herself as a man and finds work aboard his ship. She discovers Billy with another woman and shoots him. The Captain of the ship is so impressed by the bravery and act that he makes her commander of the ship and gives her a hundred men. This ballad is different from “The Banks O’ Skene” and “The Handsome Cabin Boy”, as while it does involve the typical problematic and often times literal exposure narrative of these ballads, it does not feature a sexual relationship that ends in discovery and pregnancy. It instead follows the ballad and protagonist archetype of a romantic heroine that takes revenge on her cheating lover. This ballad begins and ends with subverting gender roles through taking on work as a man of lower status on the ship to ultimately becoming highly ranked to a Captain when the protagonist is no longer ‘cross-dressing’.

Not all cross-dressing ballads follow a life at sea. There is also the ballad, “The Famous Flower of Serving Men”, in which the female character of ‘young Ellen fair’ cuts off her hair and becomes ‘young Willie Dare’ after an attack on her life and child by her step-mother. She later goes to find work dressed as a man, and gains a job in the castle, initially as a stable boy. However, because Young Willie Dare is so handsome, which is acknowledged by her Master and the working men, she gains rank as a serving man. The Master later finds out her identity and marries her because she is so beautiful and handsome. Other ballads follow the young protagonist entering the military, such the group of ballads, “The Female Drummer”, “The Solder Maid”, and “Wi my Nice Hat and Feather”. The groups of ballads also involve similar narratives of entering the male sphere of work and roles in the military, with some queer attraction. In the version of “The Female Drummer” sung by Margaret Jeffrey, it is noted that “Although [the protagonist] pretends to be a young man, she is so beautiful that another girl falls in love with her”, however it is also related to aspects of heteronormativity by the end of the ballad, “She is told that if she ever gets married and has a son, she should send him to learn to play the drum.”

We also hold many more examples of these types of ballads, as well as examples of cross-dressing ballads where men were dressed as women. This is also often used as a form of anecdotes and tales, where men were dressed up to escape a skirmish or the authorities. The most famous of these songs surround Bonny Prince Charlie dressing up as a female maidservant to escape to the Highlands, which includes the songs “Moladh Mòraig‘ [Marion’s Wailing”’, and many more. Other examples of this cross-dressing narrative, includes the tale of “Mac Iain Bhàin Ghobha and the robbers”. The Gaelic tales describes how Mac Iain Bhàin Ghobha’s partner leaves for America to find where work as a servant. She is later captured and taken to a cave of robbers, in which she finds Mac Iain Bhàin Ghobha dressed as a woman. They fight and deal with the robbers and gain money for bringing them to justice. They both marry once they return to Scotland with their new riches. The majority of these ballads or tales are Romantic in nature and feature a brave heroine, a daring protagonist, or forms of escapism and running away and heroics. It is notable that most of these ballads and tales also end in finding love in heterosexual marriage, thus relegating any subversion of binary gender roles or examples of any kind of sexual fluidity and exploration back to the traditional heterosexual spheres of marriage.

We can apply queer theory to these records in the sense that the ballads often explore subversion of binary gender roles and include some form of queer attraction and aspects of fluidity. However, these ballads are often told and passed down through a cisgender and heterosexual lens. Some ballads reduce queerness and cross-dressing to mockery, and at times, danger. Themes of deception can be common which can make some an uncomfortable listen when considering themes and narratives of these forms of ballads. Almost all of the ballads in our collections end in a heterosexual marriage and raises questions about the context of expected societal roles and views of fluidity. Queering the Archive will allow us to analyse these records and more through queer theory within the workshops and beyond.

The records discussed in this blog are available for listening on Tobar an Dualchais:

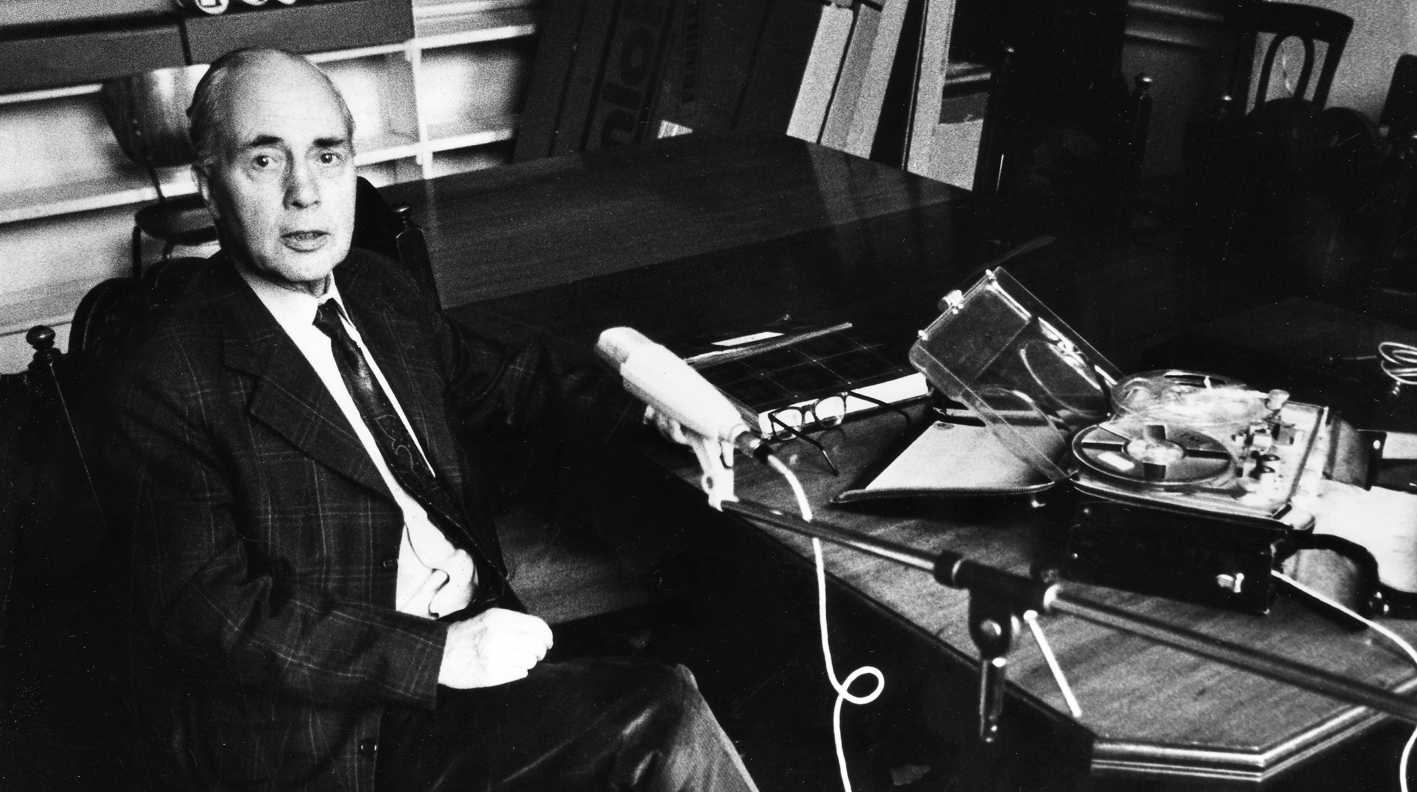

“The Banks o Skene”. George Hay recorded by Hamish Henderson. Aberdeenshire, Skene. SA1957.17.A3 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/20800

“The Handsome Cabin Boy”. Jeannie Robertson recorded by Hamish Henderson.

SA1954.72.B8 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/2363

“Billy Taylor”. Robb Watt recorded by Arthur Argo.

SA1960.255.A4 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/82824

“The Famous Flower of Serving Men”. Jeannie Roberston recorded by Hamish Henderson, SA1954.103.A1; SA1954.103.A2, 525 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/38037

“The Female Drummer” Margaret Jeffrey recorded by Hamish Henderson.

SA1956.123.A5, http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/20185

“The Female Drummer”. Donald George Gunn recorded by Donald Grant.

SA1963.87.A9 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/48437

“The Soldier Maid”. Rob Watt recorded by Arthur Argo.

SA1960.253 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/59181

“The Drummer Maid” James Laurenson recorded by Alan J. Bruford.

SA1973.62.A5 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/75663

“Wi my Nice Hat and Feather”. Jimmy Taylor recorded by Hamish Henderson.

SA1952.32.B18 (B25) http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/46812

“Moladh Mòraig”. Pipe Major Robert Bell Nicol recorded by Pipe Major Neville MacKay.

SA1964.264.B2 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/71946

“Mac Iain Bhàin Ghobha agus na robairean” Angus MacLellan recorded by Donald Archie MacDonald, SA1963.57.A2 http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/78752

(There are also other versions of these ballads on Tobar an Dualchais. To find our records, select School of Scottish Studies only within Advanced Search. All of our records will be listed under SA.)

If you are interested in taking part in Queering the Archive workshops, or if you are interested in researching LGBT+ records or using our collections for your work, please contact eholmes@ed.ac.uk

Written by Elliot Holmes.

Elliot is one of the Archives and Library Assistants at the School of Scottish Studies Archives and uses He/They pronouns. You can also find him on twitter @elliotlholmes

Follow @EU_SSSA on twitter for updates and sharing our collections.