We are incredibly grateful to Morag Macleod, who has written this week’s post about her recollections of Tocher and her wider work in the School of Scottish Studies, working with Gaelic material.

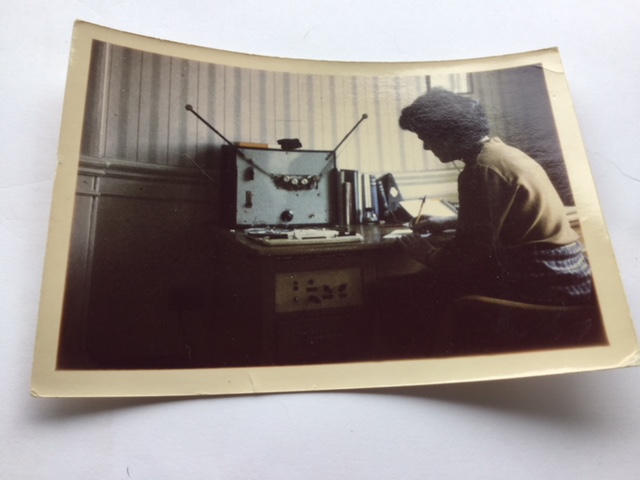

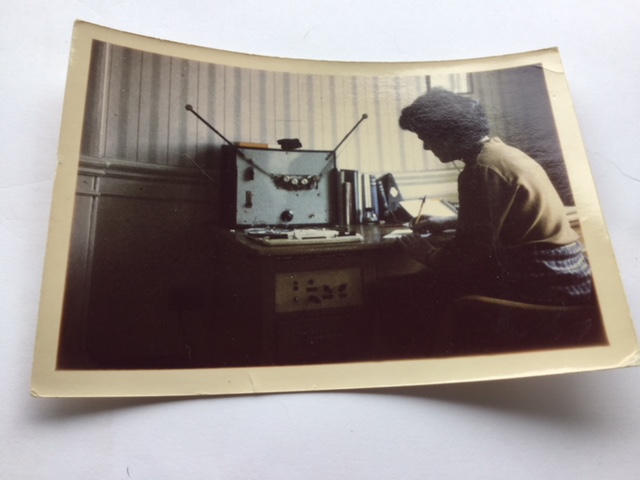

I was very fortunate during a break in my undergraduate career to be asked to fill the recently vacated post of Texts Transcriber in the School of Scottish Studies. That was in 1962, and my work was to write Gaelic stories and interviews and the words of Gaelic songs. The material was mainly on 5” and 7” tapes, and some of those were in a bad way. With storing conditions that were not ideal, the tapes tended to dry, and this made them brittle. After a time I would sometimes make an attempt to collect the bits of tape that scattered around, and mend them, but it was mainly the work of the technicians to make the best of that. A story went around of a comment by Calum Maclean when bits of tape landed on the floor, “Catch that tape, it might be a grace-note”.

A device, a repeater, invented by Fred Kent, the chief technician, was indispensable for me. A short piece of spoken or sung text was recorded on to a short loop which could be played over and over to facilitate making a correct interpretation of the item on the original tape. As texts transcriber, I was given recordings from Harris , the easiest for me to understand. That material was then added to files in the library, ready for typing when required.

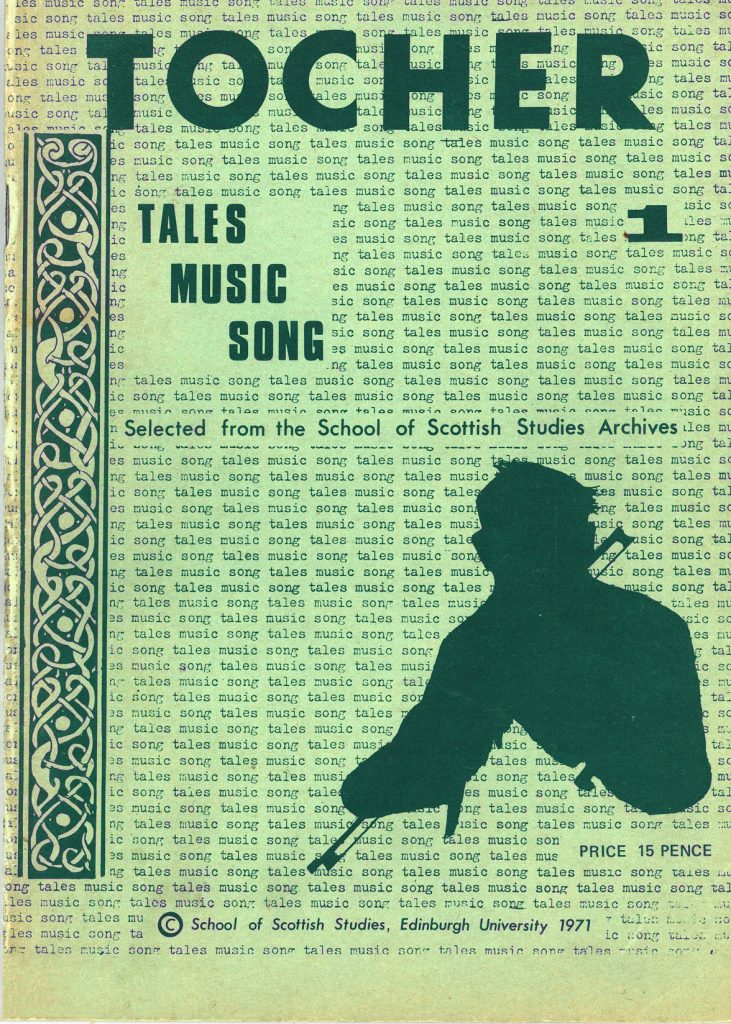

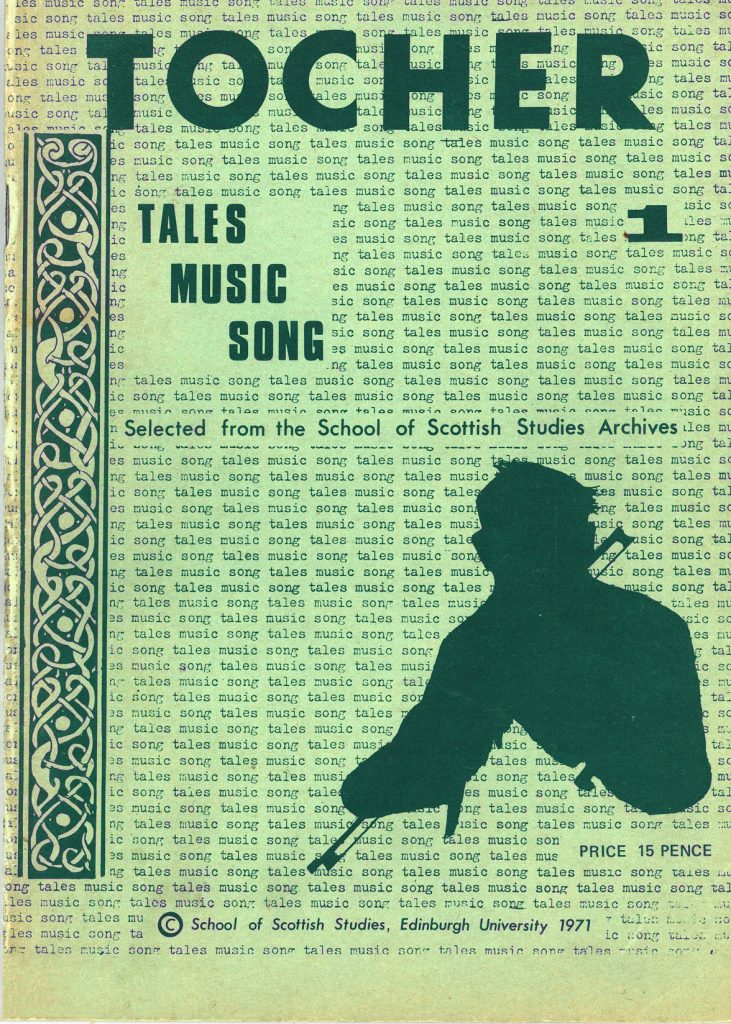

In my time, Mary Macdonald did most of the typing, and that familiarised her with the richness of the material, and encouraged in her the strong wish that it should be seen. Mary’s roots were in Islay although she had lived for some time in Barra. She loved the material held in the School and she it was who thought of publishing it, with eager support from Dr Alan Bruford. Dr Bruford was then the editor, with Mary his assistant. Between them they came up with an A5-sized booklet, Tocher, TALES, SONGS, TRADITION, SELECTED FROM THE ARCHIVES OF THE SCHOOL OF SCOTTISH STUDIES.

The basic English translation of the Gaelic word Tochar is dowry, but it can convey collection or treasure, and had the advantage for us of having a similar sound in English or Scots.

All members of staff were required to contribute to the booklet, leaving the choices and editing to Alan and Mary, and Donald Archie Macdonald, Cathie Scott and Joan Mackenzie were amongst those who were involved in its production over time, as well as Tony Dilworth. Ralph Morton contributed fine illustrations by hand and edited photographs.

Personally, I was advised to write the Gaelic material in a way that let the reader know how the informant pronounced the words. Of course I couldn’t be given the luxury of confining myself to my native Scalpay, Harris, Gaelic, and I remember well some difficulty I had with a waulking song from Lewis. Waulking songs accompanied the rhythmic beating of tweed on to a board in order to wash it and shrink it. The form was solo and chorus, and a lot of the texts were spontaneous. The performer (and author) had to be familiar with the concept of assonance, at the ends of lines or between a word at the end of a line and one in the middle. O mo leannan, é mo leannan (Oh, my sweetheart, ay, my sweetheart) is the refrain to a very popular waulking song. There is a verse that goes:

‘S e mo leannan am fear donn

A chì mi ? a’s an taigh-chiùil.

My sweetheart is the brown-haired

one whom I can see ? in the ceilidh-house.

That ? word had to rhyme with donn, which is pronounced like English down. My colleague John Macinnes had to tell me that it was bhuam (along / across from me, pron. voo-um in my dialect) which would be pronounced like fomm = fowm in Lewis.

A greater leap was when John MacInnes asked me to transcribe stories and songs from the traveller Alex Stewart . His Sutherland Gaelic was very different from mine, and that created a steep learning curve for me. I was given me a lifelong awareness of the ties of spelling with pronunciations, especially in Gaelic.

Alexander Stewart, photograph by Sandy Paton

SSSA-HH14

An incident that stays in my mind connected with my contributions to Tocher is when I chose a song from the archive that I had known from childhood, to fit in with a fishing, sailing theme. I actually made no claim for its provenance, – thank Goodness, although I had thought it might possibly be from my native island – but that the singer was from Scalpay. In the next issue of Tocher , No 20, there was a notice from Dr John Lorne Campbell of Canna to say that the song was a version of one by John Campbell of Lochboisdale, South Uist, and was published in Orain Ghàidhlig le Seonaidh Caimbeul by J. MacInnes and J.L Campbell in 1936. The notice in Tocher was probably much more polite than Dr Campbell’s private comment. Incidents such as those two made me aware of the tremendous knowledge there was around about the simplest things that I had taken for granted over the years, and of how ignorant I was.

After a year another vacancy occurred when Gillian Johnston resigned as music transcriber. I had done Higher music in school, but I did not see myself as competent to produce written versions of melodies. When approached by the current musicologist, Thorkild Knudsen, a Dane, I tried to explain my limitations to him, and he boosted my morale so much by saying “You’re not the best, Morag, you’re the only one.” It is hard to believe now that at that time that was true. Anyone who had qualifications in music did not see this work as at all prestigious, and their being literate in Gaelic was immaterial. It was to the credit of Prof Sidney Newman, head of the Music Faculty in the University, that he was an enthusiastic member of the academic board of the School of Scottish Studies at its beginnings, but such a combination was unusual.

Transcribers in Tocher, apart from me, produced a tremendously accurate reproduction of the singer’s performance. One example of a song learned from the magazine showed me that an indication of speed was advisable. I hear the song on radio and the vocal reproduction is, to me, so slow as to be unrecognisable. Dr Emily Lyle at one time tried hard to persuade us to put together a collection of the material in Tocher, and I confess that I resisted that idea, which I now see is a pity – Sorry, Emily! It would, especially with, perhaps, some further editions have been an asset to folklorists.

But, how things have changed. Even by the 1960s, more attention was being given to Gaelic music in education, and the interest of the Royal College of Music in Glasgow giving classes in Gaelic singing and piping, quickly brought about a greater prestige to the subject. Some of the first students from there – later the Conservatoire – are really well-known now. Tobar an Dualchais, was established officially in December 2010. It consists of archive material, mainly from the School of Scottish Studies, Canna and the BBC. It has made an incredible difference to the general knowledge of traditional Gaelic music.

Now there is a change in attitude to the rights of the informants. There were different kinds of implication in collecting traditional material. Sometimes we would be asked, “So when will we hear it?” as employees of the BBC were the most familiar carriers of microphones and recorders. Others would almost require an oath that it would not be heard by anyone outwith the department. I remember one occasion when someone who had given us a large number of songs said something like. “Why should I give you songs when you just give them away to any Tom Dick or Harry?” (I won’t try to think of a Gaelic form of that). A well-known singer had sung a song on radio which could only have come from one of our recordings and was completely recognisable as that. Of course, if a song or story was selected for use on radio, forms were produced for permissions. Mary Macdonald saw the publication of a portion of the material as a way of passing on the treasures that she loved whilst keeping to the desire for confidentiality to a reasonable extent, and Tocher fitted her wish perfectly.

With Tobar an Dualchais there is little need to produce something like Tocher, and the last issue, no. 59, came out in 2009. I was responsible for one issue and was really surprised at the amount needed to provide a reasonable volume. It is still, I think, useful for items relating to particular themes, and particular informants.

Morag has was involved with several roles and projects in The School of Scottish Studies from music transcriber, fieldworker, Senior lecturer in Gaelic song, and working to create Tocher and the Scottish Traditions Series. Morag is now retired, but she remains a valuable touchstone of knowledge for us at the Archive. Thanks to her once again for writing about her memories of The School and Tocher.

If you would like to listen to some of Morag’s fieldwork recordings for The School of Scottish Studies Archives, you can listen to over 1000 tracks on Tobar an Dualchais.

Please do not reproduce images without prior permission.