Do you suffer from paraskevidekatriaphobia or Mavrogatphobia? Perhaps don’t read on!

Today is Friday, 13th August – Friday the Thirteenth! The day, it is said, that is purported to be unlucky or be shrouded in superstitious or even supernatural belief, although nobody really knows why! Nevertheless, we are always keen for an opportunity to delve into the collections related to superstitions.

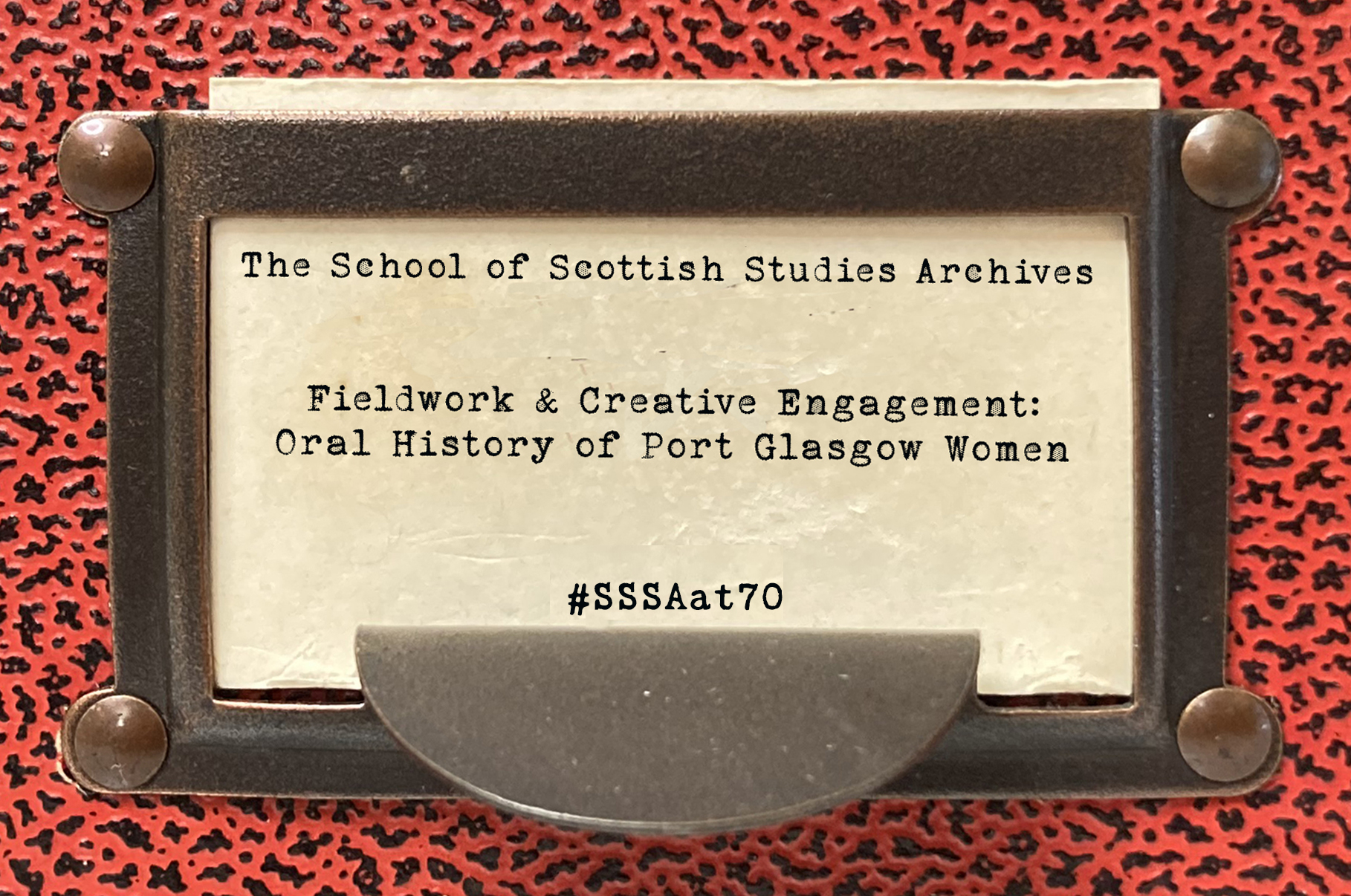

I found this letter in a box of correspondence (SSSA/Box141) related to Alan Bruford, Archivist and lecturer at the School of Scottish Studies. This letter was sent from a school in Aberdeen by Class 1K and is dated January 1980; the query is on black cats and luck! The class had been learning about superstitions, but had a burning question for Professor John MacQueen, the Director of The School of Scottish Studies at that time.

“Most of the things [superstitions] that we have thought of we have found a solution to them, but there is one thing that has had us puzzled, BLACK CATS. We don’t know why they are lucky or unlucky, so that is why we are writing.”

The letter was signed by 19 students.

You can really feel that sense of bewilderment and that vehement thirst for knowledge of Class 1k.

As you can see, the secretary at the School was perhaps unsure who was best to answer this question and suggested Alan Bruford or Jack [John] MacQueen might have the answer. But did they? Did Class 1K get a response?

Often with correspondence such as this, a copy of the response was kept with the letter and there was no response with this one. I hope that we might be able to give some information today, if it isn’t too late.

page 81 of “The cat, a guide to the classification and varieties of cats and a short treatise upon their care, diseases, and treatment” (1895)

It is true, there are conflicting reports – sometimes Black cats seem to foretell good and bad luck. Perhaps one reason for this is that black cats were associated with being the devil or with the alleged ill doing of witches. The persecution of people as witches is a blog post for another day!

Perhaps (like “witches”) it’s all down to individual beliefs and who the luck is intended for. Often the cats came off worse! Here are a few examples from our collections.

Bad Luck?

Nan MacKinnon told Anne Ross about a black cat that followed a man who had jilted his wife. The man’s mother had to speak to the minister before the cat, mysteriously, stopped appearing. Was this black cat really a wronged woman, come to seek out revenge?

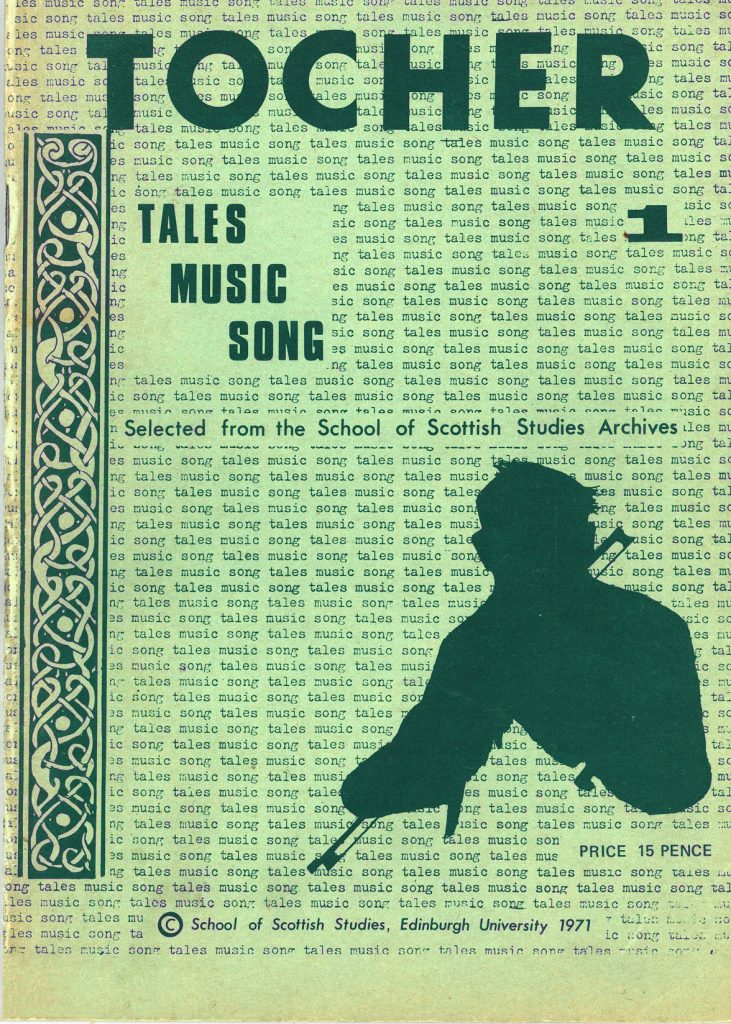

BANA-BHUIDSEACH MAR CHAT. Nan MacKinnon (contributor), Anne Ross (fieldworker). SA1964.078.B. https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/track/23715

In the Maclagan Manuscripts (1893-1902) there are a few mentions of Black cats and mostly of them related to bad luck. A female contributor in Newhaven, Edinburgh, told if men were to meet a black cat on their way to go fishing, they would just say to one another ‘We hae gane far enough the day’, and they would turn back, for they would be quite sure their luck was gone. (MML8840)

This practice was also observed in St Ninians; miners there held that it was unlucky for one to meet one. When they returned home after the encounter, they did not go out for the rest of the day, simply on account of a black cat having crossed the road before them! (MML9112). Also from Maclagan is a statement from an Lewis contributor, who stated that the breath of a black cat was pure poison (MML3847a)

Good Luck, but for who?

Another entry in the Maclagan manuscripts details another fishing-related black cat tale, this time from Westray, Orkney. An old man was often asked to secure good weather for the fishermen and he did this by putting a black cat under a creel while the boats were out. On one occasion a boy (who became the reciter’s brother in law in time) let the cat out for mischief. This apparently caused a sudden storm at sea from which the fishermen managed to escape from (MML 6771-6772).

Donald John Stewart, of South Uist, told a curious tale of a Glasgow man who went to stay in the highlands for his health. An old woman told him about a particular mirror in one room in the house he was staying in, and said that anyone who looked in it when the full moon was shining on the sea outside would turn into a cat. The man did just that, and turned into a big black cat. The old woman then told his family to submerge the cat in the well seven times by the light of the full moon, and that when they let him go the seventh time, he would be restored!

AN SGÀTHAN ANN AN TAIGH COIRE BHREAGAIN. Donald John Stewart (Contributor), Donald Archie MacDonald (fieldworker). SA1975.113.B3. https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/track/76886

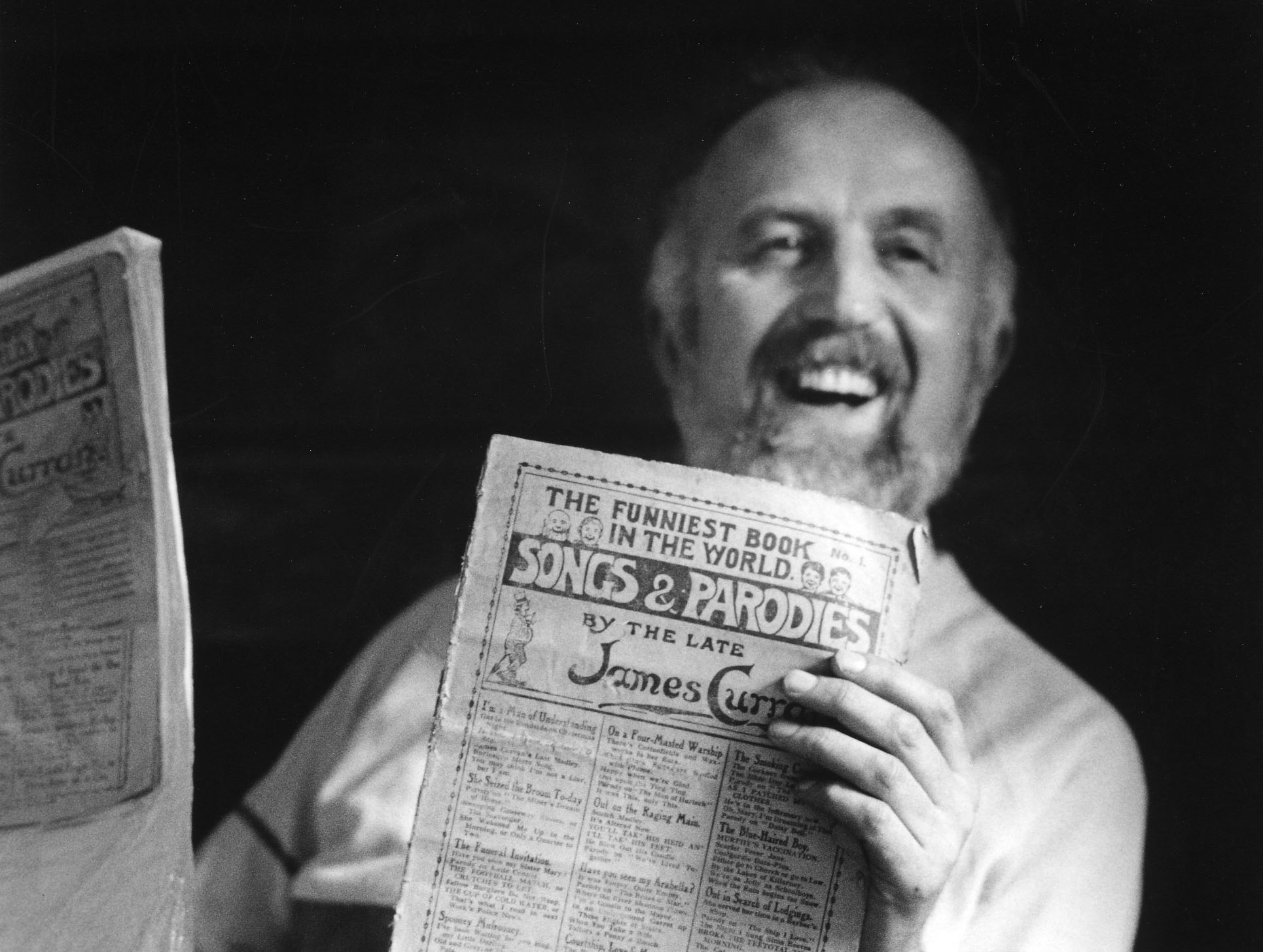

Stanley Robertson told a tale to Barbara McDermitt about a woman who sold her soul to the Devil for some wishes. Before her time came to spend the afterlife with the Devil, she wished to be young and beautiful and for her black tom cat to be made into a man to love her. Sadly – for both, presumably – ‘Big Tom’ was lacking somewhat!

An old spinster wished for her cat to be turned into a handsome young man, Stanley Robertson (Contributor), Barbara McDermitt (Fieldworker). SA1971.13.A1. https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/track/65452

Good Luck – they just are!

In my own upbringing I was always told that a black cat crossing your path was good luck indeed. According to my Nannie, they just are lucky!

I can’t find too many examples from our material available on Tobar an Dualchais, but Donald Sinclair, from Tiree. told John MacInnes that it was fortunate to have a Black cat around the place {SA1968.024) and Eileen McCafferty, from East Lothian, told Morag MacLeod and Emily Lyle that the tail of a black cat could cure warts (SA1974.24). If that isn’t good luck, then what is?!

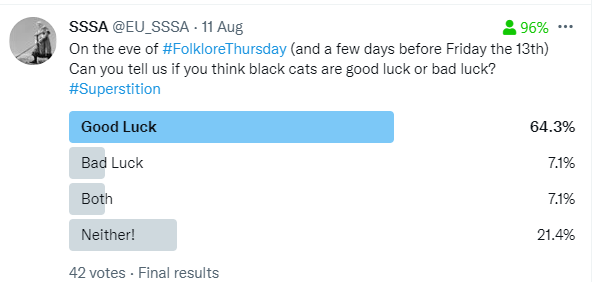

Thankfully, we don’t only have to look to the archives to find out the answer to the query. We took to the twitter hivemind and this is what they had to say (well, 42 of them!)

Class 1k, from Bankhead Academy, 1980 I think it is safe to say there is no real solution to this one.

What are your own thoughts, reader?

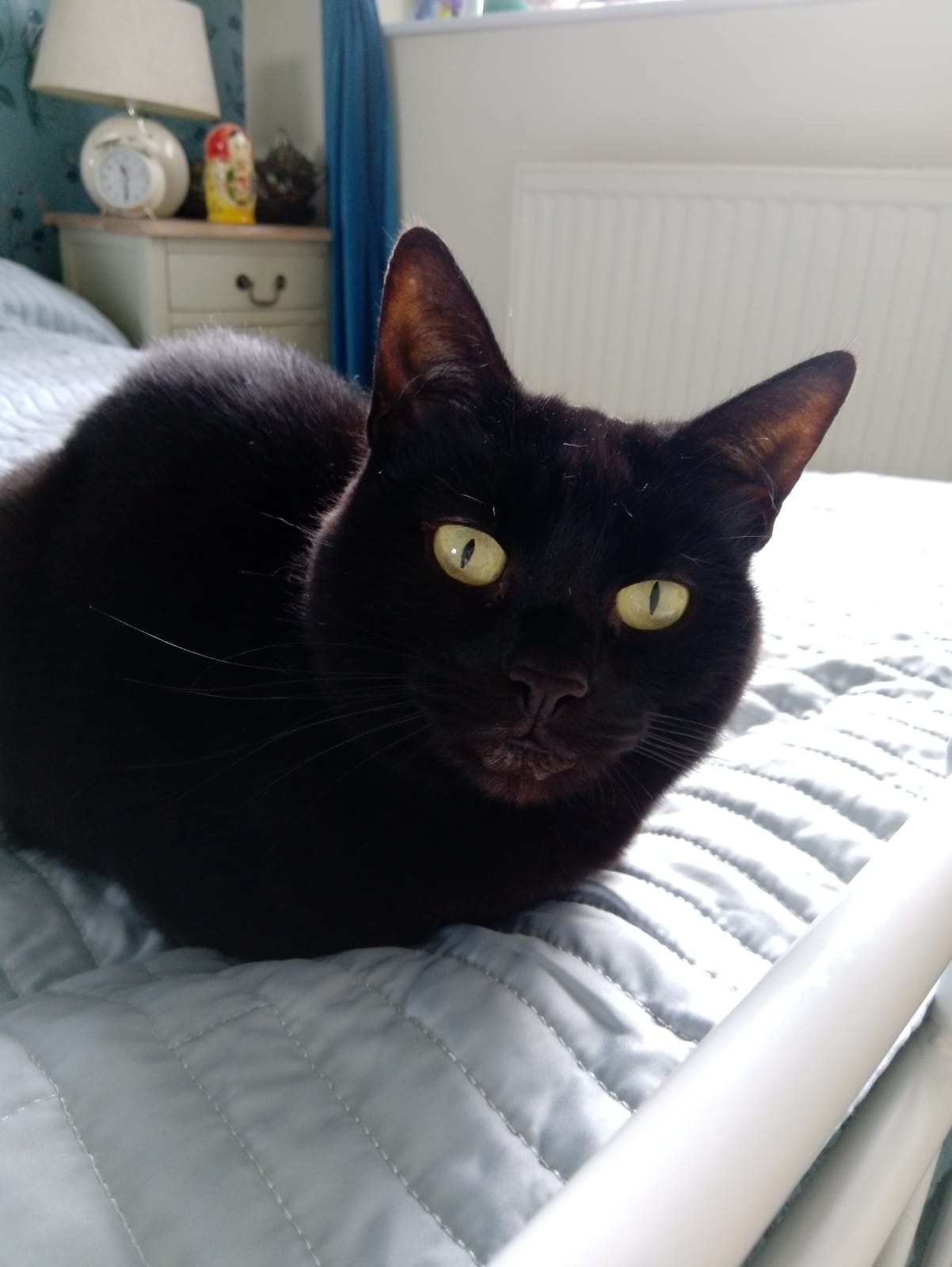

We will leave you to ponder your own superstitious beliefs with two bonny black cats belonging to Archive & Library Assistant, Elliot.