In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses her Decorated Paper rehousing project. If you want to learn about the uses, production, and trade of decorated paper, you can visit the online exhibition on this collection, curated by Elizabeth Quarmby Lawrence, here. Look out for the second post in this series soon, in which Robyn will discuss mounting loose leaf papers.

CRC: A Space Odyssey – Day in the Life of a Collections Management Technician

My name is Jasmine, and I’ve been working here at the University for five and a bit months as the Collections Management Technician. I’m the other half to Robyn Rogers’ role as Collections Care Technician, whose fantastic blog post about her recent work you can read here, and I work directly with the Appraisal Archivist and Archives Collection Manager, Abigail Hartley, whose equally wonderful blog post was featured last month.

Abigail did a great job of defining appraisal and the challenges to the archivist when it comes to choosing what material to preserve. The archivist is often put in the position of assessing the ‘value’ of the record, a thorny process which comes with a number of ethical challenges. Thinking through these problems, it might seem easier to suggest that we simply keep everything we receive. If we get to keep everything, we don’t have to think through complicated questions, like what is the purpose of the record? And what is the purpose of the archivist? After all, if something has found its way into the archive, isn’t that an implicit statement of its value? Why appraise at all?

Appraisal Made Easy (If Only…): A Day in the Life of an Appraisal Archivist

Welcome to our Day in the Life Series, where each of our new team members will give you an insight into life behind the scenes at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections. In this post, our new Appraisal Archivist and Archive Collections Manager, Abigail Hartley, discusses what she has been up to since joining the Heritage Collections team in March. Expect one more post in this series, as we introduce our Collection Management Technician, Jasmine Hide.

You may have seen the other week my colleague Robyn upload a new blog regarding her role as Collections Care Technician. If you haven’t… Go go go! Take a look at the fantastic work she has undertaken thus far. Once you have returned, it is my turn to introduce myself and the work I’ll be tackling for the foreseeable future.

Let’s start from the beginning, shall we? My name is Abbie and I have been working at the University of Edinburgh as its Appraisal Archivist since April 2023. These past three months I have been creating an appraisal process and enacting some practice runs on smaller collections in preparation of being let loose amongst the backlog of records held at the assorted Heritage Collections sites across campus.

But what even is appraisal?

Books, Boxes and Bugs! A day in the life of a Collections Care Technician at the Centre for Research Collections

Welcome to our new Day in the Life Series! The Conservation and Collections Management team recently recruited three new members of staff. In this series each of our new team members will give you an insight into life behind the scenes at The University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections. In this post, our new Collections Care Technician Robyn Rogers discusses what she has been up to since joining the team in March. Expect two more posts in this series, as we introduce our Appraisal Archivist and Archives Collection Manager, Abbie Hartley, and our Collections Management Technician, Jasmine Hide.

My first three months at the Centre for Research Collections have been jam packed – I have installed an exhibition, couriered a loan to the V&A Dundee, cleaned one hundred linear metres of rare books, and rehoused over seventy collection items – and that’s just a small selection of what I’ve been up to! On an average day you might find me jet setting across campus to move a harpsichord at St Cecilia’s Hall, or vising our offsite repository, the University Collections Facility, to clean some especially dirty books, before finishing the day in the Conservation Studio making some phase boxes. I feel fortunate to have worked with many fascinating collection items so far, from a Bible that had been rescued after falling down a well, to 60s pop stars’ microphone of choice. This demonstrates what I love about being a Technician working in cultural heritage – our work focuses on preventative collections care, as opposed to interventive treatment, allowing us to work with an exciting breadth of collections material.

The Book Surgery Part 2: Bringing Everything Together

In this blog, Project Conservator Mhairi Boyle her second day of in-situ book conservation training she has undertaken with Book Conservator Caroline Scharfenberg (ACR). Mhairi previously undertook a Maternity Cover contract at the CRC within the Conservation Department.

In the previous blog, the examination and initial steps in spine repair and board reattachment of two volumes from the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies (R(D)SVS) were described. The first blog in this series can be found here.

After my first session with Caroline, I sat down and pored over all my notes and the millions of photos I had taken. The amount of thought, precision and care that goes into book spine linings and repairs that will eventually be hidden and concealed shows how complex even in-situ book conservation steps can be. After jotting down my notes into a coherent order and cross-referencing everything with Caroline, I came back to the studio a few weeks later refreshed and ready for a full day of training and collaboration.

In this session, Caroline and I focused on making spine pieces and hollows, and examined how to reattach cracked book boards in different ways. One of the things I like most about working in Conservation is that we are constantly adapting and evolving techniques, tailoring them to the objects we are currently working on. This is exactly what Caroline demonstrated to me: informed by our initial examinations of both volumes, we tailored the treatment steps for each book based on its size, weight, and particular areas of weakness.

Recovering Silent Sounds

Image

In this blog, Veronica Wilson discusses her project working with musical instruments in storage. Veronica started this project as a Thompson-Dunlop Intern and then joined the Conservation & Collections Management team as a Library Assistant (funded by Thompson-Dunlop endowment and the Nagler bequest).

Wolfson gallery at St Cecilia’s Hall

The University of Edinburgh holds a rare and unique collection of musical instruments. Many stand proudly on display in St Cecilia’s Hall, the music museum of the University, visible to the public and played by musicians from around the world. The rest are in storage, available only by request for research, study, or viewing. The collection at the University Collections Facility (UCF) consists of instruments too large to be stored in any of the other locations. Though the time since they were last played can span lifetimes, the collection is anything but silent.

ICOM UK 2023

Today’s blog comes from Collections Registrar Morven Rodger, reflecting on the 2023 ICOM UK Conference in Glasgow, addressing legacies of colonialism nationally and internationally.

In August 2018, while on a courier trip in Washington DC, I paid a visit to the National Museum of African American History and Culture1. In one of the very first galleries I entered, a label mentioning the Earl of Dunmore caught my eye…

‘In November 1775 Royal Governor of Virginia John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, issued a proclamation that offered freedom to “all [indentured] servants, Negroes, or others… that are able and willing to bear arms” for the crown. But this promise was not fulfilled.’

I recognised the name immediately. John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore, built the Pineapple, an architectural folly a stone’s throw from my hometown. I knew about the building, and the symbolic significance of the fruit, yet here I was, thousands of miles across the Atlantic, being offered a new perspective on this familiar figure. I remember being struck that I’d had to travel all this way to hear the other side of his story.

The Book Surgery is Open: Learning the Art of Book Spine Repairs

In this blog Project Conservator Mhairi Boyle discusses her new role within the One Health project at the CRC, and the training she has undertaken with Book Conservator Caroline Scharfenberg (ACR).

In August, I started a new role as the Project Conservator for the One Health project within the Heritage Collections team. One Health brings together three archival collections which chart the development of animal health and welfare in Scotland. The collections in question are from OneKind, an animal welfare charity; the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RSZZ); and the University of Edinburgh’s Royal Dick School of Veterinary Studies (R(D)SVS).

One of the challenges of this project is the variety of material I am working with. Whilst most of the material is loose leaf archival papers and photographs, we also have many bound volumes. On the opposite end of the spectrum, we have chicken skeletons, animal medicines, vet tools, and graduation robes. In these cases, I will stick to preventive measures such as handling instructions and appropriate rehousing to enable ease of access and prevent any further damage.

Bearing Witness: The Pre-Digitisation Conservation Treatment of The Witness, Part 2

Today we have the second instalment of a two-part series by Projects Conservator Mhairi Boyle. Mhairi spent April 2022 working on The Witness, a collection of Edinburgh-based newspapers held by New College Library. You can read the first part of the series here.

The first instalment of this series focused on the contextual background and the condition of The Witness newspapers. In this final instalment, I will be discussing the ethical challenges of digitisation conservation work and reveal some highlight findings from the collection.

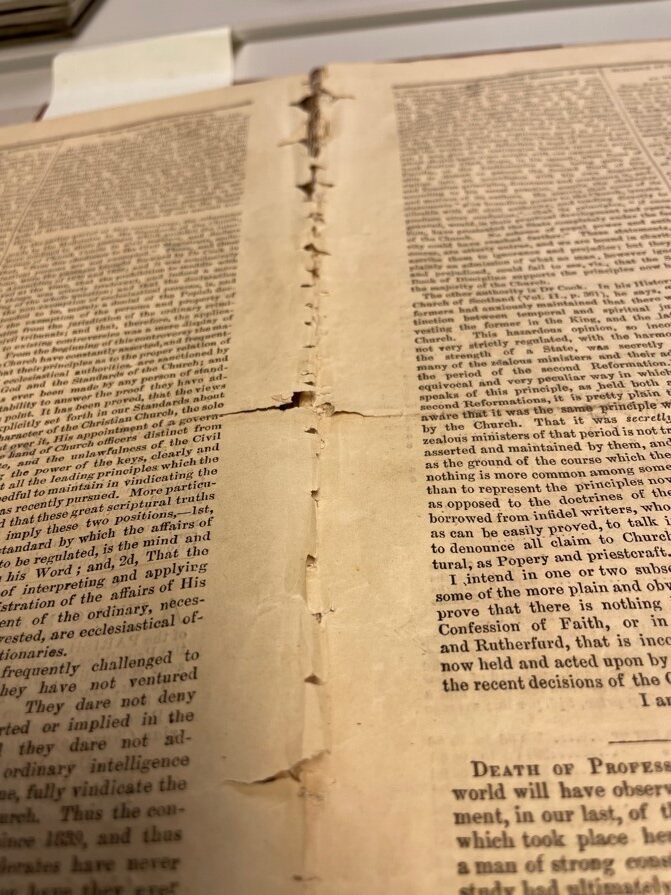

Weak and damaged areas.

In the Conservation team we often use the terms ‘pre-digitisation treatment’ and ‘post-digitisation treatment’. When assessing objects for digitisation, it is important to consider the condition of each object and how it will be digitised. If the pressing or scanning of an object will worsen its condition, pre-digitisation conservation treatment is often recommended. If there is damage to an object that will not be made worse during the digitisation process, then it can be flagged for post-digitisation treatment. In the case of The Witness, each newspaper will be laid flat, and each page scanned. This could worsen the split areas and areas of weakness when each page is turned for scanning. When each page is pressed, the tension from the old adhesive and thread holding each volume together could also create new splits and damage. This presented a new dilemma: we had to decide whether to keep the newspapers bound, or disbind each volume.

A Heavenly Rehousing Project!

Today we have the final instalment of a two-part series from Collections Care Assistant, Sarah Partington. In this post, she talks about cleaning and rehousing a collection of works by the Gaelic Baptist preacher and hymn writer, Padruig Grannd. Sarah has just completed a government-funded Kickstart placement and has now started a new role working with our collections at the University Collections Facility.

The Peter Grant Collection comprises volumes of works by the Gaelic Baptist preacher and hymn writer, Padruig Grannd. These were stored together in a box, along with other printed works, manuscript sermon notebooks, and items pertaining to one of his descendants, Daniel Grannd. The material was put together in the 50s and it had unfortunately experienced the effects of unsuitable storage conditions over the years prior to it coming into the care of the Centre for Research Collections. This was obvious from its condition: in addition to the more common issues with older books, such as surface dirt, loose boards, text blocks and spines, most of the items in the box also showed serious signs of mould, residual staining, and warping from damp conditions in past storage. Conservators and archivists alike will get shudders when they hear whispers of attics, basements or garages…the likely former home of this collection.