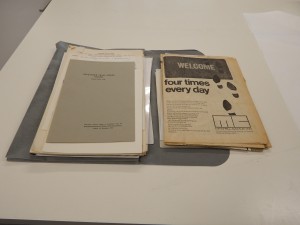

As a conservator, you can often find some rather surprising and unexpected ephemera in archive and book collections. Take, for example, this folder from the University’s Aitken Collection.

At first sight, it may seem like a fairly typical example of paper archive material. Upon closer inspection, however, there was a rather lovely surprise waiting inside.

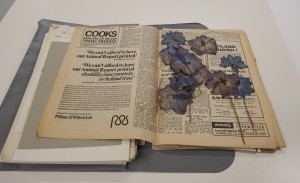

Pressed flowers are certainly not uncommon, but they can pose a rather tricky conservation conundrum; most ‘pressingly’ (pun-intended!) is whether the flowers should be left in-situ or removed and housed separately.

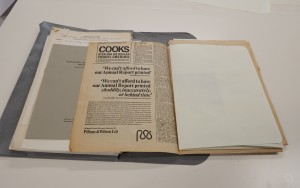

In consultation with archivist Neasa Roughan, the decision was taken to keep the flowers in-situ but re-house them in order to provide a protective interleaving layer between the flowers and archival material, thereby minimising the risk of any further deterioration. Furthermore, this will also improve access, make handling these pages easier and reduce the possibility of damage and loss to the flowers themselves.

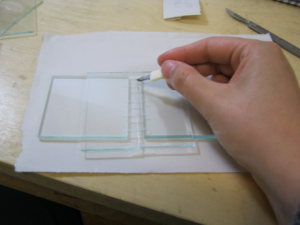

The choice of re-housing material and a knowledge of its manufacture is very important, as poor quality materials that are in close contact with collection items can cause severe damage. Acidity in poor quality materials can migrate to collection items causing discolouration and embrittlement, thereby hastening their deterioration. It was decided, therefore, to wrap the flowers in acid-free tissue, and make a 4-flap folder, also acid-free, in which to keep the flowers secure. This approach allows the flowers to be kept in their original location whilst providing suitable protection to the archive material, as well as the flowers, and helping to ensure the longevity of both items.

Neasa, who has been working closely with this collection, explains further:

“I found these beautiful pressed anemones among the personal papers of the eminent mathematician, A C Aitken. Aitken was born in Dunedin, New Zealand in 1895; he was the son of a grocer and the eldest of seven children. Following his military service during World War I, which took him to both the battle of Gallipoli and the Somme, he moved to Edinburgh where he had been awarded a postgraduate scholarship. He studied under Edmund Taylor Whittaker, and was awarded a D.Sc. in 1925. This was something of a surprise for Aitken, who had been working towards a PhD. Furthermore, this qualification was based on a mere 10 weeks work! He kept quiet about the latter fact, as he feared that his research would not be taken seriously if it was widely known that he found his solution so quickly.

Aitken progressed steadily at the University of Edinburgh, becoming reader in statistics in 1936, and gaining the chair of Pure Mathematics in 1946, where he remained until he retired in 1965. For a short time during World War II he worked at Hut 6 at Bletchley Park, though for obvious reasons little is known of his role there.

Besides his prodigious mathematical talents, Alexander Aitken was gifted in many spheres. He was a talented violinist and composer, wrote poetry and prose (he was awarded a fellowship of the Royal Society of Literature for his memoir Gallipoli to the Somme) spoke six languages, and had an eidetic memory (he could recite pi to 1000 places). Sadly, he was also a rather troubled soul and suffered greatly following his traumatic experiences during World War I. His prodigious memory ensured that he was unable forget his time spent in the trenches, and as a result of this he suffered severe nervous strain and insomnia.

I haven’t found many clues about where these lovely blue flowers came from – I believe that they are anemones. The newspaper they were originally pressed in dated from September 1967, two months before Aitken’s death. Wood anemones do grow in Scotland, and Aitken was a keen walker in the hills around Edinburgh so it is possible he picked them himself. I think it’s more likely though that they were pressed by his wife Winifred. She was a very gifted botanist, and set up the first Botany department at the University of Otago in 1919, but gave up her promising career to care for Aitken and their two children. Possibly the flowers were grown in the garden of their last house on Primrosebank Road, or were a gift from a friend during Aitken’s illness. We’ll probably never know, but the flowers are a wonderful and unexpected discovery amongst a fascinating collection.”