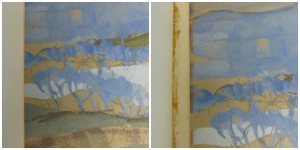

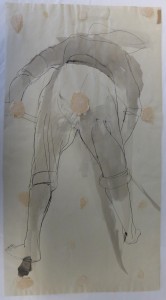

This week, conservation went global – in a very literal sense. Our task: to package and transport sections of a wooden globe, no mean feat considering the globe in question was nearly 1.5 metres in width.

This globe is one of two made by Jacques Elisée Reclus, a French geographer, both of which are held in the Patrick Geddes collection. In 1895, with the support of Alfred Russel Wallace and Patrick Geddes, Reclus proposed the construction of a huge relief globe approximately 420 feet in diameter, but this was never realised.

Geddes’ proposed Institute of Geography in Edinburgh was to incorporate the Reclus globe within it. We think the two globes we have here, which came from the Outlook Tower and were made for Geddes by Reclus, may have been models made for that project.

These globes, now in sections, were required to be packed for storage and transported to a new location (luckily for us, still in the same building!). For this purpose, it is important to choose appropriate housing methods and materials as this will act as a good preventive measure, helping to ensure the long-term preservation of the object. As well providing physical support for items, suitable storage will have the added benefits of providing an extra layer of protection from accidental damage during handling and transportation. It will also act as a buffer to atmospheric pollutants, dust, and light, and guard against any fluctuations in environmental conditions. Appropriate packaging will also come into its own if there was ever to be a flood or water ingress, acting as a barrier and thus protecting the contents from more serious damage.

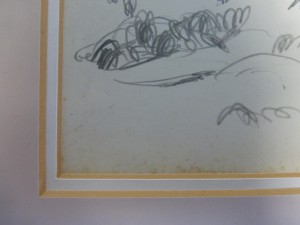

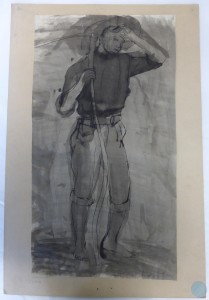

Due to its weight and size, boxing the first globe was not an option. It was decided therefore to soft-wrap its individual sections, using acid-free tissue paper and bubble-wrap. Bubble-wrap was used to provide protective cushioning to the item but it is important that it is used correctly (yes, there is a right and wrong way to use bubble-wrap!). In most cases, it is recommended that the ‘bubbles’ face away from the object – this reduces the risk of creating indentations or marks up the item, particularly if the surface or media is vulnerable, friable or has surface dirt. It is not recommended, however, for bubble-wrap to be placed in direct contact with an object as it is not a recognised conservation-grade material.

Acid-free tissue was therefore used as an interleaving layer between the surface of the globe sections and the bubble-wrap. As the name suggests, it is acid-free and thus a material that we use often, whether for interleaving, wrapping and cushioning objects or padding out excess space in the form of tissue ‘puffs’ or ‘sausages’.

Once safely packaged, we were able to move the globe sections into one of our environmental controlled stores. This will ensure that the temperature and relative humidity conditions are kept stable, and protect against any global warming….

Post by Emma Davey, Conservation Officer