By Vanessa Johnson, conservation trainee and armchair physicist

Well, it’s been six weeks and I’ve survived! Although if archives could kill, the repository of world knowledge would go untapped and we’d be living lives of stone-age simplicity and struggle. Fortunately, archives are relatively harmless and very interesting! They’ve been especially so given their almost unlimited capacity for dirt and equally terrible capacity for retaining said dirt when faced with a tool as effective as a chemical sponge. Upon arriving at the University of Edinburgh’s conservation department for my 6-week placement, I was assigned the task of cleaning and rehousing correspondence from the archives dating from the 1930’s and 1940’s. The task was large but I was up to it! Using the previously mentioned chemical sponges, I wiped away surface dirt and placed the letters in new folders and boxes that were acid-free and sure to preserve them for future use. The old boxes had been rather ill-suited to the task and were glad to be relieved of the burden of keeping so many letters safe.

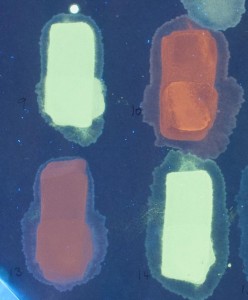

Library correspondence was originally housed in these beauties. Observe the sooty border along the bottom edge of the orange sheet. The clean area was protected by library correspondence.

Letters were cleaned and rehoused in nice grey, acid-free folders and then in archival boxes. I think they will be much happier there.

My duties extended beyond rehousing archival materials, though. In the second week, a University Club of London event was hosted at Holyrood Palace and a display of past menus was requested. These menus were from their archive held by The University of Edinburgh, retained from such distant times as 1878 and 1913, years whose existence can be verified largely through such archival relics. I mounted the menus on a board with labels and sent it off to Holyrood to be admired by the guests. I assume this is exactly what happened as I was not informed of any serious disappointment on anyone’s part regarding my attempts. Whew!

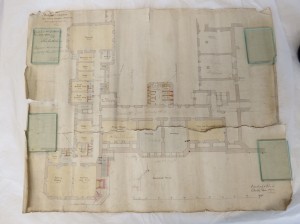

While I plugged away at my correspondence rehousing, a huge box arrived full of damaged architectural plans! My favourite! I do have a soft spot for repairing maps and architectural plans, as they are often very well-made and beautiful. The first step was to create condition reports and treatment proposals for all 56 plans. I had learned to write these in my course at Northumbria University, though they were often 10+ pages and full of information gathered by photographing pieces in the dark with only UV lights on. This was highly impractical for the current project, so I created a spreadsheet with every piece listed, a lettering system for conditions (A – pretty good!, B – Some tears, not too bad, C – Emergency intervention needed! Something to that effect…) and included treatment recommendations in my lettering system. This meant that it took MUCH less time to plan my attack.

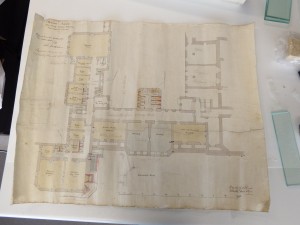

Once this was done, it was time to bring these plans back to life! I started with a C, something that was extremely dirty and had a tear going almost all the way across. Though it took ages, I finished the repair in the few days. I soon developed a system of overlapping tasks, repairing tears while simultaneously surface cleaning a piece. There’s a lot of waiting when repairing tears, so this worked out well. In a little over a week, I was able to complete 5 plans.

Plan before any treatment. The giant rip made the plan a bit difficult to handle, as did the profusion of surface dirt.

Plan after treatment. What was once torn asunder is made whole again!

So many plans with so many problems! Some were in pieces, some had large, degraded holes in them, while others were just extremely dirty. Regardless! They were all treated and brought up to a level of stability and usability. After treating them, I rolled them together with interleaving sheets of acid-free tissue and stored them in an archival box. A label was placed on the outside of the box and the treatment was complete!

I was back to my correspondence and plugging along when what should happen but a textile rehousing workshop! While I’m primarily a paper conservator, I have every interest in rounding out my skills and learning whatever I can about all aspects of conservation. Plus, this workshop seemed to deal with folder making, which, as a paper conservator, I felt particularly able to do. Little did I know that these folders were very time consuming to make! Tuula Pardoe, a textile conservator from the Scottish Conservation Studio at Hopetoun House, wowed us by showing us these beautiful, elegant folders with padded cloth interiors which would hold onto and protect any textiles in the folder. They were gorgeous and I needed to make one! The rest of the day was spent cutting board, ironing fabric and padding the interior of my custom-made folder which would house a textile from the library’s collection. It was tough but the results were worth it and Tuula was a great teacher.

The textile! I chose this one because of its gorgeous, rectangular shape. It seemed well-suited to a folder.

After a day spent slaving away, my folder is nearly done! After that central linen tape dries, I can consider my rehousing project complete!

After folder making, I realized the clock was ticking. I had lots and lots of writing to do and not much time left to do it! In addition to an environmental monitoring report I had been requested to write, I had a blog post to write, a science fair booth to plan, a power point to prepare and photos to sort out! Gah! The environmental monitoring report was almost done, thankfully, and involved analysing data from an exhibit space. Certain materials have a tendency to leave the physical plane when exposed to conditions which are not within an acceptable range, so it was vitally important that the space did not fall outside of that range. We don’t want to lose archival materials to the environment! Nature is truly a harsh mistress.

Conservation is hilarious! But serious. Laughter is the best medicine for accidentally tearing your mock-up, and then repairing it like a pro.

In the midst of this writing bonanza, a teaching opportunity came out of nowhere and set itself up right in the conservation studio! Well, I suppose I’d known about it for some time, but in the hectic last week of work, it did come at a very busy time. Like all things potentially stressful, this day, which was a conservation taster day, proved to be fun instead! Emma, Emily and I taught some eager volunteers about the joys and pitfalls of the world of conservation. They were introduced to ethical issues, conservation techniques, and had questions answered such as ‘Why do conservators work so hard to prevent nature from getting closer to paper?’ Bugs, that’s why. The studio was a mess and we all had a good time repairing mock-ups that were surprisingly difficult to clean (sorry, volunteers) and very easy to tear (sorry, volunteers). They made a great job of it anyway and hopefully left feeling like they understood this strange world of paper conservation.

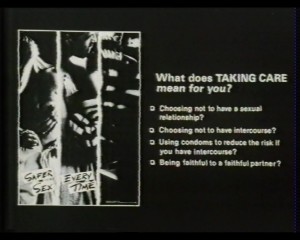

Finally, after all is done, it’s time to plan for the Midlothian Science Fair, a lovely place where families learn how science fits snugly into many, many professions. I was gifted the task of preparing a booth that was clear and relatable yet not so technical that it would alienate people. Well….this was tough. I LOOOVE getting real in-depth in my science explorations so I had to come up with something that a non-nerd would really enjoy. If Bill Nye is any indication, that sort of fun-for-the-family, completely relatable science is practically everywhere and I found just such a science concept in the technical examination of paper. That sounds horrible, I know, but stick with me!

If you’ve ever been around an ultraviolet light, you know that sometimes your white t-shirt glows or your Day-Glo nail polish. Well, conservators, in our wisdom, will sometimes place pieces of art with unknown pigments in just such a light to see what glows and what does not. Depending on what we see, we can usually come to a conclusion about what a pigment is made of (or at least narrow down the possibilities a bit). This gave me the idea for my science fair booth! Kids could make art, look at it in UV (with protective goggles! I ain’t no slouch about the ol’ H&S) and learn a little about chemistry and physics! Hurrah!

So! Idea is in hand, planning plugging along, all is well! I must say, the past 6 weeks have been busy! After everything though, I’m left feeling happy to have had such a wide range of experiences and a bit sad that I can’t finish rehousing all that correspondence. There really is a lot! Hopefully a future conservator can pick up where I left off and learn to love the archive too.