Last Friday, I attended a one-day training workshop on iron gall ink repairs. The session was organised by the Collections Care Team at the National Library of Scotland and hosted by Eliza Jacobi and Claire Phan Tan Luu (Freelance Conservators from the Netherlands and experts in this field. Please see www.practice-in-conservation.com for further information).

Iron gall ink was the standard writing and drawing ink in Europe from the 5th century to the 19th century, and was still used in the 20th century. However, iron gall ink is unstable and can corrode over time, resulting in a weakening of the paper sheet and the formation of cracks and holes. This leads to a loss of legibility, material and physical integrity.

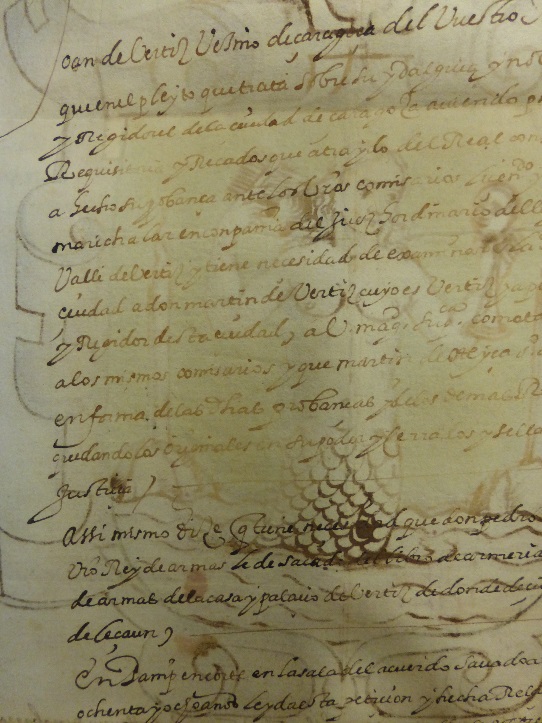

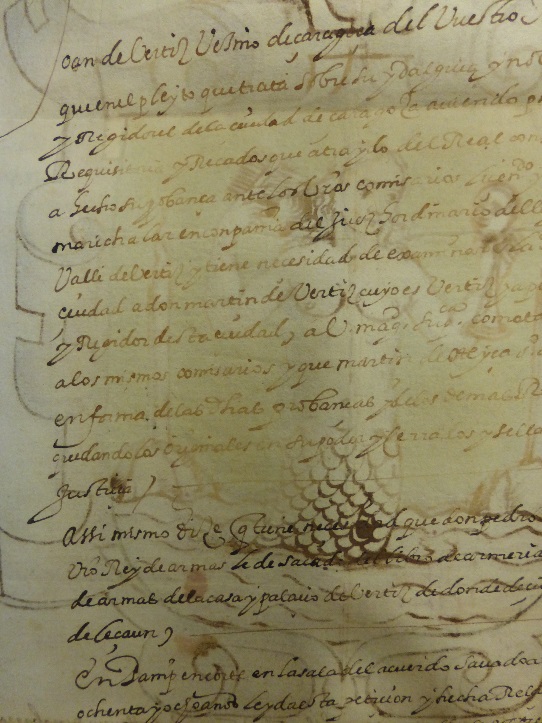

Document in the Laing collection showing early stages of iron gall ink corrosion.

Unsafe handling can exacerbate this problem. Bending and flexing a paper with iron gall ink can cause mechanical stress and result in cracking of the ink and tearing of the sheet. If this has happened, the area needs to be stabilised with a repair to ensure that further tearing doesn’t occur and additional material isn’t lost.

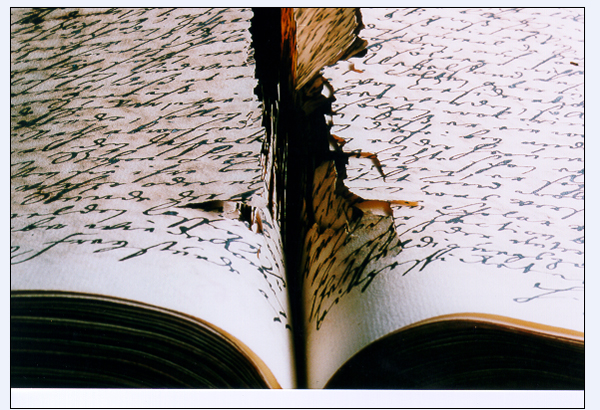

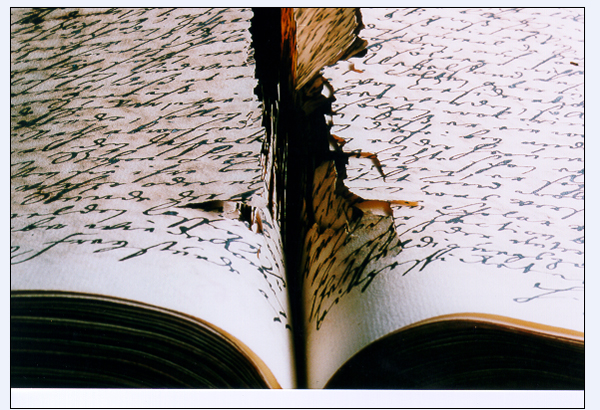

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Books with corroded iron gall ink causing the paper sheet to break.

Paper conservators usually carry out tear repairs with water-based adhesives such as wheat starch paste and Japanese paper. However, this can be harmful for paper with iron gall ink inscriptions. Iron gall ink contains highly water-soluble iron (II) ions. These are invisible, but in contact with water they catalyse the chemical reactions that cause paper to decay. If these ions are not removed before treatment, any introduction of water can cause significant damage to the item. If a tear over an iron gall ink inscription is repaired using an aqueous adhesive, these invisible components will migrate out of the ink into the paper in the surrounding area, and speed up degradation in this location. Since this is not immediately visible, it can take approximately 25 years before the damage is noticeable.

Conservators have only recently become aware of this problem, and have had to develop a method of creating a very dry repair, and a way to test it before application. This is what we were shown during the workshop. First, we created remoistenable tissues for a repair paper using gelatine, rather than the traditional wheat starch paste. Gelatine is used because it has been found to have a positive effect on iron gall ink. It has been suggested that gelatine may inhibit iron gall ink corrosion, however, this has not been proved by empirical research.

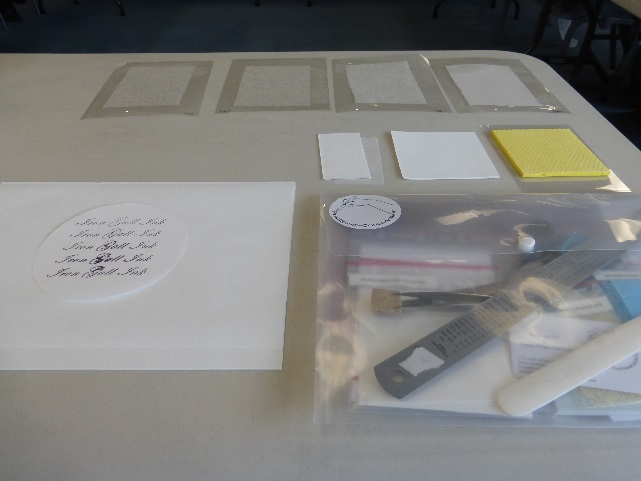

To make the remoistenable tissue, we applied a 3% liquid gelatine solution to a sheet of polyester through a mesh. The mesh ensures that an even layer of gelatine is applied to the sheet. Japanese paper is then laid onto this sheet and left to dry. We created three sheets using different weights of Japanese paper, for use on different types of objects.

Eliza creating a remoistenable tissue.

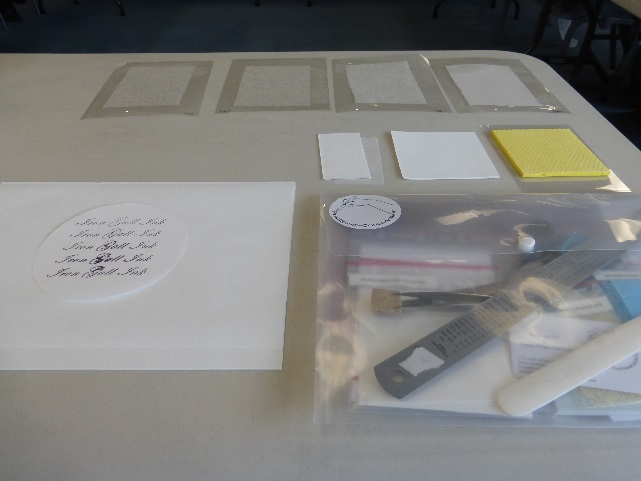

When this was dry we had to remoisten the tissue so that it could be used to fix tears over iron gall ink. We were given a personalised mock-up item to practise this on. To remoisten the tissue, we used a sponge covered with filter paper to ensure that only a minimal amount of water is absorbed. You need just enough to make the gelatine tacky, but not so much that the water will spread away from the repair. Two sheets of filter paper are placed over a thin sponge and just enough water is added to saturate it. A small piece of remoistenable tissue is cut from the pre-prepared sheet, and placed, adhesive side down, on to the paper for a few seconds. This is then lifted using a pair of tweezers and applied to a test piece of paper that has been impregnated with bathophenanthroline and stamped with iron gall ink.

Workstation with four sheets of remoistenable tissue, sponge, filter paper and indicator paper.

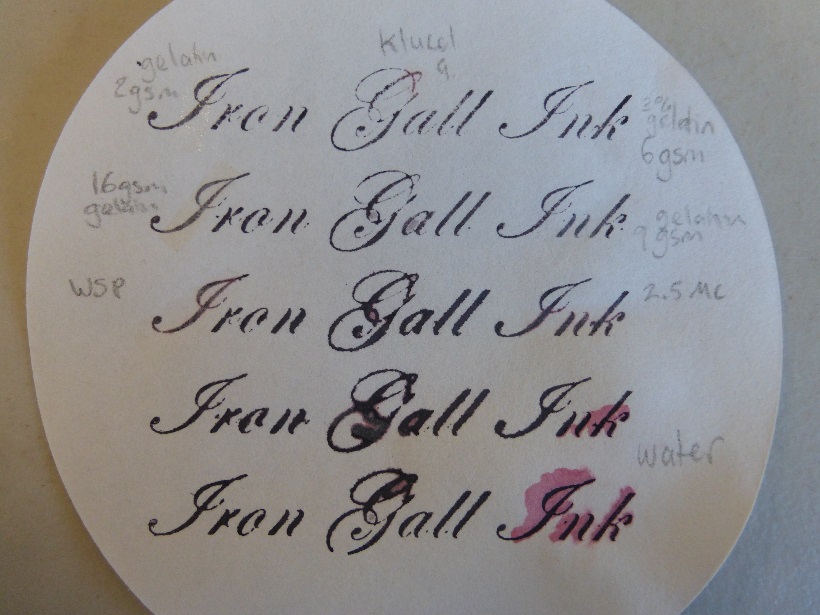

Bathophenanthroline has no colour, but in the presence of iron (II) ions, it turns an intense magenta colour. As such, this sheet can be used as an indicator for the soluble iron (II) ions that can cause paper to degrade. If little or no magenta colour shows after application of the remoistenable tissue, this suggests that the repair paper has the correct moisture level and this method can be used on the real object. We used this indicator paper to try out a range of adhesives, to see what effect they had on the iron gall ink.

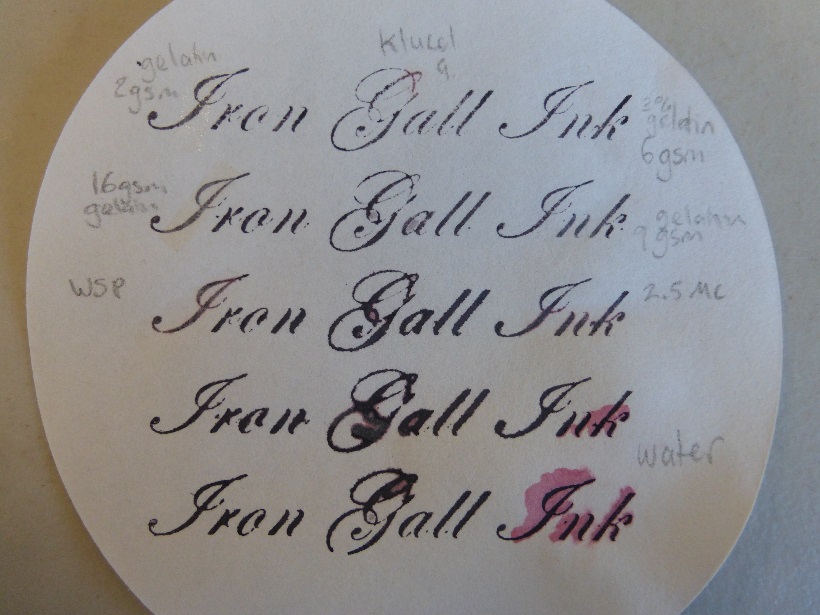

Bathophenanthroline Indicator Paper.

As you can see from the above image, the gelatine remoistenable tissue resulted in limited movement of iron (II) ions, whereas the wheat starch paste (WSP), methylcellulose (MC) and water applied directly to the paper has caused further movement. I thought that this was an excellent method of testing the repair technique, as it rendered the invisible movement of iron (II) ions visible. This means that a Conservator can be sure that the tear repair isn’t causing additional damage to the document.

Overall, the workshop was very informative and useful. A large number of documents at the CRC contain iron gall ink, so I’m sure I will put this new learning into practice very soon!

Check out this website for more information on iron gall ink: http://irongallink.org/igi_index.html

Emily Hick

Project Conservator

The slide show below shows the stages of taking the belt out of the box.

The slide show below shows the stages of taking the belt out of the box.