In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed as part of the conservation team’s ongoing work to make exhibitions at the University of Edinburgh more sustainable.

Tag Archives: Centre for Research Collections

Books, Boxes and Bugs! A day in the life of a Collections Care Technician at the Centre for Research Collections

Welcome to our new Day in the Life Series! The Conservation and Collections Management team recently recruited three new members of staff. In this series each of our new team members will give you an insight into life behind the scenes at The University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections. In this post, our new Collections Care Technician Robyn Rogers discusses what she has been up to since joining the team in March. Expect two more posts in this series, as we introduce our Appraisal Archivist and Archives Collection Manager, Abbie Hartley, and our Collections Management Technician, Jasmine Hide.

My first three months at the Centre for Research Collections have been jam packed – I have installed an exhibition, couriered a loan to the V&A Dundee, cleaned one hundred linear metres of rare books, and rehoused over seventy collection items – and that’s just a small selection of what I’ve been up to! On an average day you might find me jet setting across campus to move a harpsichord at St Cecilia’s Hall, or vising our offsite repository, the University Collections Facility, to clean some especially dirty books, before finishing the day in the Conservation Studio making some phase boxes. I feel fortunate to have worked with many fascinating collection items so far, from a Bible that had been rescued after falling down a well, to 60s pop stars’ microphone of choice. This demonstrates what I love about being a Technician working in cultural heritage – our work focuses on preventative collections care, as opposed to interventive treatment, allowing us to work with an exciting breadth of collections material.

Righting Letters – Conserving the Lyell Collection

Today we have the first installment of a two-part series from Sarah MacLean. Sarah is here on an 8-week internship funded by the NMCT to help with the conservation of the collection of Sir Charles Lyell (1797 – 1875).

As my career in conservation progresses, I find myself drawn most to objects and collections that give insight into the more personal, human aspects of history and heritage. Kings and Queens and famous faces are all very well but I’m more interested in the lives of everyday people – in their passions and machinations, and in how they interacted with the world around them.

Throughout my studies and previous work, I have had ample opportunity to see and conserve this kind of history. Most recently, I worked on the conservation and digitisation of the 1921 Census of England and Wales where I saw first-hand the lives of ordinary people, a snapshot of the nation captured in a single day. And now, as an intern working on the Sir Charles Lyell Collection, I see similar opportunities to preserve and elevate the more unique and personal aspects of the great man’s life.

Sir Charles Lyell (1797 – 1875) was a Scottish geologist and scholar whose discoveries informed a significant shift in our understanding of the Earth and its history. Lyell posited that the geological processes that shaped the Earth are still active in the modern era and through extensive fieldwork, travel, popular lectures, and his best-selling books, he became internationally famous and respected by many scientific communities.

He also corresponded with near-innumerable members of these communities with professional and personal relationships often spanning the entirety of his career in the same way that his precious notebooks do. It is this varied and extensive correspondence that I have been working steadily to conserve and rehouse during my time at the Centre for Research Collections.

A letter from Lyell’s correspondence before and after conservation treatment

This part of the Lyell Collection comprises 22 boxes containing thousands of letters and other documents. Typically, I assess and conserve 1-2 boxes in an average working day and so anticipate completing this work by my 6th week here at the CRC. I re-label each folder of correspondence individually before assessing and conserving its contents as needed. Typically, this work extends to flattening folds and plane distortions, surface cleaning using chemical sponge, undertaking tear repairs, and infilling small lacunae using Remoistenable Tissue (lightweight Japanese paper impregnated with an adhesive that is reactivated with moisture).

My work on the 1921 Census prepared me well for my work on the Lyell correspondence – not only have I built considerable aptitude with my chosen repair material, but I also greatly enjoy the nitty-gritty remedial nature and consistency of the work. However, this consistency and regularity is not to say that the Lyell correspondence has not already yielded some wonderful surprises.

Often, these surprises have come in the form of unique drawings, maps, and other larger format works coloured with an array of aesthetically pleasing pigments. From the coastline of Louisiana to coal deposits in the Scottish Highlands, these works have the potential to tell us not only about Lyell’s working processes and the areas of study he thought most important, but to give greater insight into his personal quirks alongside those of the people with whom he corresponded.

A small drawing showing an erupting volcano illustrating Lyell’s interest in volcanology.

These larger works often pose interesting conservation challenges too. Their scale means that they have been folded to fit their envelopes or other housings and the mechanical stresses this puts on the paper has led in many places to weakness and tears. The repairs that I undertake must not only be neat and visually pleasing but must also be robust enough to withstand handling and consultation as well as the object itself being carefully folded again and returned to its housing.

I have also had the opportunity already during my time at the CRC to tackle Lyell’s collection of geological specimens and discovered a heretofore unknown little example of such a specimen within his correspondence – another pleasant surprise.

Crumpled within a small envelope, I have been unable yet to discover what type of stone these pieces are comprised, but I have been able to rehouse them, encapsulating them in Melinex for the time being so that they can be viewed and consulted without the need for direct handling.

Two small geological samples discovered within an envelope in Lyell’s correspondence.

All the work I have undertaken thus far on the Lyell correspondence has been done with that knowledge that the collection is, at its core, is to be used and learned from. This need for accessibility interests me just as much as the unique and personal stories within Lyell’s correspondence because I believe strongly that the more accessible we are able to make the Lyell Collection and others like it, the greater the impetus will be for such treasures to be preserved and protected in the future.

Interactive Integrated Pest Management

The final post from Sophie Lawson, our conservation Employ.ed intern, in this week’s blog…

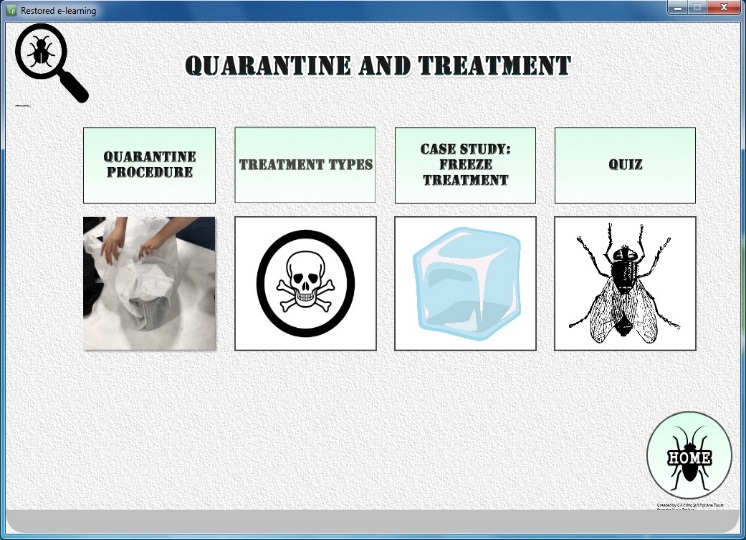

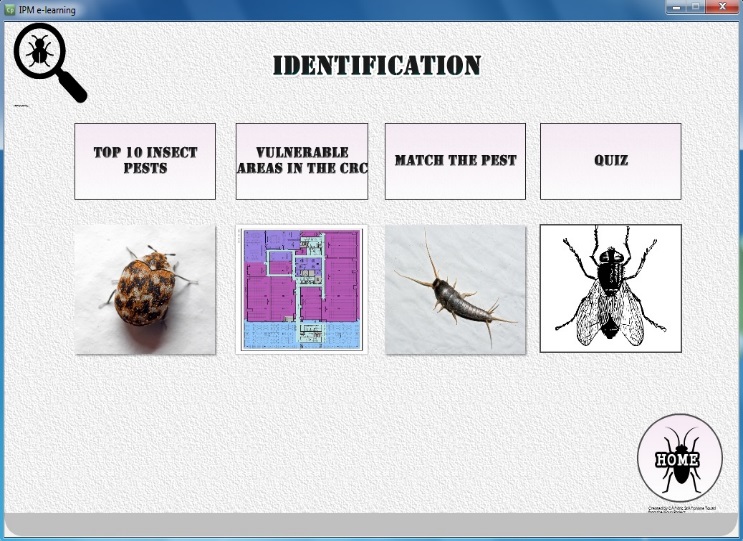

We are approaching the end of our Conservation E-learning project, with a completed trial resource being prepared to go to our first focus group. The resource focuses on providing the user with an introductory level of knowledge of Integrated Pest Management, with a focus on the problem of insect pests in Special Collections storage. More specifically, the resource aims to provide a wider knowledge of the following: an introduction to Integrated Pest Management (or IPM), how an IPM plan is implemented, pest identification procedures and the quarantine and treatment procedures within an institution.

The interactive menu-based home screen of the trial e-learning resource

Quarantine and Treatment clickable menu screen

Identification clickable menu screen

A Fond Farewell

For the last ten weeks I have been working with Project Conservator, Emily Hick to conserve and rehouse a collection of rare Greek books. The weeks have gone racing by and now my internship has come to an end. In light of this, I would like to share a bit more about my internship experience at the Centre for Research Collections.

Working on the Blackie project with Emily has been a great way to gain insight into the planning and management of conservation projects. One of my responsibilities as intern was to record the time it took me to complete each task and the materials I used in the process. This was a really useful exercise as it made me think of how I could work more efficiently and be more resourceful with materials. I now feel that I am better equipped to plan and manage conservation projects myself in the future.

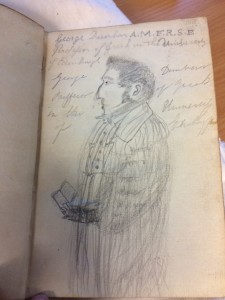

One of the great advantages of working on a project involving Greek books is that I can’t stop and read them! However, I have occasionally found some quirky things in the collections to distract me. My favourite by far is this doodle on the endpaper of an eighteenth century book. The image is of George Dunbar, professor of Greek at Edinburgh University from 1807 to 1851. It looks as if it may have been drawn by one of his students!?

Sketch of George Dunbar, Professor of Greek at Edinburgh University from 1807 -1851

My background is in Preventive Conservation so the internship has been an excellent opportunity to become more familiar with paper conservation. I have been able to learn a lot more about the interventive treatments of paper just by observing Emily and the other conservators at work. As most cultural heritage collections contain paper objects and books, the value of this knowledge cannot be understated. I thoroughly enjoyed having a go at some basic interventive conservation treatments during a Conservation Taster Day held at the CRC, where I learned to do tear repairs and infills on de-accessioned documents.

Having fun making tear repairs during the conservation taster day

As a Preventive Conservator, I feel it is important to have a broad understanding of all materials and objects found in cultural heritage collections. Therefore, it has been particularly helpful for me to visit different parts of the University’s collections to learn how they are cared for. I have been able to visit the Musical Instrument Collections, the Anatomy Museum and the Art Collections. I was fascinated to learn about the treatments and techniques employed in the conservation of musical instruments. During my visit to the anatomy museum I was interested to learn about the practical ethical challenges in caring for collections of human remains.

Musical instrument conservation studio

Throughout the internship I have had access to training, which has significantly improved my knowledge and skills in both preventive and remedial conservation. I have received training on rehousing, disaster planning and designing collections databases. The training will undoubtedly improve my chances of finding employment once the internship concludes. I have also been able to get an idea of what is involved in running a staff training day by assisting Emma Davey, Conservation Officer, in preparing for the disaster response and salvage training.

Learning to make temporary boxes for books

Building wind tunnels during salvage training

I have thoroughly enjoyed my time working with the Conservation Department at the CRC. I have been encouraged to get involved in all aspects of the Department’s work, from conservation and collections care, to public engagement activities. As a new graduate, the internship has allowed me to put the knowledge gained from my Masters degree into practice and given me more confidence in my abilities. The conservation team have all been very supportive and have given me lots great advice on career development. All in all, I think an internship with the CRC is an excellent opportunity for a new graduate, and I would strongly recommend it to anyone starting out in conservation.