In this week’s blog we hear from Musical Instrument Museums Edinburgh (MIMEd) Conservator, Jonathan Santa Maria Bouquet, who recently attended a training workshop on wood identification in Norway.

Jonathan examining wood samples

In this week’s blog we hear from Musical Instrument Museums Edinburgh (MIMEd) Conservator, Jonathan Santa Maria Bouquet, who recently attended a training workshop on wood identification in Norway.

Jonathan examining wood samples

Rehousing is a key part of conservation. But why is it so important? Find out in this week’s blog from Special Collections Conservator, Emily…

We recently received a large number of drop spine boxes to house the Laing Western manuscript collection. This was a part of a month-long project to conserve this collection, which you can read more about by following this link. These boxes are handmade to match the exact dimensions of the book. Not only do they look great on the shelves, they also provide excellent protection for the books. However, they are relatively expensive and time consuming to make. So the creation of these boxes is often outsourced, and reserved for our most important collections.

Laing manuscript collection, before rehousing

Laing manuscript collection, after rehousing

In this week’s blog we hear from Anna O’Regan, who recently attended a Conservation Taster Day at the CRC. Anna discusses why she wanted to take part, and what she learnt during the day…

My educational background is in Museum Studies and Cultural Heritage. While I enjoyed studying this masters degree, I found it to be a little too broad, and although I did choose to narrow the focus to cataloguing and gained voluntary experience in this area, I felt like this wasn’t the right path for me to follow. Then I stumbled upon conservation and figured out which direction I want to proceed in. When I learned about the Conservation Taster Day at Edinburgh University I was thrilled to be invited to take part and learn more about what branches of conservation there are, so I could get the information I needed and make a decision about what precisely I want to specialise in. Having completed the day I can say with certainty that paper conservation is for me and I couldn’t be more excited for what the future holds.

In this week’s blog Project Conservator, Katharine Richardson, discusses the challenges she has faced while reviewing the CRC’s Disaster Plan….

For the last two months I have been reviewing the Disaster Response and Recovery Plan for the University of Edinburgh’s rare and unique collections. The plan covers twelve different collection sites across the University campus that contain a large number of diverse objects and materials, including archives, anatomical specimens and musical instruments.

One of the most challenging aspects of the project has been to identify each collection’s vulnerabilities and to anticipate the risks involved in moving and handling them during a disaster response operation. Some collection items have very specific handling requirements which must be recorded in the plan, such as the School of Scottish Studies Archive’s audio visual equipment that is so sensitive to movement that they can be damaged beyond repair from one slight knock. There are also certain collections that contain items hazardous to human health, one example being the geology collections, which contain specimens of mercury and asbestos. These, too, require specialist handling instructions and a record of what personal protective equipment (PPE) is required.

I was recently asked to rehouse a new accession to the CRC special collections; a beautiful belt previously belonging to a Scottish Suffragette made from a strip of ribbon, embroidered with enamelled motifs, with a metal buckle. You can find out more about this belt in this blog post.

Suffragette Belt

Due to the huge amount of attention this item received on social media, I knew that it would be very popular, and likely to be requested multiple times for seminars, tours and researchers. As such, I wanted to create a housing solution that would reduce the handling of this item, as well as protect it whilst in storage.

Repeated handling can be very damaging to objects as the bending and flexing causes mechanical stress, which can lead to fractures at stress points. It is often assumed that white cotton gloves are worn when moving all archival collections. But that is not the case. Cotton gloves tend to reduce manual dexterity, and can get caught on tears on paper. Here is an excellent article on the misperceptions of wearing white gloves.

Handling certain objects, such as gilt frames, photographs and bronze sculptures without gloves, however, can be detrimental as the salts and oils on our fingertips can cause metals in corrode and leave marks on photographs. Normally nitrile gloves are worn when touching these items. Clean, dry hands that are free of creams and lotions are usually the best for most other objects, but ideally they should be handled as little as possible.

To reduce handling of the belt, I made a box with from unbuffered card and two rigid base boards that were padded with domett wadding and calico cotton. One base board can be used to lift out the belt from the box. The other can be placed on top and used to flip the belt over, so that the reverse can be viewed without touching it at all.

The slide show below shows the stages of taking the belt out of the box.

The slide show below shows the stages of taking the belt out of the box.

This new storage will allow the Suffragette belt to be safely consulted for years to come.

Emily Hick

Special Collections Conservator

Last Friday, I attended a one-day training workshop on iron gall ink repairs. The session was organised by the Collections Care Team at the National Library of Scotland and hosted by Eliza Jacobi and Claire Phan Tan Luu (Freelance Conservators from the Netherlands and experts in this field. Please see www.practice-in-conservation.com for further information).

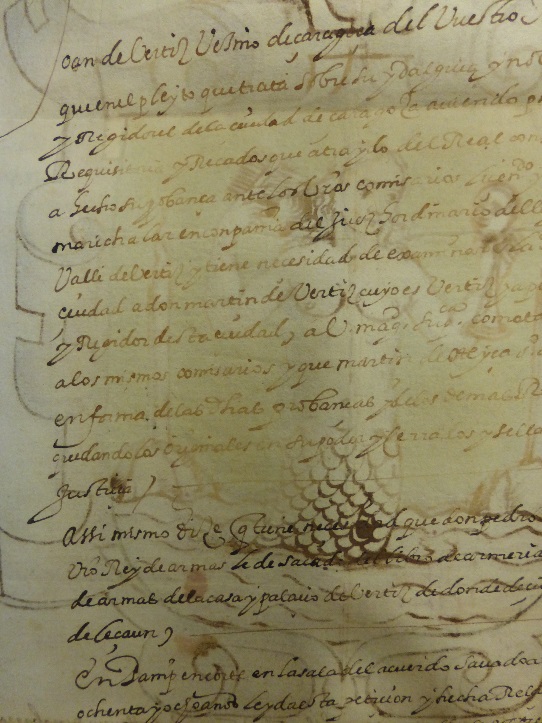

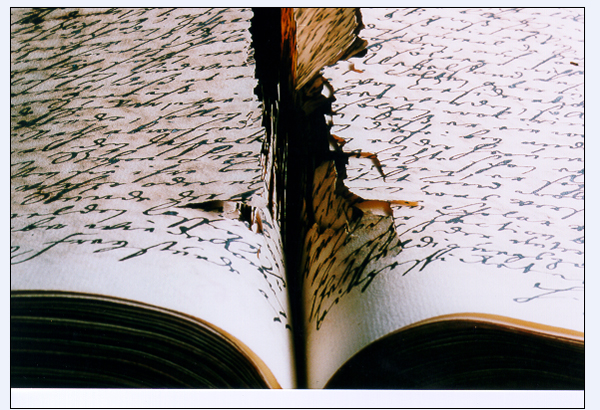

Iron gall ink was the standard writing and drawing ink in Europe from the 5th century to the 19th century, and was still used in the 20th century. However, iron gall ink is unstable and can corrode over time, resulting in a weakening of the paper sheet and the formation of cracks and holes. This leads to a loss of legibility, material and physical integrity.

Document in the Laing collection showing early stages of iron gall ink corrosion.

Unsafe handling can exacerbate this problem. Bending and flexing a paper with iron gall ink can cause mechanical stress and result in cracking of the ink and tearing of the sheet. If this has happened, the area needs to be stabilised with a repair to ensure that further tearing doesn’t occur and additional material isn’t lost.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Books with corroded iron gall ink causing the paper sheet to break.

Paper conservators usually carry out tear repairs with water-based adhesives such as wheat starch paste and Japanese paper. However, this can be harmful for paper with iron gall ink inscriptions. Iron gall ink contains highly water-soluble iron (II) ions. These are invisible, but in contact with water they catalyse the chemical reactions that cause paper to decay. If these ions are not removed before treatment, any introduction of water can cause significant damage to the item. If a tear over an iron gall ink inscription is repaired using an aqueous adhesive, these invisible components will migrate out of the ink into the paper in the surrounding area, and speed up degradation in this location. Since this is not immediately visible, it can take approximately 25 years before the damage is noticeable.

Conservators have only recently become aware of this problem, and have had to develop a method of creating a very dry repair, and a way to test it before application. This is what we were shown during the workshop. First, we created remoistenable tissues for a repair paper using gelatine, rather than the traditional wheat starch paste. Gelatine is used because it has been found to have a positive effect on iron gall ink. It has been suggested that gelatine may inhibit iron gall ink corrosion, however, this has not been proved by empirical research.

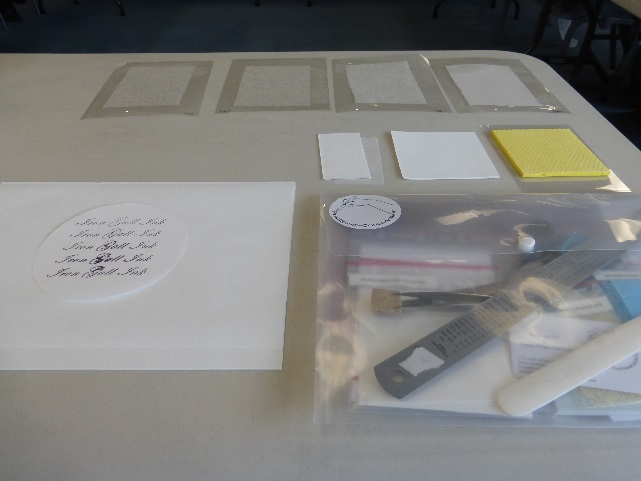

To make the remoistenable tissue, we applied a 3% liquid gelatine solution to a sheet of polyester through a mesh. The mesh ensures that an even layer of gelatine is applied to the sheet. Japanese paper is then laid onto this sheet and left to dry. We created three sheets using different weights of Japanese paper, for use on different types of objects.

Eliza creating a remoistenable tissue.

When this was dry we had to remoisten the tissue so that it could be used to fix tears over iron gall ink. We were given a personalised mock-up item to practise this on. To remoisten the tissue, we used a sponge covered with filter paper to ensure that only a minimal amount of water is absorbed. You need just enough to make the gelatine tacky, but not so much that the water will spread away from the repair. Two sheets of filter paper are placed over a thin sponge and just enough water is added to saturate it. A small piece of remoistenable tissue is cut from the pre-prepared sheet, and placed, adhesive side down, on to the paper for a few seconds. This is then lifted using a pair of tweezers and applied to a test piece of paper that has been impregnated with bathophenanthroline and stamped with iron gall ink.

Workstation with four sheets of remoistenable tissue, sponge, filter paper and indicator paper.

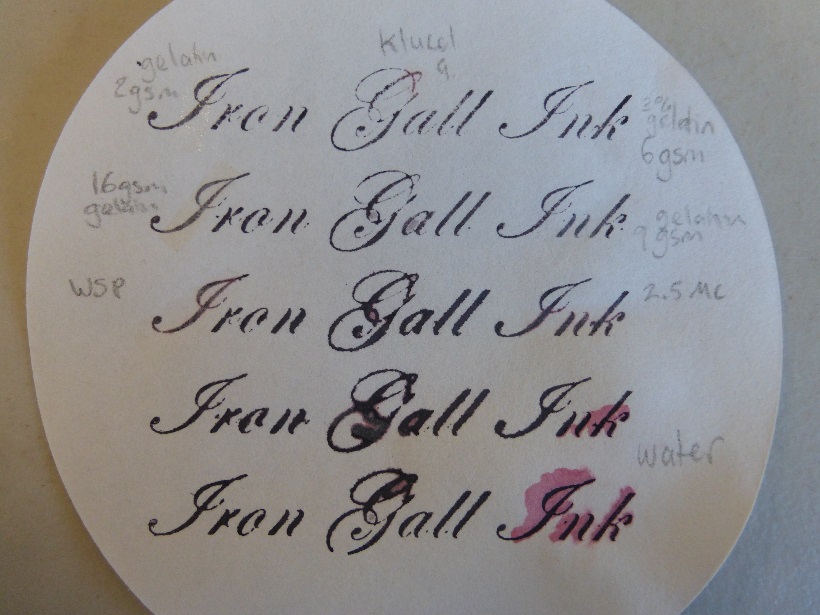

Bathophenanthroline has no colour, but in the presence of iron (II) ions, it turns an intense magenta colour. As such, this sheet can be used as an indicator for the soluble iron (II) ions that can cause paper to degrade. If little or no magenta colour shows after application of the remoistenable tissue, this suggests that the repair paper has the correct moisture level and this method can be used on the real object. We used this indicator paper to try out a range of adhesives, to see what effect they had on the iron gall ink.

Bathophenanthroline Indicator Paper.

As you can see from the above image, the gelatine remoistenable tissue resulted in limited movement of iron (II) ions, whereas the wheat starch paste (WSP), methylcellulose (MC) and water applied directly to the paper has caused further movement. I thought that this was an excellent method of testing the repair technique, as it rendered the invisible movement of iron (II) ions visible. This means that a Conservator can be sure that the tear repair isn’t causing additional damage to the document.

Overall, the workshop was very informative and useful. A large number of documents at the CRC contain iron gall ink, so I’m sure I will put this new learning into practice very soon!

Check out this website for more information on iron gall ink: http://irongallink.org/igi_index.html

Emily Hick

Project Conservator

February saw the start of a new project to surface clean and rehouse the CRC’s most important collection of Western medieval manuscripts, which were bequeathed to the library by David Laing in 1878. His collection contains 121 Western manuscripts, most of which are very finely illuminated or textually important.

Figure 1. Details of illuminations found in the manuscripts

Due to the age and past storage of the material, many items have accumulated a large amount of surface dirt. As well as reducing the aesthetic quality of the manuscripts, surface soiling can potentially be very damaging to paper and parchment artefacts.

Figure 2. Accumulation of surface dirt on a manuscript

Firstly, dirt particulates can have an abrasive action on a microscopic level, causing a weakening of the fibres. Dust can also become acidic due to the absorption of atmospheric pollutants. Sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxides present in the environment, in combination with moisture and the metallic impurities found in dirt, can be converted to sulphuric acid and nitric acid respectively. This is absorbed by the pages and results in a loss of strength and flexibility. Dust can also provide a food source for insects and mould. Mould spores in the air can settle on the manuscripts and live on the organic material in the dust. At a high relative humidity, these moulds can thrive. Surface dirt can also cause staining of the item. Dirt can readily absorb moisture which causes the particulates to sink deeper into the paper or parchment fibres, making it impossible to remove by surface cleaning methods.

Figure 3. Example of ingrained surface dirt on a manuscript

To remove loose particulates, a museum vac is firstly used to quickly hoover up large amounts of dirt. It has adjustable suction levels, so it can be used on fragile items if needed. A range of attachments can be used to reach dirt in all the nooks and crannies of the manuscripts. The museum vac also has filters to prevent any mould spores removed from the book getting back out into the studio.

Figure 4. A museum vac (left) with attachments (right)

A chemical sponge is then used to remove ingrained dirt. This is a block of vulcanised natural rubber which picks up dirt and holds it in its substrate. It was originally developed to remove soot from fire damaged objects.

Figure 5. Using chemical sponge to surface clean a manuscript

Many of the manuscripts pages are extremely cockled. This has resulted in the ingress of dust further into the text block. Due to this, the manuscripts must be examined page by page to ensure all dirt is removed, which can be very time consuming, especially for the larger volumes. However, all the hard work is worth it. Knowing we are making a difference to the condition of the collection, and seeing the change in the books is very satisfying!

Figure 6. Stages of surface cleaning. Before treatment (left), cleaned with museum vac (middle), cleaned with chemical sponge (right)

For the last ten weeks I have been working with Project Conservator, Emily Hick to conserve and rehouse a collection of rare Greek books. The weeks have gone racing by and now my internship has come to an end. In light of this, I would like to share a bit more about my internship experience at the Centre for Research Collections.

Working on the Blackie project with Emily has been a great way to gain insight into the planning and management of conservation projects. One of my responsibilities as intern was to record the time it took me to complete each task and the materials I used in the process. This was a really useful exercise as it made me think of how I could work more efficiently and be more resourceful with materials. I now feel that I am better equipped to plan and manage conservation projects myself in the future.

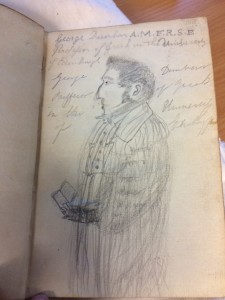

One of the great advantages of working on a project involving Greek books is that I can’t stop and read them! However, I have occasionally found some quirky things in the collections to distract me. My favourite by far is this doodle on the endpaper of an eighteenth century book. The image is of George Dunbar, professor of Greek at Edinburgh University from 1807 to 1851. It looks as if it may have been drawn by one of his students!?

Sketch of George Dunbar, Professor of Greek at Edinburgh University from 1807 -1851

My background is in Preventive Conservation so the internship has been an excellent opportunity to become more familiar with paper conservation. I have been able to learn a lot more about the interventive treatments of paper just by observing Emily and the other conservators at work. As most cultural heritage collections contain paper objects and books, the value of this knowledge cannot be understated. I thoroughly enjoyed having a go at some basic interventive conservation treatments during a Conservation Taster Day held at the CRC, where I learned to do tear repairs and infills on de-accessioned documents.

Having fun making tear repairs during the conservation taster day

As a Preventive Conservator, I feel it is important to have a broad understanding of all materials and objects found in cultural heritage collections. Therefore, it has been particularly helpful for me to visit different parts of the University’s collections to learn how they are cared for. I have been able to visit the Musical Instrument Collections, the Anatomy Museum and the Art Collections. I was fascinated to learn about the treatments and techniques employed in the conservation of musical instruments. During my visit to the anatomy museum I was interested to learn about the practical ethical challenges in caring for collections of human remains.

Musical instrument conservation studio

Throughout the internship I have had access to training, which has significantly improved my knowledge and skills in both preventive and remedial conservation. I have received training on rehousing, disaster planning and designing collections databases. The training will undoubtedly improve my chances of finding employment once the internship concludes. I have also been able to get an idea of what is involved in running a staff training day by assisting Emma Davey, Conservation Officer, in preparing for the disaster response and salvage training.

Learning to make temporary boxes for books

Building wind tunnels during salvage training

I have thoroughly enjoyed my time working with the Conservation Department at the CRC. I have been encouraged to get involved in all aspects of the Department’s work, from conservation and collections care, to public engagement activities. As a new graduate, the internship has allowed me to put the knowledge gained from my Masters degree into practice and given me more confidence in my abilities. The conservation team have all been very supportive and have given me lots great advice on career development. All in all, I think an internship with the CRC is an excellent opportunity for a new graduate, and I would strongly recommend it to anyone starting out in conservation.

In this week’s blog post, we hear from Project Conservator, Emily Hick, who recently carried out a self-led continuing professional development project at the CRC, which was funded by the June Baker Trust Grants for Emerging Conservators….

The June Baker Trust was set up in 1990 to promote and encourage the development and study of the conservation of either historical or artistic artefacts in Scotland. Since that time the scheme has awarded more than £25,000 in grants to Scottish conservators for continuous professional development.

The success of these awards led the trustees to develop a new strand of funding for emerging conservators, which has been made possible this year thanks to the generosity of the Gordon Fraser Charitable Trust.

In May 2015, three newly qualified conservators based in Scotland, received awards of up to £1000 each from the June Baker Trust to carry out a project of their own design, and I was lucky enough to be one of them.

My project focused on developing my skills of carrying out surveys for conservation work. I chose to focus on this area after analysing my CV and finding that this was an area of weakness. It is difficult to gain these types of skills as an emerging conservator as often a project has been scoped out before a position starts. If mistakes are made while surveying a collection, and incorrect time and material estimates are given, it can result in going over budget and over time. So these are vital skills to develop.

The project lasted four weeks in total, and I began by spending a day at Royal Commission of Historic and Ancient Monuments in Scotland (RCHAMS). During this time they were carrying out a survey of their whole collection prior to a merger with Historic Scotland. Due to the limited time available, they had developed a very basic survey to gain condition and current housing data. I helped carry out this survey and was also shown a previous, more detailed survey of the whole collection that had been carried out 5 years beforehand, as well as several other types of surveys they had done in the past.

I also spent two days at the National Library of Scotland (NLS). Here I was shown several surveys in a range of styles; A Preservation Assessment Survey (PAS) of the whole collection using a random sampling method, an item by item survey of the photographic collection, and a basic survey of bound volumes prior to digitisation. The conservators talked about how they change the criteria of the survey depending on how the results would be used, rather than having a ‘one size fits all’ approach, and gave useful tips about what types of questions to include. I also helped to carry out a survey of a collection of printed ballads. I was also shown how to create a Microsoft Access Database to make my own survey form.

Following this, I then spent two days carrying out research on survey methods, spending time at Edinburgh University Library and at the National Library Scotland. I also took a day to create two surveys databases on Microsoft Access Database for use in carrying out two collection reviews at the CRC.

At the CRC, I carried out three surveys in total; an item by item survey of the Oriental Manuscripts collection (5 days), and a random sample survey of the Laing collection (5 days). Following this, I spent two days writing up reports which included information on the condition of the collections, recommendations for future work, materials needed and time estimates. I also spent two days carrying out a brief survey on the use of space in the store rooms, suggesting how items could be repackaged to make more efficient use of the shelving.

This project has been hugely beneficial to me and helped me gain surveying skills which are frequently asked for in more senior conservation job descriptions. I hope that the reports will also be useful to the CRC and inform future funding bids.

Emily Hick, Project Conservator

Hello, my name is Katharine – I’m the new Intern with the Conservation department at the Centre for Research Collections. Having spent the last four years working in collections care in historic houses, I was keen to branch out and experience a different working environment in conservation. I’m thrilled to have been given this opportunity to work with the research collections at Edinburgh University. It has been interesting to learn about the challenges of managing a working research collection and the conservation issues that come with it.

I’m working with Project Conservator, Emily Hick, for 10 weeks, to conserve and rehouse a collection of Greek books owned by John Stuart Blackie, Professor of Greek at Edinburgh University from 1852 to 1882. The collection was largely in poor condition; most of the books were very dusty and had suffered some degree physical damage from years of use and exposure. In this state, many of the books were unable to be used by researchers without suffering further damage. The aim of this project is to stabilise and protect the collection and thus making it accessible to researchers.

The first step of the project was to surface clean the collection. To save time only the edges of the text block and end papers of the books were cleaned, as these are typically the areas where most dust accumulates on books. I started by removing loose surface dirt using a vacuum cleaner with on low suction setting and a soft brush attachment. I then removed the ingrained surface dirt using smoke sponge.

An example of a dusty book before surface cleaning

An example of a dusty book before surface cleaning

As I finished cleaning each shelf of books Emily started the interventive conservation treatments, which has included consolidation of red rot, and re-attaching loose boards and spines.

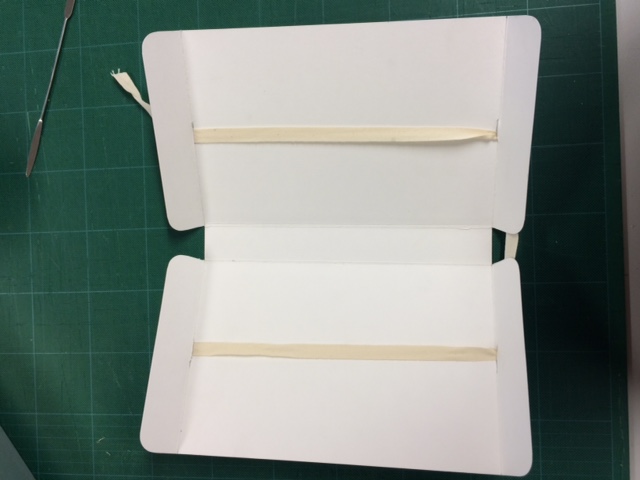

Once the books have received their treatment rehousing can begin. Each book is to be given its own made-to-measure enclosure made of acid-free box board. The book enclosures are a relatively simple design. The box board is cut to fit the book’s shape as closely as possible, folded together and fastened with cotton archival tape. By using this design we avoid using adhesives which release potentially harmful gases that may damage the books.

Finished book enclosure

Finished book enclosure

The enclosures will protect the books from physical damage caused be handling, and in addition will act as a barrier against dust and the environment while the books are in storage.

Books looking happy in their new enclosures

Books looking happy in their new enclosures

Keep an eye out for future posts about this project over the next couple of months!