This week, we say farewell to our conservation intern, Samantha. To mark the end of her 10-week internship working on the Thomson-Walker collection, we put some questions to Samantha to find out more about her time working on the project:

- Why did you decide to apply for the internship at the CRC?

When I graduated last June I decided to make a career plan. This included at least one year of work experience, which would allow me to put my education into practice, strengthen my skills set, and improve areas of weakness. This need to develop had been my main ambition when applying for opportunities. However this particular internship intrigued me for a couple of other reasons. I was interested in the idea of working for a University conservation studio and how this might compare with working for a museum for instance. Inviting also was the prospect of leading a big project during the first phase of conservation; when you train as a conservator it is unusual to work on a large collection independently and so this was an excellent opportunity to do so.

- What did you expect from the internship? Has anything surprised you?

I thought I would be working solely on the Thomson-Walker collection, but I very quickly recognised that this was not the case. I would indeed be occupied with the Thomson-Walker collection on a daily basis, however I would also be giving tours, supervising volunteers, teaching taster days, writing blog posts and assisting with an exhibition, which was a pleasant surprise.

- Tell us about what you’ve learnt over the past 10 weeks.

I now know how to survey a collection and create a project proposal. Creating a programme of conservation and preservation that doesn’t just benefit one print but over 2000 felt very daunting 10 weeks ago. But by taking small steps, and keeping in mind that my approach would have to be interpreted by interns after me I have been able to get through it by staying methodical, and making vigorous notes and to do lists!

- Can you describe for our blog readers a typical day within the CRC conservation studio?

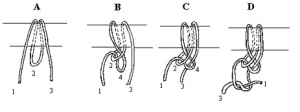

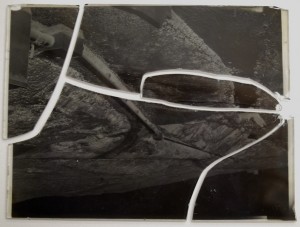

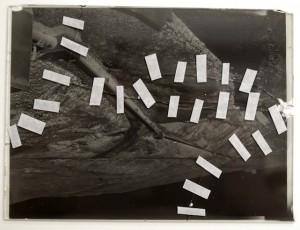

The conservation treatment of the Thomson-Walker collection included removing old backing boards and using a carboxymethyl cellulose poultice to remove tape and adhesive. As this poultice is essential to the treatment I would prepare the CMC the previous evening and construct the poultices as soon as I arrived at the studio the following morning. Once these were ready I began the treatment. Because of the demanding nature of the project, I worked on a number of prints simultaneously, aiming to conserve and rehouse around 10-15 per day. Whilst this is going on I might assist with a tour of the conservation studio, discussing the project with visitors and giving demonstrations. And then during the second half of the day a volunteer would help me to create archival folders to rehouse prints that I’d previously conserved. The CRC has a number of dedicated volunteers, usually students with an interest in conservation wishing to gain experience before embarking upon a relevant degree. This partnership has been very successful for the Thomson-Walker collection, as it has allowed me to conserve more prints, whilst a volunteer has gained new skills and experience.

- What have you enjoyed most about your time with us?

Working within a University. I was unsure how this would compare with my previous experience of working within a museum or archive setting, but the difference has been huge. One of the main objectives of the CRC conservation studio is to make their collection more accessible and fun. I have really embraced this ideology during my time here, and hope to be an advocate of such aims during my future career. Working in such an open and exciting atmosphere has also done wonders for my confidence.

- What have you found most challenging?

Creating a rehousing programme for the Thomson-Walker collection. This wasn’t just difficult because of the sheer number of prints but because they are all completely different sizes! I started out by wrestling with measurements, conservation catalogues, budgets, time restrictions, calculations, and ordering forms. Once this was all worked out I could relax a little. That was until my order arrived…then I had to make sure that all those calculations had been correct and actually get the project underway.

- What shall you miss about the internship?

As an intern, it is not always possible to be self-directed, and projects aimed for interns are typically already set up and ready to go. For this reason I shall miss the independence I have experienced whilst working on the Thomson-Walker collection. I have enjoyed creating and following my own rules.

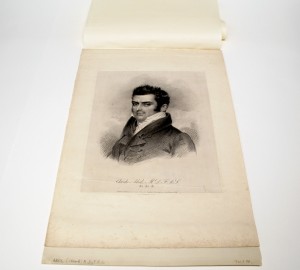

- Do you have a favourite print?

Yes! I recently discovered a print of Dr Albert Isaiah Coffin (1790–1866). Whilst the print itself isn’t spectacular I found the name rather amusing and decided to do some  research on the American herbalist. It turns out that Dr Coffin was a man ahead of his time and has even been called a revolutionary. Instead of paying extortionate fees for a conventional doctor, Dr Coffin advocated that one should learn the secrets of medical botany and be their own doctor. In the north of England, Coffin delivered lectures to working people and set up botany societies where people could meet to learn and discuss medicine, as well as sharing problems and tips. This idea was nicknamed, “coffinism.” In a way I feel that Coffin’s aims are echoed within the CRC conservation studio…well not quite, but we do offer conservation taster days!

research on the American herbalist. It turns out that Dr Coffin was a man ahead of his time and has even been called a revolutionary. Instead of paying extortionate fees for a conventional doctor, Dr Coffin advocated that one should learn the secrets of medical botany and be their own doctor. In the north of England, Coffin delivered lectures to working people and set up botany societies where people could meet to learn and discuss medicine, as well as sharing problems and tips. This idea was nicknamed, “coffinism.” In a way I feel that Coffin’s aims are echoed within the CRC conservation studio…well not quite, but we do offer conservation taster days!

- What advise would you give to the next intern working on the Thomson-Walker collection?

The conservation studio is currently a very exciting place to be working for all of the reasons I’ve mentioned above. Take advantage of all the extra activities on offer. Work hard but play harder!

From all of us in the conservation studio, and the CRC as a whole, we would like to thank Samantha for all her fantastic work, and wish her the best of luck in her future career. In the meantime, we will be sure to keep you updated on how the Thomson-Walker project developments….

Post by Samantha Cawson, Conservation Intern