In this week’s blog post, we hear from Project Conservator, Emily Hick, who recently carried out a self-led continuing professional development project at the CRC, which was funded by the June Baker Trust Grants for Emerging Conservators….

The June Baker Trust was set up in 1990 to promote and encourage the development and study of the conservation of either historical or artistic artefacts in Scotland. Since that time the scheme has awarded more than £25,000 in grants to Scottish conservators for continuous professional development.

The success of these awards led the trustees to develop a new strand of funding for emerging conservators, which has been made possible this year thanks to the generosity of the Gordon Fraser Charitable Trust.

In May 2015, three newly qualified conservators based in Scotland, received awards of up to £1000 each from the June Baker Trust to carry out a project of their own design, and I was lucky enough to be one of them.

My project focused on developing my skills of carrying out surveys for conservation work. I chose to focus on this area after analysing my CV and finding that this was an area of weakness. It is difficult to gain these types of skills as an emerging conservator as often a project has been scoped out before a position starts. If mistakes are made while surveying a collection, and incorrect time and material estimates are given, it can result in going over budget and over time. So these are vital skills to develop.

The project lasted four weeks in total, and I began by spending a day at Royal Commission of Historic and Ancient Monuments in Scotland (RCHAMS). During this time they were carrying out a survey of their whole collection prior to a merger with Historic Scotland. Due to the limited time available, they had developed a very basic survey to gain condition and current housing data. I helped carry out this survey and was also shown a previous, more detailed survey of the whole collection that had been carried out 5 years beforehand, as well as several other types of surveys they had done in the past.

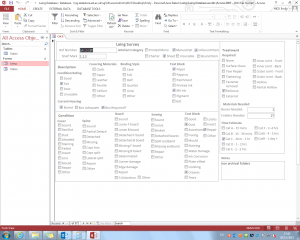

I also spent two days at the National Library of Scotland (NLS). Here I was shown several surveys in a range of styles; A Preservation Assessment Survey (PAS) of the whole collection using a random sampling method, an item by item survey of the photographic collection, and a basic survey of bound volumes prior to digitisation. The conservators talked about how they change the criteria of the survey depending on how the results would be used, rather than having a ‘one size fits all’ approach, and gave useful tips about what types of questions to include. I also helped to carry out a survey of a collection of printed ballads. I was also shown how to create a Microsoft Access Database to make my own survey form.

Following this, I then spent two days carrying out research on survey methods, spending time at Edinburgh University Library and at the National Library Scotland. I also took a day to create two surveys databases on Microsoft Access Database for use in carrying out two collection reviews at the CRC.

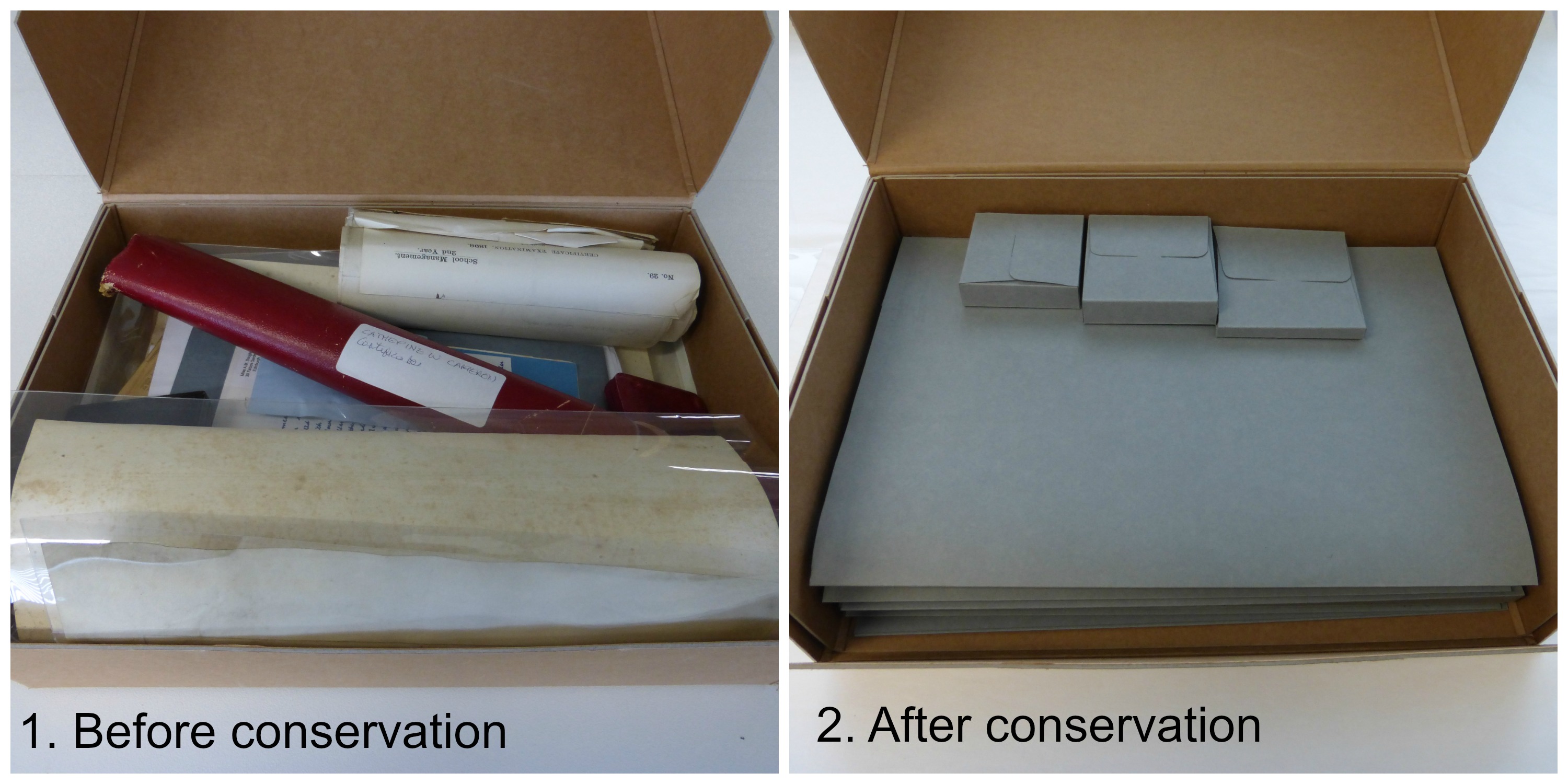

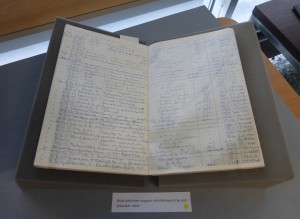

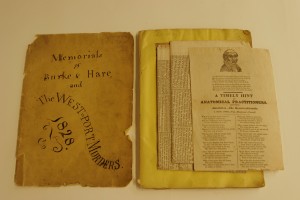

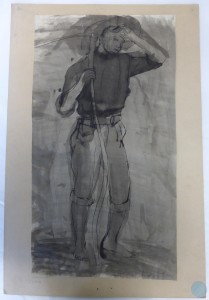

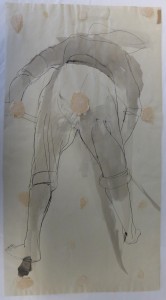

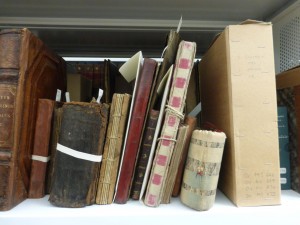

At the CRC, I carried out three surveys in total; an item by item survey of the Oriental Manuscripts collection (5 days), and a random sample survey of the Laing collection (5 days). Following this, I spent two days writing up reports which included information on the condition of the collections, recommendations for future work, materials needed and time estimates. I also spent two days carrying out a brief survey on the use of space in the store rooms, suggesting how items could be repackaged to make more efficient use of the shelving.

This project has been hugely beneficial to me and helped me gain surveying skills which are frequently asked for in more senior conservation job descriptions. I hope that the reports will also be useful to the CRC and inform future funding bids.

Emily Hick, Project Conservator

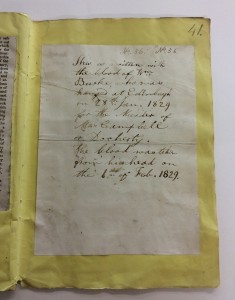

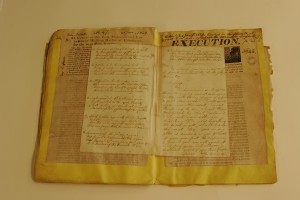

An example of a dusty book before surface cleaning

An example of a dusty book before surface cleaning

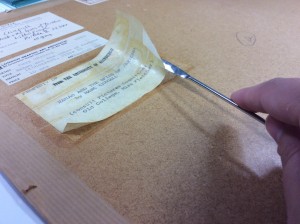

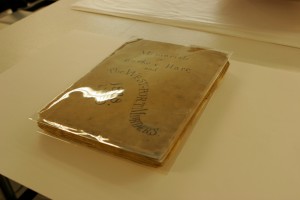

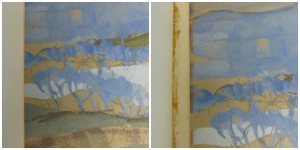

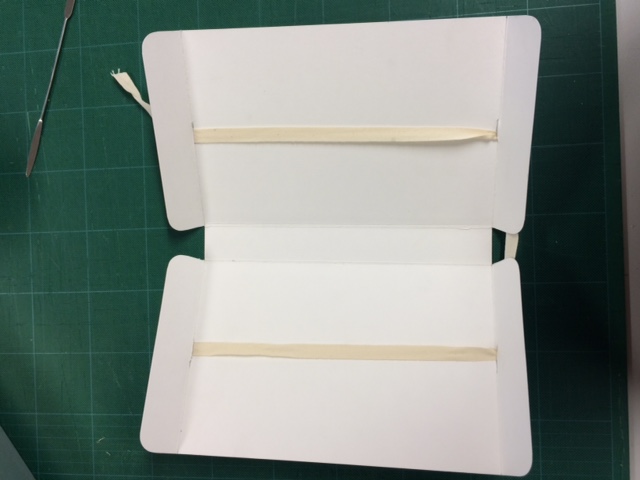

Finished book enclosure

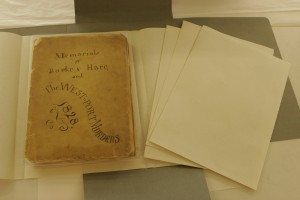

Finished book enclosure  Books looking happy in their new enclosures

Books looking happy in their new enclosures