Last week, a contingent from conservation left their natural habitat of the studio to embark on a day trip up North. Stirling University was our destination, more specifically their conservation studio, in order to learn more about their special collections, and the conservation work they’re doing. Stirling University is currently part way through a Wellcome Trust funded project to conserve and re-house the records from the Royal Scottish National Hospital. Working on this project are conservator Elizabeth Yamada, with interns Kat Saunt and past University of Edinburgh conservation intern Erika Freyr (who you may remember from her work on the Laing project: http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/conservation/2014/06/20/conserving-laing-iii/). We had previously been delighted to have had the chance to show Elizabeth, Kat and Erika our own studio at the Main Library and introduce them to the work we are doing and the collections we hold. We were therefore pleased to have the opportunity pay them a reciprocal visit and learn more about their own project.

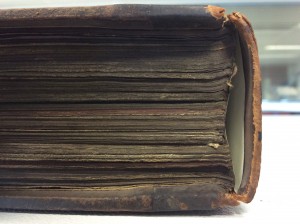

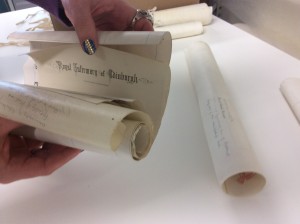

First stop was a visit to their conservation space, and to find out more about the project and their approach to conserving the Hospital’s records. Having converted an old bindery for use as a studio, space was at a premium and with so many records requiring attention, they certainly had their work cut out! The aim of their project is to stabilise the records – through surface cleaning, flattening, tear repair and rehousing – focusing on making them accessible to readers and researchers. It was interesting to learn about how they manage their time, and their thoughts behind deciding what level of treatment they should carry out. It was apparent that time, space and resource constraints made project management so important – something that many people, of all professions, will be able to identify with!

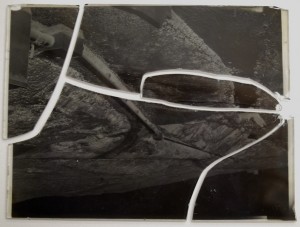

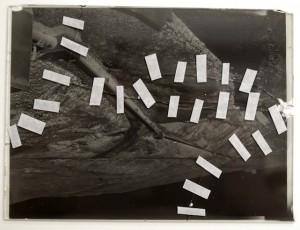

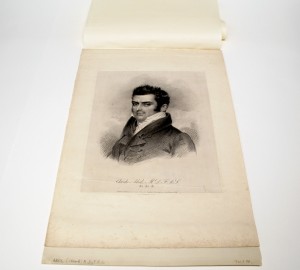

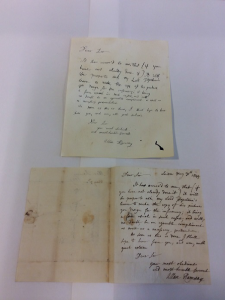

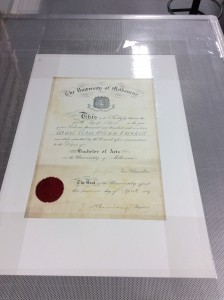

We also had the opportunity to take a closer look at examples from both the University’s wider special collections and those from the Royal Scottish National Hospital. We got a fascinating, and sometimes harrowing, insight into the human stories contained within the archives and, the photographs in particular, gave a glimpse into the daily lives of those that were housed at the hospital.

However, what came as the biggest surprise to us was that, despite not running any History of Art or Fine Art courses, Stirling University has a vast and important art collection with works ranging from paintings by the Scottish Colourist, J.D. Ferguson to a sculpture by Barbara Hepworth. Housed within the Pathfoot Building, there are works by world famous, and home-grown, artists around every corner and in the numerous courtyard spaces. The art collection, and the temporary and permanent exhibitions they hold, are open to the public and I would certainly recommend a visit…

As conservators, we do not work in isolation and visits such as these are important in forging those links with other institutions and to learn how other studios and conservators work. It is a great opportunity to share knowledge and skills thus developing the profession as a whole.

It just leaves me to say big thank you to the conservators at Stirling University for taking the time to show us their work and collections. If you would like to learn more about their project, you can read their blog at:

http://archives.wordpress.stir.ac.uk/2015/01/22/work-placements-in-conservation-2015/

Post by Emma Davey, Conservation Officer