Our final Thomson-Walker intern introduces herself in this week’s blog post….

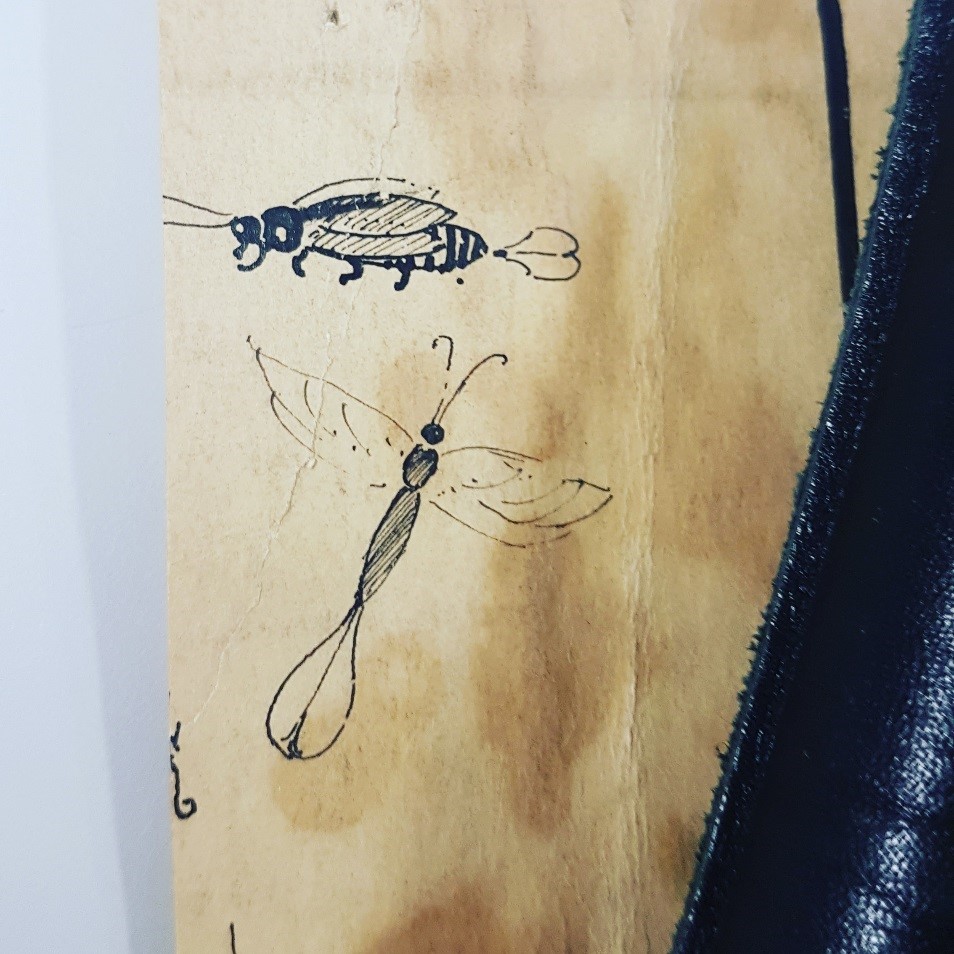

“I feel like a pastry chef!”: this was my first thought while trying to smear an even layer of a carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) poultice on a strip of lens tissue to remove a very thick residue of what distinctively smelled like coccoina (a marzipan-scented Italian glue, made from potato starch and almond paste). Being Italian, I couldn’t help but recognise the fragrance bringing back so many childhood memories. I didn’t imagine, back then, how difficult it actually is to remove this adhesive from the back of a 17th century print!

My name is Giulia, I have a Master’s degree in conservation of paper, book and photograph material, and I’m going to be the last intern working to conserve the Thomson-Walker collection of medical portraits. A little more than 600 prints of the 2,700 that constitute the collection still need to be removed from the acidic paper and board supports, and rehoused in acid-free folders and boxes, so that they can be finally catalogued, digitized and studied by researchers.

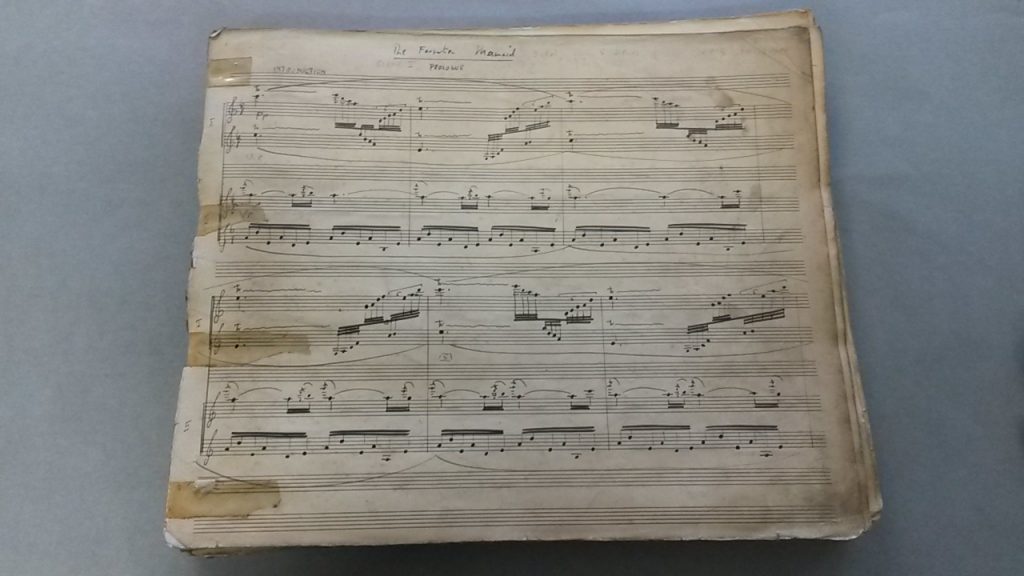

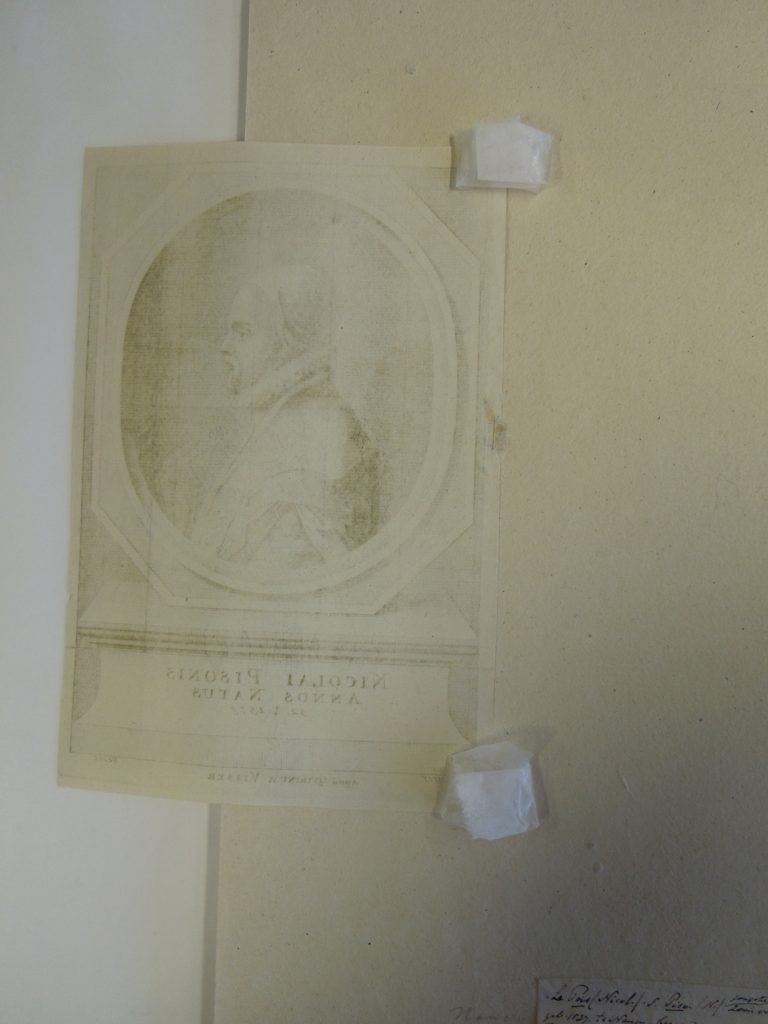

Print from the Thomson-Walker collection prior to conservation

My interest in the issues regarding the removal of adhesives has grown since I obtained my degree. In November 2016, I did a two-month Erasmus traineeship at the Archives Nationales in Paris, where I treated a series of costume inventories drawn-up with a variety of inks, that had been glued to acidic cardboard, plywood and Masonite supports (it was quite tricky to remove them: if you’d like to read about it, you can find a post about this project here, if you know a little bit of French).

So when I came across the advert for the Thomson-Walker internship, I immediately knew it would be a project I would love to take part in. What attracted me most to this project was the incomparable opportunity of working on a vast collection of prints – the second largest in the UK and one of the biggest in Europe – which spanned over 400 years and varied greatly in the printing techniques. From a professional point of view, I knew the project was going to challenge my organizational, prioritising and time-management skills, and help me acquire some practical experience in making storage solutions. During my studies, and especially after graduating, I’ve been trying to gain experience on a wide range of paper-based materials, such as scrapbooks, set models, tracing papers and, for the past six months at the National Central Library of Florence, books. I still hadn’t had the chance to work on a large collection of prints, so when I was offered the position I felt like I was adding essential experience to my checklist.

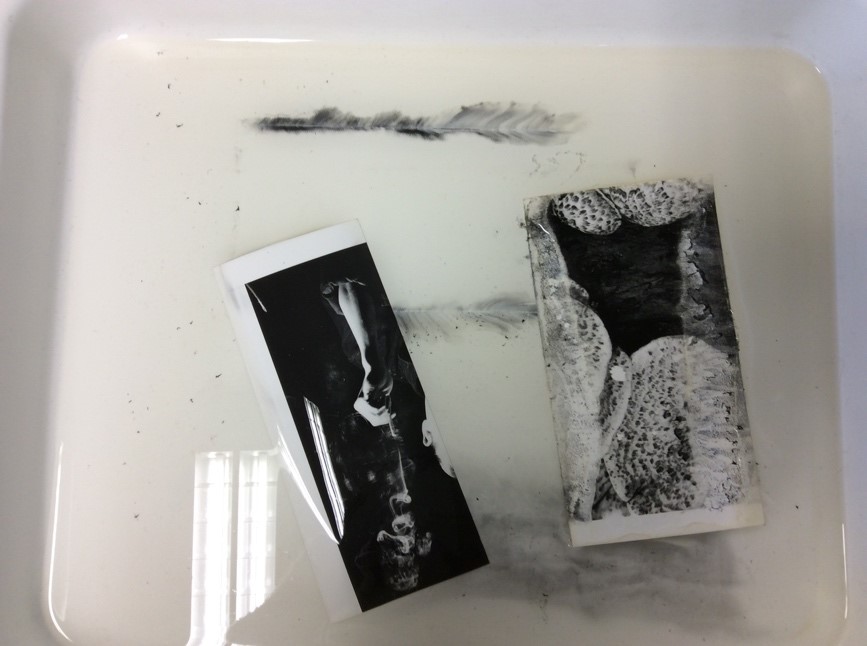

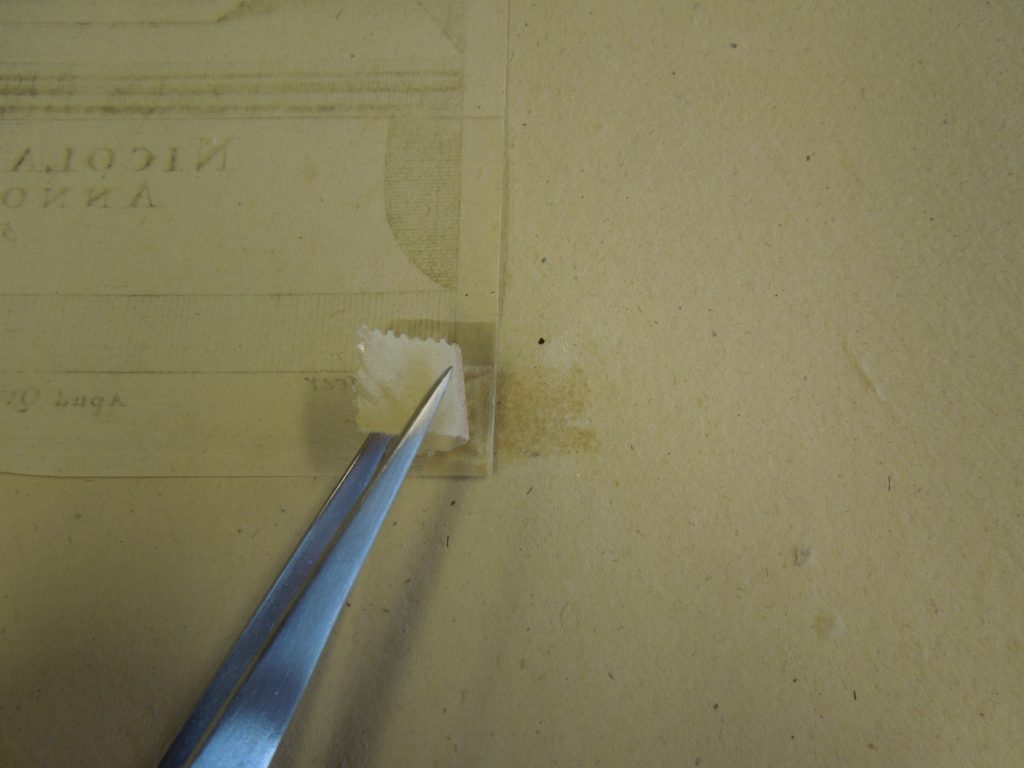

Using a poultice to soften adhesive

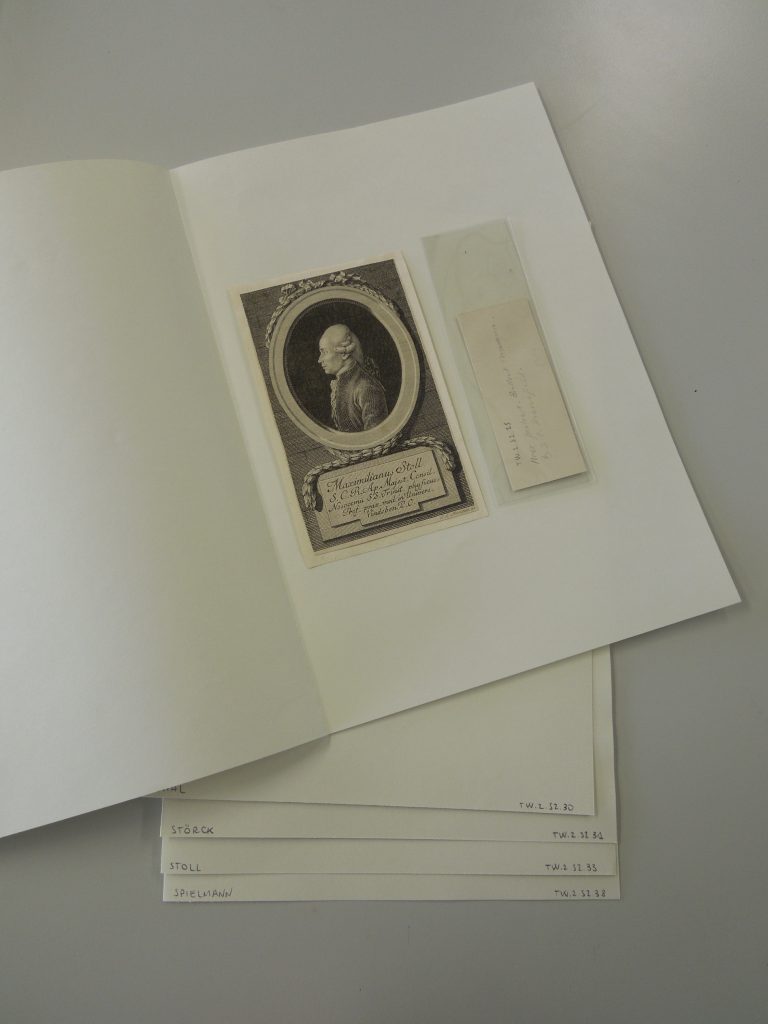

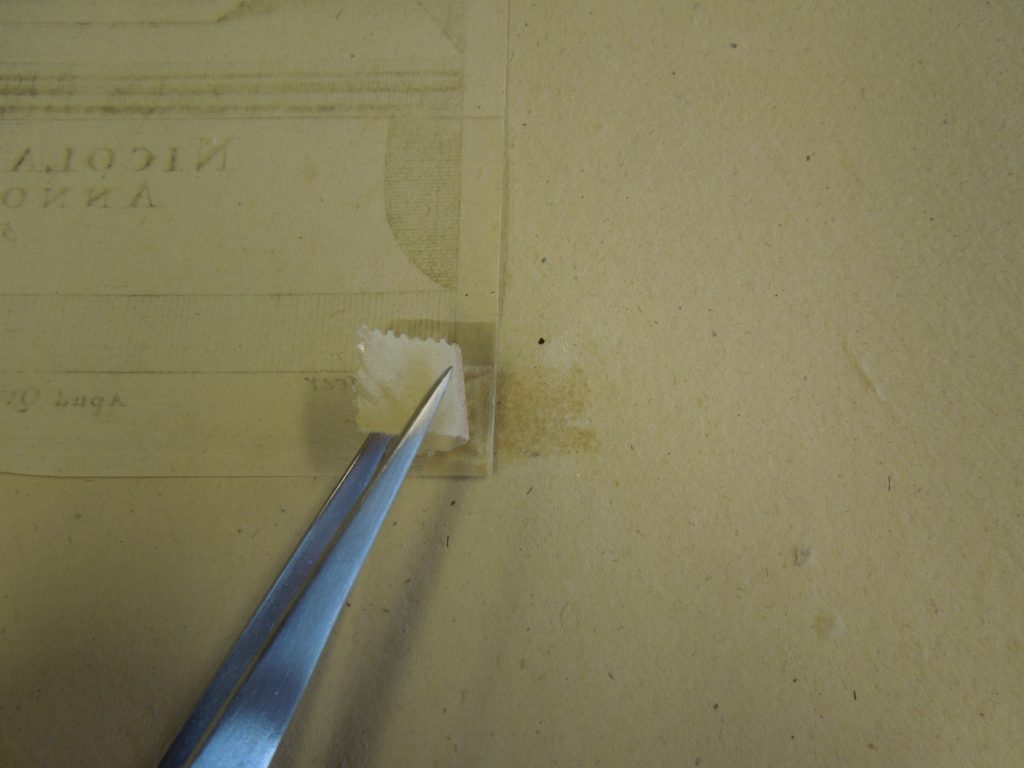

Removing paper hinge using tweezers

When reading the advert and the previous interns’ entries (here, here, here and here), I was really impressed with the rich interdisciplinary approach the CRC internship programme was offering to recent graduates. By providing meetings with other professionals working at the CRC, tours of conservation studios in Edinburgh, and assisting with volunteers and outreach activities, a preview of what it really means to work as a conservator in a public institution can be gained.

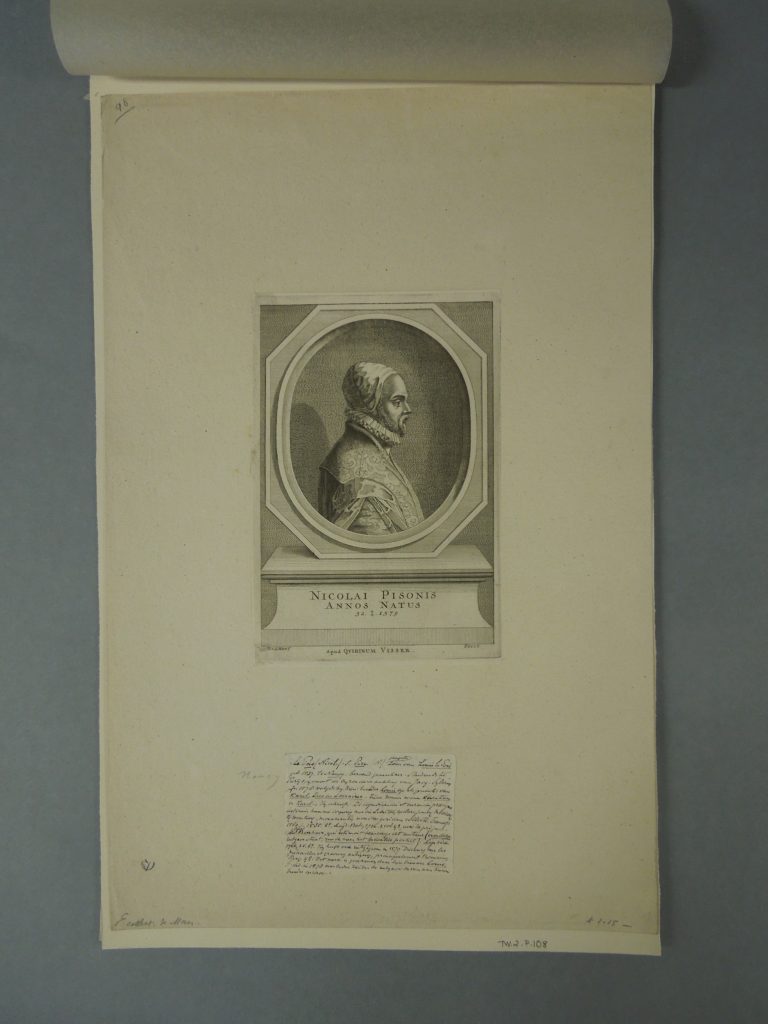

Now I have almost finished my second week at the studio, and I’m really getting into the work routine and trying my best to keep a rhythm. But then I stop for a moment, I focus on the gentleman who’s staring back at me from the small 17th century print I have just finished treating, and I can’t help but contemplating how gorgeous his portrait looks….

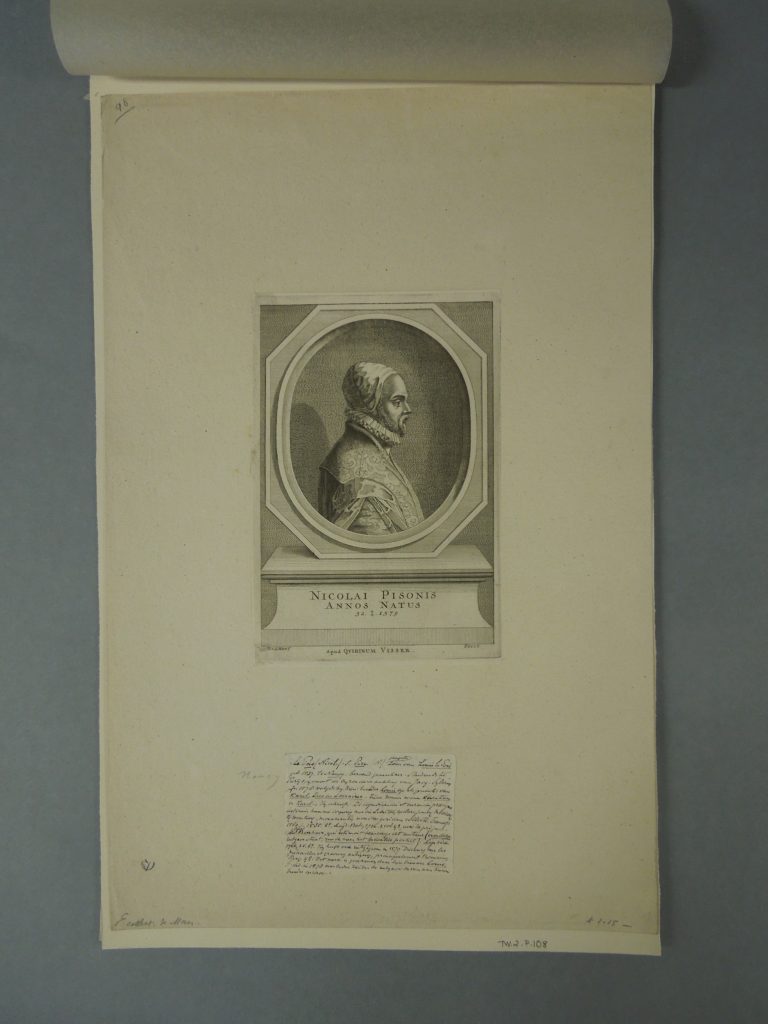

Print from Thomson-Walker Collection