February saw the start of a new project to surface clean and rehouse the CRC’s most important collection of Western medieval manuscripts, which were bequeathed to the library by David Laing in 1878. His collection contains 121 Western manuscripts, most of which are very finely illuminated or textually important.

Figure 1. Details of illuminations found in the manuscripts

Due to the age and past storage of the material, many items have accumulated a large amount of surface dirt. As well as reducing the aesthetic quality of the manuscripts, surface soiling can potentially be very damaging to paper and parchment artefacts.

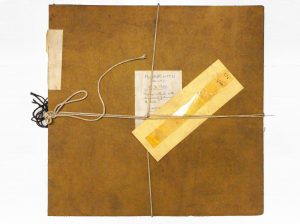

Figure 2. Accumulation of surface dirt on a manuscript

Firstly, dirt particulates can have an abrasive action on a microscopic level, causing a weakening of the fibres. Dust can also become acidic due to the absorption of atmospheric pollutants. Sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxides present in the environment, in combination with moisture and the metallic impurities found in dirt, can be converted to sulphuric acid and nitric acid respectively. This is absorbed by the pages and results in a loss of strength and flexibility. Dust can also provide a food source for insects and mould. Mould spores in the air can settle on the manuscripts and live on the organic material in the dust. At a high relative humidity, these moulds can thrive. Surface dirt can also cause staining of the item. Dirt can readily absorb moisture which causes the particulates to sink deeper into the paper or parchment fibres, making it impossible to remove by surface cleaning methods.

Figure 3. Example of ingrained surface dirt on a manuscript

To remove loose particulates, a museum vac is firstly used to quickly hoover up large amounts of dirt. It has adjustable suction levels, so it can be used on fragile items if needed. A range of attachments can be used to reach dirt in all the nooks and crannies of the manuscripts. The museum vac also has filters to prevent any mould spores removed from the book getting back out into the studio.

Figure 4. A museum vac (left) with attachments (right)

A chemical sponge is then used to remove ingrained dirt. This is a block of vulcanised natural rubber which picks up dirt and holds it in its substrate. It was originally developed to remove soot from fire damaged objects.

Figure 5. Using chemical sponge to surface clean a manuscript

Many of the manuscripts pages are extremely cockled. This has resulted in the ingress of dust further into the text block. Due to this, the manuscripts must be examined page by page to ensure all dirt is removed, which can be very time consuming, especially for the larger volumes. However, all the hard work is worth it. Knowing we are making a difference to the condition of the collection, and seeing the change in the books is very satisfying!

Figure 6. Stages of surface cleaning. Before treatment (left), cleaned with museum vac (middle), cleaned with chemical sponge (right)