RELIEF FOR BELGIUM… OFFERS OF AID FROM ALL OVER SCOTLAND

If we are to let our collections talk about the First World War, then surely the story of Charles Sarolea (1870-1953) and his efforts to aid the people of war-ruined Belgium has to be told. His wartime story emerges from the files, folders and boxes of the very large Sarolea Collection of writings and correspondence (Coll-15, Centre for Research Collections). Sarolea’s aid effort continued from the opening days of the assault on Belgium until the last months and days of the War.

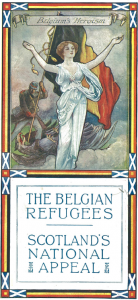

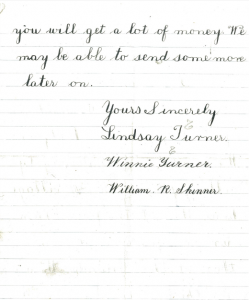

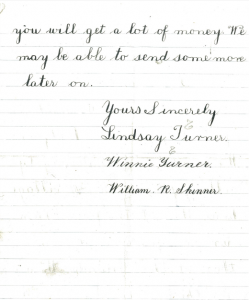

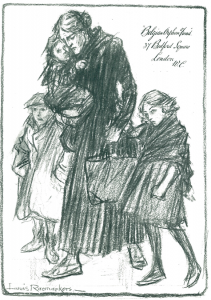

Wartime propaganda… National personification of Belgium… Mother Belgium or ‘Belgica’… ‘La Belgique’… ‘La Belge’… on a Scottish booklet published by the Belgian Relief Fund. From file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15

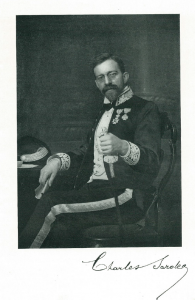

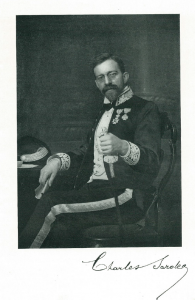

Who was Charles Sarolea? Charles Sarolea was born on 25 October 1870 in Tongeren (Tongres) in the Belgian province of Limburg. He was educated at the Royal Atheneum in nearby Hasselt before going on to the University of Liege where he was awarded first class honours in Classics and Philosophy. In 1892 he was given a Belgian Government travelling scholarship, and between 1892 and 1894 he studied in Paris, Palermo and Naples. Still in his early 20s he became private secretary and literary adviser to Hubert Joseph Walthère Frère-Orban (1812-1896) who had been Prime Minister of Belgium (Liberal Party) between 1878 and 1884. This task brought Sarolea early initiation into wide circles of international affairs, both political and cultural. Indeed later, the Belgian Royal Family would be counted among his circle.

In 1894, at the age of 24, Charles Sarolea became the first holder of the newly-founded Lectureship in French Language and Literature and Romance Philology at Edinburgh University, and in 1918 he would become the first Professor of French when that Chair was established at the University. He held a post and Chair at the University for some 37-years, 1894-1931. From 1901, Sarolea was also the Belgian Consul in Edinburgh.

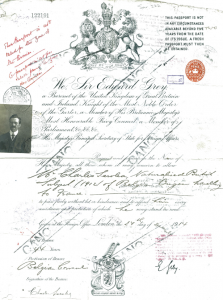

Photograph in Dr. Charles Sarolea author, lecturer, cosmopolitan in the file entitled ‘Biographical and bibliographical material relating to C. Sarolea’, in Sarolea Collection 223, Coll-15.

From 1891 until the outbreak of War in August 1914, Sarolea had written books on a wide range of international affairs and topics, including: Henrik Ibsen (1891); Essais de philosophie et de literature (1898); Les belges au Congo (1899); A Short History of the Anti-Congo Campaign (1905); The French Revolution and the Russian Revolution (1906); Newman’s Theology (1908); The Anglo-German Problem (1912); and, Count L.N. Tolstoy. His life and work (1912). From 1912 until 1917, he was also Editor of the Everyman magazine published by J. M. Dent – the magazine which features prominently in our story about Belgium.

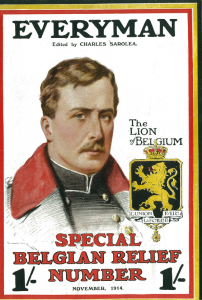

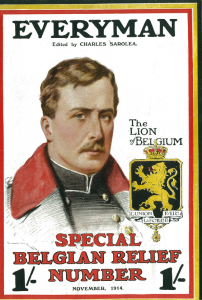

Everyman, edited by Charles Sarolea 1912-1917.

Many other resources elsewhere can tell the in-depth military and strategic story of Belgium’s stubborn resistance during the early days of the War, but a brief foray into the Belgian experience can do no harm here in a phrase or two. Basically… the Belgian army – around a tenth the size of the German army – managed to frustrate the infamous Schlieffen Plan to capture Paris, and held up the German offensive for nearly a month giving the French and British forces time to prepare for a counter-offensive on the Marne.

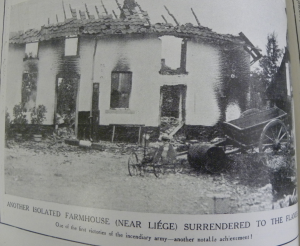

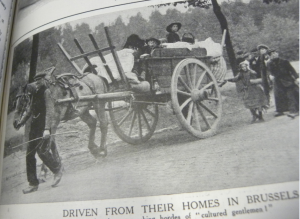

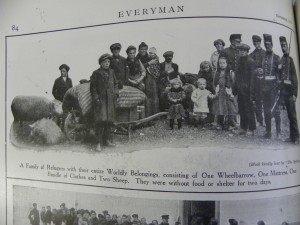

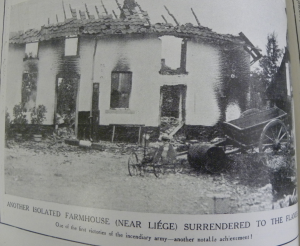

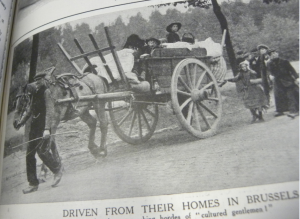

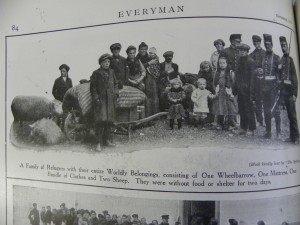

The Special Belgium issue of Everyman, November 1914, contained pictures of the war-spoiled country. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

The Special Belgium issue of Everyman, November 1914, contained pictures of the war-spoiled country. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

In this opening phase of the War, many hundreds of civilian Belgians were killed, many thousands of homes were destroyed, and nearly 20% of the population escaped from the invading German army.

Destroyed house in Malines (Mechelen) in the Province of Antwerp, Belgium. From an envelope of ‘Miss Findlay’s photographs’, in the file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund, 1914-1916′, Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15.

Goodwill towards Belgian refugees and those Belgians remaining in the country was shown right across the UK, not least in the form of the Belgium Relief Fund launched by The Times, the National Committee for Relief in Belgium, and the Belgian Orphan Fund.

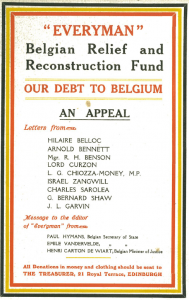

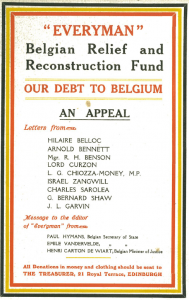

Circular advertising the ‘Everyman Belgian Relief and Reconstruction Fund’. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Also, from the very outset of War in August 1914, the Everyman magazine had established its own Belgian Relief and Reconstruction Fund and this was administered by the Charles Sarolea, the Belgian Consul, in Edinburgh, assisted by a Committee.

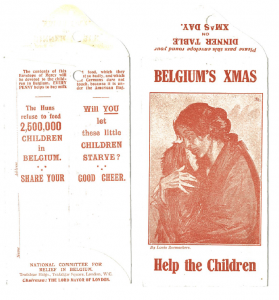

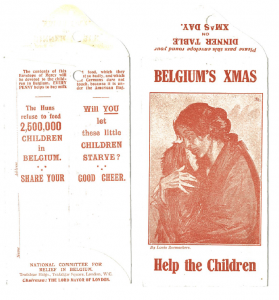

Collection envelopes issued by the National Committee for Relief in Belgium. The design showing a mother and child was by Louis Raemaekers. From a file entitled ‘Belgian Consular Correspondence, 1915-1919’, in Sarolea Collection 73, Coll-15.

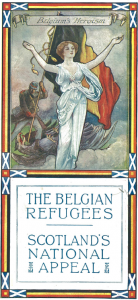

Goodwill was also registered across Scotland where a National Appeal for Belgium was opened, as this item from the Sarolea Collection shows (from file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15). The pamphlet issued by the National Appeal provided a summary of the work undertaken in Scotland where the number of Belgian refugees registered in the country in December 1915 was 13,307.

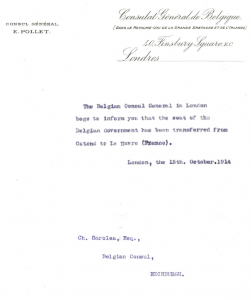

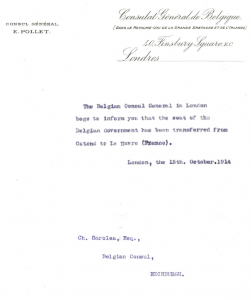

The fact that the Editor of Everyman was of Belgian origin and that he was the Belgian Consul in the capital of Scotland enabled him to be in close touch with events as they unfolded in Belgium and with the conditions of the civilian population. On 13 October 1914, as the British and French troops tried to outflank the German army – and thus establish the general shape of the Front from the Channel coast to the border with Switzerland for the next four years – Sarolea was informed by the Consul General in London (Edouard Pollet) that the legitimate Belgian government had left Ostend in Belgium for the safety of Le Havre, France.

Letter from the Belgian Embassy in London to Sarolea at the Belgian Consulate in Edinburgh indicating the removal of the Belgian government to Le Havre, France. From a file entitled ‘Belgian Consular Correspondence, 1915-1919’, in Sarolea Collection 73, Coll-15.

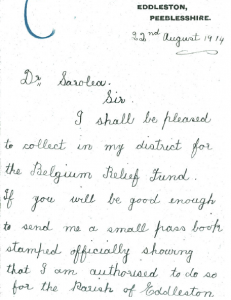

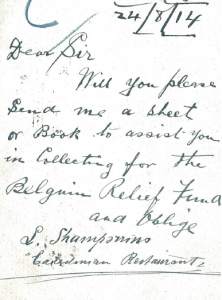

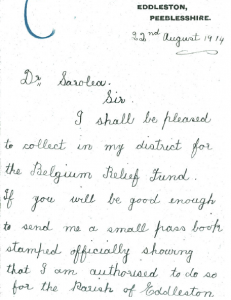

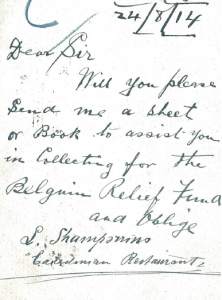

As for Belgian Relief… Sarolea and the Belgian Consulate in Edinburgh received money and requests for collecting boxes and other means of formalising the collection of funds. From all across Scotland, the Consulate also received offers of hospitality and requests for cooks, kitchen-maids, laundry-workers, nursery-maids, tutors, knitter-mechanics, sewing-maids, gardeners, grooms, house-maids and other domestic servants, and ploughmen and other agricultural workers – jobs for Belgian refugees.

A list of ‘Offers of Hospitality received at the Belgian Consulate, Edinburgh’ in the file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, notified the following generous offers…: From Eyemouth came the offer for a ‘Lad as boots in hotel, permanent’, with ‘Food, travelling clothes, all offered, and 2/6 a week and all tips, say 7/6 per week’ (2/6 was one-eighth of £1 in the old currency). From North Berwick came the offer of a post as ‘Domestic servant £18, with child £12’, and from Dunblane ‘two bed-rooms, each with double beds, for superior refugees, to live with family’, and the same household would also take ‘two Belgian servants to do work and receive wages’.

Offer of help received by Sarolea at the Belgian Consulate, Edinburgh. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15.

Offer of help received by Sarolea at the Belgian Consulate, Edinburgh. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15.

A household in Fife offered a placement for a ‘Mother and daughter (past school age) or two sisters as servants’, and the offer extended to ‘£24 for the two and help with their wardrobe’. From Peterhead came the offer to take ‘One little girl for an indefinite period’ and the girl could be taken ‘at once’. And, from the Kinnordy Estate, Kirriemuir came the offer of ‘Two houses’ for up to 44 ‘Cultivated and scientific people’ and this could include work.

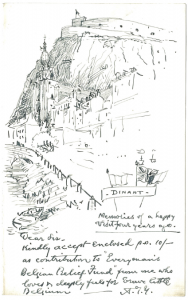

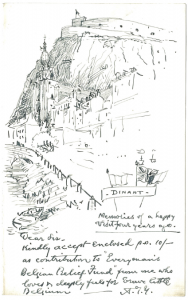

Letter with contribution to the Fund from someone who ‘deeply feels for brave little Belgium’ and who had visited Dinant a few years earlier. Dinant had been severely damaged in the first months of the war. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

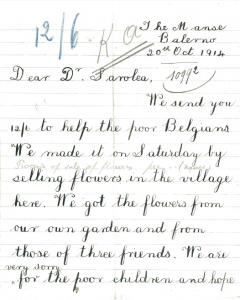

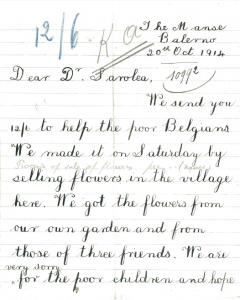

Many letters from children were received with money raised in various ways – such as selling flowers from the garden or making pictures made from postage stamps – as these letters show here:

Letter from children in Balerno, 1914. In packet/envelope ‘Letters from children for possible publication’ in the file ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund, 1914-1916′. Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Second page of the letter. In packet/envelope ‘Letters from children for possible publication’ in the file ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund, 1914-1916′. Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Picture of ‘La Belge’ by a 14-year old girl from Edinburgh, and made from postage stamps, 1914. In the file ‘Letters from children for possible publication’ in the file ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund, 1914-1916′. Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

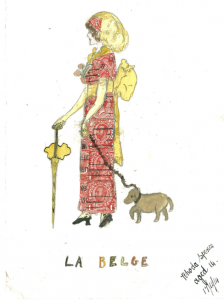

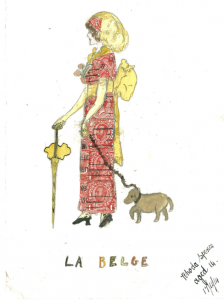

Soldiers too benefited from the charitable-giving fostered by the relief effort centred on the Belgian Consulate in Edinburgh. In 1917 an appeal was raised on behalf of Belgian soldiers ‘spending their hard-earned leave in the Edinburgh district’. In a letter from the ‘Edinburgh Consular Belgian Relief Fund’ to the Editor of the Scotsman in October 1917, it was pointed out that the pay of a Belgian soldier was only just over 2d per day (around 50p at today’s levels) and that a soldier could not afford maintenance expenses while in Edinburgh. The Fund made an appeal asking for help from ‘citizens of Edinburgh who would be willing to give those soldiers hospitality or to pay for their maintenance whilst on leave’. The Fund was sure that Edinburgh’s people would help ‘those brave Belgian lads’.

Draft letter to the ‘Scotsman’, 3 October 1917, requesting help from the people of Edinburgh for Belgian soldiers on leave in the city. From the file ‘Edinburgh Consular Relief Fund 1916-1918. Correspondence’, in the wider file ‘Everyman & Edinburgh Consular Belgian Relief Funds. Correspondence & figures, 1914-1918′. Sarolea Collection 78, Coll-15.

In November 1914, Sarolea issued a Special Belgium number of the magazine, Everyman. Illustrated with Albert I, King of the Belgians, on the front cover, the issue was seen as a ‘means of making a wider appeal to the sympathy and generosity’ of readers. Sarolea claimed that from the start of the assault on Belgium in August 1914 until the Special Belgium issue, the magazine’s ‘efforts have resulted in the raising for the relief of Belgian distress and the reconstruction of Belgian prosperity the substantial sum of thirty-one thousand pounds (£31,000)’ – a colossal sum 100 years ago, the equivalent of £3-million today. Until the Everyman effort, no weekly magazine ‘has ever raised anything like so large a sum for the public cause’.

Front cover of Everyman, November 1914. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

The Special Belgium issue was filled with articles and photographs, with many of these describing and illustrating the destruction and suffering experienced by Belgians.

Like many contemporary journals, the Everyman Special Belgium issue contained patriotic advertisements for household shopping – drinks and sweets.

In addition to papers and correspondence specifically concerning the ‘Everyman Belgian Relief and Reconstruction Fund’ within the expansive Sarolea Collection, the files also contain ephemera produced by other charitable efforts. One piece is a copy of a drawing produced by Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956) the Dutch painter and editorial cartoonist for De Telegraaf, the Amsterdam daily newspaper. His drawing was used by the Belgian Orphan Fund which encouraged the contribution of sixpence to ‘Save that Child!’

Drawing by Louis Raemaekers and used by the Belgian Orphan Fund. From a file entitled ‘Belgian Consular Correspondence, 1915-1919’, in Sarolea Collection 73, Coll-15.

Even in November 1914, those behind the Special Belgium issue of Everyman were looking ahead to the end of the War which many believed would be of short duration. A piece by the Belgian-British Reconstruction League talked of the ‘tremendous task’ ahead. ‘A whole country will have to be reclaimed from devastation. A whole people will have to be repatriated and resettled’. As the War ground on though, Sarolea travelled extensively during 1914 and 1916 – across France and to Switzerland and Italy – as his passport shows.

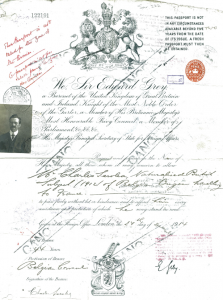

Passport issued in December 1914 to Charles Sarolea, naturalised British subject of Belgian origin, travelling to France… but not valid for travel in Army zones. In the file entitled ‘C.S. personal documents, Passport etc’. Sarolea Collection 222, Coll-15.

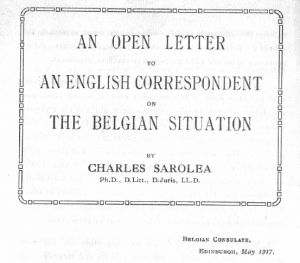

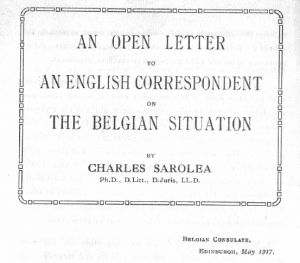

The ‘Everyman Belgian Relief and Reconstruction Fund’ was wound up towards the end of 1917, and real reconstruction across Belgium would be well underway by the early 1920s. By the end of the war, some 200,000 Belgians had sought refuge across the UK – 17,000 in the Glasgow area alone – and around £6-million to £7-million had been contributed to all of the Belgian charities (circa £400-million today), and these figures were used by Sarolea in his defensive ‘open letter’ to an English correspondent who had criticised the effort.

Sarolea defended charitable giving to Belgians in this ‘open letter’ written in May 1917. From the file ‘Belgian Consular Correspondence, 1915-1919’. Sarolea Collection 73, Coll-15.

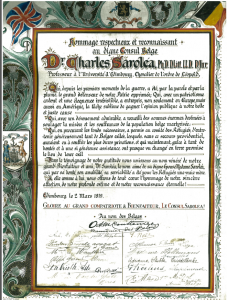

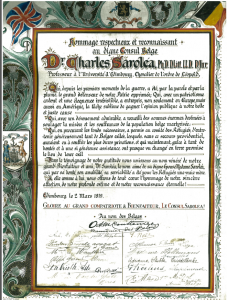

Immediately after the War, in March 1919, in Edinburgh, Charles Sarolea was presented with an illuminated scroll by grateful Belgians honouring his wartime work for aid to Belgium. Heading the signatures on the scroll was that of the Rev. O. M. Couttenier a Belgian priest in Edinburgh.

Scroll presented to Charles Sarolea by grateful Belgians. Sarolea Collection 222, Coll-15.

Professor Charles Sarolea resigned his Chair in 1931 but continued to reside in Edinburgh and remained as Belgian Consul in the city until his death in 1953. In 1954, his papers and correspondence were purchased for Edinburgh University Library.

Detail from the front cover of Everyman, November 1914. In a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections