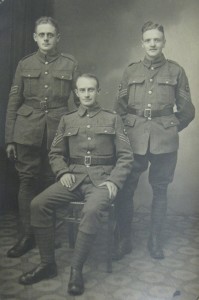

MacDiarmid (left) with fellow officers (Gen. 2236/3/11)

The Papers of Andrew Graham Grieve (Gen. 2236) include a poem from a forgotten front of the First World War written by his older brother Christopher Murray Grieve, later to achieve fame as Hugh MacDiarmid.

Grieve/MacDiarmid had initially opposed the war as a capitalist adventure running counter to the interests of the working classes. The death of school-friend John Bogue Nisbet at the Battle of Loos caused a change of heart, however, and he enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps in July 1915. Following training in England, he was posted as ‘Sergeant-Caterer of the Officer’s Mess’ to the 42nd General Hospital in Thessaloniki, Greece (then more widely known as Salonika), where an Allied expeditionary force had established a base for operations against pro-German Bulgaria. Arriving in summer 1916, MacDiarmid joined a Scottish contingent so great that wags nicknamed the city ‘Thistleonica’.

Writing to his mentor and former teacher George Ogilvie, MacDiarmid described the posting as a ‘cushie job’, giving a vivid account of his duties in a letter dated 20 August 1916:

The Sergeant-Caterer of the Officers’ Mess (that’s my new post in our little military world here) has to go ‘on deck’ at dinner – dinner commencing at 7.30 p.m. and running to some five courses – freshly-shaven, boots and buttons mirror-bright, properly dressed with belt and all. He does nothing, of course, save supervision. A spot of tarnish on a knife or fork – lack-lustre of a wine glass – uneven flaming of one of the hanging lamps – slackness on the part of the waiters – slow, slovenly, or uneven dishing-up on the part of the cooks – what an eye one develops for detail on such a job! […] and later when the Mess has come to the walnuts and almonds and the wine-steward is busy supplying Vin Blanc, Vin Russe, or Vin Muscat de Samos […] the Sergeant-Caterer and his staff dine too. (What an awful war, to be sure!)

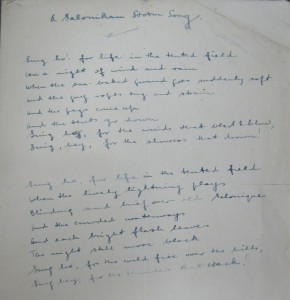

The same blithe spirit is reflected in ‘A Salonikan Storm Song’, a poem signed ‘C.M.G., Salonika, 1st September 1916’ and sent to brother Andrew. A humorous depiction of the effects of a summer storm on a field hospital, it concludes:

Sing ho, for life in a tented field

On a night of storm and stress

Where chaos prevails and everything is

In the very deuce of a mess

And soaked and muddy and blown about

We still can laugh and sing

While the rain comes down in bucketfuls

And the wild fire has its fling!’

MS of ‘A Salonikan Storm Song’ (Gen. 2236/7)

While hardly the kind of verse we now associate with the First World War (let alone with MacDiarmid!), the bravado of ‘Salonikan Storm Song’ is, in fact, typical of the military poetry published during the war itself. It seems likely that this poem formed part of a collection that MacDiarmid submitted to Erskine MacDonald’s ‘Solder Poets’ series under the projected title A Voice from Macedonia. Although provisionally accepted by MacDonald and praised by John Buchan, an early supporter of MacDiarmid who read it in manuscript, the collection never saw the light of day. Following protracted printing delays, MacDiarmid withdrew his MS, feeling that it was no longer timely.

Later comments by MacDiarmid reveal that life in Salonika was not quite as ‘cushie’ as the poem and the letters to Ogilvie suggest. Disease – malaria, blackwater fever, dysentery — was rampant, killing many more soldiers than the enemy did. In an interview given to Stella Duffy in 1975 (quoted in Alan Bold’s biography of the poet), MacDiarmid spoke of the extraordinary mortality rate and of the many friends he saw die in the General Hospital. MacDiarmid himself suffered three bouts of malaria and was eventually invalided home in May 1918.

A young MacDiarmid with Andrew Grieve (right) (Gen. 2236/3). The brothers endured a fractious relationship.

In the autobiographical Annals of the Five Senses (1923), he described the prevailing atmosphere in Salonika as one of ‘highly-coloured nightmarish unreality’, caused by the prevalence of disease, irregular mail, strict censorship, late and unreliable news, and a suspicion (endorsed by many historians) that the whole expedition was a ‘superfluous sideshow’. As MacDiarmid remarks, the Germans were known to joke that Salonika – home to 400,000 allied troups — was ‘the cheapest internment camp they had’. From a purely literary perspective, he wondered whether the ‘comparative stagnation and monotony’ of life in the city, coupled with the ‘gruesome dull routine of disease and misadventurous death, unaccompanied by the flame of guns and the glitter of steel’, dulled the imagination and explained why the Eastern Front produced much less memorable verse than the Western.

Nonetheless, the two years in Salonika proved a crucial formative experience for MacDiarmid. Ample time for reading, a multilingual atmosphere (the city housing French, Greek, Russian, Serbian, and Commonwealth troups), news of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, all helped forge the Marxist nationalism which would inspire his post-war poetry.

Paul Barnaby, Archives Team

Sources

- Alan Bold, MacDiarmid = Christopher Murray Grieve: A Critical Biography (London: John Murray, 1988)

- C. M. Grieve, Annals of the Five Senses, 2nd edn (Edinburgh: Porpoise Press, 1930)

- J. T. D. Hall, ‘Hugh MacDiarmid Author and Publisher’, Studies in Scottish Literature, 21.1 (1986), 53-88.

- The Hugh MacDiarmid-George Ogilvie Letters, ed. Catherine Kerrigan (Aberdeen University Press, 1988)