‘…AN ACCOUNT OF THE GREAT CONTEST NOW IN PROGRESS…’

On the approach of the 100th Anniversary of the Russian Revolutions, this second look at The Times History and Encyclopædia of the War, focuses on how the publication reported on Russia and Russian campaigns during the First World War. The blog-post nods towards the 100th Anniversary of the February Revolution 1917 – which led to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and which was followed by a second revolution a few months later in October 1917… and which also led to the independence of Finland.

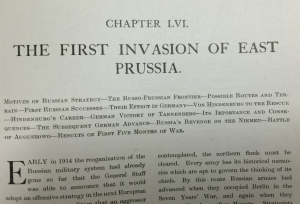

Chapter heading for a part of the history concerned with Russian action in East Prussia during the First World War, in Part 32, Volume 3, p.223.

Detailed accounts of the Eastern Front of the First World War can be read elsewhere, but this thumb-through of various issues and volumes of The Times History presents a brief description of reports and illustrations from the Front, and offers a countdown to the Russian Revolutions of February and October 1917.

In contrast to the Western Front stretching from the North Sea to Switzerland, the vast Eastern Front stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. While action in the west focussed on Luxembourg, Belgium and France, and involved the armies of the British and French Empires against Imperial Germany, action in the east stretched deep into Central Europe and involved the armies of Imperial Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire (the Central Powers) against Imperial Russia and Romania, providing ‘shatter’ to the region that would pale into insignificance in a second round of destruction in the early-1940s. There was of course a Southern Front in Europe too, pitching Italian forces against the Central Powers.

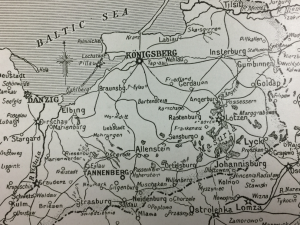

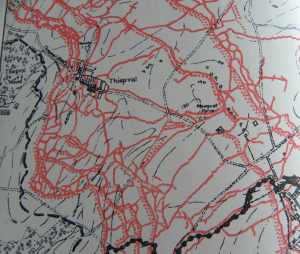

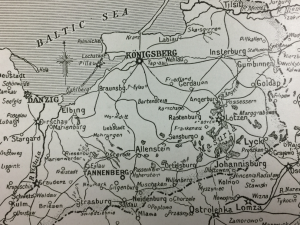

Map accompanying the account of Russian action in East Prussia during the First World War, with Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes shown, in Part 32, Volume 3, p.224.

As the First World War opened, the Central Powers were met with a war on two fronts. On the Eastern Front, the Russian army attempted an invasion of East Prussia, striking the historical and ancestral heartlands of the German Empire. The Russians achieved some success initially but then they were beaten back at the Battle of Tannenberg in late-August 1914, with Imperial Germany securing the routes to its ports of Danzig (Gdansk, now in Poland) and of Königsberg (Kaliningrad, now a Russian exclave on the Baltic).

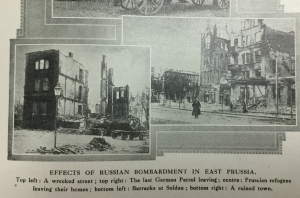

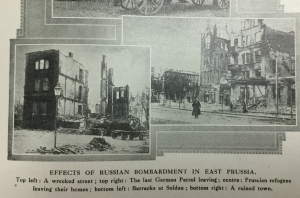

‘The Times History’ included pictures of ruined villages and towns as a result of fighting in East Prussia during the First World War, in Part 32, Volume 3, p.227.

Tannenberg saw the near complete destruction of the Russian 2nd Army, and a series of follow-up battles around the Masurian Lakes destroyed most of the Russian 1st Army as well, and knocked the country off balance until early-1915.

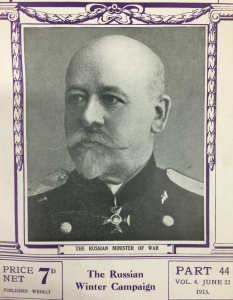

Vladimir Aleksandrovich Sukhomlinov (1848-1926), Cavalry General of the Imperial Russian Army and Minister of War until 1915, on front cover of ‘The Times History’, Part 44, Volume 4.

Early Russian defeats fell on the shoulders of the Minister of War, Vladimir Alexander Sukhomlinov, who was forced out of office in 1915 and replaced by Infantry General Alexei Andreyevich Polivanov.

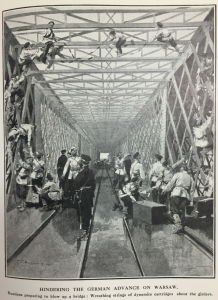

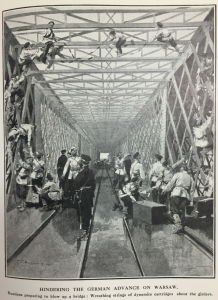

Russians preparing to blow up a bridge in order to hinder the German advance on Warsaw, in Part 61, Volume 5, p.329.

Although the Russians achieved successes in Galicia (now part of western Ukraine), and in the Carpathian Mountains, by mid-1915 they had been pushed out of ‘Russian Poland’ so removing the threat – at this very early point in the war as it would unfold – of any Russian invasion of Imperial Germany or Austria-Hungary.

A Russian motor-cycle battalion. In 1914 the Russian Army was the largest army in the world but poor roads and railways made the effective deployment of soldiers difficult, illustration in Part 97, Volume 8, p.204.

This ‘Great Retreat’ by Imperial Russia from Polish territory – carved up between themselves, Austria-Hungary, and Prussia back in the 18th century – was a severe blow to Russian morale.

Blessing of the Russian forces at Kazan Cathedral, St. Petersburg, in Part 97, Volume 8, p.220.

Polivanov, the new Minister of War, started transforming the Russian army’s training system and tried with limited success to improve its supply and communications systems. Army losses in manpower were easily filled from the vastness of the Empire.

Russian war loan poster, in Part 97, Volume 8, p.226.

The huge size of the Russian population and the loyalty of large swathes of the people to the Tsar and to the Russian Orthodox Church – and thus to the protection of ‘Holy Russia’ with the Tsar at its head – meant that a formal draft of able-bodied men was unnecessary. Instead, the government of Nicholas II released pamphlets encouraging people to buy government bonds to fund the war with rates for the loans standardised at 51⁄2% return per month.

Tsar Nicholas II visiting a munitions factory, in Part 97, Volume 8, p.203.

In August 1915 Polivanov became aware of the plan by the Tsar to replace his Romanov relation Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and to himself lead the Russian armies at the front, and made strenuous efforts to persuade him not to. This was in vain, and in 1915 Nicholas II took personal command of the Russian armed forces and spent long periods at Mogilev (now in eastern Belarus) as Commander-in-Chief hundreds of miles from events unfolding in the capital… events on the home front.

Illustration of ‘Grand Duke Nicholas in the Caucasus’ accompanying a chapter on the Russian Campaign in Armenia, 1915-1916, in Part 124, Volume 10, 2 January 1917.

Polivanov’s efforts to prevent the Tsar from taking control helped alienate him from the Tsarina, who then conspired to have him sacked. This was achieved when the Tsar dismissed the Minister of War in March 1916.

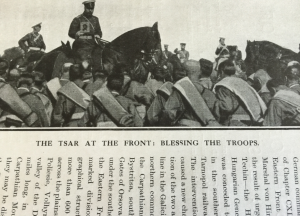

Illustration of ‘The Tsar at the Front Blessing the Troops’, in part 122, Volume 10, p.162.

On the home front, opposition and revolutionary sentiment was increasing. There were disruptions to the fuel supply, inflation was escalating, the price of meat, sugar and firewood was increasing, and there were continuous shortages of flour and coal. Added to these problems were the difficulties caused by refugees fleeing east, deeper into Russia, both from the army’s own scorched-earth policy entailing the destruction of entire villages and the indiscriminate forced removal of civilians, and from territories that had become controlled by the enemy.

Illustration, ‘Russian refugees returning home’, from the front cover of Part 122, Volume 10, 19 December 1916.

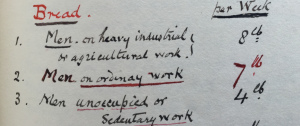

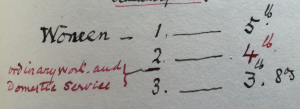

With the collapse of food supplies, and with growing food queues, the breakdown of authority on the home front began to accelerate. Strikes and street demonstrations broke out in the first few days of March 1917 (towards the end of February in the old-style Julian calendar still retained in Russia). On 8 March strikers were joined in their protests by those celebrating International Women’s Day and those protesting against food rationing. On 9 March some 200,000 people were on the streets of Petrograd (St. Petersburg) demanding the end of the war and the abdication of the Tsar.

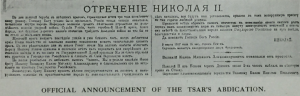

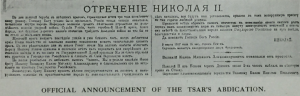

The official announcement of the Tsar’s abdication, Part 169, Volume 13, p.434.

On 10 March, from his front-line base at Mogilev the Tsar requested the Petrograd garrison commander to disperse the crowds with gunfire but this was met with reluctance among the soldiers. Rioting broke out and on 11 March the Tsar ordered suppression of the rioting by force. This was met with mutiny and by nightfall of 12 March, the Russian Imperial capital was in the hands of revolutionaries. Army Chiefs and government Ministers advised the Tsar to abdicate the throne, and this he did on 15 March 1917.

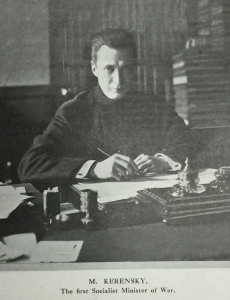

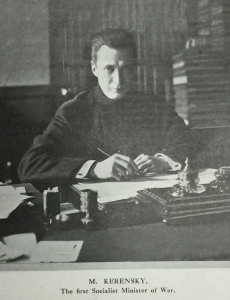

Alexander Kerensky who replaced the first head of the Provisional Government, Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov, in July 1917, in part 169, Volume 13, p.435.

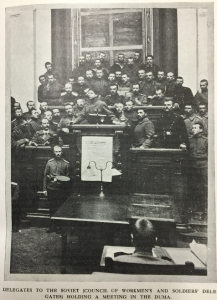

On 16 March, a centre-left Provisional Government was announced and it was headed by the liberal Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (1861-1925), although socialists had formed a rival body a few days earlier – the Petrograd Soviet (the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies). In a power-sharing agreement, the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet held ‘Dual Authority’.

Illustration showing ‘Russian troops in France taking the oath of allegiance to the new Russian government’. It shows General Lohvitzky and officers in front of the troops, in Part 169, Volume 13, p.451.

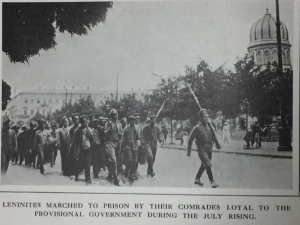

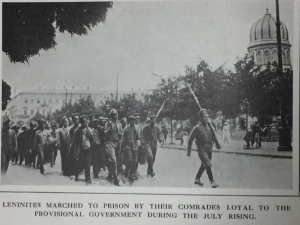

Meanwhile the Russian communist revolutionary Vladimir Ulyanov Ilyich Lenin arrived in Petrograd in April 1917 and immediately began to undermine the Provisional Government, calling for ‘all power to the soviets’ (not simply dual power) and an end to the ‘predatory imperialist war’. Lenin did not have widespread support, even among Bolsheviks, and during the spontaneous armed demonstrations by soldiers and industrial workers – protests during the ‘July Days’ – he was unable to direct them into a organised coup against the government. Lenin was forced to flee to Finland and other Bolsheviks were arrested.

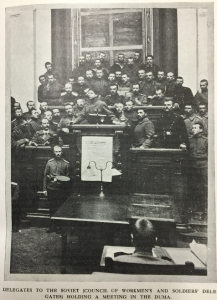

Illustration showing ‘Delegates to the Soviet (Council of Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Deputies) holding a meeting in the Duma’, in Part 169, Volume 13, p.457.

One outcome of the ‘July Days’ however was the replacement of Lvov as head of government. He was replaced by Alexander Kerensky of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. Kerensky declared freedom of speech, ended capital punishment, released thousands of political prisoners and did his best to maintain Russian involvement in the War.

Illustration showing aftermath of the ‘July Days’ 1917, in Part 180, Volume 14, p.361.

The ‘July Days’ unrest had been precipitated by continued Russian involvement in the War. Nevertheless, in an ill-timed move, Kerensky ordered a new military offensive in July 1917 – the ‘Kerensky Offensive’, or ‘July Offensive’. It was led by General Brusilov, aided by Romania forces, and was launched against Austro-Hungarian and Imperial German armies in Galicia. The offensive was initially successful but Russian losses soon mounted and their advance collapsed. They were met with a counter-attack and in the end had to retreat around 240 kilometres. Mutiny and demoralisation within the Russian military had also played a part in the collapse.

Illustration showing ‘The Russian offensive of July 1917’, part 170, Volume 14, p.23.

The events of July, coupled with continued military defeat and striking and unrest in the cities, encouraged a resurgence of right-wing forces. In August 1917, with Kerensky’s agreement initially, General Lavr Kornilov, Commander-in-Chief of the Provisional Government forces, directed an army to Petrograd with the intention of restoring order to the country. However fearing an army putsch Kerensky reversed his agreement for this, but Kornilov pressed forward with his plans anyway. Kerensky was forced to turn to the Petrograd Soviet for help, the outcome of which was the rearming of the Bolshevik Military Organization and the release of Bolshevik political prisoners, including Leon Trotsky. Bolsheviks, Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries confronted Kornilov and convinced the army to stand down.

Illustration showing ‘The Smolny Institute, Petrograd, Headquarters of the Bolsheviks and guarded by Red Guards and Militia-Police’. The Smolny was Lenin’s residence for several months until national government was moved to Moscow and the Kremlin in March 1918. Image in Part 180, Volume 14, p.387.

The ‘Kornilov Affair’, was followed by renewed military action and the fleeing of Russian forces from Riga (now capital of Latvia) when the city was attacked and captured by advancing German troops in September 1917. Throughout September and October there were mass strike actions by the Moscow and Petrograd workers, miners in Donbas, metalworkers in the Urals, oil workers in Baku, textile workers in the Central Industrial Region, and railway workers throughout the Russian network. More than a million workers took part in strikes, and workers took control over production and distribution in many factories and plants in a social revolution. In September, Lenin had returned to Petrograd too.

On 7 November 1917 (or 25 October in the old-style Julian calendar) the Bolsheviks led their forces in the uprising in Petrograd against the Kerensky Government – the October Revolution. On 6 December 1917, Finland – an Imperial Russian Grand Duchy since 1809 and before that part of a greater Sweden from the 12th and 13th centuries – declared itself independent. After the revolutions, both countries would undergo deeply rending civil wars.

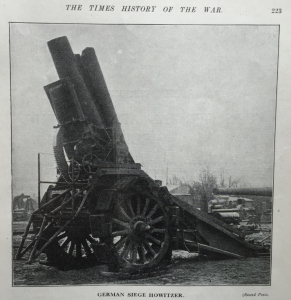

A further look at The Times History and Encyclopædia of the War will be taken in the next few months… possibly looking at reporting by the publication on heavy industry and armaments.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections (CRC)

![]() The British War Medal was awarded to those who served in the campaigns of the Great War or World War between 5 August 1914 (the day following the British declaration of war against the German Empire) and the armistice of 11 November 1918… both dates inclusive. As war approached again in the mid-1930s, this Great War or World War became known as World War One.

The British War Medal was awarded to those who served in the campaigns of the Great War or World War between 5 August 1914 (the day following the British declaration of war against the German Empire) and the armistice of 11 November 1918… both dates inclusive. As war approached again in the mid-1930s, this Great War or World War became known as World War One.![]() The British War Medal – a medal of the First World War – was established on 26 July 1919. In its Silver version, 6,390,000 were awarded. Some 110,000 Bronze versions of the medal were awarded to labour battalions. The British War Medal was designed by the Aberdeen-born sculptor William McMillan (1887-1977).

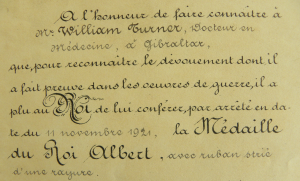

The British War Medal – a medal of the First World War – was established on 26 July 1919. In its Silver version, 6,390,000 were awarded. Some 110,000 Bronze versions of the medal were awarded to labour battalions. The British War Medal was designed by the Aberdeen-born sculptor William McMillan (1887-1977).![]() The British War Medal shown here was the one awarded to Edinburgh University alumnus William Hunter who served in Serbia during the Great War (see the May 2015 post of these Untold Stories, ‘William Hunter & the Order of St. Sava’). Hunter was President of the Advisory Committee, Prevention of Disease, in the Eastern Mediterranean and Mesopotamia (Gallipoli, Egypt, Salonika, Malta and Palestine), and he also served with the Eastern Command, 1917-1919.

The British War Medal shown here was the one awarded to Edinburgh University alumnus William Hunter who served in Serbia during the Great War (see the May 2015 post of these Untold Stories, ‘William Hunter & the Order of St. Sava’). Hunter was President of the Advisory Committee, Prevention of Disease, in the Eastern Mediterranean and Mesopotamia (Gallipoli, Egypt, Salonika, Malta and Palestine), and he also served with the Eastern Command, 1917-1919.![]() Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, CRC

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, CRC