The following was written by Gillian McDonald, a MSc Scottish Studies intern, who spent some time in early 2013 looking at selected items in the archives of the two institutions and analysing how World War 1 changed things on the ground.

The First World War had an enormous impact on Scottish society as a whole, but it also had an important effect on specific institutions. The Minutes of the University Court provide an insight into how the war affected the University of Edinburgh, and similar official minutes and other records provide information about Edinburgh College of Art’s reaction to the Great War. During my eleven-week internship at the Centre for Research Collections at the University of Edinburgh, I was able to study this material in detail and discover the many ways in which the war altered the normal running of both institutions.

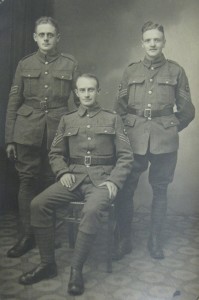

Perhaps the most obvious impact the war had was on the decreasing number of staff and students able to attend the University. Within the first few months of war, the University Court Minutes had already reported on several cases of members of staff applying for leave of absence in order to take up military service. As the war continued, and conscription was eventually introduced, these numbers only increased further. It was not just military service, however, that prevented members of staff from undertaking their normal duties; some staff members took leave of absence in order to do other war-related jobs. For example, Mycology Lecturer Dr Malcolm Wilson became a Pathologist in the County of London War Hospital, and Mr H.W. Meikle, Lecturer on Scottish History, took on a post in the Intelligence Section of the Ministry of Munitions for the duration of the war.[1] The Minute Books from Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) show a similar story, with many members of staff applying for leave of absence whether to join the military services or to undertake other kinds of war work. This affected janitors, attendants and secretarial staff as well as teaching staff; in July 1916 Attendant Thomas Monteith applied for leave of absence to join His Majesty’s Navy, whereas his colleague Robert Sloane undertook work in a munitions factory during wartime.[2] In most cases, both at the University and at ECA, positions were kept open for the staff members’ return and the institutions paid the difference when military pay was less than their usual salaries. This proved to be a huge drain both on funds and resources, as not only did the University and ECA have to pay partial salaries of absent staff, but those who remained in employment had to undertake extra work to keep classes running. In some instances, it was simply not possible to continue with so many absent members of staff; in June 1916 it was decided that Elementary Greek, Elementary German, Political Economy, Arabic, History of Medicine and Physical Methods in the Treatment of Disease should be suspended during the 1916-17 term.[3]

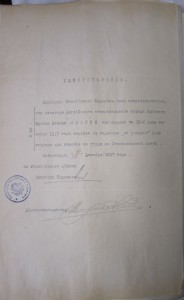

The absence of a great number of students proved to be an arguably even bigger problem. In 1914, the majority of income for Scottish Universities was derived directly from student fees, but with the bulk of students being military-aged men this income ground to a halt during the war. As early as January 1915, the Courts of the four Scottish Universities had arranged to establish a Conference and prepare a joint memorial to be sent to the Treasury in order to obtain additional funding.[4] This funding was granted due to the ‘special circumstances’ of the war, and continued throughout the conflict. The huge scale of the First World War created the need, for the first time, for widespread state intervention in the running of Scottish Universities. These grants did not end as soon as peace was declared; in May 1919 the Treasury paid the University of Edinburgh an annual grant of £53,000, as well as a non-recurrent grant of £20,000 to help the University restore itself to a pre-war standard.[5] ECA also required financial help to cover the deficit created by a lack of fee-paying students; the Scotch Education Department granted a payment of £8,679 for the session 1914-15, and other similar payments were made throughout the war.[6] Another source of income was from the Carnegie Trust; the newly created Conference of the four main Scottish Universities met regularly throughout the First World War to discuss financial issues, and were able to secure special grants from the Carnegie Trust.[7]

With so many young men absent from the University, one group of students were actually able to improve their position during the war. Women were a very small minority of students in 1914, but by the end of the war their presence had become more widespread in Edinburgh University. Female students had not previously been admitted to the University of Edinburgh Medical School, instead studying at Surgeon’s Hall. With an increasing number of female medical students due to the special circumstances of wartime, Surgeon’s Hall was no longer able to provide satisfactory accommodation and resources and so suggested in June 1916 that women should be admitted to the University to study Medicine. Following many letters and petitions, the following month saw the University agreeing to ‘make provision within the University for the instruction of women in the Faculty of Medicine’.[8] Throughout the war, the Women Students’ Union campaigned for better facilities for female students, but it was not until February 1919 that the University agreed to let out a property in George Square solely for their use.[9] The lack of available male staff also benefitted women as they were often appointed as substitute lecturers, assistants, demonstrators and examiners. The same could be seen at ECA; Dorothy Johnstone, for example, was appointed in place of Walter B. Hislop, an Assistant Teacher in the Drawing and Painting Section who served with the 5th Royal Scots during the war.[10] Perhaps due to the nature of courses on offer, female students already enjoyed a relatively prominent position at ECA so the war did not cause as major a change for them as it did for University students.

As well as the cancellation of some classes and extra provision for women in others, new classes were also introduced to help cater to the needs of a society at war. In June 1915 there were discussions to introduce a course in Military Science which would be open as a qualifying class to ‘all men who have served or are serving with His Majesty’s Forces’.[11] Following the introduction of conscription, however, the Lectureship on Military Subjects as suspended as there were no current or prospective students. Instead, more emphasis was put on ‘practical’ courses which would help keep the country running throughout the war, and aid in rebuilding it after peace was declared. In December 1917 developments began to improve the Forestry Department to cater for the extended teaching which was probable after the war. This began with the conversion of the Lectureship into a Chair, and then in May 1918 a special Diploma and Certificate in Forestry was established which would be open only to those who had served with His Majesty’s Forces during the war.[12] In May 1919 the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce gave the University £15,000 for the purpose of endowing a Lectureship in the subject of Industry and Commerce.[13] Some special courses were set up for demobilised men; schemes were introduced to provide education for invalided Colonial soldiers, and courses in Town Planning and Civic Design were to be provided to train discharged and disabled officers.[14] The Edinburgh Lipreading Association set up special classes at ECA for teaching lipreading to soldiers and sailors deafened in the war, and the men would also be able to attend Art classes whilst they were studying at the College. Convalescent Officers, who had some previous training in art, from Craiglockhart Hospital were also able to study at ECA without payment of fees.[15] It was common for both the University and ECA to admit those who had served in the war, as well as allied refugees, to classes free of charge or at a reduced rate. Some courses which had traditionally been a part of University teaching, however, declined in importance. Despite a Chair of German being established during the war there were strong objections to it due to popular anti-German sentiments, and steps were taken to ensure that no one was appointed to fill the position until after the war ended.[16]

As has been previously mentioned, the First World War saw increasing state intervention in Scottish Universities on a financial level, but during the war itself the state also had a physical presence within both the University of Edinburgh and ECA. The Local War Department took over the Edinburgh University Field Pavilion ‘for the purpose of billeting twenty-five men of the Army Service Corps’ in December 1916, and in February 1918 the Music Hall was commandeered by the Ministry of National Service.[17] The Board of Agriculture also made inquiries in January 1917 about taking over land belonging to the University in order to convert as much vacant land in the city as possible to allotments which were vital in the ‘present emergency’.[18] University premises were also used by other organisations and individuals for war-related activities; the Women Students Help Association used a room in the University as their Office and Committee Room to organise the provision of clothing and ‘articles of comfort’ for soldiers and sailors.[19] The government also had a noticeable presence at ECA during the war. The Food Control Department took over use of several classrooms in August 1917, and several other parts of the College were used by the Local Fuel and Lighting Department.[20] The Ministry for National Service also intended to take over a large portion of the building, but ECA was already overstretched and so it was decided to locate the offices for the Scottish Region Headquarters of the Ministry for National Service at the Royal (Dick) Veterinary School instead.[21]

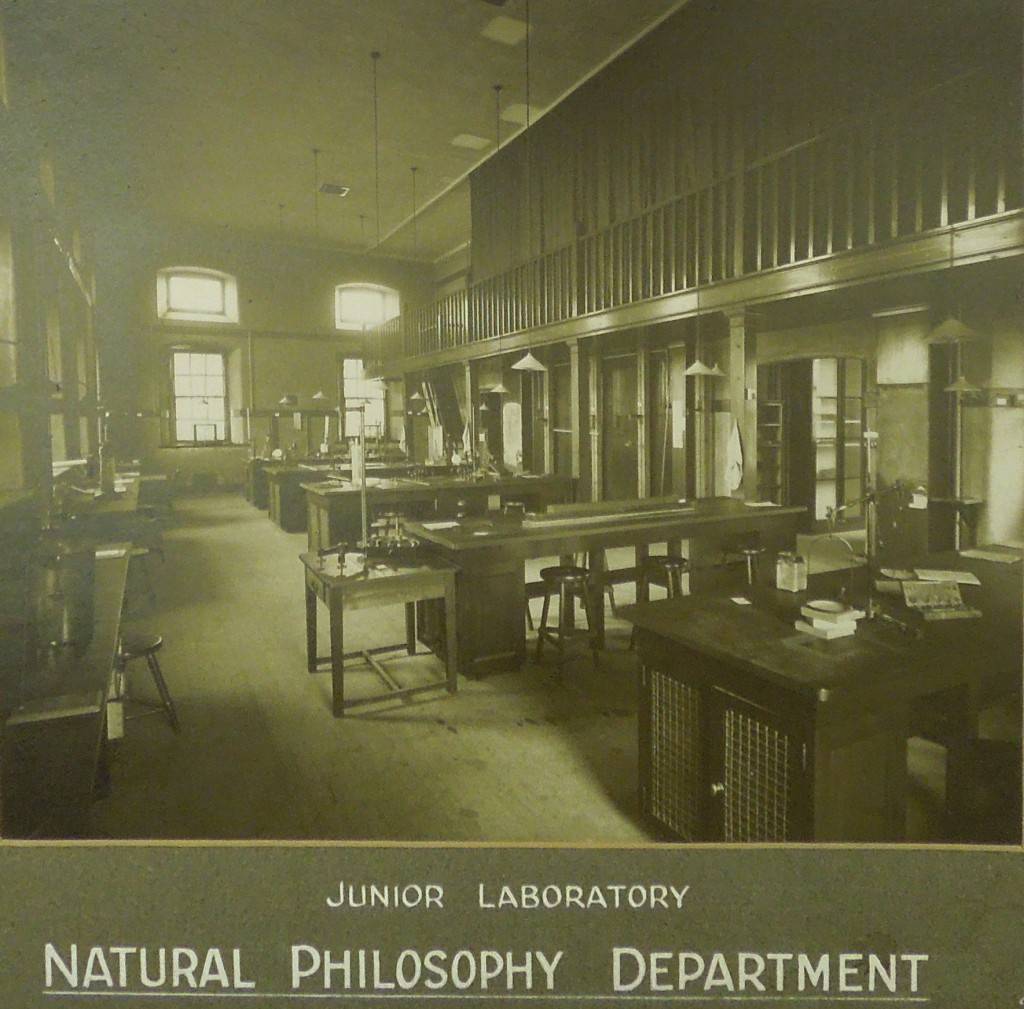

As well as all these big changes, the war also had a significant impact on the day-to-day running of both institutions, causing many small disruptions and changes. Throughout the war, the University took out various types of Aircraft and Bombardment Insurance and Fire Insurance because of the potential threat of enemy attacks, and lighting regulations were also put in place. Perhaps now more associated with the Second World War, during the Great War “blackout” regulations were also strictly enforced by the City authorities and University buildings had to ‘avoid the display of unshaded lights after 7pm’. To comply with regulations, ECA had to obscure the glass roof of the Painters’ and Decorators’ classroom and the roof lights of the Design classrooms, as they were without blinds.[22] Due to the high cost of paper, the printing of the University of Edinburgh Library Catalogue was suspended until April 1919. Building repairs, the awarding of prizes and bursaries, and the appointing of new staff all had to be temporarily suspended during the war.[23] The already outdated Departments of Science and Medicine had suffered greatly from lack of repairs or upgrades during the war, and after peace was declared the huge influx of new students intensified this problem even further; the need for a ‘large building scheme … is now more than ever urgent’. This eventually led to the creation of the new King’s Buildings campus, the foundation stone of which was laid by the His Majesty on the 6th July 1920.[24] ECA also had to make cutbacks, with the Prospectus being revised in June 1916 to minimise printing and, after special Food Regulations were introduced, the Dining Hall staff had to ‘comply with the rules laid down for Restaurants’.[25]

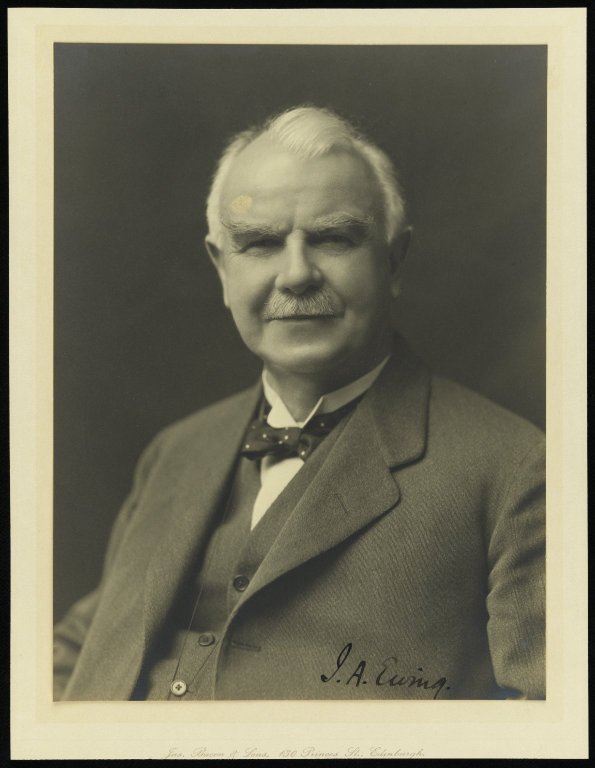

As the war continued and many students and members of staff lost their lives, both the University and ECA had to consider the most appropriate way to remember those who had fought in the war. In December 1915 the University provided money towards a memorial service at St Giles Cathedral for students who had fallen in the war, but it was not until November 1917 that a Committee was appointed to create a Roll of Honour and collect memorial photographs. The Roll of Honour was published in the spring of 1920 and contained a Roll of the Fallen, with photographs, along with a record of war service and an introductory chapter on the war work of the University. A copy was given to a relative of each of the fallen, as well as to the various public institutions to which the University Calendar was also sent.[26] ECA began their preparations slightly earlier, with a Committee beginning to put together a Roll of Honour by April 1916. There were also discussions at this time about a suitable site and design for a memorial for the fallen to be erected after the war ended.[27] The ECA memorial took the form of a mural tablet which was unveiled on the 27th June 1922, and recorded the names of five members of staff and eighty-six students who lost their lives during the Great War.[28] The University’s memorial, costing approximately £2,000 and located on the west wall of the Old College Quadrangle, was designed by Sir Robert Lorimer and was unveiled on the 19th February 1923.[29]

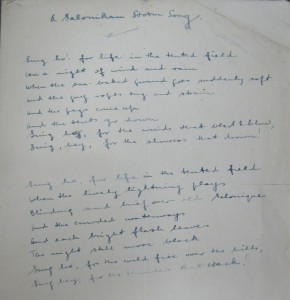

The information in the minutes of the University Court and College Committee meetings suggests that the University of Edinburgh and ECA had, on the whole, largely similar experiences of war. There is a noticeable difference, however, in the way each institution discusses the war, especially in relation to the staff and students who left Edinburgh to join the military forces. The University Court Minutes remain very formal and there is little mention of where staff or students went or what happened to them. On the other hand, the Minutes of the ECA Committee and Board meetings, which are the records most directly comparable with the Court Minutes, include far more personal information about those who signed up. In most instances, when staff applied for leave of absence the Committee also recorded which battalion they joined, and sometimes where they were stationed or if they had been involved in any major battles. Perhaps because of ECA’s smaller size, it was much easier to “keep track” of those who had joined the forces. In addition to the official Minutes, there is also a Memorial Journal, put together by Miss Agnes L. Waterston, which records in detail information about staff and students involved in the war, along with press cuttings and photographs. Waterston was also Secretary and Treasurer of the War Comforts Fund which helped to organise many fundraising activities throughout the war, details of which are often recorded in the Minutes. These records, along with the ECA Letter Books, help to build up a much more personal view of the war in which ECA appears almost as a small, close-knit community rather than a formal institution. The University records, however, present a much more clinical picture where the focus is on the official running of the institution itself rather than the people who worked and studied there. It must be remembered, however, that the University Court is an organisation which is supposed to deal with mainly financial and administrative matters, but it is interesting to see a contrast between the minutes of the University and ECA nonetheless. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, I was unable to study additional records from the University of Edinburgh – such as the Senatus Minutes – or determine whether any records similar to the ECA Memorial Journal exist; this is certainly an area of study which merits more attention.

[1] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 529, 19th July 1915’, University of Edinburgh Court Minutes, Volume XI, January 1912 – April 1916, p597; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 546, 22nd January 1917’, University of Edinburgh Court Minutes, Volume XII, May 1916 – July 1920, p110

[2] ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 6th July 1915’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.7, October 1914 to July 1915, p87

[3] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 539, 12th June 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p21

[4] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 522, 18th January 1915’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p503-4

[5] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 571, 12th May 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p476-77

[6] ‘Meeting of the College Committee of the Board of Management, 1st February 1916’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No. 8, October 1915 – July 1916, p35

[7] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 536, 13th March 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p682

[8] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 539, 12th June 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p21-22’ ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 540, 10th July 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p30

[9] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 568, 17th February 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p434

[10] ‘Letter, 20th November 1914’, Edinburgh College of Art, Letter Book, No. 14, p184

[11] ‘Minutes of Meeting’ No 527, 14th June 1915’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p569-70

[12] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 556, 17th December 1917’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p251; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 561, 6th May 1918’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p310

[13] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 571, 12th May 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p480-81

[14] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 565, 18th November 1918’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p383

[15] ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 13th March 1917’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No. 9, October 1916 – July 1918, p39; ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 11th December 1917’ Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.9, October 1916 – July 1918, p15

[16] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 550, 14th May 1917’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p 153

[17] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 545, 18th December 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p97; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 558, 18th February 1918’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p267

[18] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 546, 22nd January 1917’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p111

[19] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 520, 16th November 1914’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p487

[20] ‘Meeting of the Sub-Committee of the Board of Management, 14th August 1917’, ECA Minute Book, No.9, p4; ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 5th November 1918’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.10 October 1918 – July 1920, p9-10

[21] ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 5th March 1918’, ECA Minute Book, No.9, p27

[22] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 543, 23rd October 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p60; ‘Meeting of the College Committee of the Board of Management, 1st December 1914’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.7, October 1914 – July 1915, p22

[23] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 567, 13th January 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p402-3

[24] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 567, 13th January 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p404; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 585, 18th October 1920’, University of Edinburgh, Court Minutes, Volume XIII, October 1920 – July 1924, p1

[25] ‘Meeting of the College Committee of the Board of Management, 6th June 1916’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.8, October 1915 – July 1916, p70; ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 8th May 1917’, ECA Minute Book, No.9, p53

[26] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 532, 13th December 1915’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p637; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 577, 19th January 1920’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p623

[27] ‘Minutes of the College Committee of the Board of Management, 4th April 1916’, ECA Minute Book, No.8, p56

[28] ‘Note, March 1919’, Edinburgh College of Art, War Memorial Papers; ‘Note, February 1920’, ECA, War Memorial Papers; ‘Invitation, June 1922’, ECA, War Memorial Papers

[29] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 605, 17th July 1922’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XIII, p302; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 608, 18th December 1922’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XIII, p331

Ernst Levin (1887 – 1975)

Ernst Levin (1887 – 1975)