In March 1991 the Government of New Zealand presented Edinburgh University Library with the Library of New Zealand House, London. The New Zealand Studies Collection has recently been catalogued and is now fully accessible via our online catalogue.

One item which came to light in the process was a copy of Onward : H.M.S. New Zealand, detailing the ship’s construction and record of service in the First World War.

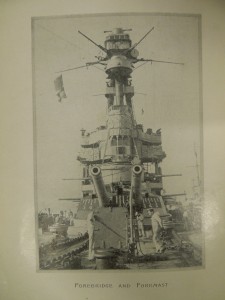

She was built by Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Co., Govan, Glasgow, being commissioned on the 19th November, 1912. The cost of her construction was met by the Dominion of New Zealand, who then gave her to the British Navy.

She had a very active wartime service record, being present at the Battle of Heligoland Bight (August, 1914); the Battle of Dogger Bank (January, 1915); the Battle of Jutland (May-June, 1916); Second Battle of Heligoland Bight (November, 1917); during 1918 she was occasionally used on escort duty for convoys sailing between Britain and Norway, and was present at the time of the surrendering of the German High Seas Fleet in the Forth, in November, 1918.

Our copy is full of manuscript annotations from its original owner, P.J. Voyzey, Wardroom Messman. He lists all the ships he served on though a naval career of 38 years, spanning both world wars. He was on board H.M.S. New Zealand from 1917 to 1919, and so, presumably, was there at the surrender of the German Fleet.

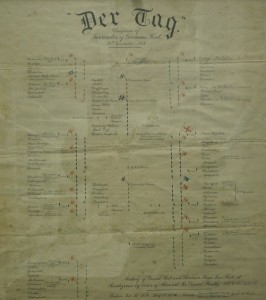

With the signing of the Armistice on 11th November, 1918, the First World War was over. One stumbling block was the Allied powers’ failure to reach an agreement on what should happen to the German surface fleet. It was the suggestion of Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss that the fleet be interned in at Scapa Flow, Orkney, Scotland, to await a decision. The Grand Fleet would guard the German ships and their skeleton crews.

Germany was instructed to have her High Seas Fleet ‘ready to sail’ by the 18th November. Admiral Beatty, aboard his flagship, HMS Queen Elizabeth, had several meetings with Admiral von Hipper’s representative, Rear-Admiral Meurer, where the terms of surrender were worked out: U-boats would surrender to Rear-Admiral Tyrwhitt at Harwich; the surface fleet would sail to the Firth of Forth and surrender to Admiral Beatty. Thereafter, the fleet would be escorted to Scapa Flow to be interned.

The surrender was executed with great formality and as a great spectacle. Our collections include this framed chart showing the position of all the ships involved. H.M.S. New Zealand is in the group in the top left-hand corner.

Von Hipper refused to surrender the fleet himself, passing on the duty to Rear-Admiral von Reuter. On the morning of 21st November the light cruiser Cardiff met the German fleet, and led it to the rendezvous with the 250 ships of the British Grand Fleet and flotillas of the other allies. In all 70 German ships sailed that day: König (battleship) and Dresden (light cruiser), suffering engine trouble, were left behind. V30 (destroyer) was extremely unlucky in striking a mine en route and promptly sinking.

The German fleet was then escorted into the Firth of Forth. Once anchored, Beatty signalled:

The German flag will be hauled down at sunset today and will not be hoisted again without permission.

POSTSCRIPT

After nine months in Scapa Flow, waiting for a final decision on the fate of the fleet, Rear-Admiral von Reuter decided to scuttle the fleet rather than let it fall into hands of the British Navy. On 21st June 1919, after months of secret preparations – welding bulkhead doors open, laying charges and disposing of vital keys – the order to scuttle was given. Fifty-two ships were sunk while twenty were beached by the British Navy.

After the war H.M.S. New Zealand took Admiral Jellicoe on a tour of naval defences throughout the British Dominions, including Australia and New Zealand. She was sold for scrap in 1922, her armaments being regarded as obsolete. Various of her guns and other equipment were returned to New Zealand for re-use, and two were placed in front of the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

It took until 1944/45 for the Government of New Zealand to finally pay off the loan used to fund the construction of the ship.

Kia ora (“be well/be healthy”): a Māori native language greeting. It also forms the half- and running-titles of the book Onward : H.M.S. New Zealand.