Following on from Archibald Campbell’s account of the Zeppelin raid on Edinburgh and Leith one hundred years ago this weekend, minutes and images from Lothian Health Services Archive (LHSA) reveal its impact on the city’s hospital services.

As Archibald noted, the raid inflicted great damage on his school, George Watson’s College, just minutes away from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh on its Lauriston Place site. The impact upon Scotland’s largest voluntary hospital was less than that suffered by the school, but still notable. Luckily, LHSA holds a comprehensive account of the effects of the bomb damage on the Infirmary in minutes of the hospital’s House Committee. The Committee met a week after the blast, on 10th April 1916 (LHB1/1/54). According to the account, the George Watson’s bomb caused windows in three wards to be broken, along with damage to side rooms and an operating theatre – miraculously, however, no staff or patients were killed.

Bomb damage to buildings near the Infirmary, 2 – 3 April 1916 (P/PL1/E/208).

In addition, an incendiary bomb was dropped on the Infirmary itself, on the boiler house, although this caused relatively little damage.

Incendiary bomb in situ at the Royal Infirmary , 1916 (P/PL1/E/021).

Like Archibald Campbell, Infirmary staff kept their own souvenir. Here at LHSA, we have this memento: a part of the actual incendiary bomb in a glass display case, which we store in our off-site store (because it is bulky rather than because it could go off!)

Incendiary bomb in glass display case (LHSA object collection, O26).

The Infirmary kept services going despite the raid, with the House Committee minutes praising medical, surgical and nursing staff, who carried out their duties ‘notwithstanding the immanence of personal danger … their individual efforts to reassure the patients did much to allay the alarm which naturally existed in the Hospital.’

The minutes record that 27 people were treated for bomb damage during the night, 12 of whom ‘were treated as in-patients, two of whom subsequently died and the remainder were treated in the out-patient department.’ The Infirmary’s General Register, which records admissions to the hospital, reflects the casualties from the night. Although the injuries to some are not explicitly stated as caused by the bomb, it is possible to have a good guess at the identity of these twelve patients and to trace the individuals who were to die from their wounds. The House Committee states that two of these patients did not survive their injuries. The General Register suggests that these unfortunates were a 45 year old carter from Grassmarket who died from perforation of the liver with a shell and an arterio-sclerotic 74 year old mason who succumbed to shock after an operation for an injury to the knee caused by the bombing.

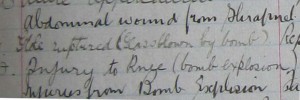

Section from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh General Register of Patients (LHB1/126/61) showing how bomb injuries were described.

One thing that those injured by the bomb had in common was their locality. Patients were centred around the old town, from the Grassmarket to St Leonards and the area of the present University of Edinburgh, making injuries such as ‘scratches to face and ear’ to people from these areas more likely than not to have been caused by effects of the raid. Others suffered injuries to the arms, legs, abdomen and head, or had eye injuries through flying glass. We can also match their addresses to bomb sites named on contemporary police and fire brigade reports.

For example, two of these patients were from 16 Marshall Street: a male tailor, who underwent surgery for a serious perforation wound to the eye; and a dressmaker, whose face had to be stitched. Both were discharged (the dressmaker on the same day and the tailor after almost four weeks). Nonetheless, they were the lucky ones in this four-storey building, housing shops, domestic dwellings, a dispensary and a school. A police report cites that six people were killed in total from the address. Three people standing in the building’s doorway and a man standing across the street were amongst the fatalities, according to the fire brigade account of the night.

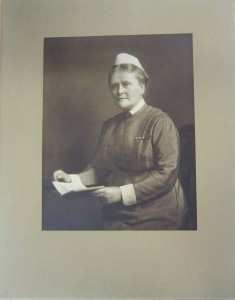

However, although no staff were injured in the explosion, the House Committee minutes point to its possible psychological effects. The Lady Superintendent of Nurses, Miss Annie Warren Gill, was worried that, if another raid should occur, members of her staff could be ‘rendered unsuitable for duty through nervousness – some of them having suffered considerably that way on the recent occasion.’

Annie Warren Gill, Lady Superintendent of Nurses, 1907 – 1925 (LHSA photography collection).

Committee members also showed concern at the lack of warning given for the attack to Infirmary officials, beyond the regular lowering of lights. In preparation for an increase in casualties following another attack, proposals were made for emergency staffing from existing medical and surgical teams.

The main part of the meeting was signed off with approbation for the enemy’s conduct, ‘the recklessness of which while dooming it to military failure endangered the lives of the inmates of an Institution whose doors have at all times been open to the suffering sick of all nations.’

Louise Williams, Archivist, LHSA

An earlier story about the attack can be read here: I: A School student walks among the wreckage