In this month’s edition, Louise, Archivist in Lothian Health Services Archive (LHSA), finds a different view of the First World War….

Ernst Levin (1887 – 1975) was a German-born neurologist who first came to Edinburgh in 1933 to work with neurosurgeon Norman Dott in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. Since Levin was Jewish, the Nazi rise to power meant that he could no longer work in his then-home of Munich, where he had just received a Chair in neurology at the city’s University.

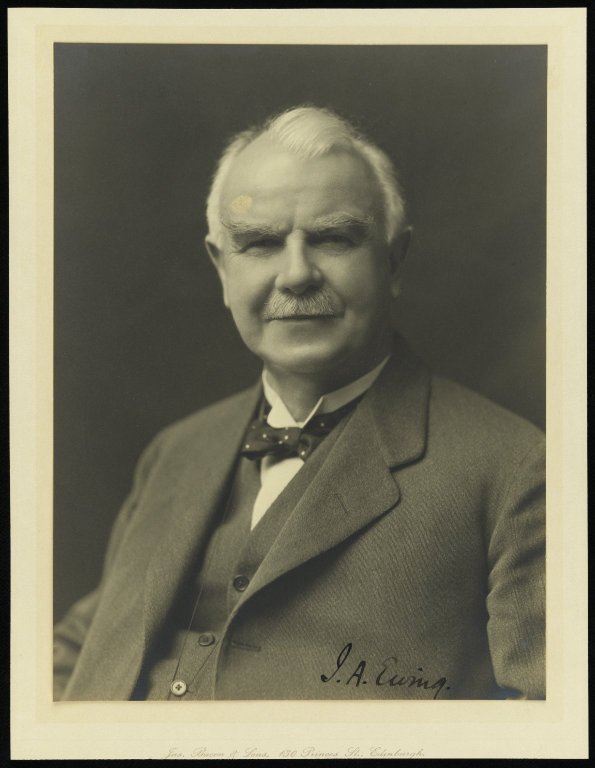

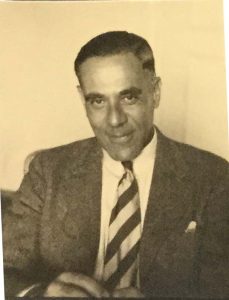

Ernst Levin (1887 – 1975)

Ernst Levin (1887 – 1975)

We knew about Levin’s medical work in hospitals across the city and for the German consulate in Scotland through his medical papers, donated to LHSA in the 1970s. However, although we had a record of Ernst’s career, we knew little of his time in Germany or his experiences as an émigré, leaving a lot of blanks when interested researchers asked to know more about the man behind the archive.

In 2015, I was given the opportunity to acquire Levin’s personal papers for LHSA – letters, photographs and mementos that added to the clinical profile we already held. This was a first for us in combining private and career records to give a more complete picture of a prominent personality in Edinburgh’s medical life.

Through this new collection, I learnt that Levin served during the First World War and later, along with his wife Anicuta Belau, had a wide circle of friends in the artistic movements of the decadent Weimar Republic. With the Nazi rise to power, Levin came to Edinburgh, subsequently joined by Anicuta and their daughter, Anna. Levin (like many other European exiles) was interred (in the Isle of Man) during the Second World War – but still returned to live the rest of his life in Edinburgh.

One of the first things that I noticed about our new donation was a group of photographs and mementos from the First World War, when Levin served as Assistant Surgeon of the Reserve of the Bavarian Infantry Regiment. These images from the German lines were extremely striking, and gave an immediate view of the trenches that are rare from British troops. Although smaller cameras were popularising photography as a hobby by the time of the First World War, the British Army had imposed restrictions on private camera use by 1916. In contrast, personal photography was tolerated more on the German side. It appears that Levin was a keen photographer, and noted chemicals used in the development process on his photograph envelopes. There are a large number of First World War images in the collection, from photographs of the German lines:

… to soldiers relaxed and enjoying themselves:

As a first for us, LHSA has also acquired images of German field hospitals thanks to Levin’s collecting:

What really sticks out about Ernst’s First World War archive is the mixture of battlefield images and snatched moments of life for civilians under occupation – something that is reflected in his photography:

… but also by handmade postcards which were intermingled with his war memorabilia:

The postcards are signed, but we cannot be sure whether they were created under a pseudonym by Ernst himself or by an acquaintance. The word ‘Postkaart’ on their reverse may imply that they were drawn in Holland or Belgium, though:

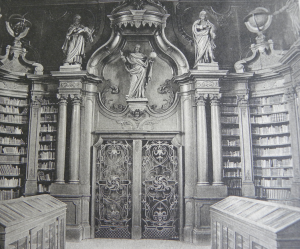

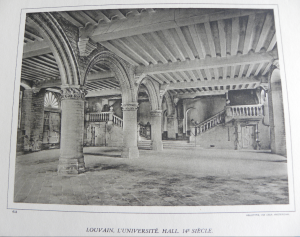

We can guess where Ernst may have been stationed on account of the paper memorabilia he collected, from postcard books of places like Bruges and Tournai to maps of the front-lines:

As a medic, Levin far from escaped the dangers of the Front. In fact, he won a Military Medical Medal for his heroism in the Battle of the Somme. In August 1916, Levin was ordered to set up a dressing station in Cléry. Not only did he achieve this in an exposed area without artillery protection, but also showed bravery under fire when the station was shelled. The following is taken from Bavaria’s Golden Roll of Honour, compiled from the Bavarian War Archive:

“Whilst everyone took what shelter they could from the artillery fire, Dr Levin, hearing a wounded man cry out, immediately went to the aid of the casualty despite the firing and at the risk of his life. He bandaged the wounds and carried the man to the dug-out. Throughout the Battle of the Somme, Dr Levin distinguished himself by his spirit of sacrifice, his calmness and level-headed-ness and his strong sense of duty.”

Ernst Levin in uniform

It is lucky that a good proportion of this war archive is largely visual – most of Levin’s personal collection is written in German. There are, for example, bundles of letters like this one, sent home to Munich through the German military mail system, Feldpost:

And it is this language barrier that, at the moment, we are looking for ways to overcome, from involving academics to better understand the content of Levin’s archive to tracing the content of the collection through methods that do not involve deciphering the older-style German script in which manyof the letters are written. However, the visual clues I can decipher have already given me a privileged view behind the German lines.

All images from LHSA accession, Acc15/001.