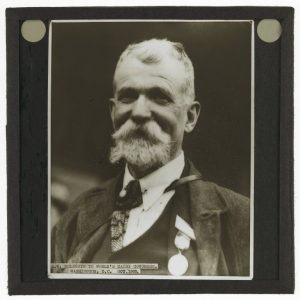

Professor Robert Wallace, from the glass slide collection partially amassed by him (Coll-1434/3200)

Robert Wallace (1853-1939) is not a widely-known name today, although in his time he was an important agriculturalist who travelled the world. He was Professor of Agriculture and Rural Economy at the University of Edinburgh between 1885 and 1922, and established the Edinburgh Incorporated School of Agriculture. Edinburgh University Library Special Collections holds some material relating to Wallace, namely, a collection of glass slides partly amassed by him and some written material. Among these papers is a collection of Wallace’s copies of a number of letters sent to President Woodrow Wilson during the First World War.

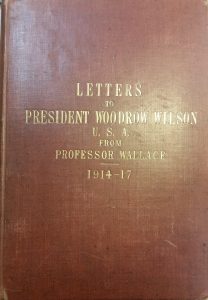

‘Letters to President Woodrow Wilson…’ (Gen.867F)

Over the course of 27 letters dating between 30 August 1914 and 3 April 1917, Wallace addresses the President on the perceived dangers to allied prisoners of war under the system of “frightfulness” (a term which was used to describe an assumed military policy of the German Army towards civilians in World War I, particularly during their invasion of Belgium in 1914). Wallace also expresses concern about the dangers of starvation to the Belgian people, and about what course of action America, who was then neutral, ought to take. In his first letter, Wallace sets out his aims:

My object is to inform you of the root-causes of the present war and of the nature of the German autocracy with which the civilised world is confronted, for it is to my mind certain that America is destined to play an important part in that compact among the leading nations which must make a gigantic war in the future an impossibility.

Wallace enclosed a number of press cuttings and pamplets, such as Morals and German Policy by Arthur Conan Doyle and an article on the Neutrality of the United States in relation to the British and German Empires by Joseph Shield Nicolson, then Professor of Political Economy at the University of Edinburgh.

These letters were by no means Wallace’s first brush with American political figures. He had visited the United States on a number of occasions as part of his work, and on a visit in 1898 he met James Wilson, Minister of Agriculture at Washington (who had emigrated from Scotland aged 18 and, it was discovered, happened to be related to Wallace). Wilson introduced him to President McKinley, the 25th President of the United States, who spoke warmly to Wallace of Britain’s support of America during the Cuban War. Wallace clearly hoped that his letters to the 28th President would encourage a return of this favour.

However, although the White House confirmed that his letters had been received, it appears that Wallace was never granted a response from the President himself. Undeterred, he continued to collect and send press cuttings and articles, and as the war progressed his tone became more urgent. In a letter dated 5 February 1917, Wallace expressed his “profound disappointment and my public, as well as private, regret” at the President’s address to Congress on 3 February that his country was “sincere friends of the German people and earnestly desire to remain at peace with the Government which speaks for them.” This statement was made following Germany’s proposal to form a military alliance with Mexico in the event of the US entering the war (the ‘Zimmerman telegram’), and many were critical of Wilson’s minimal reaction. After the sinking of several American ships, however, Wilson called a cabinet meeting on 20 March, in which America’s entry into the war received a unanimous vote.

Wallace himself did not necessarily believe that entering the war was the desired solution. In his final letter to the President (which he titled his “final supreme effort”) dated 3 April 1917, Wallace urged Wilson to commission all German and Austrian ships in USA harbours to carry food to Belgium, and suggested that America should unite with the Chinese Republic as a deterrent to Germany.

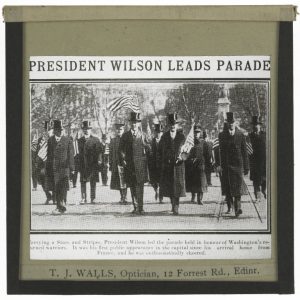

‘President Wilson Leads Parade’ – a glass slide from the collection partially amassed by Wallace (Coll-1434/3261)

Yet on the following day, a declaration of war by the United States against Germany passed Congress by strong bipartisan majorities.

In 1919, Woodrow Wilson spent six months in Paris at the Peace Conference, where he was a staunch advocate of the creation of a League of Nations. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in the same year. Wallace published his letters to Woodrow Wilson in book form in 1931.

Although Woodrow Wilson’s reaction to Wallace’s letters remain unknown, they provide a fascinating insight into the subject of America’s entry in the First World War, as well as an unusual insight into Wallace’s personality against a backdrop of international conflict.

Clare Button

Project Archivist