Contributor: Murdina and Effie MacDonald, Psalm 118 to ‘Coleshill’

Fieldworker: Thorkild Knudsen

Reference: SA1965.031

Link to recording on Tobar an Dualchais

Response: Clare Button

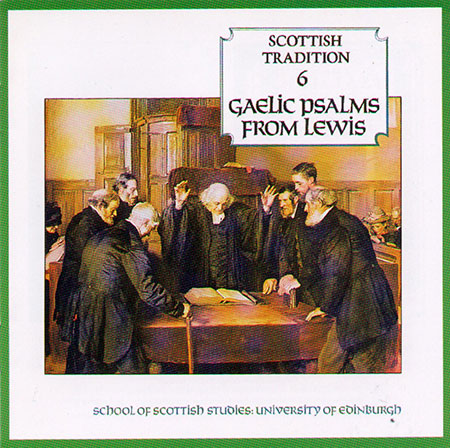

Visiting the Isle of Lewis with my parents at age fifteen seemed the ideal chance to use my newly acquired pieces of Gaelic. Back home in England I was a fervent convert, listening to all the Gaelic music I could find and devouring a book titled (more than a little misleadingly, as it turned out) Scottish Gaelic in Three Months. Thrilled as I was to hear the language around me on the streets of Stornoway, I lost the bottle to try it myself, save for a shyly squeaked ‘madainn mhath’ to a lady behind the counter in a charity shop. Bolstered by her kind reaction, I thought to repay her by purchasing something, and my eye was caught by a record titled Gaelic Psalms from Lewis, the cover emblazoned with J.H. Lorimer’s dramatic painting The Ordination of Elders in the Scottish Kirk.

Closer inspection revealed that it was Volume 6 in Greentrax’s Scottish Tradition Series, which showcased recordings from the School of Scottish Studies, a new name to me at that time. I hardly knew what to expect, but it was only twenty pence, and would just about fit in our suitcase. I suspect the lady behind the counter was somewhat bewildered to see this earnest English teenager expressing an interest in the devotional singing of her island.

It was around a month or two before I played the LP on my dad’s record player, but when I did, my musical landscape was changed forever. I had heard sacred music before, of course, but nothing like this, with the psalm being ‘lined out’ by the precentor, and the congregation following after in a heavily ornamented style, each person at their own pace. The effect was an ocean of sound, both alien and familiar, human voices locked in private devotion yet joined in communal worship.

I loved the richly dramatic congregational recordings, but I was especially struck by the singing of two sisters, Murdina and Effie MacDonald, of Balantrushal, north west Lewis. Recorded at their home in 1965 by Thorkild Knudsen, a Danish musicologist then on the staff of the School of Scottish Studies, they intone verses 15-23 of Psalm 118 to the tune ‘Coleshill’, their brittle voices trilling, soaring and swooping together in two barely separable strands. ‘Guth gàirdeachais is slàinte ta / am pàilliunaibh nan saoi…’ Their singing is particularly touching because it is domestic, sisterly, intimate. The notes to the recording mention that, although it was quite unheard of for women to precent, they may often ‘be heard singing Gaelic Psalms while at household chores.’ Now, years later, with many recordings of the MacDonald sisters available online via Tobar an Dualchais, the extent and depth of their skill at psalm singing can be truly appreciated.

A year or two later, I heard the same recording sampled by Martyn Bennett on another album which changed my life, Grit (2003). In the sleeve notes, Bennett tells the story of travelling to Balantrushal to see Murdina, then in her late eighties, to get her blessing to use the recording. She confided to Martyn her own initial misgivings back in the 1960s on recording these religious songs, a confession which he found reassuring. Of the resulting composition, ‘Liberation’, Martyn wrote:

‘I could not find any other way to express the profound feeling of losing faith, and the determination to find it again.’

It is both touching and strange to think of the sisters giving their blessing to this epic mashup of their voices with clashing rave beats, euphoric sonic whirls and Michael Marra’s best (and, I suspect, his only) attempt at being a minister. The track is radically different from Murdina and Effie’s world, but it does, I think, retain the kernel of purity found in Knudsen’s original recording.

Now, many years later, I have been entranced by sacred music of all kinds, from the astonishing Canu Pwnc tradition of Wales, to the heart-bursting ecstasy of Sacred Harp, to the simple grace of medieval plainchant, but the billowing swells of the Scottish Gaelic style hold a unique magic. My Gaelic may still not be much improved, but this recording grows with me all the time.

Clare Button is Archivist at Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London.

Listen to Murdina and Effie MacDonald here: http://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/fullrecord/67880/1

More about Martyn Bennett here: https://realworldrecords.com/artists/martyn-bennett/

Find out about the Gaelic Psalms from Lewis here: http://www.greentrax.com/music/product/Various-Artists-Gaelic-Psalms-From-Lewis-Scottish-Tradition-Series-vol-6-CD