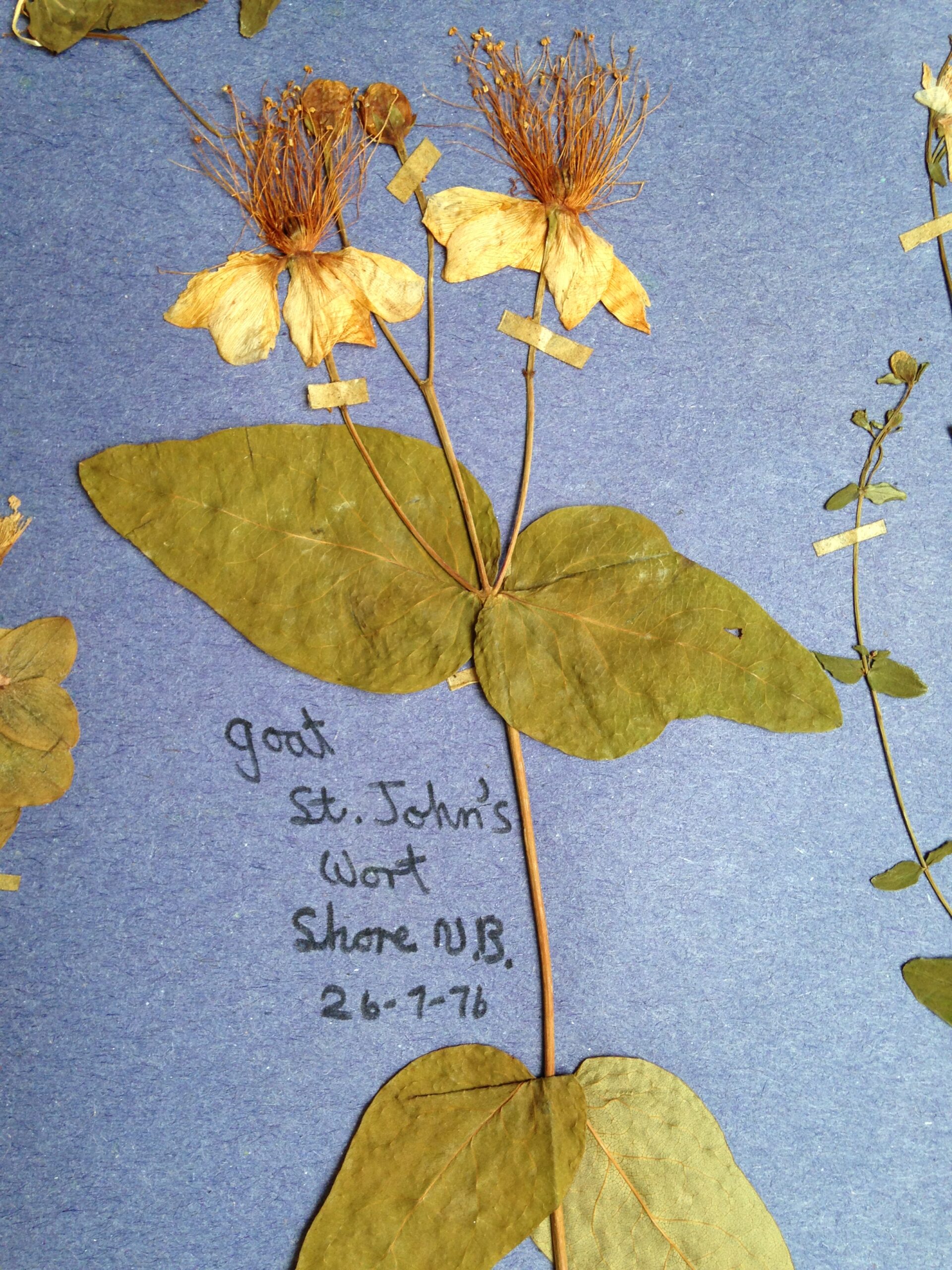

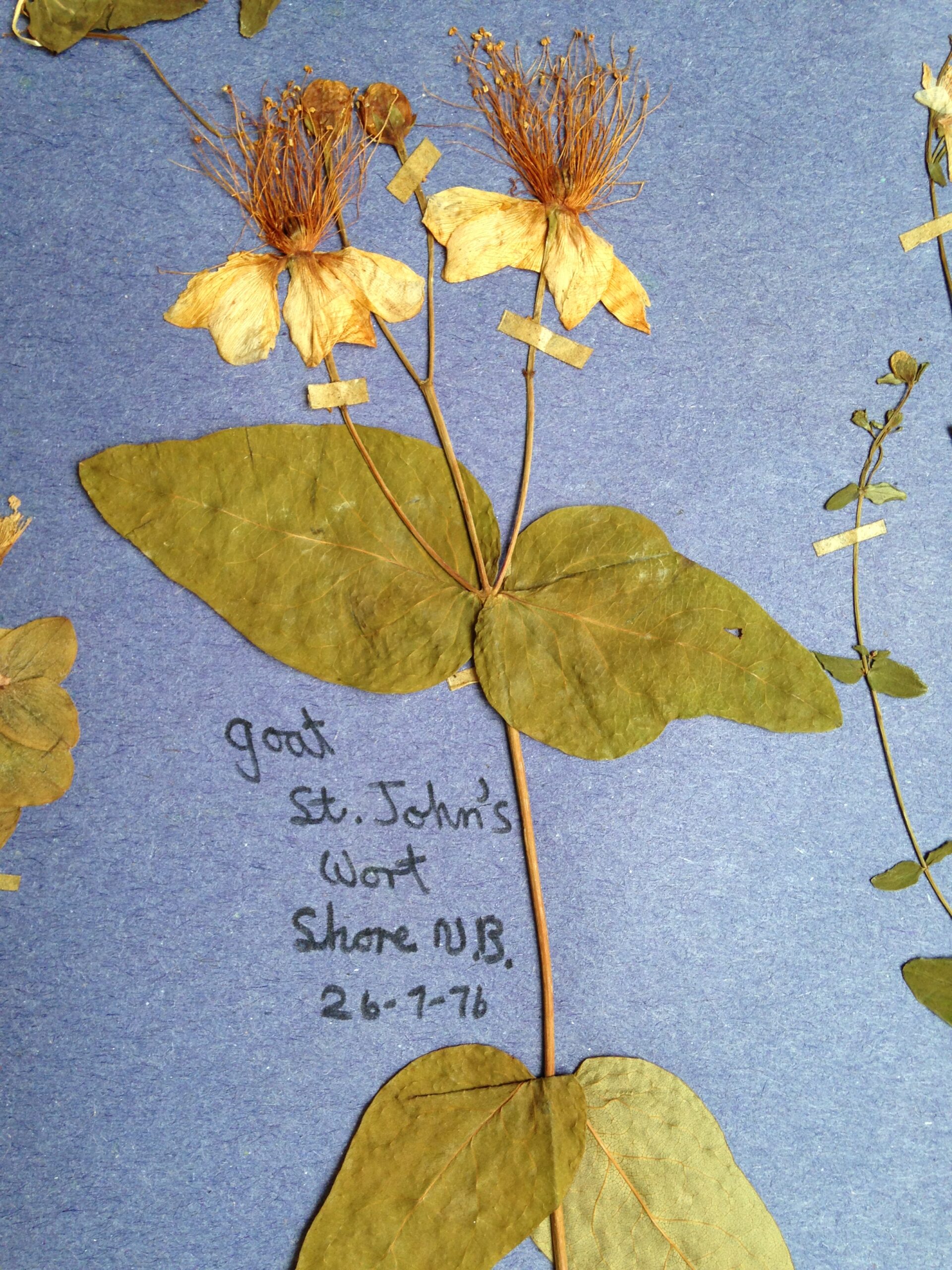

Manuscript: The Joan Clark Collection

Response by: Elaine MacGillivray

Out of a thousand possible options, I have chosen to respond to the manuscript collection of Scottish botanist Joan W. Clark (1908-1999) – in particular, her wildflower specimen books

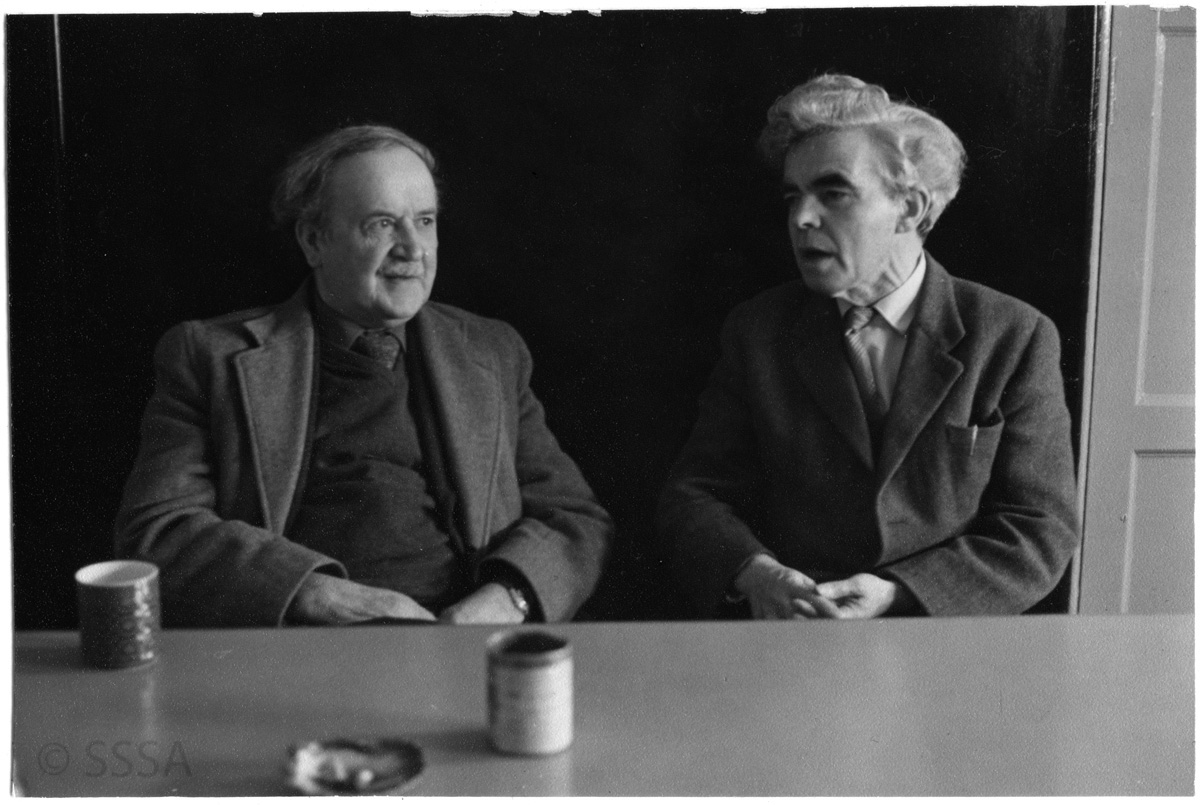

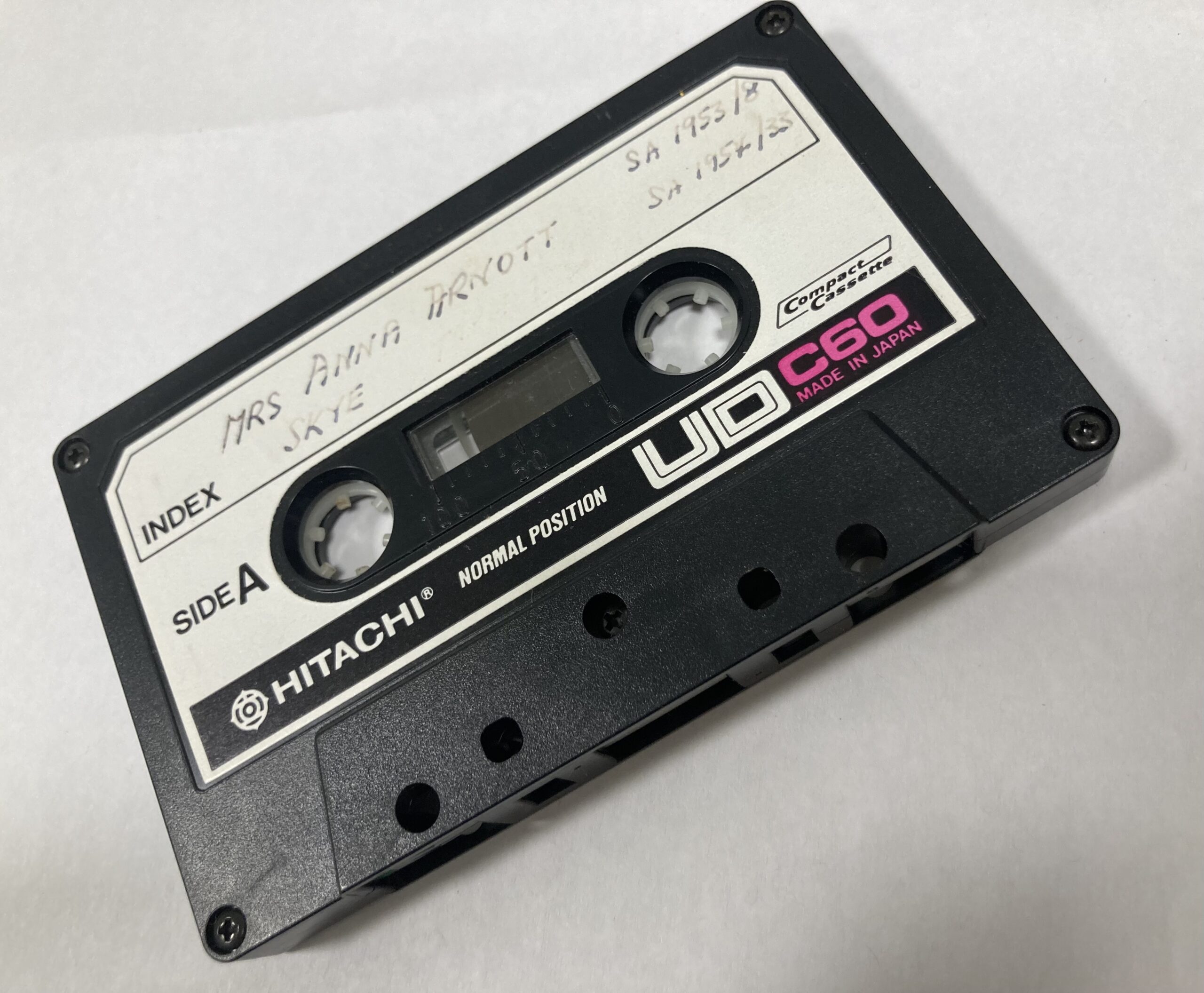

Pressed plant specimen, ‘Water Speedwell’, collected by Joan Clark from a ditch on North Uist, August 1976 (SSSA: Joan Clark Collection)

Joan Wendoline Clark grew up in Kincardineshire and Sussex. Fluent in French and German, skilled in shorthand and a trained typist, she worked for a time at the Foreign Office in London and at the British Embassy in Paris. In the 1930s she returned with her Scottish husband to Scotland and together they settled in Lochaber, where she remained until her death on 6 July 1999. Shortly after her death, her daughter, Anna MacLean kindly gifted Joan’s manuscript collection to the School of Scottish Studies Archives. The collection includes her correspondence and botanical research notes dating from the 1970s right up until 1999, along with three specimen books containing almost 350 pressed wildflowers collected around Onich, Ballachulish, North Uist and Glencoe in around 1976.

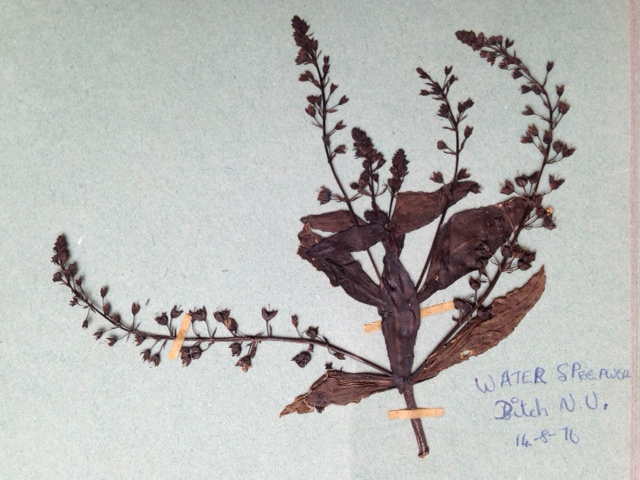

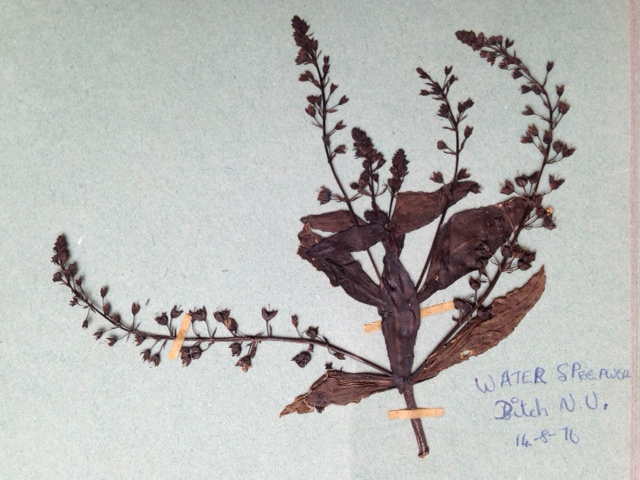

Pressed plant specimen, ‘Bitter Vetch’, collected by Joan Clark at [B]allachuil[ish], May 1976. (SSSA: Joan Clark Collection)

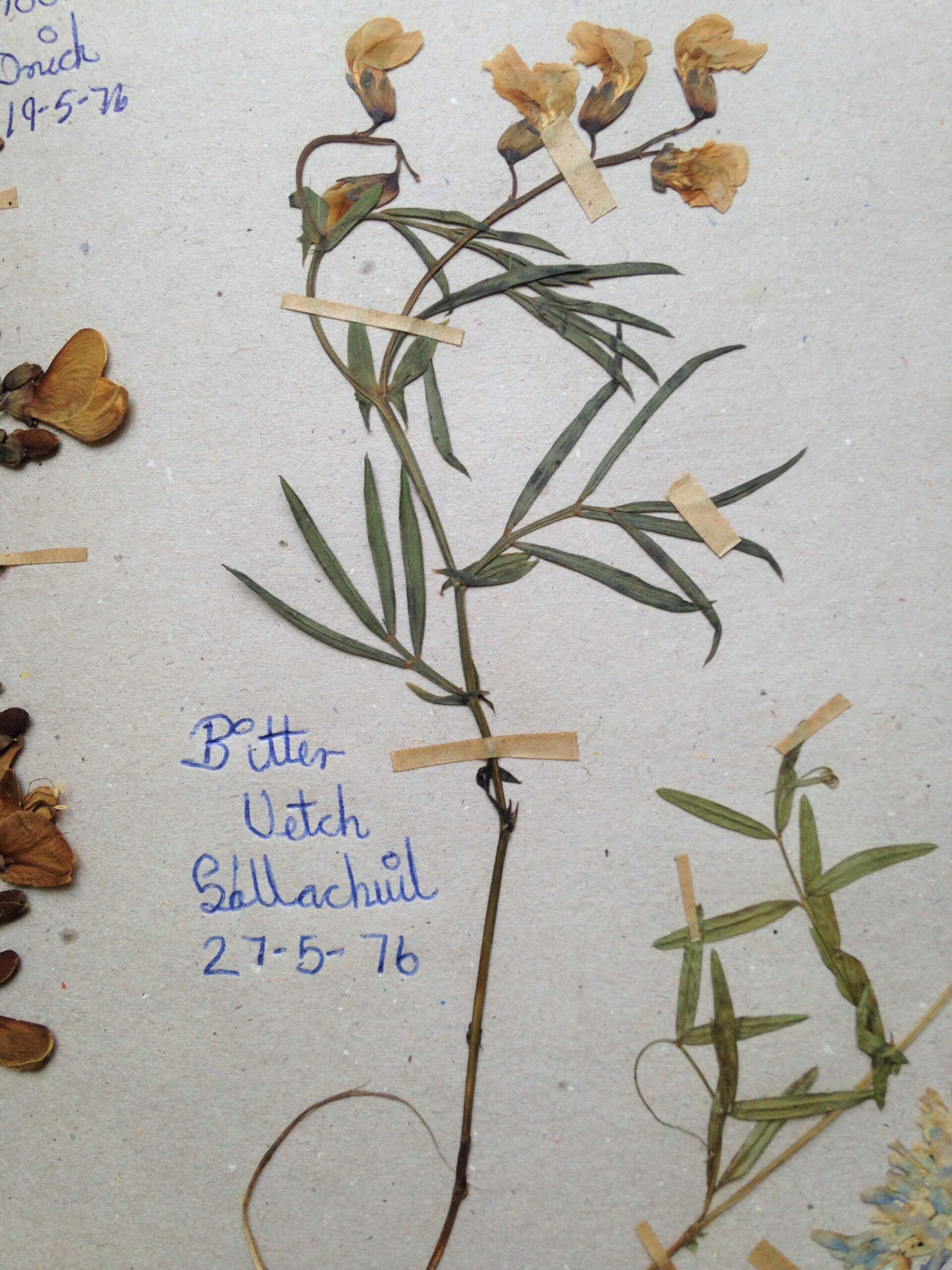

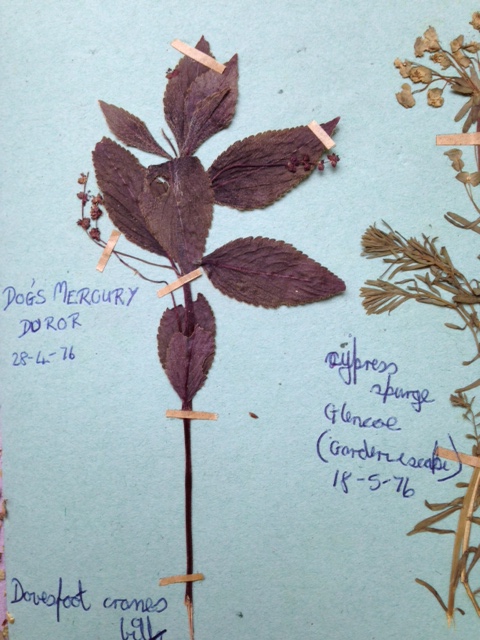

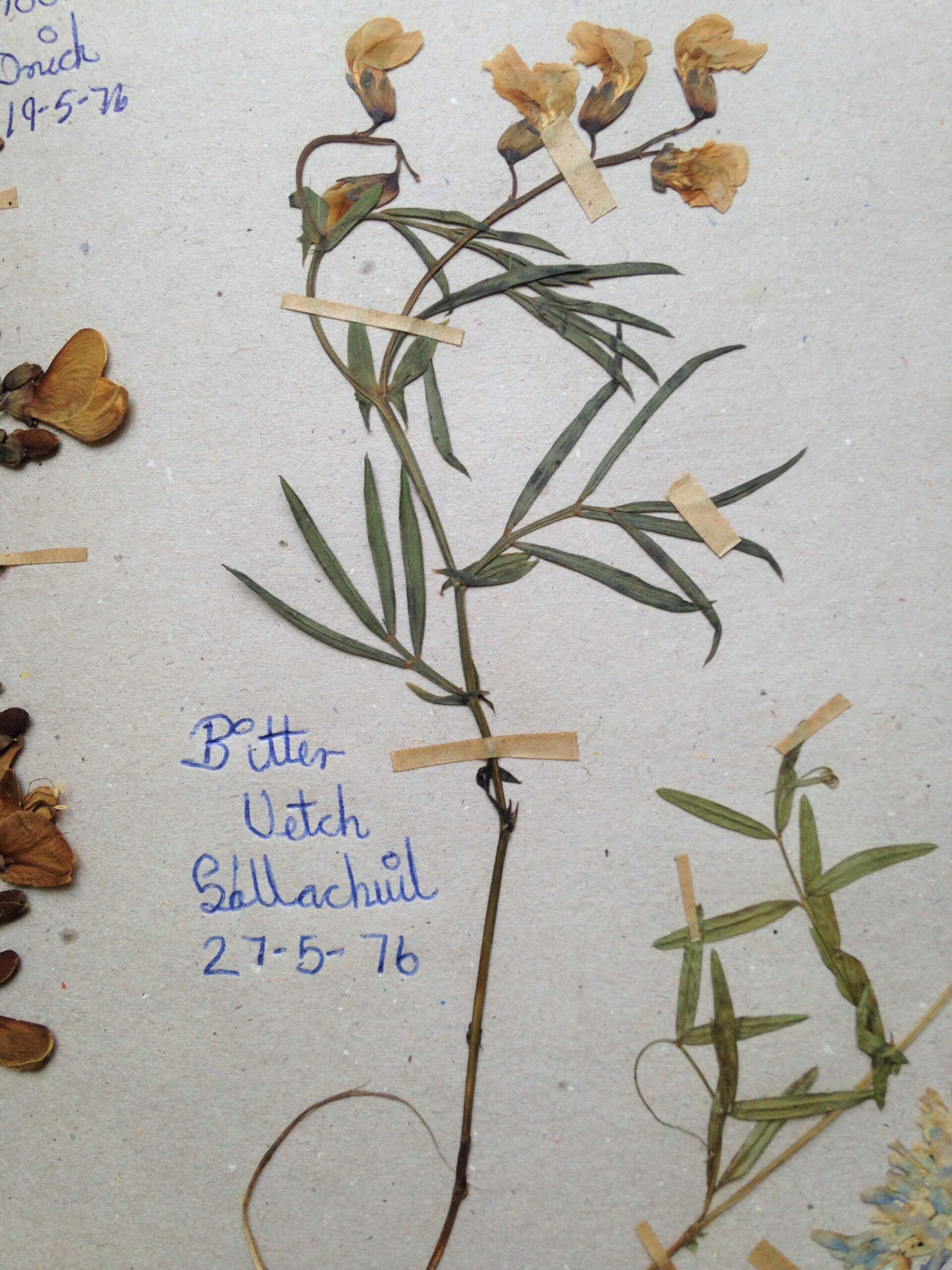

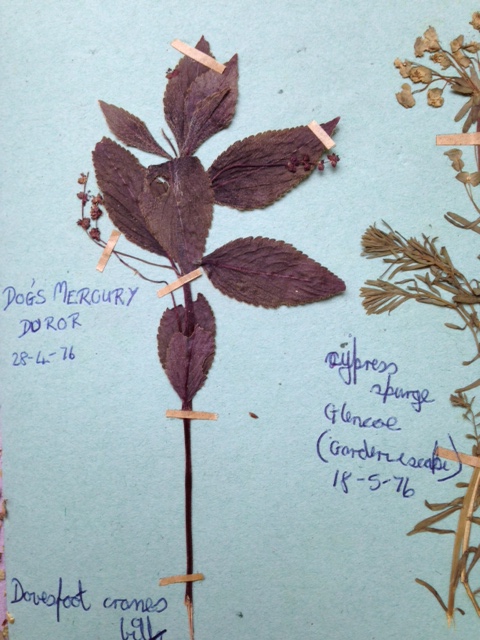

Joan Clark’s wildflower specimen books are made up of three A4 sized sugar paper leaved scrapbooks. Turning the pages, I found each leaf contained between one and three pressed wildflower specimens. Bedstraw, iris, sea pinks, sundew, dog’s mercury and so many more are all represented, carefully laid out and attached with tiny strips of paper glued at either end. Beside each specimen the name of the plant, the location it was found, the date collected and additional notes are recorded in blue or black ink. The addition of this metadata means that the specimen books are not purely aesthetic but also scientifically valuable.

Joan Clark’s manuscript collection is testament to her incredible contribution to botanical science. Her meticulous and painstaking research informed Richard Pankhurst and J. M. Mullin’s Flora of the Outer Hebrides (1991), and she collaborated with Ian MacDonald of the Gaelic Book Council to publish Gaelic Names of Plants / Ainmean Gàidhlig Lusan (1999). Many have paid tribute to her calibre as a botanist, not least the renowned and respected botanist A. C. Jermy of the Natural History Museum (Watsonia, 2000).

Pressed plant specimen, ‘St John’s Wort’ (also known as Goat Weed), collected by Joan Clark from the shore at North Ballachulish, July 1976. (SSSA: Joan Clark Collection)

Jenny Sturgeon wrote in her response to Alan Bruford’s recording of Tom Tulloch (11 Jun 2021), “local names for flora and fauna root us to where we come from and there is a cultural history and identity associated with them.” Growing up on the west coast of Argyll, I was taught the names of the local wildflowers there by my mother and grandmothers. During my post-graduate studies in Liverpool, my mother once sent me a snapdragon – collected, pressed and placed between two pieces of tissue paper in a card. On the card was a scribbled note: “snapdragons are out and so I thought you would like to see one!” For me, and for many, flora and fauna offer up a very tangible connection to people, place and time.

Pressed plant specimen, ‘Dog’s Merury’, collected by Joan Clark at Duror, April 1976 (SSSA: Joan Clark Collection)

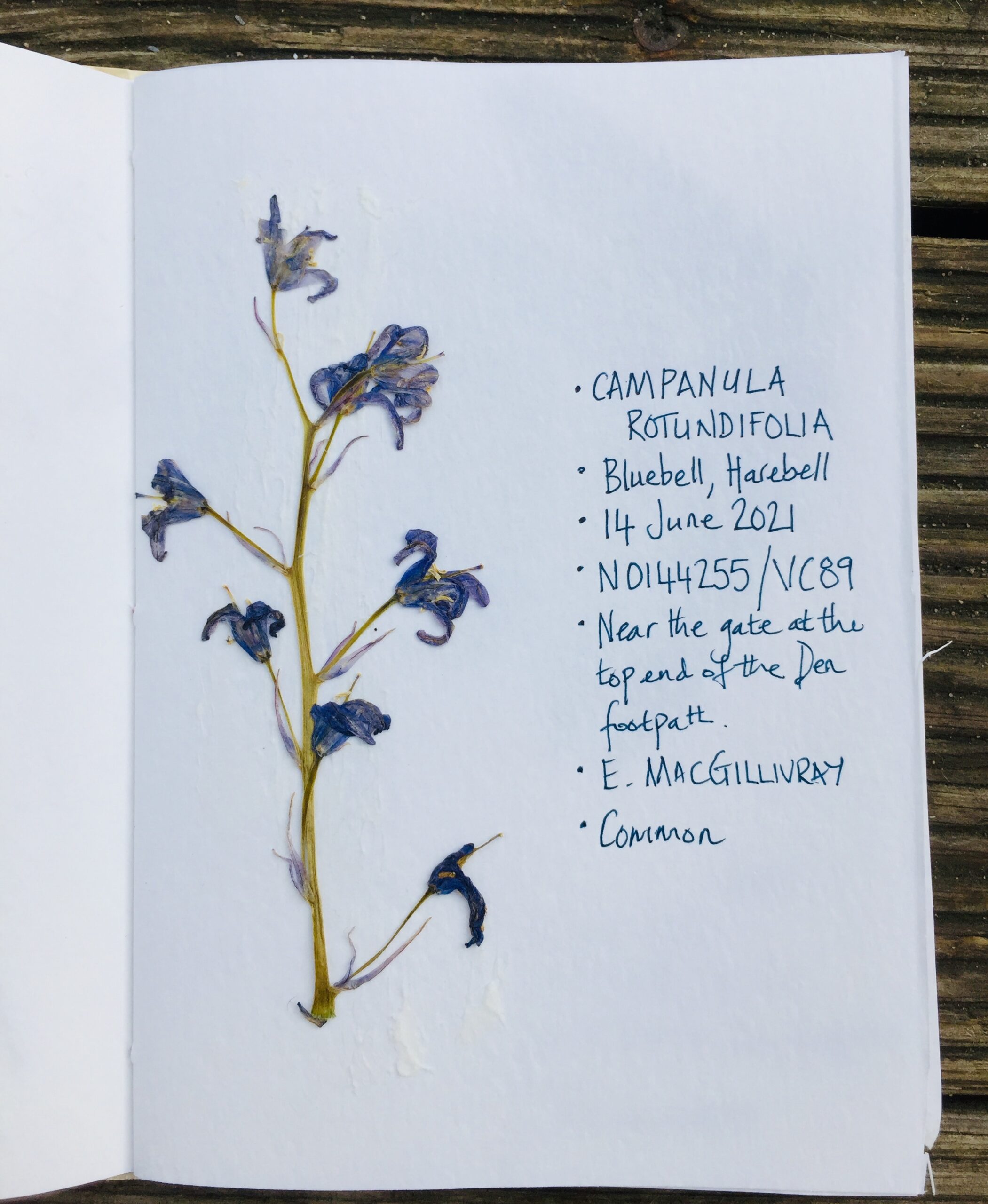

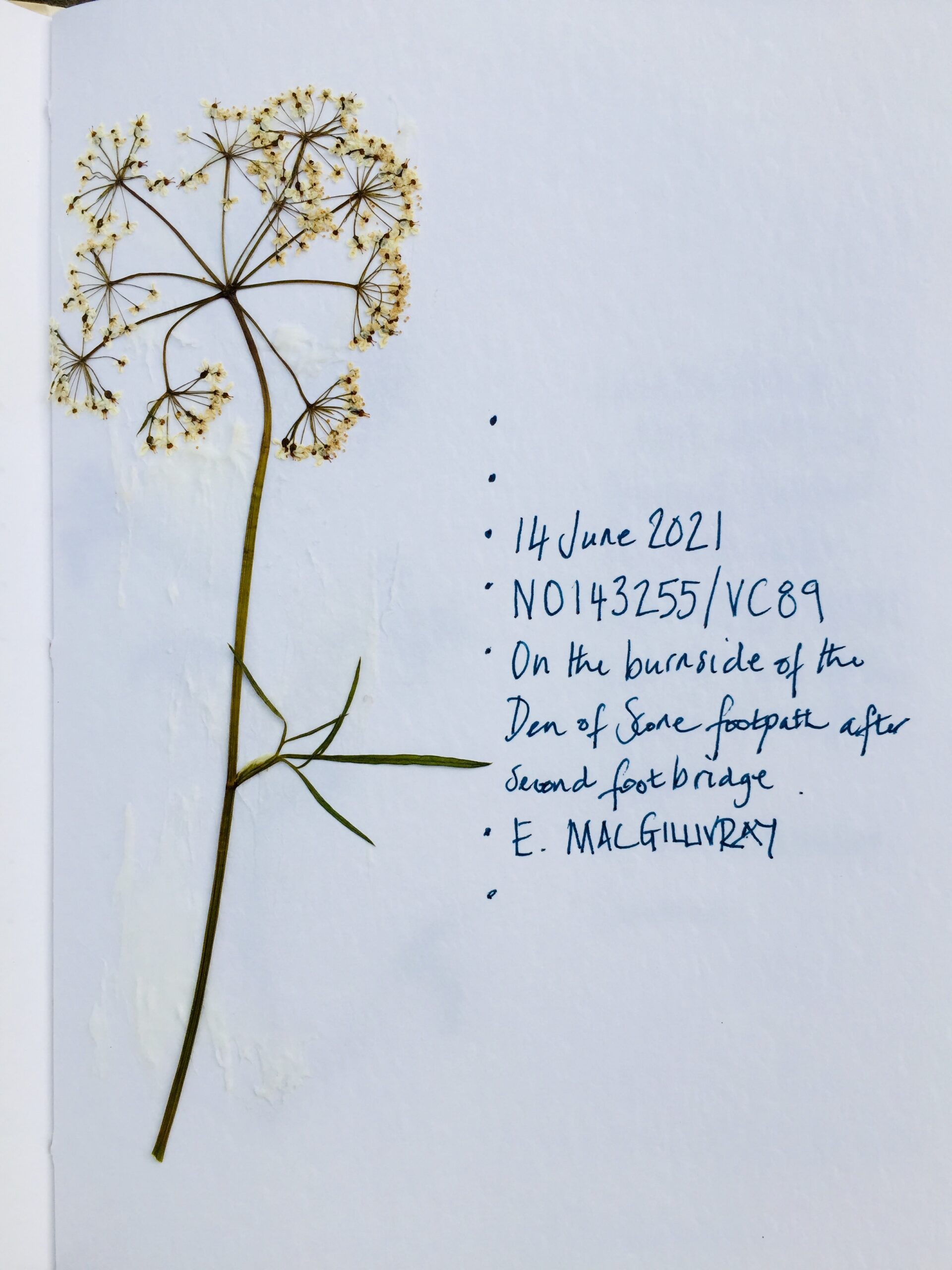

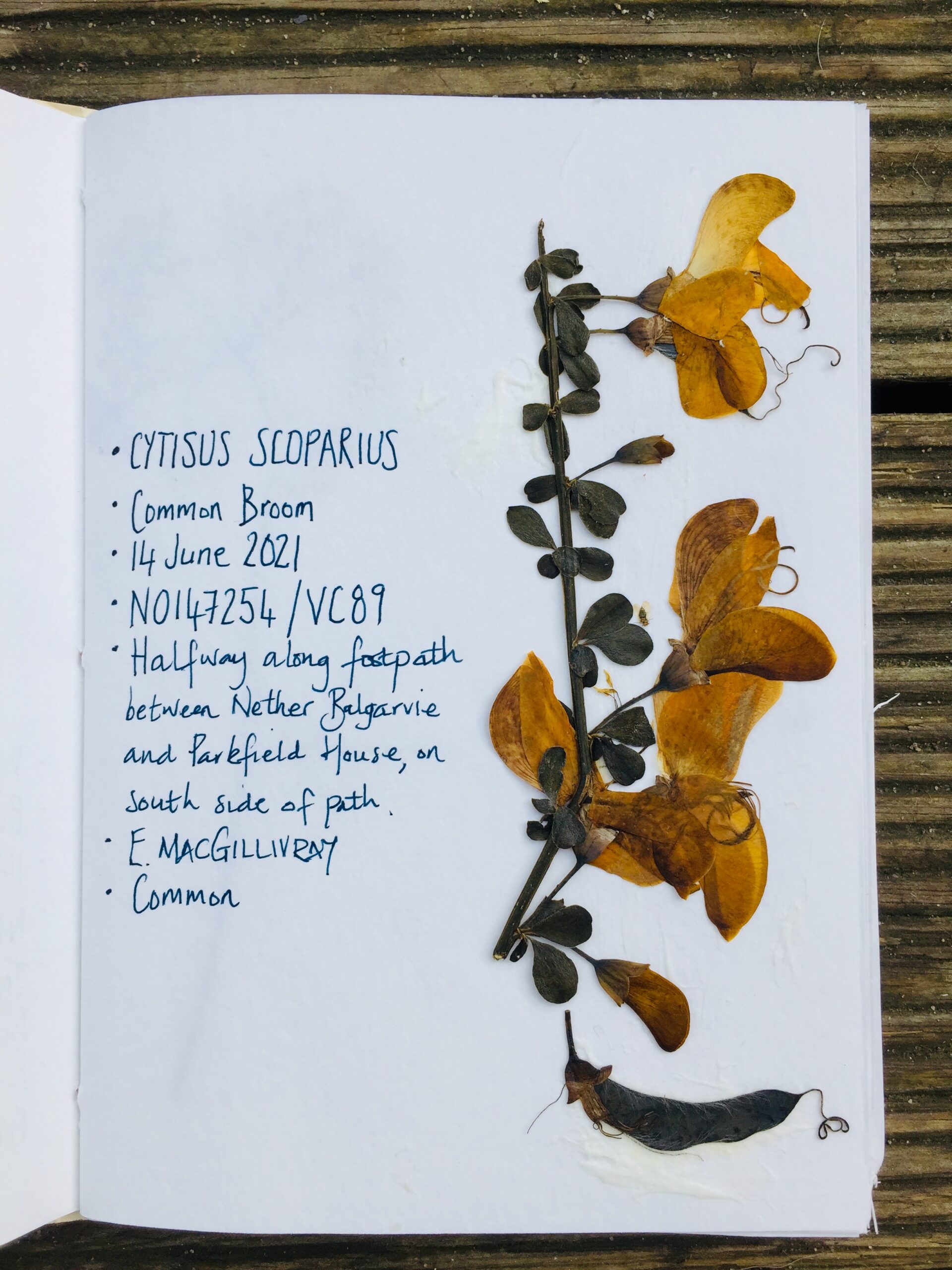

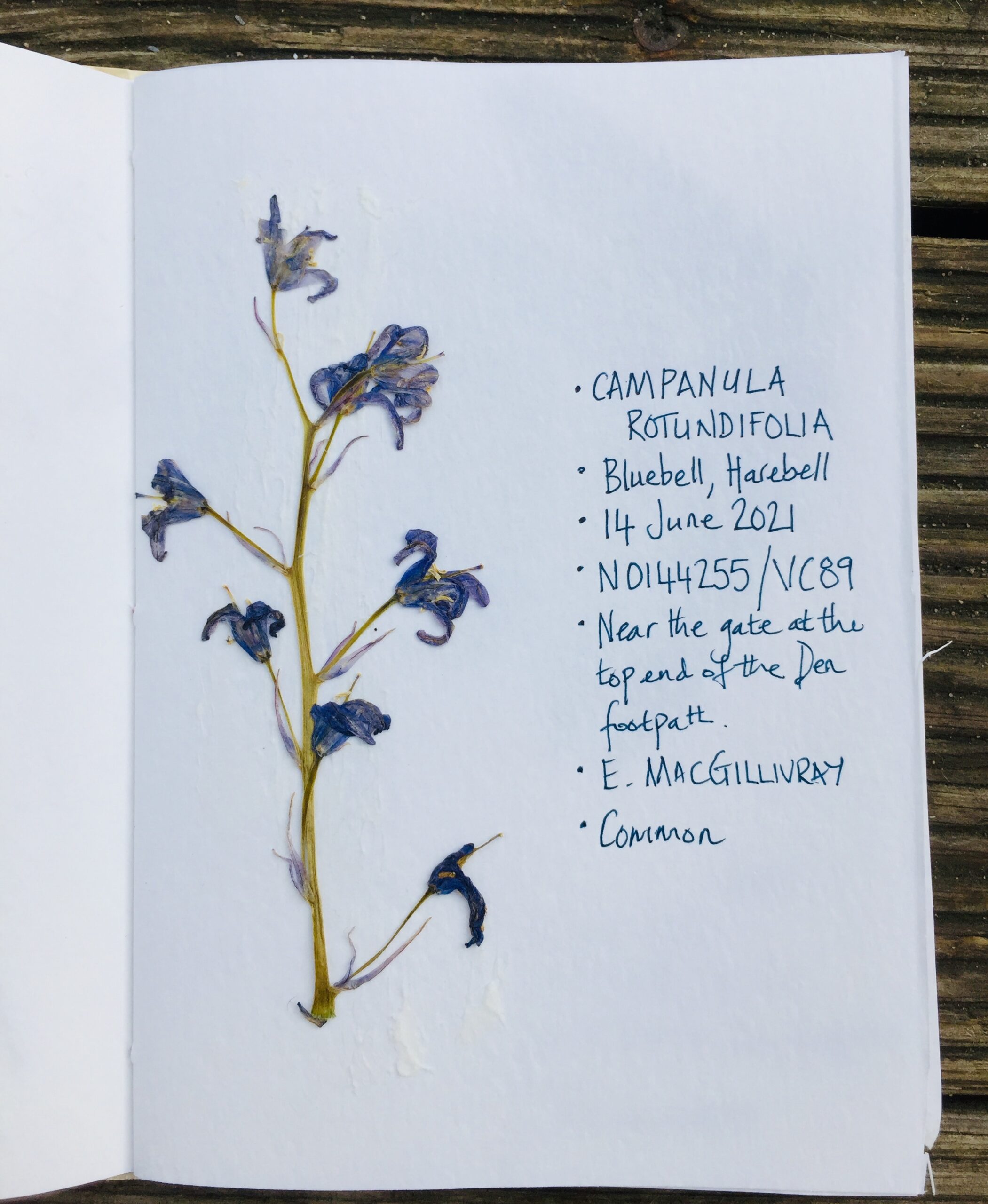

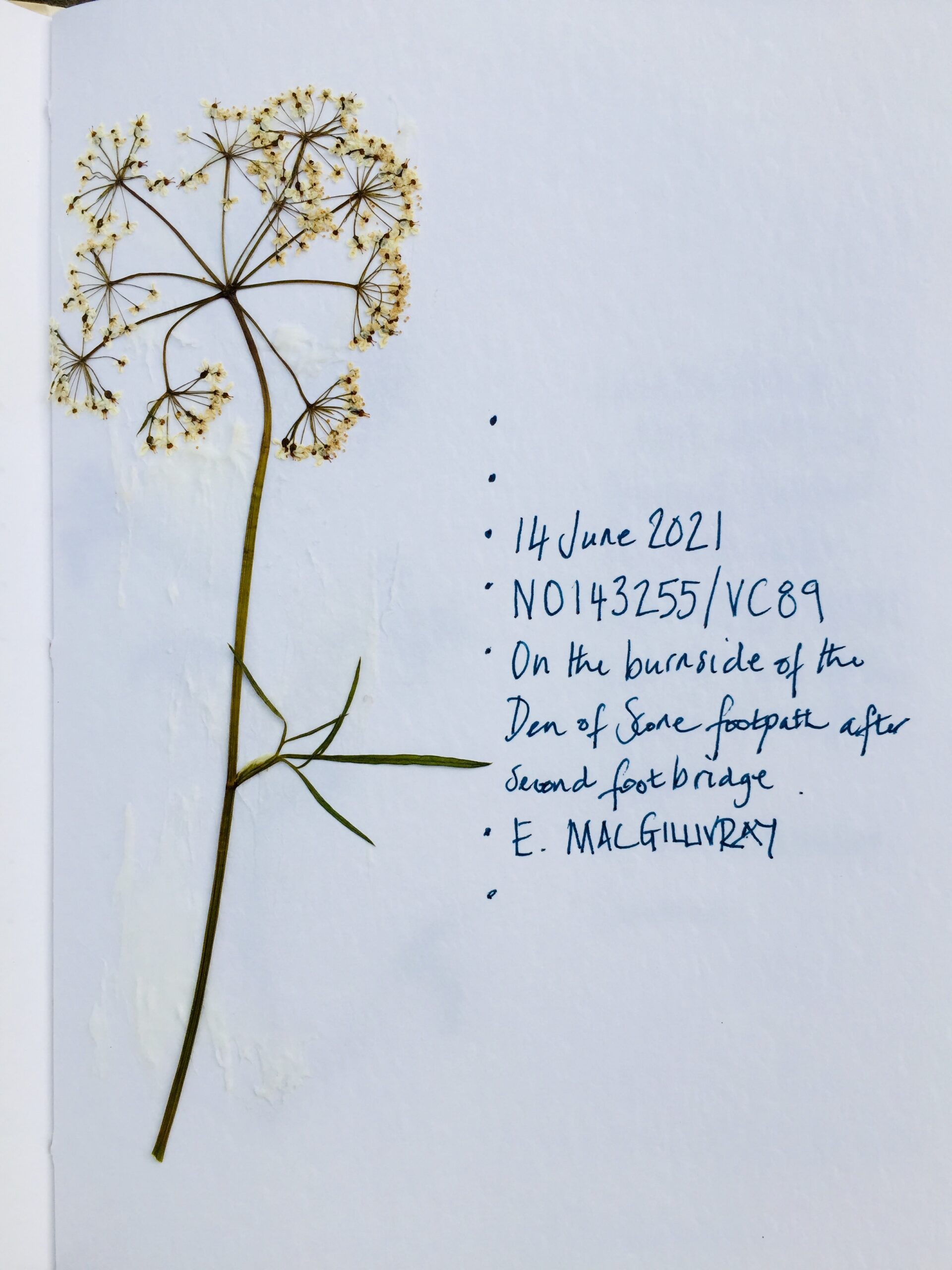

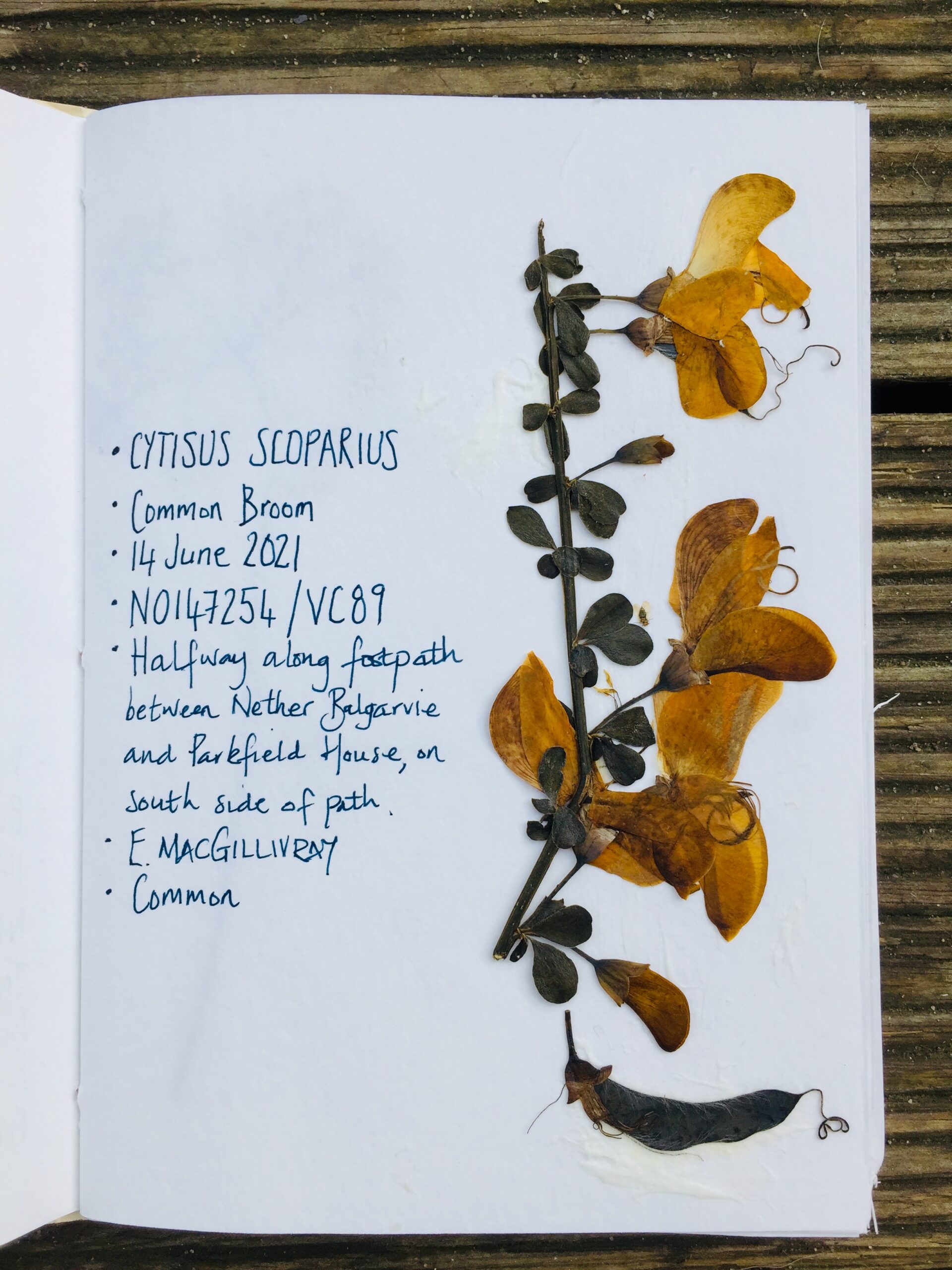

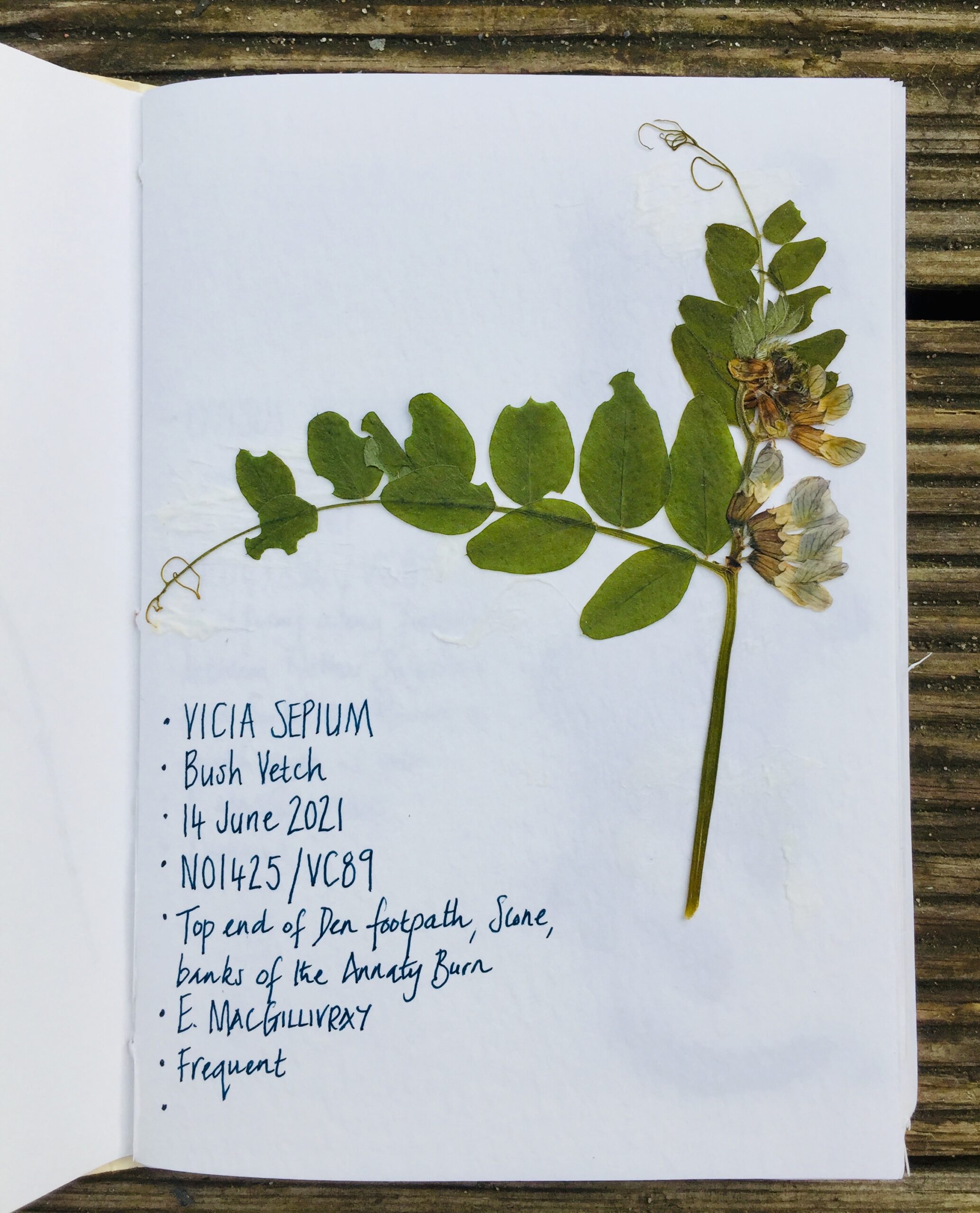

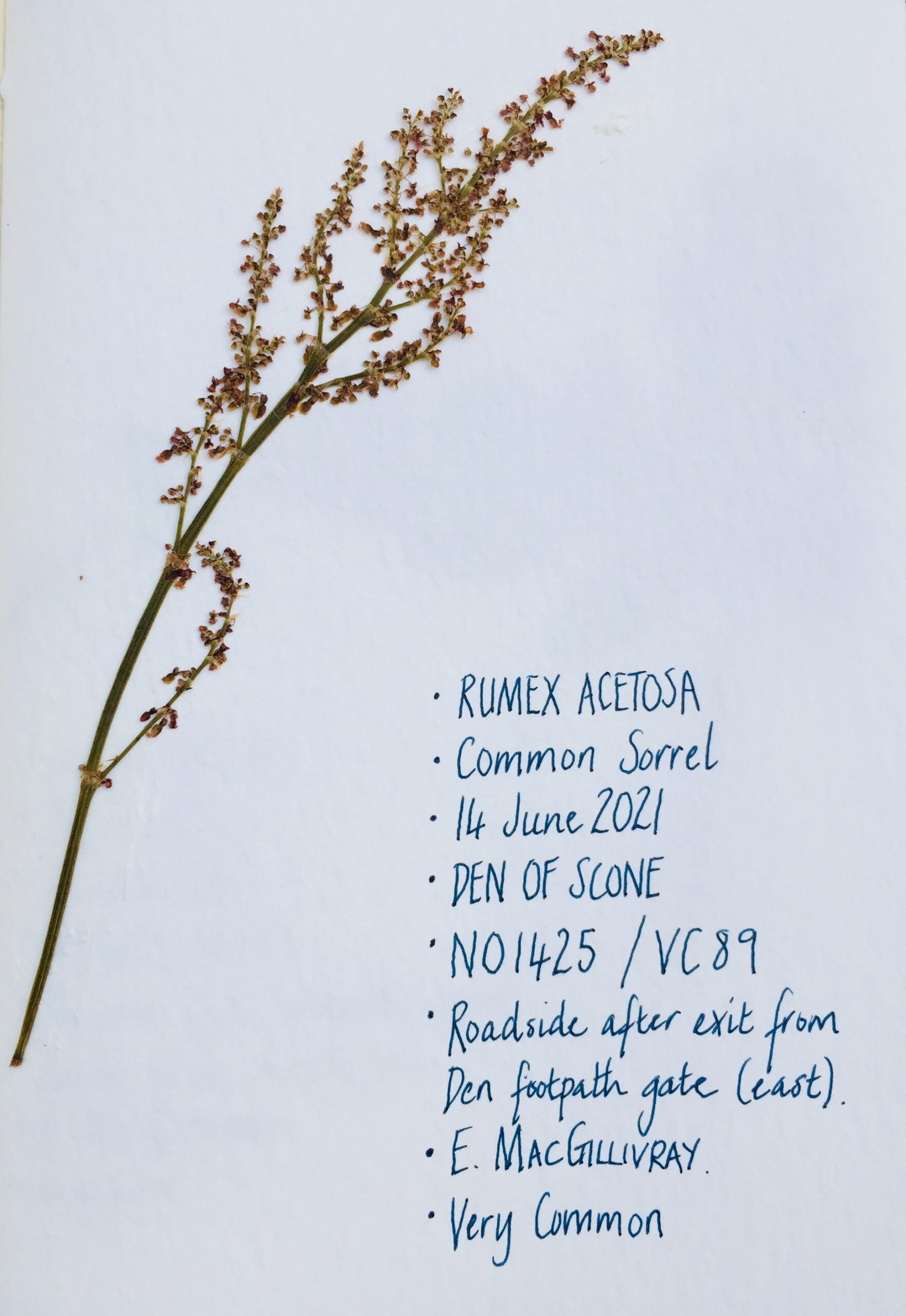

With this in mind and inspired by Joan Clark, earlier in 2021 I set out to collect some of my own herbarium specimens. I packed up my rucksack with the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland’s Guide to Collecting and Pressing Specimens, my phone (for the camera), a pair of scissors, a pack of coffee filters (in place of parchment paper), and Delia Smith’s Complete Illustrated Cookbook (the weightiest book in my library and my makeshift flower press).

Pressed plant specimen, ‘Bluebell’, collected by Elaine MacGillivray at the Den of Scone, June 2021.

I collected around 10 specimens from a local Perthshire woodland. Some of them I knew well, like the common broom, vetches, campion and bluebell; others left me scratching my head.

Pressed plant specimen, ‘Unidentified’, collected by Elaine MacGillivray at the Den of Scone, June 2021.

In attempting to identify my specimens, I found myself poring over Francis Buchanan White’s Flora of Perthshire (1898), the Perthshire Society for Natural Science’s Checklist of the Plants of Perthshire (1992), and an old copy of the Readers’ Digest Guide to Wildflowers of Britain (1996). I compared my specimens to photographs that I had of Joan Clark’s specimen books, and to images and descriptions on the webpages of the Scottish Wildlife Trust, Wildflower Finder, and the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. The result is that some of my metadata remains lacking until such a time as I can identify and name the plant, or until my newly acquired membership of the botany section of the Perthshire Society for Natural Science pays dividends!

Pressed plant specimen, ‘Common Broom’, collected by Elaine MacGillivray at Nether Balgarvie / Parkfield House, Scone, June 2021.

The creative process of collecting, pressing, identifying and documenting was completely absorbing. Through it I have learned to pay greater attention to my environment, gained a deeper understanding of my locality and the interdependence of people and plants. One of the many privileges of working so intimately with archival collections is that we are repeatedly offered a unique opportunity to develop knowledge and interest in a person, subject or era that otherwise may well have eluded us. In trying to see the world through the botanical wisdom of Joan Clark, the present-day natural world has opened up to me in a way I might never have imagined. I have an even greater respect for the knowledge, work, tenacity, dedication and patience that she and others must have brought to their botanical studies. I wonder what Joan Clark would have made of my amateur attempt to emulate her. I hope that she would be pleased that her legacy has inspired, and is able to continue to inspire, a new found passion to know, understand and protect plants and their environment.

-

-

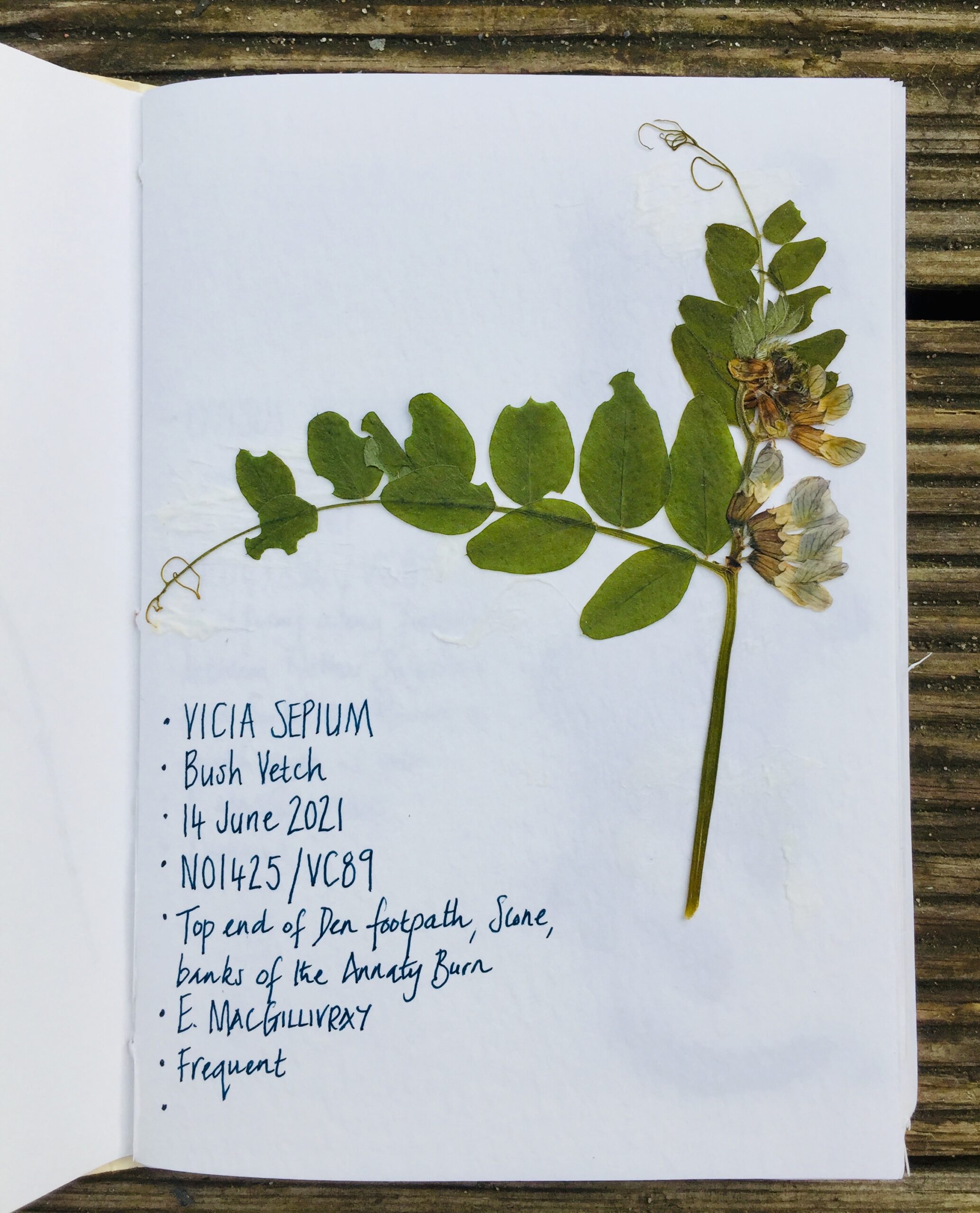

Pressed plant specimen, ‘Bush Vetch’, collected by Elaine MacGillivray at the Den of Scone, June 2021.

-

-

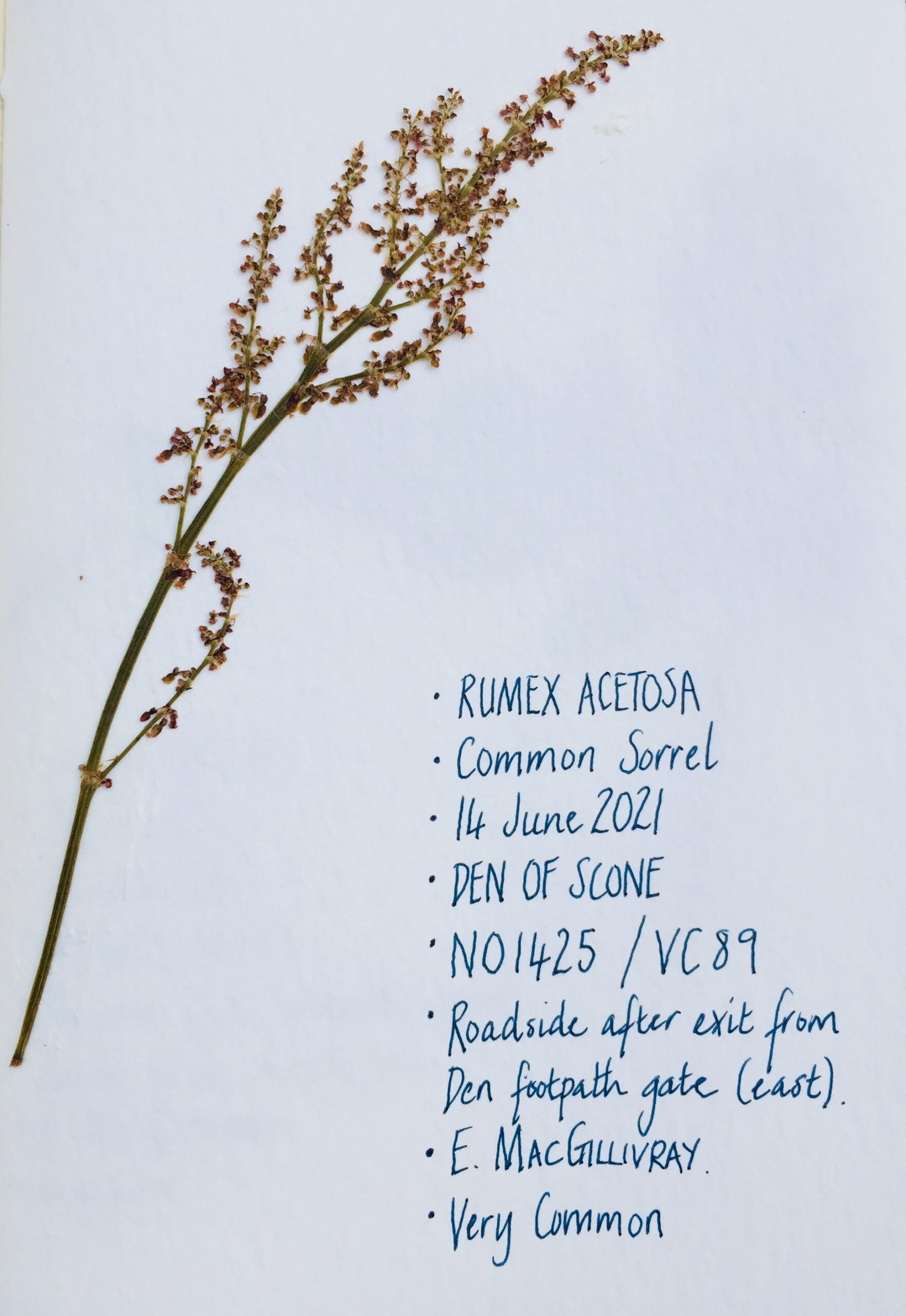

Pressed plant specimen, ‘Common Sorrel’, collected by Elaine MacGillivray at the Den of Scone, June 2021.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Louise Scollay, Caroline Milligan and Dr Ella Leith for their encouragement, prods, and proofreading.

Images are copyright, please do not reproduce.

Sources and further information:

Jermy, A.C., Obituary of Joan Wendoline Clark (1908-1999) in Watsonia, No. 23, (2000), pp.359-372 (http://archive.bsbi.org.uk/Wats23p359.pdf)

Murray, C.W., In Memorium – Joan W Clark (Rust) 1908-1999 in BSBI Scottish Newsletter, No. 22, (2000), pp. 12-13 (http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=2BC0FC507955B7D126E651E0C6CFE287?doi=10.1.1.659.2850&rep=rep1&type=pdf).

Elaine MacGillivray was the School of Scottish Studies Project Archivist, 2014-2016

Is there an ‘object’ related to the School of Scottish Studies that you would like to write about or respond to? It could be a recording, an image, a manuscript or something else!

We’d love to hear from you. Get in touch with us at scottish.studie.archives (at) ed.ac.uk