To mark the centenary of the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, we are publishing a blog by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement Team, which explores the archives of a Scottish survivor. The composer Sheena Tennant Kendall was resident in Japan from 1919 to 1924 and lived through the catastrophe, describing its impact in her diary and photographing the ensuing devastation. Continue reading

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Good Riddance to an ‘Intolerable’ Year: James Hogg Bids Farewell to 1831

To mark the 250th anniversary of the birth of James Hogg (1770-1835), we are featuring a peculiarly timely manuscript from Edinburgh University Library’s collections. Hogg’s poem ‘1831’ will strike a familiar chord with readers in 2020. It bids a hearty good riddance to a year plagued by a rampant epidemic, public unrest, conspiracy theories, and disruption to work and trade.

The poem’s refrain damns 1831 as the accursed year of ‘Burking, Bill, and Cholera’. The first major 19th-century outbreak of cholera reached Northern England in late summer 1831, probably via ships bringing imports from India. By the end of the year, it had entered Scotland, where it spread rapidly through the growing industrial towns, killing over 9,500 people. The disease also caused massive unemployment, particularly among weavers, as the demand for their wares plummeted. Quarantine regulations further prevented hawkers and travelling salesmen from travelling between towns. Economic deprivation led to ‘cholera riots’ in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Paisley. The target of the rioters’ fury was the medical profession which was suspected of Burking cholera patients. This term alluded to the body-snatching spree of Burke and Hare, crimes fresh in the public memory. It implied that doctors were systematically murdering cholera-sufferers to meet the demand for anatomic specimens.

Some protesters also claimed that the British government was deliberately spreading cholera in order to thin the numbers of the politically troublesome working classes. By ‘Bill’, Hogg means the Reform Bill of 1831, which envisaged a huge expansion of the (male) electorate. The rejection of the Bill by the House of Lords led to a nationwide outbreak of popular violence. Rioters set fire to Nottingham Castle (hence Hogg’s references to ‘flames’ and ‘fumes’) and seized control of Bristol for three days. Suspicion that cholera was being used to suppress the working classes blurred the boundaries between ‘Reform riots’ and ‘Cholera riots’.

Continue reading

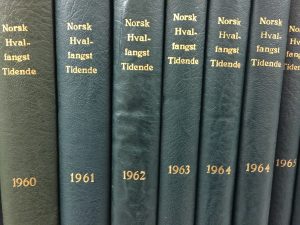

THE SALVESEN ARCHIVE CONTAINS THE NORWEGIAN WHALING GAZETTE, FROM 1917 TO 1968 – A WEALTH OF RESEARCH ON WHALES AND WHALING FROM THE DECADES PRIOR TO THE INTERNATIONAL WHALING COMMISSION (IWC) MORATORIUM, 1986

The Salvesen Archive is one of the larger collections in the care of the Centre for Research Collections (CRC). It is composed of manuscript and typescript material in the form of correspondence, diagrams, charts, accounting data, and photographs relating to some of the maritime and whaling activities of the long gone Christian Salvesen & Co. of Leith. It can be regarded as a ‘hybrid collection’ as well, containing printed pamphlets and journals, a small amount of books, and a few three-dimensional objects. Of particular interest to those keen to research the 20th century whaling industry is a reasonably long run of the periodical The Norwegian Whaling Gazette, or Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende.

The Salvesen Archive is one of the larger collections in the care of the Centre for Research Collections (CRC). It is composed of manuscript and typescript material in the form of correspondence, diagrams, charts, accounting data, and photographs relating to some of the maritime and whaling activities of the long gone Christian Salvesen & Co. of Leith. It can be regarded as a ‘hybrid collection’ as well, containing printed pamphlets and journals, a small amount of books, and a few three-dimensional objects. Of particular interest to those keen to research the 20th century whaling industry is a reasonably long run of the periodical The Norwegian Whaling Gazette, or Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende.

Bound copies of journal, ‘The Norwegian Whaling Gazette’ [Salvesen Archive]

Connections with the Norwegian Whaling Association became even closer on the appointment of Sigurd Risting (1870-1935) as editor in April 1922. Risting had been Secretary of the Norwegian Whaling Association. Formerly the headmaster of the local school, Risting had joined the editorial staff of the journal in June 1914.

On Risting’s death, Harald B. Paulsen (1898-1951) succeeded both as Secretary of the Whaling Association and as editor of the journal (Paulsen Peak in the Allardyce Range, South Georgia, was named after him). On his death, Einar Vangstein took over both jobs. Latterly, the journal had become a bimonthly title. In later years too, its articles appeared in both Norwegian and English.

By the late 1960s, all members of the International Association of Whaling Companies had ceased whaling and it was deemed no longer necessary for the continued publication of The Norwegian Whaling Gazette, and issue number 6, published November / December 1968, marked the end of its existence.

Articles in the journal were varied, scientific, and generally informative on many things cetacean, covering subjects such as: the determination of fat in whale meat extract; studies on the structure of baleen plates and their application to age determination; propellers for whaling ships made by KMW (Krauss-Maffei Wegmann, based in Munich); the marking of whales in New Zealand waters to measure resources; whales entangled in deep sea cables; the taxonomic position of the Pygmy Blue Whale; underwater sound from Sperm Whales; the cross-sectional anatomy of the dolphin; a new whaling station in Peru; and, the size of annual whale catches and annual seasonal oil production (indeed, throughout the life of the journal, the extent of whale catching and the size of the surviving whale was meticulously noted).

In addition, across many numbers of the journal during 1957 (Nos. 4-9), The Norwegian Whaling Gazette carried a historical narrative by the Norwegian Antarctic historian Hans Bogen, entitled Main events in the history of Antarctic exploration. Bogen also wrote a piece on Captain H. K. Salvesen for issue No. 9 of the journal in 1957.

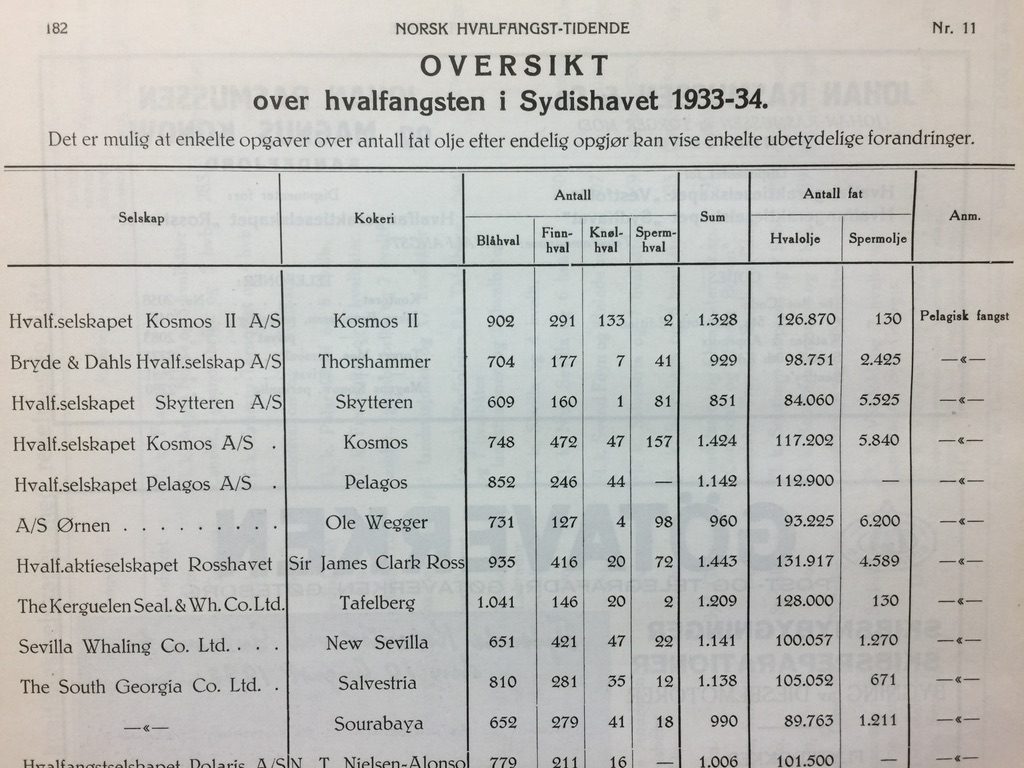

Article appearing in No.11 of ‘The Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, 1934, p.182, offering an overview of the whale catch in the Southern Ocean, 1933-34. The South Georgia Co. Ltd. was a subsidiary of Christian Salvesen Co. Ltd. and at that time the firm operated the whale factory ships ‘Salvestria’ and ‘Sourabaya’ as well as the ‘fast stasjon’ or land-based shore station at Leith Harbour, South Georgia. The other firm noted as having a shore station was Compañía Argentina de Pesca SA (the Argentine Fishing Co.) operating at Grytviken, South Georgia

The above illustrations together show a list appearing in No.11 of ‘The Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, 1934, p.182, describing the companies operating in the Southern Ocean during whale catch season 1933-1934. The columns show, from the left: name of company; type of ‘kokeri’, whether factory ship or shore station; number of whales caught, whether Blue Whale, Fin Whale, Humpback Whale (Knølhval), Sperm Whale; the combined total of all of these whale species; number of barrels of Whale Oil and Sperm Oil; and, notes on whether the production was during pelagic operations, or at a shore station

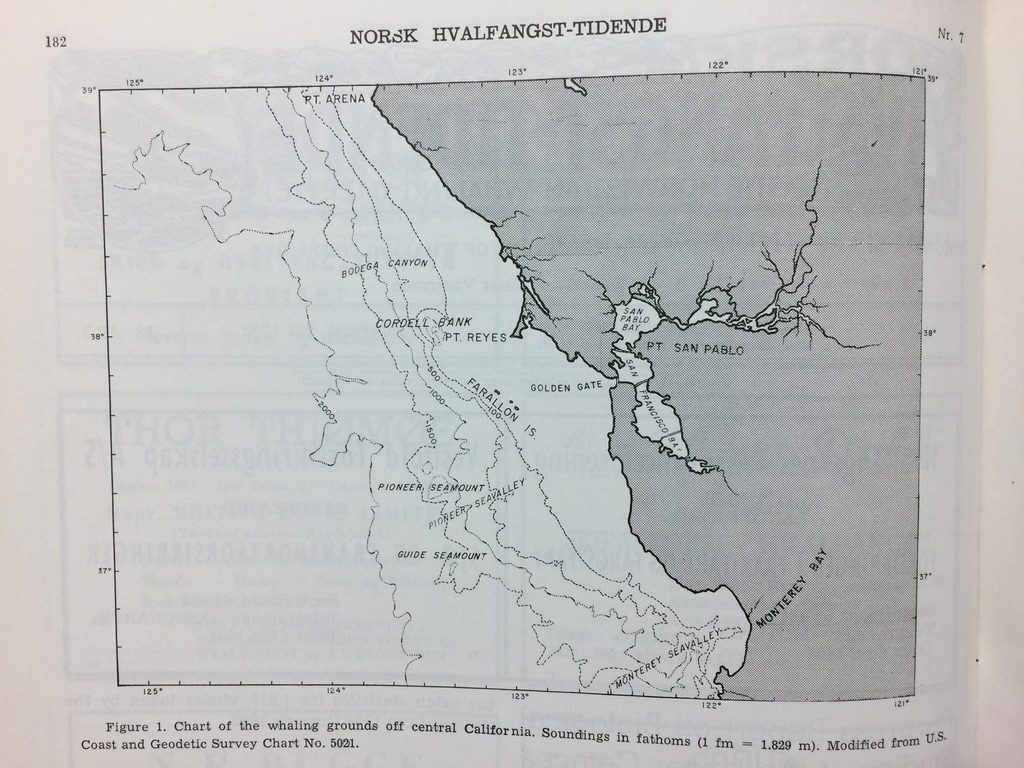

Chart of the whaling grounds off central California appearing in No.7 of The Norwegian Whaling Gazette, 1963, p.182. In the 21st century this maritime region can see 94% of migrating Pacific Grey Whales passing by, and Blue and Humpback Whales regularly feeding. Rather than facing slaughter, they are now the focus of a thriving tourist and whale watching industry. The main threats to nursing whales these days are ship propellers and Orca Whales

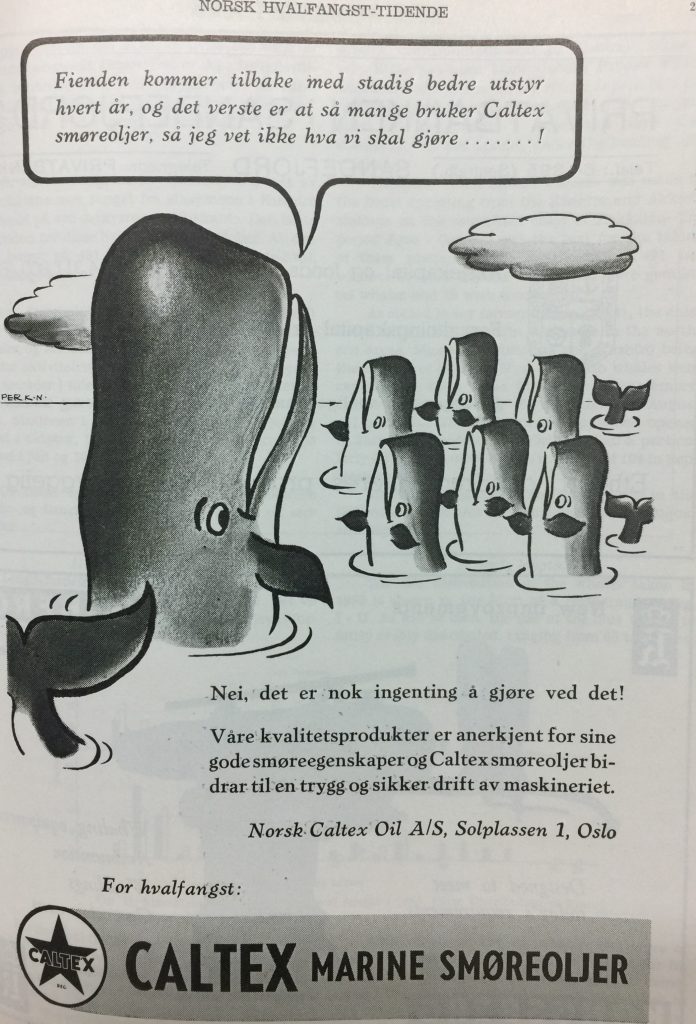

Advertising had provided the principal financial resource for the production of The Norwegian Whaling Gazette throughout its 57 years of life, with advertisements placed by firms involved in the supply to the whaling industry of goods and services as diverse as: industrial cookers and separators, ropes and line, whale cannons, explosives and gunpowder, marine oils and lubricants, and lowly milk powder.

Ad’ for unsweetened ‘Viking Melk’ (dried milk powder) produced by De Norske Melkefabriker, Oslo, Norway. The firm claimed that ‘Viking Melk’ had always been ‘in the field’. Produced in Norway, the powder possessed all the characteristics necessary for use in the whaling grounds, namely: durability in all conditions and applicability to all types of cooking on board [Ad’ from an issue of ‘The Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, Salvesen Archive]

Ad’ for Caltex Marine Oils, placed by Norsk Caltex Oil A/S, Oslo, Norway. Caltex oils, the company claimed, were quality products recognized for their good lubricating properties, and Caltex lubricating oil contributed to a safe and secure operation of machinery. The ad’ was illustrated with a pod of whales. with the pod leader lamenting that the ‘enemy keeps coming with better equipment every year, the worst of it being that so many of them are using Caltex lubricating oil that I don’t know what we are going to do!’ [Ad’ from an issue of ‘The Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, Salvesen Archive]

Ad’ placed by the Greenock Dockyard Company, Greenock, Scotland, a yard which built many types of vessel and performed repairs to them too. It was incorporated as Greenock Dockyard Co. Ltd. in 1920, and was earlier known as the Greenock & Grangemouth Dockyard Co., and before that had been owned by Russell & Co. of Greenock, and prior to that J. E. Scott of Greenock [Ad’ from an issue of ‘The Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, Salvesen Archive]

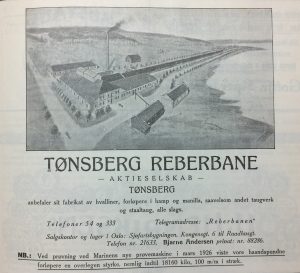

Ad’ for the former Tønsberg Reberbane AS, in Tnsberg, Vestfold, Norway. Tonsberg ropeworks….:

Graeme D. Eddie, Honorary Fellow, Centre for Research Collections, Edinburgh University Library… engaging with the Salvesen Archive of maritime trading and whaling

References:

Vangstein, Einar. ‘Editorial – The Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende, Vol.57. No.6, Nov/Dec.1968, p.117

If you have enjoyed reading this post, check out previous ones about the Salvesen Archive, or using Salvesen Archive content, which have been posted by units across CRC since 2014:

A narrative on the whaling industry: as told through a whale catch log-book and other items in the Salvesen Archive October 2019

Salvesen Archive – 50 years at Edinburgh University Library – 1969-2019 May 2019

Cinema at the whaling stations, South Georgia August 2016

Exploring the explorer – Traces of Ernest Shackleton in our collections May 2016

Maritime difficulties during the First World War – Christian Salvesen & Co. October 2015

Talk on the Salvesen Archive to members of the South Georgia Association November 2015

‘Empire Kingsley’ – 70th anniversary of sinking on 23 March 1945 March 2015

Pipe bombs, hurt sternframes, peas, penguins, stoways and cookery books: the Salvesen Archive July 2014

Whale hunting: New documentary for broadcast on BBC Four June 2014

Penguins and social life May 2014

A narrative on the whaling industry: as told through a whale catch log-book and other items in the Salvesen Archive

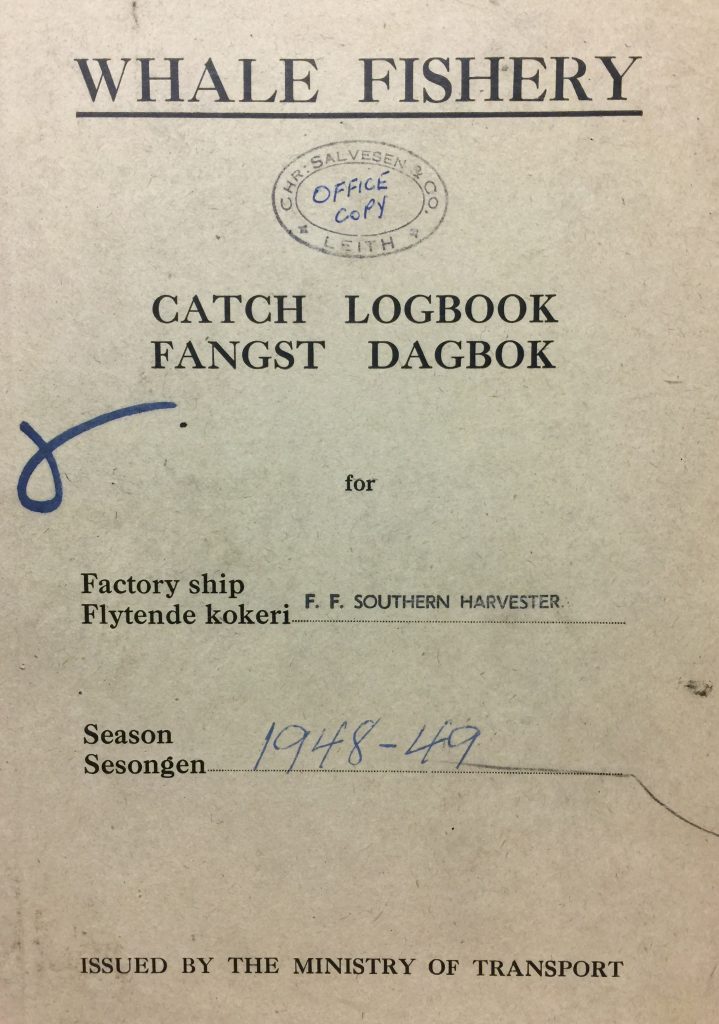

WHALING AS TOLD THROUGH A CATCH LOG-BOOK – THE FANGST DAGBOK of SOUTHERN HARVESTER, SEASON 1948-49, A FLOATING FACTORY OPERATED BY THE SOUTH GEORGIA CO., A SUBSIDIARY OF CHRISTIAN SALVESEN OF LEITH

Catch log-book of the ‘Southern Harvester’ – a stern-slip whaling factory-ship – for season 1948-49. Many of the crew, particularly the officers, were Norwegians and a vessel’s catch log-book, or ‘fangst dagbok’ was bilingual in response to this

A vessel’s log-book provides a record of the most important daily events in its management and operation. Log-books have long been vital to navigation, and most national shipping authorities and admiralties require these to be maintained should radio, radar and global positioning systems (gps) fail. Log-books and their data can be of great importance in any legal case involving maritime accidents or disputes.

Cover of the ‘Southern Harvester’ catch log-book issued by the UK Ministry of Transport and relevant to whaling season 1948-49 [Salvesen Archive]

However, a log-book can tell us so much more than weather, navigational and catch data, as the whale catch log-book of the stern-slip factory-ship Southern Harvester illustrates.

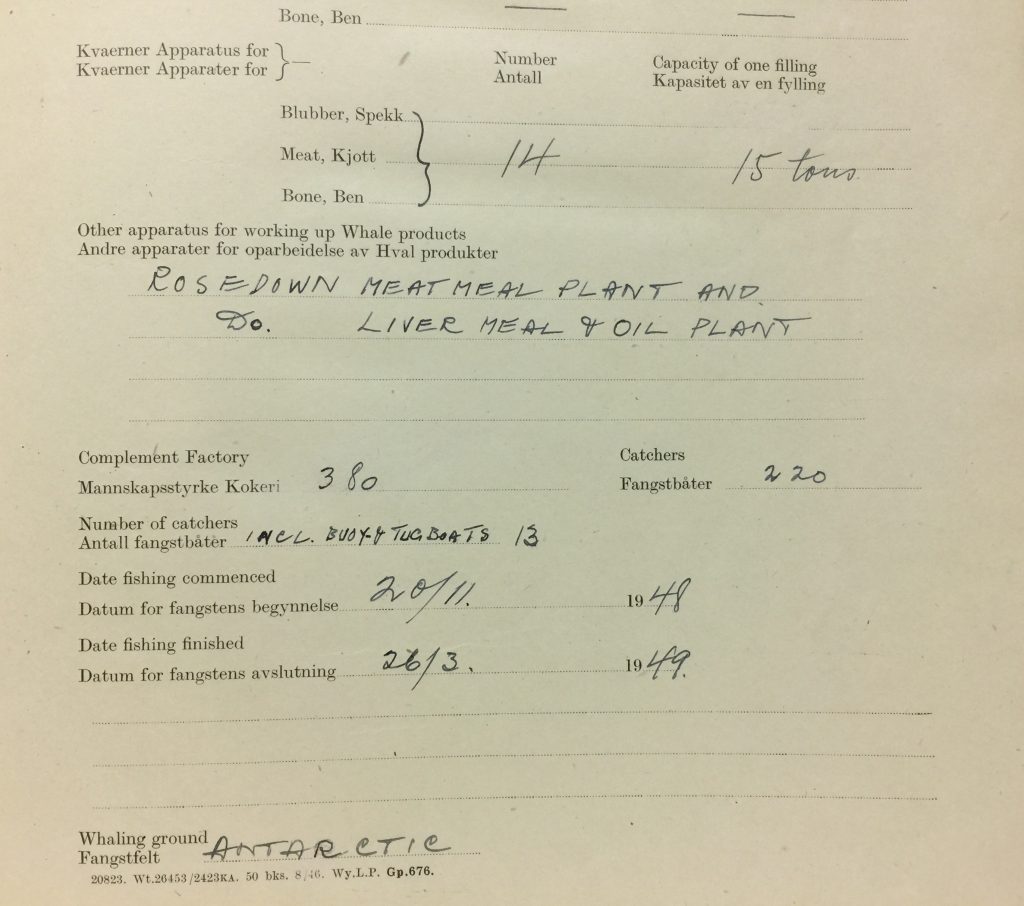

The opening page of the 1948-49 catch log-book notes the basic statistics of the floating factory. At the start of the whaling season late-1948 it had a gross tonnage of just over 15,087 tons, and a net tonnage of over 8,092 tons (gross tonnage being the volume of all enclosed spaces of the ship, and net tonnage the volume of all cargo spaces of the ship). The tonnages might vary from season to season depending on whether or not maintenance of the vessel and any refitting or conversions had affected its configuration.

Basic statistics and technical data relating to the ‘Southern Harvester’ captained by Konrad Granøe, which included the information that the vessel was fitted out with 14 whale oil boilers and 2 Hartmann’s Apparatus [Title page of the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

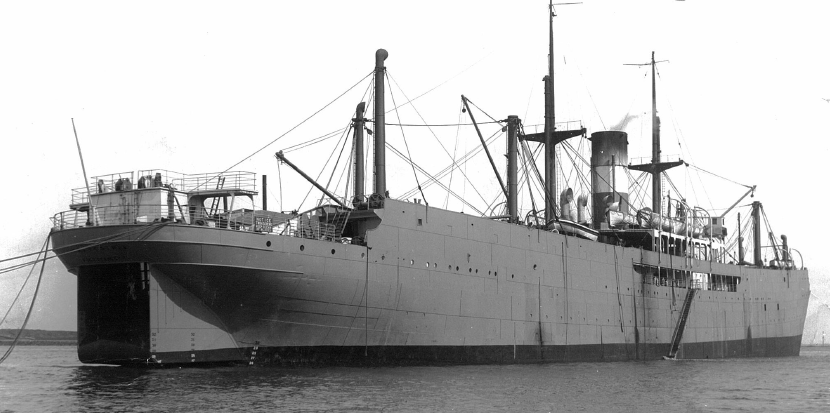

The stern-slip whale factory ship ‘Southern Harvester’. The stern-slipway enabled whales to be hauled directly onto the flensing deck of the vessel where they could be cut down and then processed – ‘worked up’ – below decks in a battery of cookers and boilers [Photographic collection, Salvesen Archive]

Painting of the ‘Southern Venturer’ – sister ship of the ‘Southern Harvester’ – showing the stern-slipway for hauling whales up onto the flensing deck. The painting was the work of George McVey, 1956, and was featured on the cover of the book ‘Salvesen of Leith’, by Wray Vamplew, Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh and London, 1975

The log-book shows that the 1948-49 season began on 20 November 1948, and ended on 26 March 1949, and that the floating factory Manager (its Captain) had been Konrad Granøe (1889-1961). Granøe was a Salvesen (South Georgia Co.) veteran, serving as Mate aboard the Saragossa during the seasons from 1924 to 1928, attending Masters’ training 1928-29, serving as Manager of Saragossa, New Sevilla, and Salvestria between 1929 and 1936, serving throughout the Second World War, and then serving as Manager of the Southern Harvester from catch season 1947 through to the end of the 1950 season.

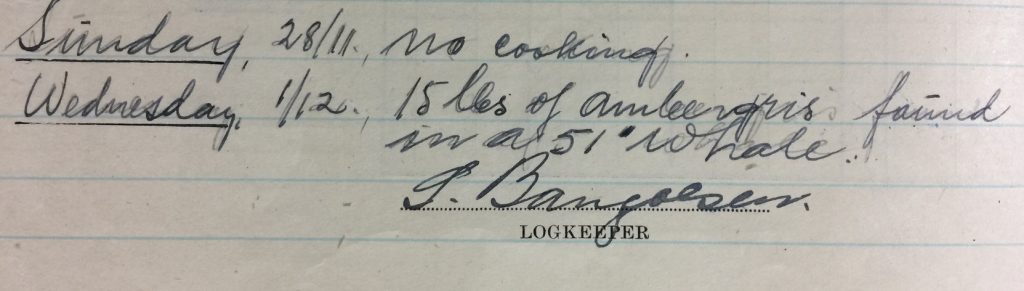

The log-book had been written up by another Salvesen veteran, Sigurd Jørgen Bang-Olsen (born in 1902), who had served aboard both the Southern Harvester and Southern Venturer during various catch seasons from 1945 until 1963, and whose career with Salvesen began in Leith Harbour, South Georgia, in 1926. He experienced shore-station work at Leith harbour until 1930 and again during the 1940s (also at the offices of Tønsberg Hvalfangeri, South Georgia) and from 1950 until 1957.

Completed in 1913, the Salvesen vessel ‘Salvestria’ had been captained by Konrad Granøe in the 1930s, and it was lost August 1940 after it struck a mine in the Forth estuary off Inchkeith during the last leg of a voyage from Aruba in the Caribbean to Grangemouth. Sigurd Jørgen Bang-Olsen had also served on ‘Salvestria’ [Photographic collection, Salvesen Archive]

Technical data relating to the ‘Southern Harvester’ indicating that the vessel was kitted out with a Rosedown Meatmeal Plant and Liver Meal and Oil Plant [Title page of the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

Hartmann equipment for whale oil production shown in an advertisement stating that there were 4 such apparatus aboard the ‘Southern Venturer’, which was the sister ship of ‘Southern Harvester’ [From a copy of ‘Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende’ / ‘Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, Salvesen Archive]

Kvaerner Apparatus on railway wagons leaving the Kvaerner Works in Oslo, Norway [Advertisement from a copy of ‘Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende’ / ‘Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, Salvesen Archive]

Processing of whales – ‘working up whales’ – aboard an early floating factory. Processing was conducted below decks aboard the ‘modern’ vessels constructed during the 1940s [Photograph among material gifted by Sir Gerald Elliot in 2012, Salvesen Archive]

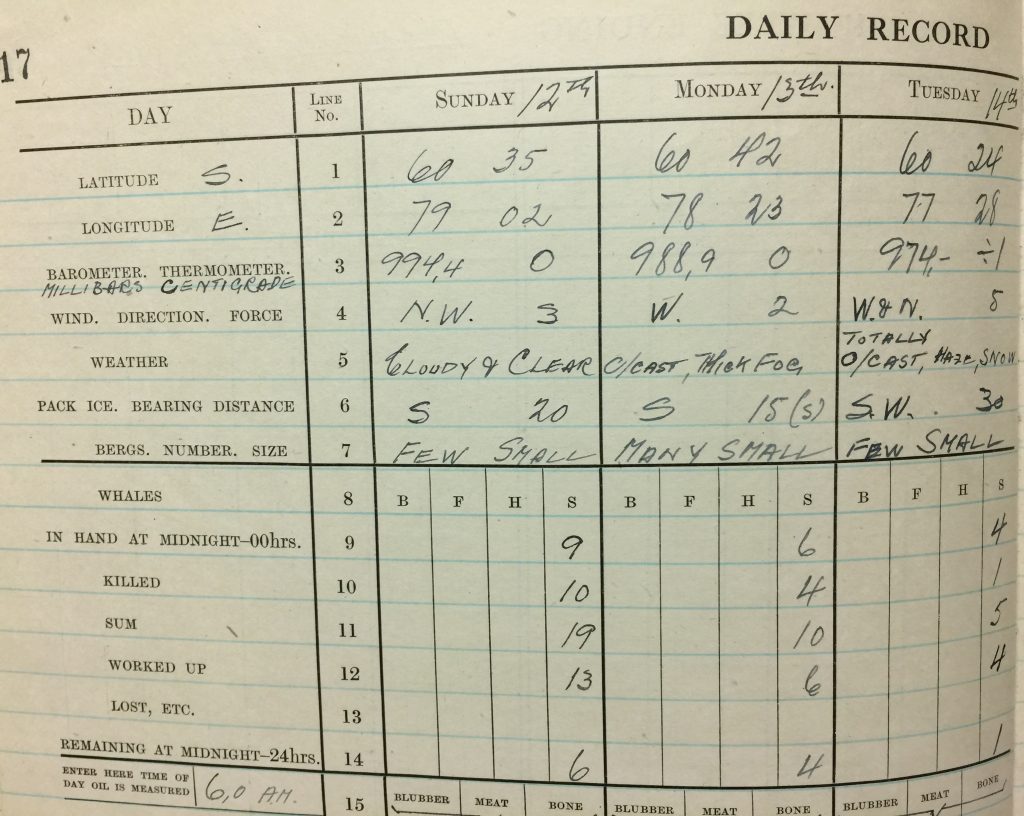

Page of the ‘Southern Harvester’ floating factory whaling log-book showing the vessel’s position on 12 December 1948. Latitude 60° 35′ South and longitude 79°02′ East was a location half-way between the Davis Station, Antarctica, and Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI), in the Southern Indian Ocean [In the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

In addition to the 9 ‘in hand’ at the start of the period, another 10 Sperm Whales had been killed over the course of the day (making 19 in total), and over the day 13 Sperm Whales of the total had been processed.

The above page of the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book informs us that ‘baleen whaling commenced 15 December 1948’. Sperm Whales (abbreviated as ‘S’ in the data) are of course toothed whales, Odontoceti. From 15 December, the log-book showed the catching of Blue Whales (‘B’) and Fin Whales (‘F’) which, together with Sei, Humpback, Bowhead, Gray, Minke, and others, are all baleen whales, Mysticeti [Page in the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

The catch log-book, kept up-to-date by the log-keeper, Sigurd Jørgen Bang-Olsen, has noted that on 12 December 1948 a 6.8 kilogram mass of ambergris had been found in a whale (the ambergris noted as being 15 pounds imperial weight). Ambergris is formed from a secretion of the bile duct in the intestines of the sperm whale, and would normally be passed in fecal matter. Ambergris acquires a sweet, earthy scent as it ages and so had been very highly valued by perfumers as a fixative allowing the scent to last much longer [Page in the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

Signature of Konrad Granøe (1889-1961), Manager of the ‘Southern Harvester’ [Page in the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

Graeme D. Eddie, Honorary Fellow, CRC, engaging with the Salvesen Archive of maritime trading and whaling

References:

In the creation of this post the following resources were used: (1) Ogden, Lesley Evans. ‘New data from old treasures: Whaling logbooks’, BioScience, Vol.66, Issue 7, 1 July 20-16, p. 620; (2) Wilkinson, Clive. ‘Ice and Meteorological Data in the Christian Salvesen Archive, University of Edinburgh’, Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia Norwich UK & Faculty of Natural Resources, Catholic University of Valparaiso, Chile, 2013; (3) RECLAIM project, https://icoads.noaa.gov/reclaim/ [accessed 25 September 2019]; and (4) ‘The 19th-century whaling logbooks that could help scientists’, The Guardian, Thursday 17 December 2015.

If you have enjoyed reading this post, check out previous ones about the Salvesen Archive, or using Salvesen Archive content, which have been posted by units across CRC since 2014:

Salvesen Archive – 50 years at Edinburgh University Library – 1969-2019 May 2019

Cinema at the whaling stations, South Georgia August 2016

Exploring the explorer – Traces of Ernest Shackleton in our collections May 2016

Maritime difficulties during the First World War – Christian Salvesen & Co. October 2015

Talk on the Salvesen Archive to members of the South Georgia Association November 2015

‘Empire Kingsley’ – 70th anniversary of sinking on 23 March 1945 March 2015

Pipe bombs, hurt sternframes, peas, penguins, stoways and cookery books: the Salvesen Archive July 2014

Whale hunting: New documentary for broadcast on BBC Four June 2014

Penguins and social life May 2014

‘Not a Varsity Bird’: William Soutar’s Student Years

100 years ago this week, one of Scotland’s best-loved poets became a student of Edinburgh University. On 13 October 1919, the 21-year-old William Soutar added his name to the university’s Matriculation Album as a first-year student of English Literature.

Extract from Matriculation Album (EUA IN1/ADS/STA/2)

Like many young men of his generation, Soutar’s student years were delayed by war service. On leaving school in 1916, he joined the Royal Navy and spent two years with the North Atlantic Fleet. By the time he was demobbed in November 1918, he was already suffering from as yet undiagnosed ankylosing spondylitis, a rare and exceptionally crippling form of arthritis, which would lead to almost complete paralysis by 1930 and contribute to Soutar’s early death in 1943. Following a month in hospital, Soutar recovered sufficiently to come to Edinburgh in spring 1919 with the initial intention of studying medicine. Soutar appears to have attended classes without matriculating but found the anatomical specimens so ‘gruesome’ that he abandoned medicine after a fortnight, resolving to switch to honours English after the summer vacation. He found time, however, to contribute a poem to the 21 May edition of The Student, ‘Orpheus’, a lushly Romantic piece heavy with echoes of Keats and Shelley.

Extract from ‘The Student’, 21 May 1919

Soutar did not enjoy a distinguished university career. The first two years of his honours English course passed smoothly enough. He enjoyed Professor Herbert Grierson’s lectures on the English classics, particularly appreciating Chaucer, Wordsworth, and Donne. He read widely, ranging far beyond the curriculum, and as his taste developed, was moved to destroy most of his own teenage production. He wrote prolifically, devoting three months of his first academic years to a long poem ‘Hestia, or the Spirit of Peace’ in a vain effort to win the university’s Poetry Prize. Although he continued to suffer from stiffness of the joints, he was still sufficiently vigorous to sit as a model for his friend James Finlayson’s painting of the warrior-hero Beowulf.

At the beginning of his third year, Soutar was dismayed to discover how prominent a role Anglo-Saxon would play in the Junior Honours curriculum. Finding linguistic studies ‘musty stuff’, he contributed a letter-article to The Student of 21 November, arguing that Anglo-Saxon should be optional. Although it offered a ‘large field to the specialist’, Anglo-Saxon contributed little to the average student’s knowledge and appreciation of the literature of his country’. It occupied far too many of the undergraduate’s studying hours which ‘ought to be given to the far more significant study of the great masters of English literature’.

Extract from ‘The Student’, 21 November 1921

Soutar reluctantly attended third-year Anglo-Saxon lectures but stepped up his campaign against the subject in his Senior Honours year. He was granted an interview with Professor Grierson on 23 October 1922, but failed to convert him to his cause. At his parents’ insistence, Soutar dropped his public opposition to Anglo-Saxon, but ceased attending classes, having been assured that he would still be permitted to sit his honours exam. Although Soutar increasingly devoted his evening hours to cinema-going and card-playing, his final year was nonetheless of vital importance for his development as a poet. His first volume, Gleanings of an Undergraduate, was published in his native Perth on 9 February 1923. Meanwhile, influenced by Hugh MacDiarmid, whom he had met during the 1922 summer vacation, he extended his knowledge of Scots verse beyond Burns to the medieval makars. His work began to appear in the MacDiarmid-edited journals Northern Numbers and The Scottish Chapbook, which spearheaded what came to be known as Scottish Literary Renaissance.

Title page of William Soutar’s first published volume, inscribed by the author (probably to art critic John Tonge) (JA 3537)

At the end of the spring term of 1923, Soutar fared disastrously in a preliminary exam on Shakespeare. When Professor Grierson subsequently remarked in a lecture that an honours course was not really for ‘Minor Poets, Geniuses or Journalists’, Soutar suspected that he was the target. Soutar’s final examinations were held on 15 and 19 June, and at the end of the month he learned that he had ‘scraped through’ with a third-class degree. Looking back, he suspected that aversion to Anglo-Saxon was not the sole reason for his low marks. In his exclusive passion for poetry, he had refused to read any of prescribed. It is also true that his medical condition, provisionally diagnosed as ‘rheumatics’, had worsened during his final year of study and may well have affected his academic performance. Soutar remained philosophical, reflecting: ‘I’m afraid I’m not a ‘Varsity bird’—one is apt to get cobwebs on one’s wings’.

Soutar graduated from Edinburgh University on 12 July 1923. Over the following months, his illness worsened, frustrating his hopes of becoming a journalist for The Scotsman. He began teacher training in October 1924 but had to return to Perth to begin treatment for his finally diagnosed ankylosing spondylitis. From then on, he was confined to his parents’ house, from which he would published a stream of slim volumes containing some of the finest Scots verse of the 20th-century. The best-known perhaps are the ‘bairn-rhymes’, or Scots children’s verse, collected in Seeds in the Wind. Soutar famously remarked that ‘if the Doric is to come back alive, it will come first on a cock-horse’.

For Edinburgh University’s collection of William Soutar manuscripts, see: Papers of Willam Soutar (Coll-796)

All quotations from: Alexander Scott, Still life: William Soutar, 1898-1943 (London: Chambers, 1958)

Paul Barnaby

Acquisition and Literary Collections Curator

‘This Single Song of Two’: Centenary of the Marriage of Edwin and Willa Muir

7 June 2019 marks the centenary of the marriage of Edwin and Willa Muir, one of Scottish literature’s great creative partnerships. Acclaimed in their own right as poet and novelist respectively, they worked together as a translating team to bring the novels and stories of Franz Kafka to an English-speaking audience.

Edinburgh University holds a number of remarkable documents, bearing witness to their long and exceptionally close union.

Continue reading

Salvesen Archive – 50 years at Edinburgh University Library – 1969-2019

50th ANNIVERSARY OF THE ARRIVAL OF THE CHRISTIAN SALVESEN & CO. ARCHIVE AT CRC – MARITIME TRADING AND WHALING MATERIAL

50 years ago in May 1969 former colleagues of the Centre for Research Collections had been busy collecting a large maritime trading and whaling archive from the offices of Christian Salvesen & Co. in Leith. The collection of company records was deposited on ‘permanent loan’, and would be joined by a second tranche in 1990, and a third in 2008. A gift of the entire archive to Edinburgh University Library was negotiated and signed in May 2012. That year, a small additional collection of material relating to the firm and its activities was received from Sir Gerald Elliot (1923-2018), a great-grandson of Christian Salvesen (1827-1911), the founder of the company.

Christian Salvesen and his wife Amelie, with their family, and photographed on holiday in Norway, in about 1860. The children may be (from left to right) Johan Thomas (b. 1854?), Edward Theodore (b.1857), and Frederick (b. 1855).

From Mandal, Norway, Salve Christian Fredrik Salvesen, son of a Norwegian merchant ship owner, first arrived in Scotland in the 1840s working at the Grangemouth shipbroking business owned by his brother, Johann Theodor Salvesen (1820-1865). Later on, after gaining experience on the continent, at Szczecin (then Stettin), he returned to Scotland and joined his brother again at Salvesen & Turnbull, now in Leith. On Johann’s retirement, the name changed to Turnbull, Salvesen & Co. The firm imported grain and timber, exported coal and iron, and also handled cargoes of salt and Norwegian herring. The carrying of migrants and gold prospectors to Australia was also an important trade.

Letter addressed to Christian Salvesen at the offices of Messrs Turnbull and Salvesen & Co., Leith, May 1861.

Following his brother’s early death in 1865, and after arguments with Turnbull, Salvesen went into business on his own, and his new firm, Chr. Salvesen & Co. began life on Bernard Street, Leith, in 1872. This change coincided with the advent of the steamship, and the expansion of maritime commerce with German and Baltic ports. In the 1880s, Salvesen was joined in the business by three of his sons.

For the Salvesen whaling enterprise in the South Atlantic, a subsidiary company was formed – the South Georgia Company of Leith (1909-1966), based at Leith Harbour, Stromness Bay, South Georgia.

By 1911, the year of Salvesen’s death, the firm’s vessels were trading with ports on the Baltic, in Norway and Sweden, and were servicing whaling stations in the Arctic, Iceland and the Faroe Islands. Cargo lines were also opened up between Leith, Malta, and Alexandria, and then into the Black Sea.

The Salvesen Archive contains ledgers and cash and account books in various forms, both from the firm Christian Salvesen & Co., and the important subsidiary, the South Georgia Co.

During that first decade of the 20th century, the shipping industry was in a depressed state and, globally, shipping companies made heavy losses. While the Salvesen fleet fared no better, the company’s whaling interests – now expanding as far as the Falkland Islands and South Georgia – helped it to show occasional profit. The Salvesen whaling enterprise in the waters of the South Atlantic was operated by a subsidiary company, the South Georgia Company of Leith (1909-1966), based at Leith Harbour, Stromness Bay, South Georgia.

Whale on the ‘slip’ prior to be being ‘worked’, South Georgia. From a large photograph collection in the Salvesen Archive.

Into the 20th century, whaling began to dominate Salvesen business and the firm became an industry leader just at the time when food oils and other products from the Antarctic were considered a boundless resource.

Conservation of species… far from the concern of our own time… Report on whale stock and conservation in The Times, 9 September 1918, from a correspondent in Oslo. However, the concern about conservation at that time was not so much about the various whale species themselves, but rather more about continuing access to whale oils. Conservation of whale oils, rather than conservation of whales. From a collection of newspaper cuttings albums in the Salvesen Archive.

A third Salvesen generation entered the business in the troubled economic period of the inter-war years. The firm managed to ride out these troubled times, and whaling was expanded and modernised. As stocks began to diminish however, the firm of Salvesen – whalers for nearly 70 years – was prominent in urging conservation. In 1963, they gave up whaling.

Distinctive funnel colours of the Chr. Salvesen & Co. shipping line shaded-in on the plans for the whale catchers ‘Southern Lily’ and ‘Southern Laurel’. From a collection of plans in the Salvesen Archive.

By the 1960s and 1970s, a fourth generation was still playing an important role in the firm, and over that period the company had begun to diversify its interests: home construction; canning, and cold-storage facilities; food processing; frozen and chilled food logistics; generator rental; off-shore oil support; and, road transport logistics.One of Salvesen’s acquisitions was the Buttercup Dairy cold storage business, taken over in 1964… though the company was unable to save the well-known and popular Buttercup Dairy stores.

Day Books of the Aberdeen-based Glen Line, a shipping firm owned by John Cook and Son which had been an acquired by Christian Salvesen & Co. in 1928.

In 1985, Salvesen went public on the London Stock Exchange – Christian Salvesen PLC. In 1990 the firm left shipping, and in 1997 it moved to Northampton, England. In October 2007, the Christian Salvesen board recommended a takeover of the firm by Norbert Dentressangle, the large French-based European logistics firm (the unmissable red trucks of Groupe Norbert Dentressangle are almost on a par with Eddie Stobart among the lorry-spotting community!).

The Salvesen Archive includes many years of the ‘Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, or’ Norsk Hvalfangst Tidende’, which is rich in articles concerning the whaling industry (in Norwegian and English), and rich in contemporary whaling industry advertisements.

It was with Christian Salvesen Investments Ltd., a Groupe Norbert Dentressangle subsidiary, that the Centre for Research Collections would finally agree acquisition of the Salvesen Archive in 2012, so ending much involved contact and conversation between CRC staff and the firm in Northampton over access to the deposited collection.

Advertisement for BP bunker fuel placed in the ‘Norwegian Whaling Gazette’.

Taking up just short of 70 metres of storage space, the archive is composed of a wide mix of material representing the firm’s early shipping interests, its whaling interests, and the firm’s later diversification. The archive includes: office ledgers; cash, accounts and invoice books; letter and day books; order and stock books; whale catch records; log books; correspondence; newspaper cuttings; photographs; and, copies of the ‘Norwegian Whaling Gazette’ and the company magazine of latter years ‘Salvesen News’.

Advertisement placed in the ‘Norwegian Whaling Gazette’ by the Tønsberg ‘ropewalk’ (or reperbane), a covered pathway, where long strands of material are laid before being twisted into rope.

When the first tranche of the archive arrived at the Library in 1969, Christian Salvesen & Co. had been preparing to make a move from their offices at 29-33 Bernard Street, Leith, to larger and recently constructed premises at Citadel House, East Fettes Avenue, in Edinburgh. Doubtless the impending move had spurred the firm into disposing of unneeded company records, and the National Register of Archives for Scotland (NRAS) had surveyed and drawn up a list of material in July 1968.

Whales being ‘worked’ on a whale factory ship. From a photograph in the Salvesen Archive photograph collection.

The NRAS list shows that the material now in the care of CRC had been located at several places: Inveralmond House, Cramond, the home of Captain Harold Keith Salvesen (1897-1970), grandson of Christian Salvesen; Attic No.1 at the firm’s offices, 29 Bernard Street, Leith; Metal cupboards at the top of the stairs at the same location; Captain H. K. Salvesen’s room in the offices at the time of the survey; and, the Operations Store Room, at the Bernard Street offices (it is worthwhile noting here too that some material in the second tranche, 1990, had been drawn from not only the headquarters in Edinburgh, but also from the abandoned whaling stations on South Georgia).

The interior of the cinema at Leith Harbour. Many of the films (in Norwegian and English) were brought out to South Georgia from Norway and the UK.

In 1968, the Library had moved into its new premises on George Square in closer proximity to the academic community and departmental offices, and from an exchange of correspondence between the Company and the Library, and between the Library and Professor Samuel Berrick Saul (1924-2016), Economic History, it can be speculated that Professor Saul may have been a prime mover in having the Salvesen Archive brought to the Library. As an economic historian, he may have been helping us to build up a business archive. Professor Saul had facilitated the commissioning of Mr Wray Vamplew, a postgraduate Economic History student, to write a history of the Company.

Painting of a whale factory ship, the ‘Southern Venturer’, by George McVey, which illustrates the cover of Wray Vamplew’s book, ‘Salvesen of Leith’.

The book, entitled Salvesen of Leith, was eventually published by the Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh and London, 1975.

Copies of the Salvesen in-house magazine. From a run of the magazine in the Salvesen Archive.

Graeme D. Eddie, Honorary Fellow, CRC… Engaging with the Salvesen Archive of maritime trading and whaling

If you have enjoyed reading this post, check out previous ones about the Salvesen Archive…:

Cinema at the whaling stations, South Georgia August 2016

Maritime difficulties during the First World War – Christian Salvesen & Co. October 2015

Talk on the Salvesen Archive to members of the South Georgia Association November 2015

‘Empire Kinsley’ – 70th anniversary of sinking on 23 March 1945 March 2015

Pipe bombs, hurt sternframes, peas, penguins, stoways and cookery books: the Salevesen Archive July 2014

Whale hunting: New documentary for broadcast on BBC Four June 2014

Cataloguing the correspondence of Thomas Nelson & Sons (cont.)

Our intern Isabella has now finished her 10-week placement at the CRC, during which she was box-listing part of the records of Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd. Her thoroughness and fine attention to details made her perfect for the job. Luckily for us, Isabella enjoyed her placement so much that she decided to keep working on the collection as a volunteer! We are delighted that she is going to keep doing excellent work on this great collection. Here are a few more of her great finds.

Isabella working in the CRC reading room.

1. Jane Borthwick Letter: While every other letter in this bundle is written in black or dark blue ink, with edits often made with red ink, Jane Borthwick writes a letter here in an aesthetically appealing purple ink. The letter concerns a manuscript which she was enlisted to read, review, and recommend for either publication or rejection. Unfortunately for the author, Ms. Borthwick found the piece too dull to be printed. On the back of the letter there is slight evidence of handling where several ink stained fingers held the letter. While the marks are slight and it cannot be determined if these are the product of Jane herself, an employee of Nelson & Sons or of a later cataloguer or archivist, it stands as evidence of this letters connection to the people that have interacted with it, carrying its handling history on its surface. 1. Jane Borthwick’s letter

1. Jane Borthwick’s letter

2. R. Anderson Letter: A letter from R. Anderson displaying discoloration of paper, dust and dirt – Some of the correspondence we are working to catalogue requires light conservation methods before we can return them to storage. In this letter from an R. Anderson, one side shows how protected and covered paper ages as that side has been stored firmly pressed against another letter, while the other side reveals how long-term exposure to the elements of stacks can fade, damaged and color the paper. In order to attempt to combat this issue a small dry sponge is used to wipe away what dirt or dust can be wiped away, however, due to the age of the ink on the paper we must be careful not to take any of the ink off the page itself. This then becomes a conundrum of whether to maintain the precision of the ink or to treat the residue before it becomes a larger and more expensive issue.

2. R. Anderson’s letter

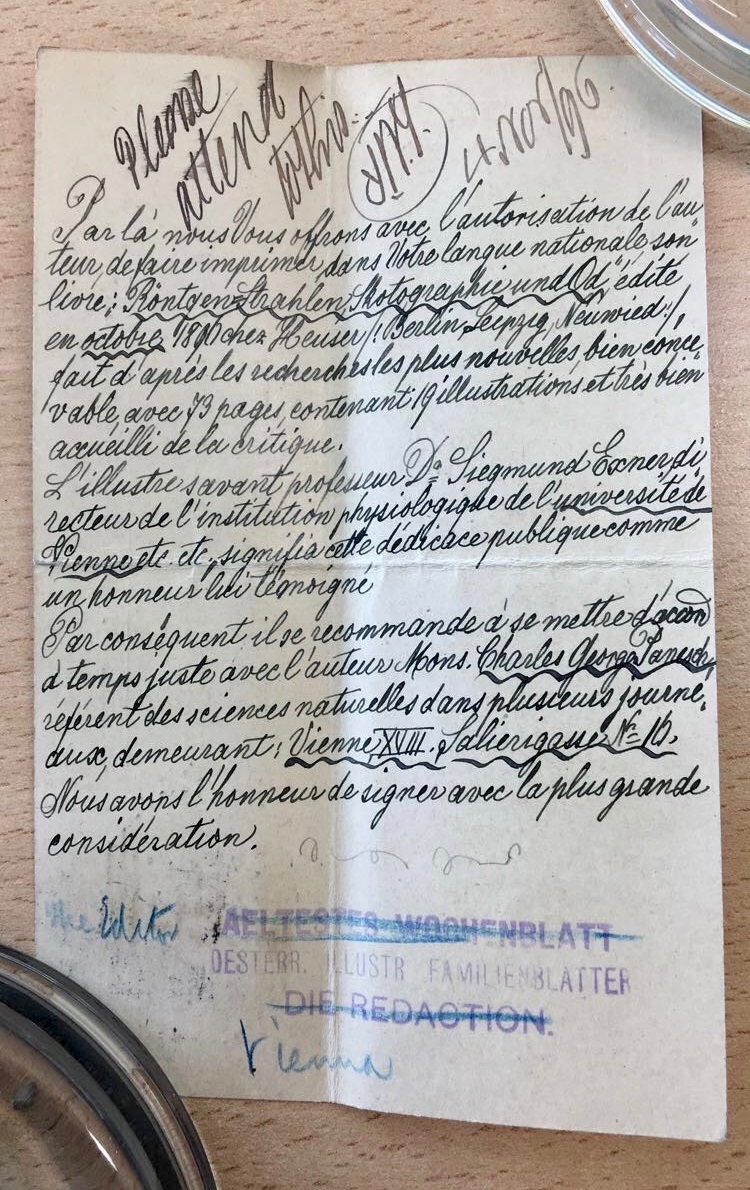

3. French Postcard: Here we have a postcard from Vienna written entirely in French. Unfortunately, our cataloguer does not read French and so help was requested from a fellow student from the Book History and Material Culture course, Eleanor Cambridge, as well as the cataloguer’s supervisor and resident Archivist with the Center for Research and Collections, Aline Brodin. The emersion of this postcard from the collection allowed for cooperation between postgraduates as well as Archivists to engage in a multi-national approach to decipher another element of the archive. This opportunity not only demonstrates the way archivists and cataloguers often work in tandem in order to contextualize information and collections, but it further speaks to the multi-national nature and reputation of Nelson & Sons.

3. French postcard

4. J. A. Bains Letter: Pictured here is part of a collection of nine letters sent from one J. A. Bains on highly personalized stationery decorated with fastidiously carved print images on one side. Despite the intricacy of the prints on the stationary, their appearance is not entirely a surprise as if you look to the right-hand side of the image you will see that Mr. Bains was a bookseller as well as a Stationer. Mr. Bains interactions with Nelson & Sons was such that he had been writing a biography on the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen and was very determined to see his piece published with their company alone. This sentiment was made plain to Mr. Brown, a manager at the company, in the final line of Mr. Bains letter from May 12th, 1896 writing, ‘I am determined that Messrs. T. Nelson & Sons shall publish it – even if I have to wait for months or years! I have spent too much labor (even if amateur) too much money and wandered too many miles to gather information to let it fall through.’ Bains was a jovial correspondent, often using exclamation points in his letters, reasserting that he would have no one else publish his work but Nelson and Sons, and on two occasions joking that if Nansen, who was on expedition at the time of these letters, did not return then his book would be the first biography published and probably a roaring success. Unfortunately, Mr. Brown did not return his enthusiasm as he rejected the opportunity to publish the work, multiple times, and so Mr. Bains took his biography to Walter Scott Publishing Co. Ltd. and the book was published in 1897.

4. J. A. Bains’s letter

5. Sophia Caulfield and Audrey Curtis Letters: Many of the manuscripts sent to Nelson & Sons were full of differing content and came from a variety of people throughout a number of countries. Audrey Curtis and Sophia Caulfield were two of those authors. Ms. Curtis submitted her manuscript of ‘a tale of the Huguenot persecution in France about the date 1685’ while Ms. Caulfield wrote about ‘little-known curiosities in the department of Natural History’ of London. Each woman worked on historical and amateur scientific novels. Curtis herself had previously been published by the National Society for her short story entitled “The Artist of Crooked Alley” as well as for her story for children titled “Little Miss Curlylocks”. Each woman was a fairly accomplished author by the time they came across Nelson & Sons for their publications with Ms. Caulfield identifying herself as one of the original writers for a popular magazine aimed at young women interested in science and politics. As well Ms. Caulfield included a written resume with her manuscript to Nelson & Sons of all that she had worked on which included compiling a dictionary of needlework, textiles, and lace, as well as editing magazine articles, and her latest book which had been shown at the Chicago “World’s Fair” as well as the ‘Great Paris Exposition’.

5. Audrey Curtis’s Letter

6. Rev. F. Docker Letter: The Reverend F. Docker, pictured here, was a religious short story author who sent several stories for potential publication to Nelson & Sons in 1896. Along with his letter and his manuscripts he included a newspaper clipping from The Christian Age newspaper bearing one of the stories which he had written as well as his picture. If you peer at the heading of the paper, you will see that it is identified as No. 1,268. -Vol. XLVIII.-26. and was published in ‘London, Wednesday, December 25, 1895’ meaning that the story Reverend Docker submitted to the publishers was in fact a Christmas installment.

6. Rev. F. Docker’s Letter

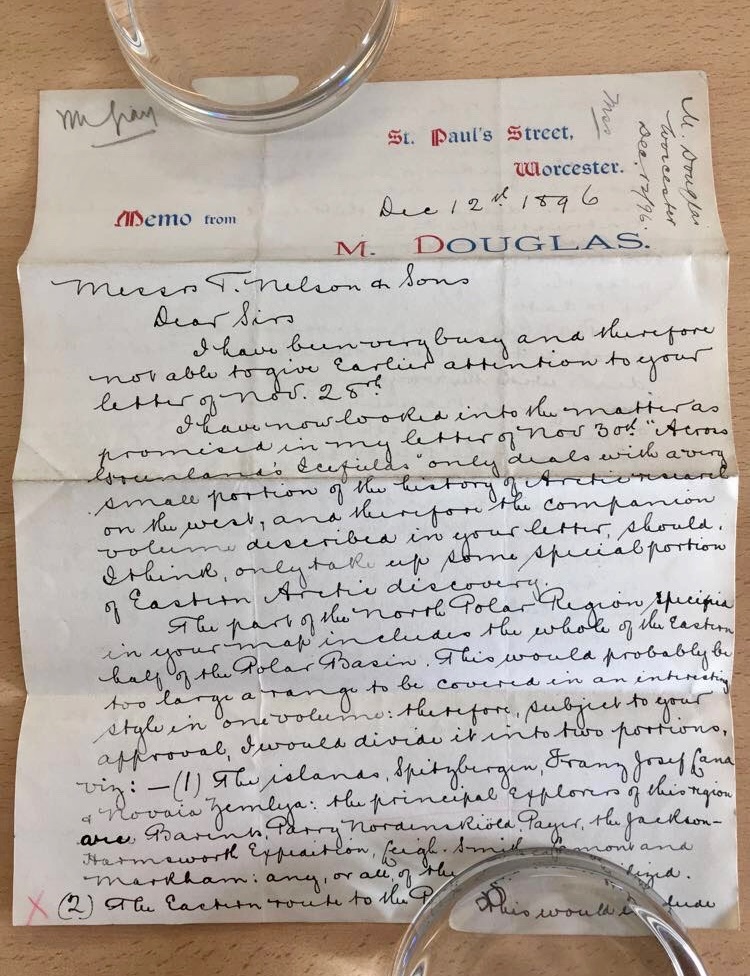

7. Miss M. Douglas Letter: Here we see another example of Nelson & Sons enlisting the help of an expert for practical scientific publications. M. Douglas was a woman who worked with Nelson & Sons when producing a new book about Arctic Exploration. She was the designated reader and critic for the configuration and aesthetic design of the maps illustrated in the book. Unfortunately, this letter does not give the reader any more background as to her work but rather it does prove she showed a high proficiency for spatial relations, math, and geography in order to conceptualize and stylize maps for the Arctic which in 1896 was still a relatively unknown climate. In her letter here she shows a high understanding of Polar currents as well as a strong familiarity with the literary histories of Arctic Exploration.

7. Miss M. Douglas’s letter

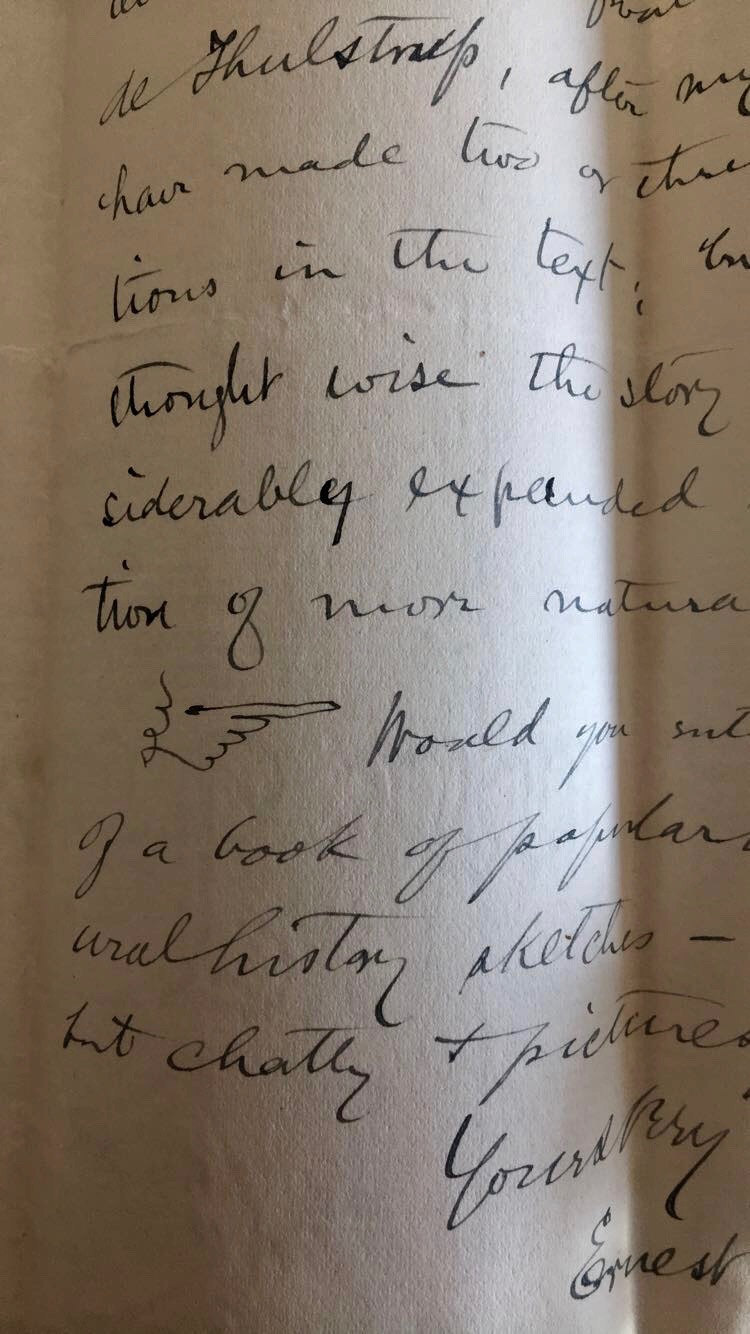

8. Ernest Ingersoll Book Submission: In 1896 Ernest Ingersoll submitted to Nelson & Sons his story entitled “A Railway Stowaway” which had previously been published in the United States by the well-known publishers of Harper & Brothers. In his letter Mr. Ingersoll offers Nelson & Sons ‘all rights outside the United States’ to the publication. While many authors include a full manuscript along with their letters, which they either request to be returned if they are rejected for publication, a gamble if the author has not written out or commissioned printed copies, Mr. Ingersoll included a small pocket copy of his story which was printed in the style of the Harper Collins 1882 edition. This particular copy was hand bound as you can see from the string threaded through the center pages and came complete with illustrations. The size of the copy enabled it to stay with the letter in this case, instead of the manuscript being returned or archived in a different location within the collection. This inclusion allowed us to not only understand the background of this submitted manuscript but also to collect the priority piece of knowledge that Nelson & Sons were offered sole rights to this piece for every publication outside of the United States. Unfortunately, Nelson & Sons decided to reject the offer. However, Mr. Ingersoll did not give up entirely and instead sent them a copy of one of his other stories entitled “The Ice Queen” which had been well received in the United States and which Harper & Brothers were willing to negotiate on copyright purchasing and illustrations expenses. While the last photo in the below series is not included in any copy of Ingersoll’s printed work, it is a wonderfully interesting example of marginalia which mimics medieval style. Referred to as a manicula, the hand design which was used to draw attention to specific passages, is used by Ingersoll here to identify the final paragraph of his letter.

8a. Ernest Ingersoll

8b. Ernest Ingersoll

8c. Ernest Ingersoll

8d. Ernest Ingersoll – manicula

Implementing ArchivesSpace

Meeting our Needs

Since the early 2000s we have been looking for suitable software to manage our archives in a holistic manner. We began to deliver online catalogues at this time via various project initiatives, with metadata encoded as EAD/xml, but this only dealt with resource discovery and was quite cumbersome. Moreover, along with other digital developments, the work inhabited one of a number of parallel silos.

As time moved on, we got better at developing systems to move different elements of work from the analogue to the digital but were still some way off developing or finding a comprehensive, robust and sustainable way to join things up in a meaningful way. This changed when we began to investigate Archivists’ Toolkit in 2011. Although we had looked at it in one of its earlier versions, we were surprised to see how much subsequent developments had brought it quite close to ticking everything on our wish list. It was lacking a resource discovery layer but a successor product, ArchivesSpace, was already planned and would include this.

From Archivists’ Toolkit to ArchivesSpace

We therefore began looking at Archivists’ Toolkit in more detail, assessing issues such as functionality and usability but also those of sustainability and interoperability. It scored very highly, high enough for us to be able to make the business case to commit to ArchivesSpace and obtain the internal funding to sign up as Members.

The involvement of the profession in the development of ArchivesSpace has been and continues to be crucial. What has been developed is not just other people’s idea of what the product needs to be but what we as archivists actually require. Although heavily influenced by the predominant US partners and the specifics of US practice, it has been developed in way that is equally intelligible to others and easily customisable to reflect local needs and terminology.

Priorities and Impact

We originally focused on moving our behind-the-scenes work over but then switched to frontloading our resource discovery, migrating existing EAD xml files and also retro-converting a wide range of old spreadsheets, databases and similar. In terms of impact, this both provides evidence that our business case was sound but, most importantly, meets growing user expectations of what and online catalogue should deliver.

Phase one saw the delivery of nearly 17,000 catalogue records along with over 22,000 authority terms. We still have more to add, along with a whole range of management metadata about accessioning, locations etc. This will feature in Phase 2.

Because the source metadata has been drawn from a variety of legacy sources, there are issues of consistency and quality to be addressed. These are outstanding issues which could never be solved just by getting the metadata into ArchivesSpace. However, with all the metadata now in one place we can now look to quantify and rectify them. Experience told us that’s users would often rather have partial metadata rather than no metadata at all so we chose to go for a warts and all approach, only correcting what was obviously erroneous at this stage.

Community and Participation

We are proud to have signed up as the first European partner and the support we have had from a growing community of ArchivesSpace users and developers. This discussion is also two-way, with us feeding ideas back for future development.

Locally we are also more fully integrated into developing solutions that deliver all our collections online, through a suite of applications and interface that work together, improving user experience and improving how we manage the collections themselves.

Next Steps

We still have lots to do with the system to leverage the full functionality of the system and fully showcase our amazing archives collection. So watch this space.

New acquisition: Further papers of Alexander Craig Aitken

The mathematician, statistician, writer, composer and musician, Alexander Craig Aitken, was born in Dunedin, New Zealand on 1 April 1895. He was of Scottish descent. He attended Otago Boys’ High School from 1908 to 1912. On winning a university scholarship in 1912 he went on to study at the University of Otago in 1913, enrolling in Mathematics, French and Latin. Studies were cut short by the 1914-1918 War however and he enlisted in 1915 serving with the Otago Infantry. Aitken saw action in Gallipoli and Egypt, and he was wounded during the Battle of the Somme. After his hospitalisation, he returned to New Zealand in 1917.

The mathematician, statistician, writer, composer and musician, Alexander Craig Aitken, was born in Dunedin, New Zealand on 1 April 1895. He was of Scottish descent. He attended Otago Boys’ High School from 1908 to 1912. On winning a university scholarship in 1912 he went on to study at the University of Otago in 1913, enrolling in Mathematics, French and Latin. Studies were cut short by the 1914-1918 War however and he enlisted in 1915 serving with the Otago Infantry. Aitken saw action in Gallipoli and Egypt, and he was wounded during the Battle of the Somme. After his hospitalisation, he returned to New Zealand in 1917.

On the completion of his studies in 1920, Aitken became a school-teacher at Otago Boys’ High School and the same year he married Winifred Betts the first lecturer in Botany at the University of Otago where he also did some tutoring. Then, encouraged by a professor of mathematics at the University, he gained a postgraduate scholarship which brought him to Edinburgh University in 1923. His thesis on statistics gained him the degree of D.Sc. in 1925 when he also joined the University staff as a lecturer in Statistics and Mathematical Economics. In 1937 he was promoted to Reader, and in 1946 was appointed to the Chair of Mathematics.

Aitken’s publications include: jointly with H. W. Turnbull, The theory of canonical matrices (1932); with D. E. Rutherford, a series of Mathematical Texts; wartime experiences in Gallipoli to the Somme: Recollections of a New Zealand infantryman (1963); and, posthumously To catch the spirit. The memoir of A.C. Aitken with a biographical introduction by P.C. Fenton (1995). He made many important contributions to the many fields of his subject, particularly in the theory of Matrix Algebra and its application to various branches of mathematics. In his time, Professor Aitken was one of the fastest mathematical calculators in the world.

While at school, Aitken had learned to play the violin, and later on in life he played both the violin and viola and composed pieces for performance by university groups. He died in Edinburgh on 3 November 1967.

Shortly before Christmas we acquired a further tranche of Aitken’s papers. These include a number of original mathematical manuscripts, correspondence, legal documents, offprints, publications and photographs. Amongst these is a review by Aitken of Sara Turning’s “Alan Turing”.

At the moment we still have to look through the collection, box it up and create a basic handlist. Once this is done it will be available for consultation.