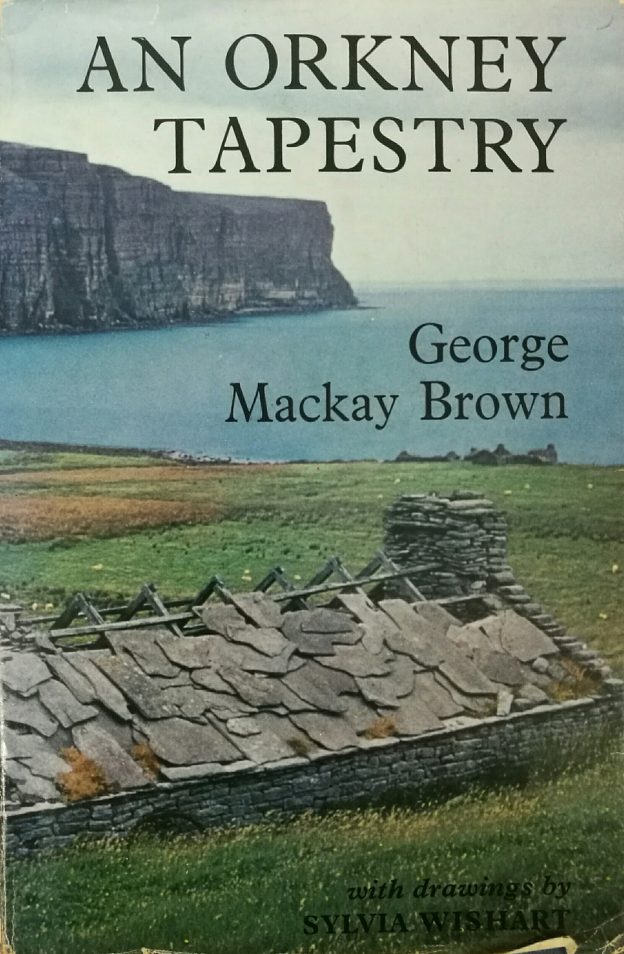

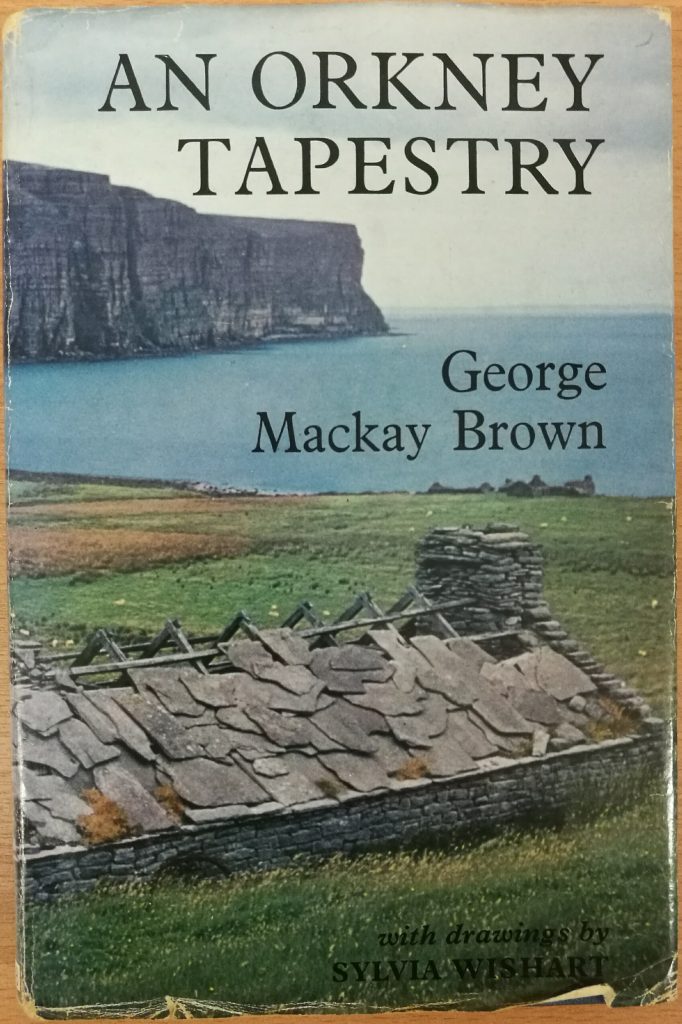

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of two of George Mackay Brown’s landmark publications, An Orkney Tapestry and A Time to Keep. While Brown was already well established as a poet, these works made his reputation as a master of prose.

Unusually, An Orkney Tapestry was a commissioned publication. In late 1967, literary agent Giles Gordon approached Brown on behalf of Victor Gollancz publishers to inquire whether he might be interested in writing a general guide to his native Orkney. Although it was not the kind of work that appealed to Brown, Gollancz were offering a generous advance, and it presented an opportunity of visiting parts of the Orkney archipelago that he had not previously seen. The manuscript that Brown eventually submitted, however, was very far from a conventional guidebook. Instead, in An Orkney Tapestry, Brown wove prose, poetry, and drama together to commemorate the stories and traditions that had forged the character of the islands and their inhabitants.

The book consists of six sections: a polemical sketch of contemporary Orcadian life; a history of the ‘ghost village’ of Rackwick; a retelling of crucial episodes from the Orkneyinga Saga; an essayistic account of Orkney folklore; a short story-like evocation of a ballad singer’s performance at the Renaissance court of Earl Patrick Stuart; and a play ‘The Watcher’ concerning the apparition of an angel in an everyday Orkney setting.

Brown’s intention was to stress the importance of stories in creating a community and holding it together. A community cuts itself off from these formative stories at its own peril (p. 23), and Brown feared that the life of contemporary Orkney was increasingly meaningless (p. 19). An Orkney Tapestry is as much a jeremiad as a celebration. Time and again, Brown rails against progress–or rather a dogmatic, utilitarian ‘religion’ of Progress–as a ‘cancer’ that ‘drains the life’ out of ‘an elemental community’ (p. 53). He laments the loss of the old Orcadian speech and the uniformity created by compulsory education and the omnipresent new media of radio and television. With An Orkney Tapestry, he hopes to reawaken Orcadians to their history and traditions, and to inspire them to return to their life-giving roots.

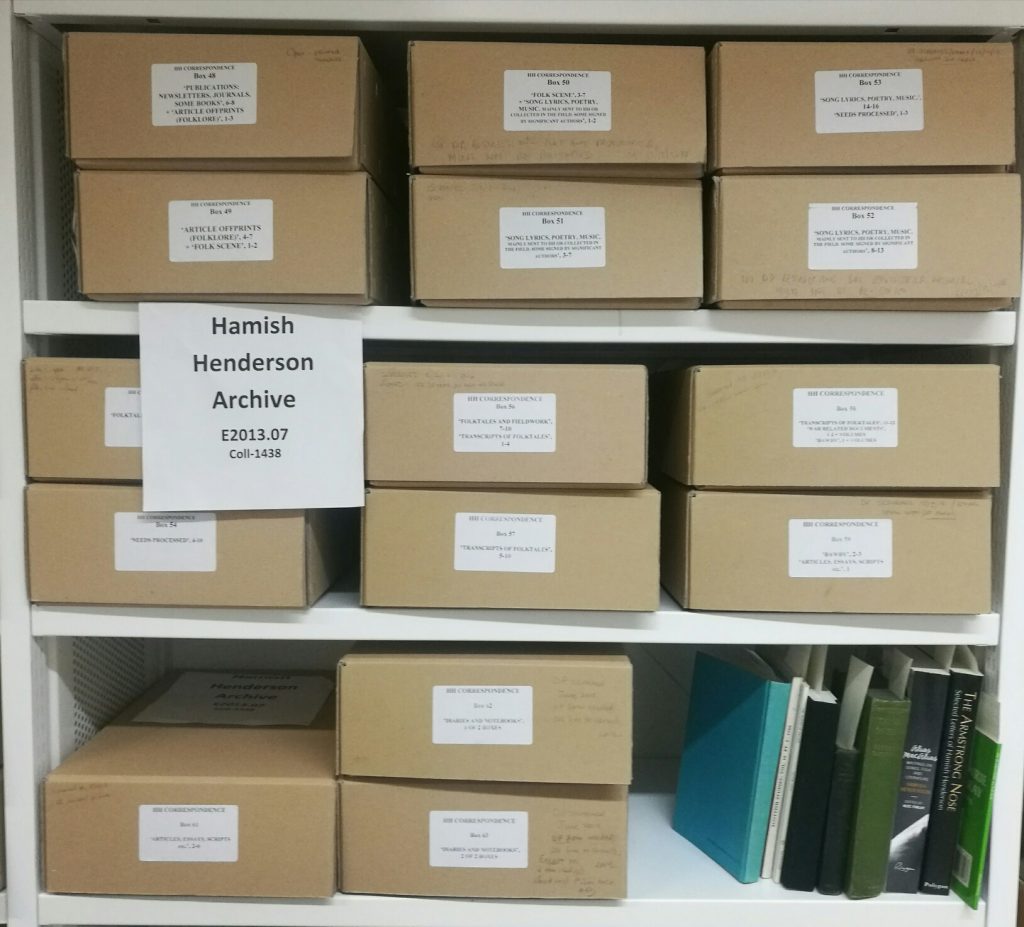

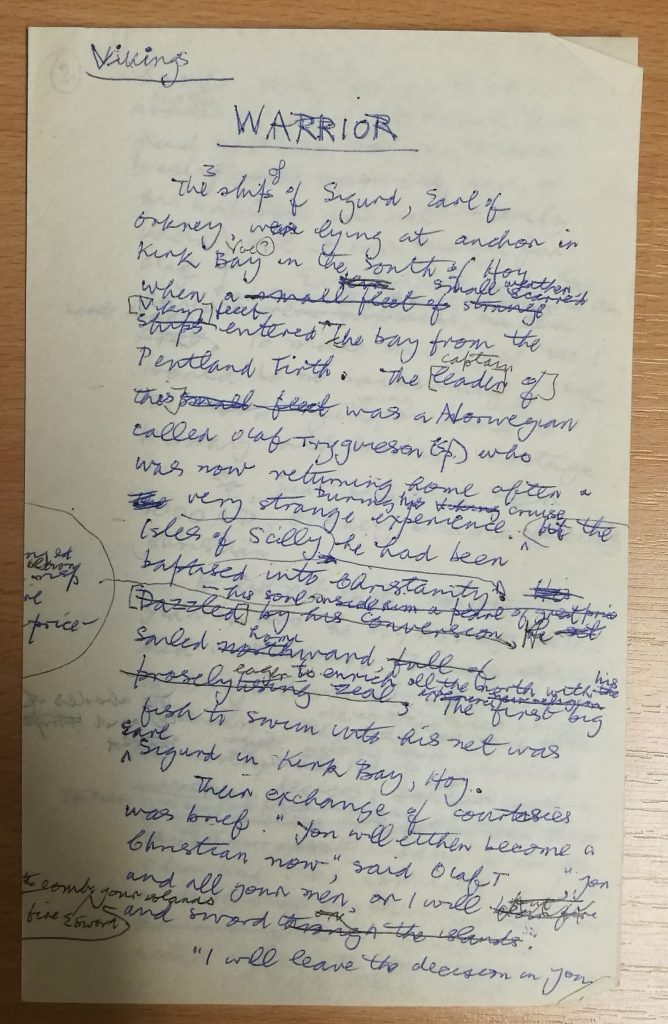

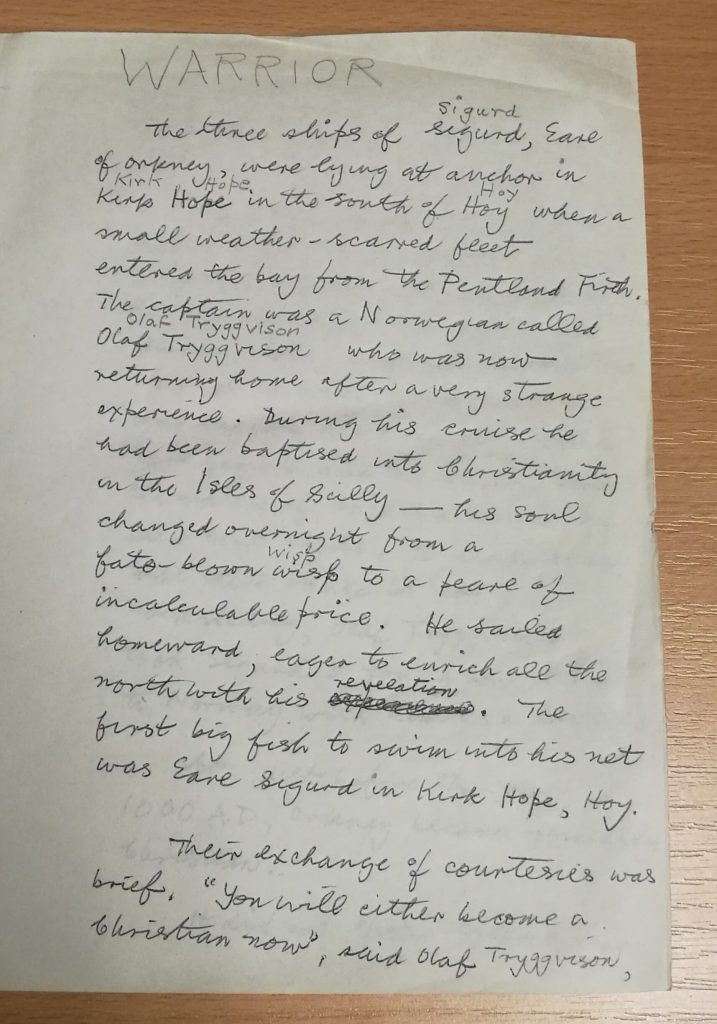

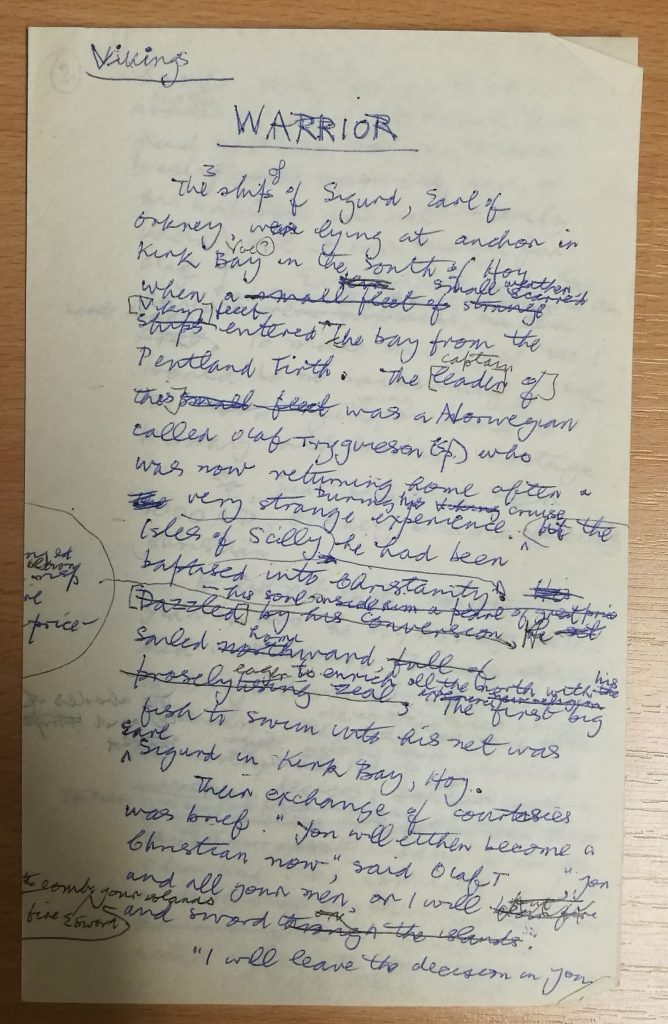

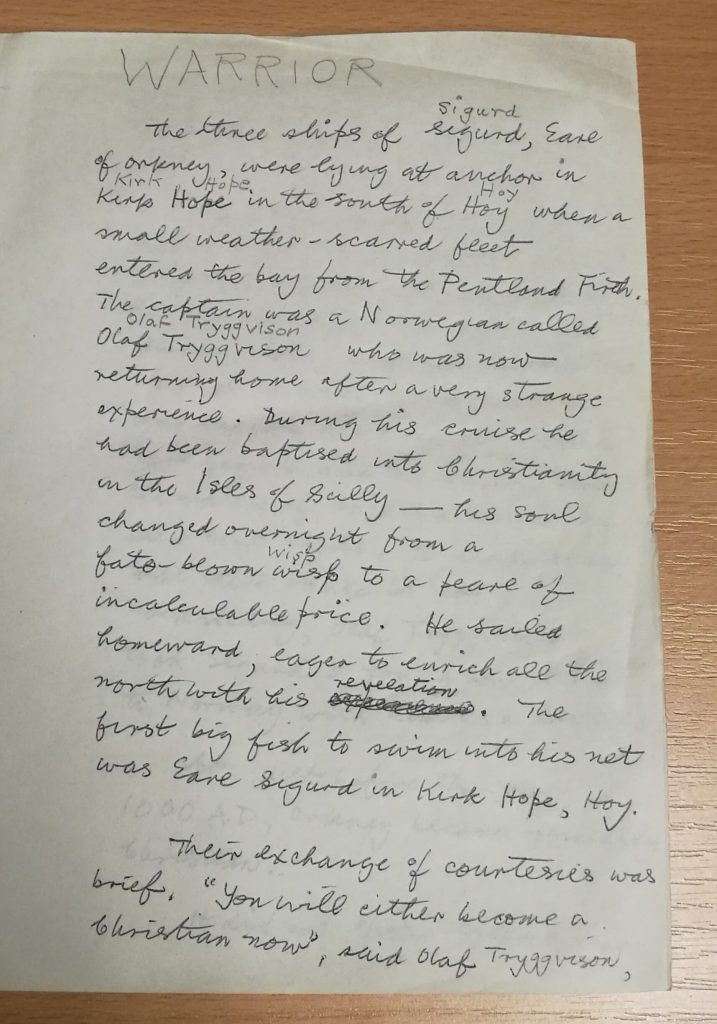

Edinburgh University Library hold a much-corrected MS draft of An Orkney Tapestry (Gen 1868/5) together with a fair copy with instructions for a typist (Gen 1868/4).

-

-

Part of MS draft of ‘An Orkney Tapestry’

-

-

Fair copy of same

We also hold George Mackay Brown’s letters to fellow poet Charles Senior (E2000.11), in which he traces the genesis of An Orkney Tapestry. In a letter of 28 December 1967, Brown tells Senior that he has been commissioned to write ‘a book about Orkney’. It is not ‘the kind of thing I like doing’ but should ‘bring in a couple of hundred quid or so’. On 8 January 1968, he reports that his usual publisher Chatto & Windus have reluctantly granted him permission to write for Gollancz, but Brown is unsure ‘whether I’ll be good at that sort of thing or no’. By 13 January, his doubts have grown: ‘I’m not good at patient research and reappraisal and I have no idea where the drift of history is taking the Orcadians’. He hopes to hit upon some ‘valid & original way’ to tackle the commission. On 20 January, he declares that he is determined, at least, not to write ‘some kind of a glorified guide book’. By Candlemas Day (2 February), the book is clearly beginning to take shape. It will be ‘highly impressionistic’ and entirely free of statistics: ‘I shun figures and tables as I would the devil’. He is planning a chapter on Rackwick, and a section contrasting a medieval or renaissance bard with the contemporary Orkney poet Robert Rendall. By 9 February, he reveals that he has been working on the ‘Orkney book’ all week, and has finished the first draft of the chapter on Rackwick (‘interlarded with poems’). This has left him ‘with a flush of achievement’, though he suspects that closer scrutiny may discover ‘a hundred flaws’. On 16 February, he laments the difficult of translating (‘or, rather, freely adapting’) Norse heroic verses for the third chapter of An Orkney Tapestry. These ‘stretched all my faculties to the utmost’ but ‘it’s good for writers to tackle something hard now and again’. Unfortunately, the correspondence with Senior is suspended at this point, as Senior was now, in fact, living close by in Orkney. These few letters, however, give a vivid impression of how An Orkney Tapestry swiftly evolved from impersonal commission to personal vision.

Within a fortnight of publication, An Orkney Tapestry had sold over 3,000 copies. One of its first readers, composer Peter Maxwell-Davies was so transfixed by Brown’s prose, that he was inspired to move to Orkney and make it his base for the rest of his life. Edinburgh University holds manuscript librettos for three works that Brown wrote for Maxwell-Davies: Apples and Carrots (MS 2846/4/2), Lullaby for Lucy (MS 2843/8/1), and Solstice of Light (Gen. 2134/2/4).

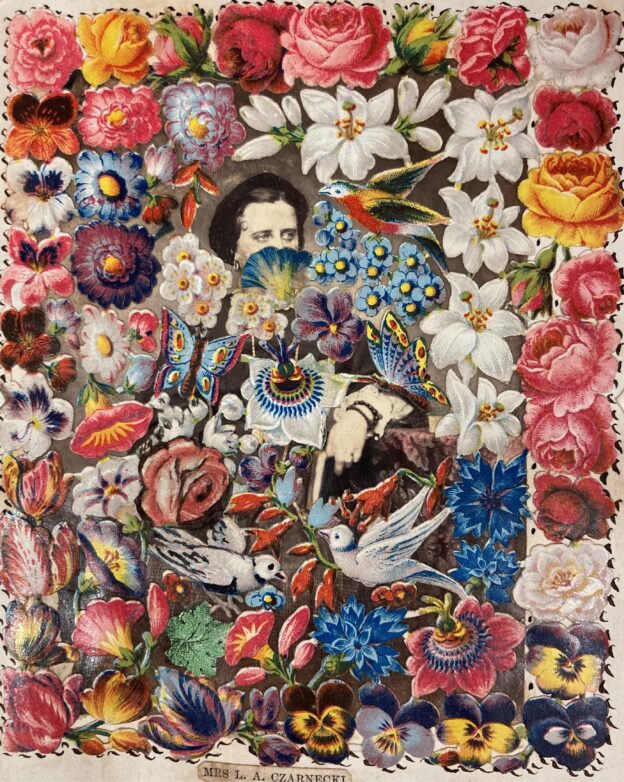

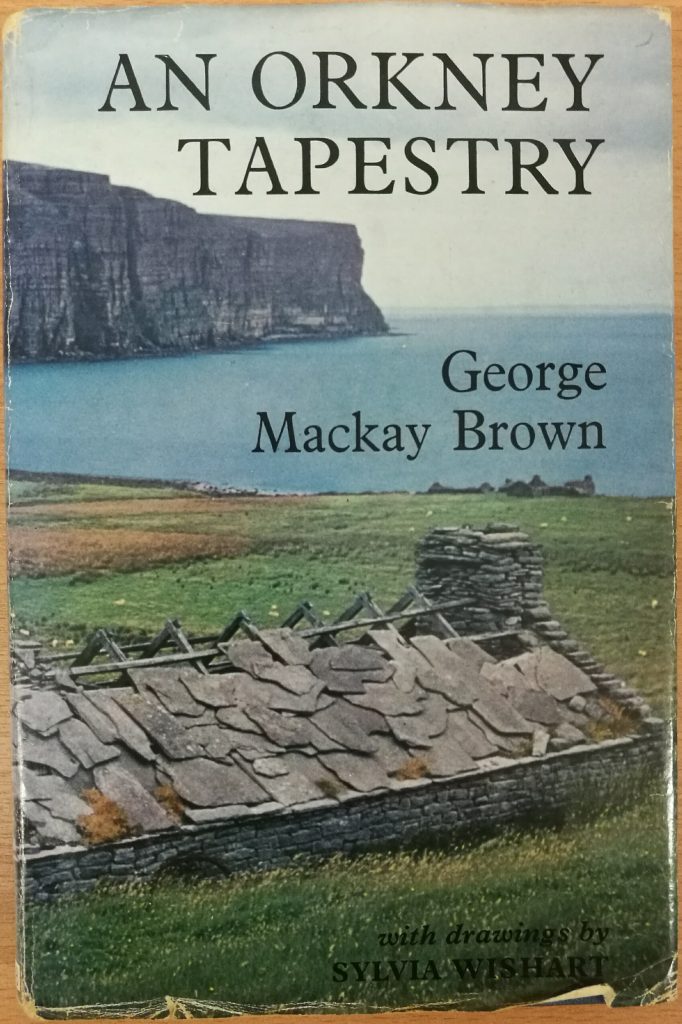

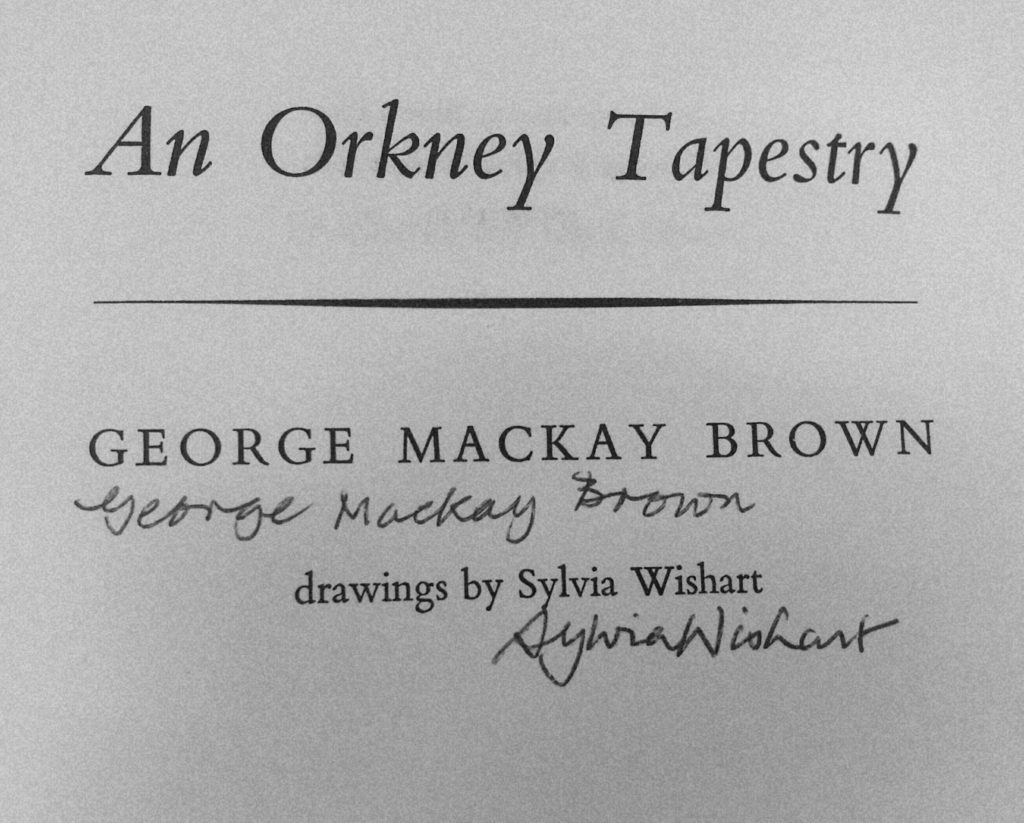

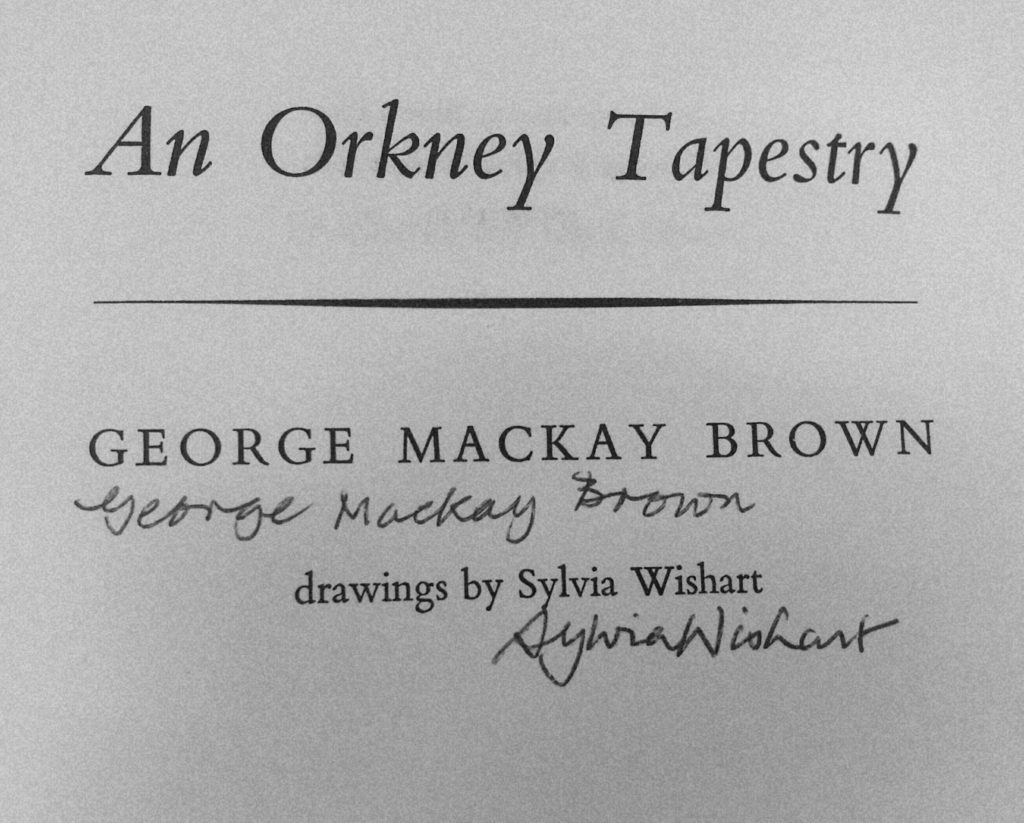

Another enthusiastic reader was veteran poet Helen B. Cruickshank. We hold Cruickshank’s well-thumbed copy of An Orkney Tapestry (JA3388), inscribed on the title-page by Brown and by artist Sylvia Wishart (whose illustrations for An Orkney Tapestry first brought her to prominence). There is also a brief letter from Brown on the half-title page, congratulating Cruickshank on the receipt of an honorary M.A. from Edinburgh University. A further letter from Brown in our Helen Cruickshank Papers (Coll-81) grants Cruickshank permission to quote a line from An Orkney Tapestry in her memoir Octobiography (Montrose: Standard, 1976): ‘Decay of language is always the symptom of a more serious sickness’. What Brown says of the decay of Orcadian speech (An Orkney Tapestry, 30), Cruickshank applies to the decline of her native Scots (Octobiography, p. 77).

-

-

Helen B. Cruickshank’s copy of ‘An Orkney Tapestry’

-

-

Title page of Helen B. Cruickshank’s copy of ‘An Orkney Tapestry’

The commercial success of An Orkney Tapestry was largely matched by critical approval. Seamus Heaney praised it as ‘a spectrum of lore, legend and literature, a highly coloured reaction as Orkney breaks open in the prisms of a poet’s mind and memory’ (Listener, 21 August 1969). For J. K. Annand, it was ‘one of those rare books which capture and convey the essential character of a place’ (Akros, January 1970). Not everyone, however, was entirely convinced. Robin Fulton, in the New Edinburgh Review (November 1969), felt that the problems raised by Brown ‘deserve more serious treatment than can be afforded by polemics and jeremiads’ and wondered ‘how closely in touch’ Brown was ‘with the way of life he professes to reject’. Brown rails against progress as a ‘new religion’ but ‘in fact who does in 1969 naively accept such a belief?’ (p. 6). Similarly, Janet Adam Smith felt that ‘Mr Brown is a far better poet than preacher and some of his diatribes on the present run too glibly’ (Times, 12 July 1969).

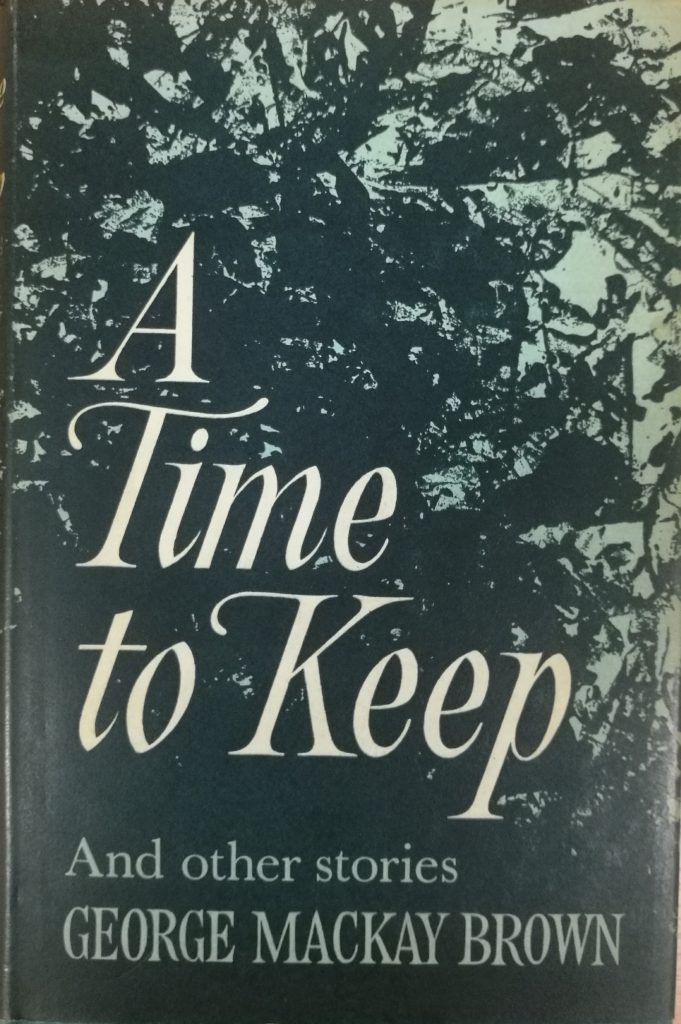

No such doubts were expressed about Brown’s second major publication of 1969, A Time to Keep, his second short-story collection after A Calendar of Love (1967). Alexander Scott wrote that Brown ‘gives more fundamental insights into our common humanity in even the shortest of his stories than will be found in a hundred full-length fictions of the conventional kind’ (Lines Review, 28 March 1969). Janice Elliot described him as a ‘precise, poetic, and dazzling writer’ (Guardian, 7 February 1969). Paul Bailey wrote the stories ‘often brought me close to tears’ and that there ‘are few writers alive today with the courage to be so simple and direct, or with the talent—the sheer, unforced talent—to lighten up the most humdrum detail’ (Observer, 2 March 1969). Even Robin Fulton, despite some reservations about the volume as a whole, declared that its strongest tales were ‘among the finest stories written by any Scottish writer’.

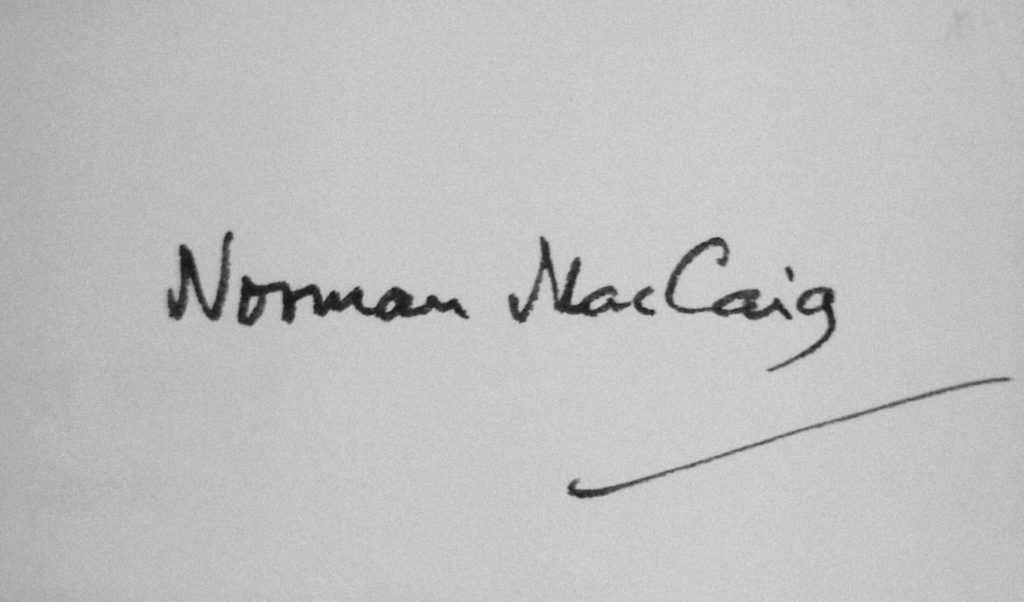

We do not hold any manuscripts or working papers relating to A Time to Keep. We do, however, have Norman MacCaig’s personal copy of the volume, signed by MacCaig on the half-title page.

-

-

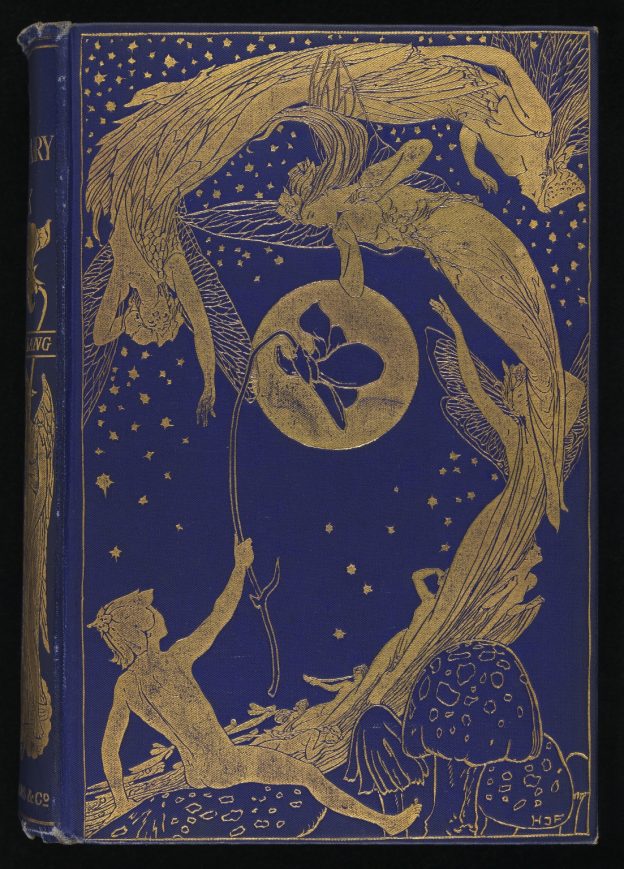

Norman MacCaig’s copy of ‘A Time to Keep’

-

-

Norman MacCaig’s signature on his copy of ‘A Time to Keep’

For further information on our Papers of George Mackay Brown, see:

Scottish Literary Papers

Sources (other than previously cited)

Timothy Baker, George Mackay Brown and the Philosophy of Community (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009)

Maggie Fergusson, George Mackay Brown: The Life (London: John Murray, 2007)

Berthold Schoene-Harwood, The Making of Orcadia: Narrative Identity in the Prose Work of George Mackay Brown (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1995)

Hilda D. Spear, George Mackay Brown: A Survey of his Work and a Full Bibliography (Lewiston: E. Mellen Press, 2000)