My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that are currently working on the Dc and Dk collections. I’m a part-time Masters student in the History, Classics and Archaeology department, and I’m just finishing up the first year of the Late Antique, Byzantine, and Islamic Studies course, which is an interdisciplinary degree. As you might imagine, that covers quite an eclectic range of subjects, and I have a variety of different research interests coming from a History and Literature background. During my degree, I spend quite a lot of time in the History and Divinity schools, so this internship was especially appealing as it’s allowing me to put my (limited) Latin skills into practice!

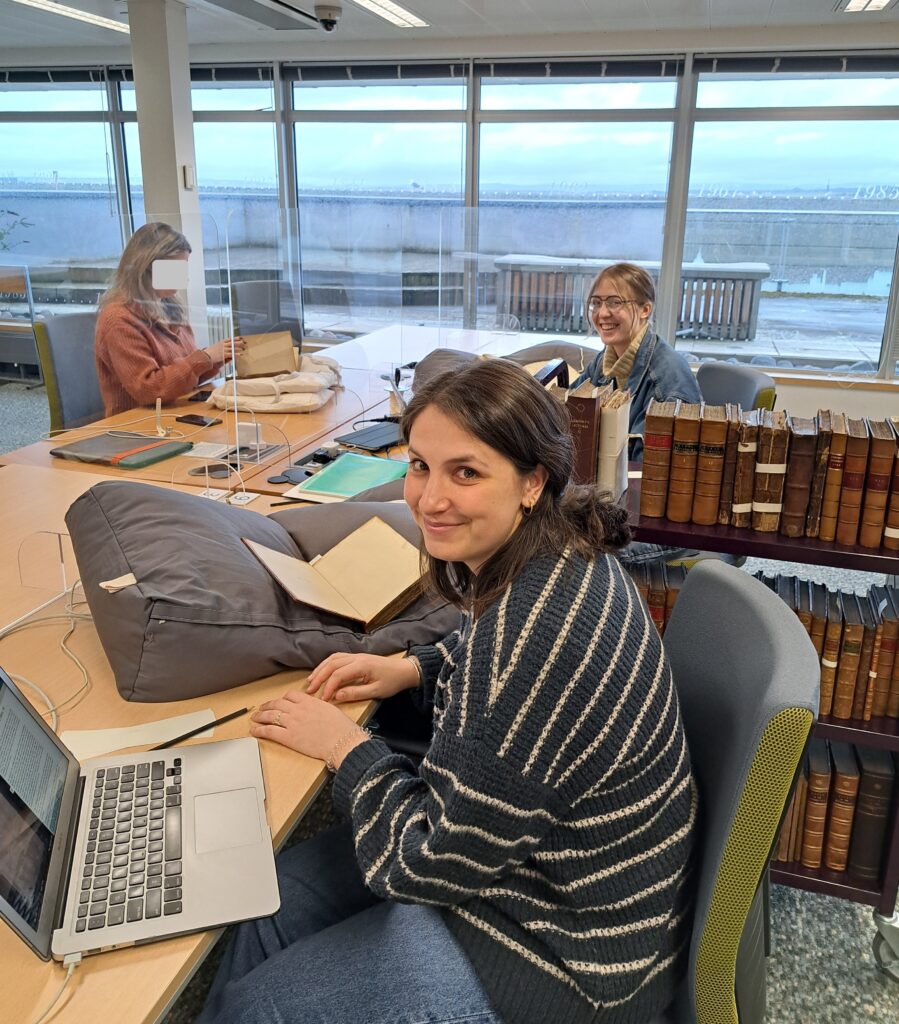

Emily working on the Dc sequence in the CRC Reading Room.

I did my undergraduate degree at the University of Edinburgh, so I’d previously used the Centre for Research Collections to look at some books related to Machiavelli and the Lothian Health Archives, but I hadn’t conducted any individual research there myself. I did have a session there in recent weeks independent from my internship as part of a seminar on Islamic esotericism, so I got to look at some of the CRC Arabic and Persian collections, which proved to be absolutely fascinating. They actually have an edition of the Quran that would fit into the palm of my hand – it’s best not to think too hard about the logistics of creating something like that – years of work and immense eye strain, no doubt. I’ve also spent a little time in various archives around Edinburgh, including the Royal College of Physicians on Queen Street, so I was fairly familiar with reading rooms beforehand.

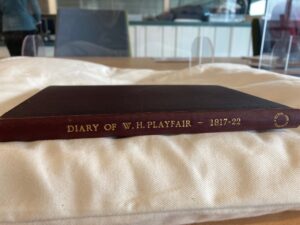

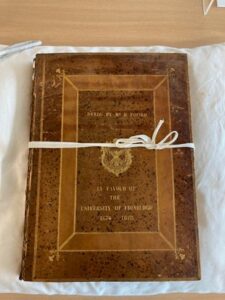

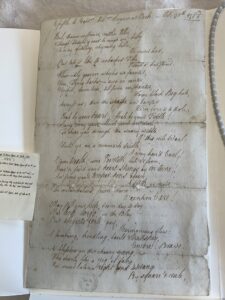

We’re now four months into the project, and we’ve just last week completed the Dc collection, which proved to be a fascinating look into the history of Edinburgh and of the University itself. Coming from a Literature background, I’ve been especially enamoured with some of the more famous names to be featured in the Dc collection, including Percy Bysshe Shelley, Robert Burns, and William Wordsworth. Many of the volumes we looked at include sheafs of letters, files, and correspondence, some of which were from some of the more famous names of the day. I’m sure Maddie can attest to me spending ages poring over various letters and such that I’ve stumbled across.

Some interesting letters and poems by Burns, Shelley and Wordsworth respectively.

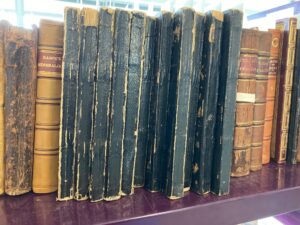

Thus far into the internship, Maddie and I have come across some fascinating books, including books on alchemy, science, and the history of the University, and my interest was piqued by the sheer amount of books in the collection that were written in Icelandic. However many you’re thinking, I can guarantee that there were more, including a saga on Nordic kingship. Exactly how the University accumulated so many Icelandic books is a mystery that I’m still working on, but it’s a fascinating discovery. I also stumbled across a version of Julian of Norwich’s ‘Revelations of Divine Love’ dating to approximately the seventeenth century, a woman whose life I find particularly interesting – an East Anglian anchorite and English mystic dating to the fifteenth century. Tucked away in the collection there was also a letter regarding the marriage of Mary, Queen of Scots to the French dauphin, which was, in all likelihood, contemporary. And as someone who has a particular interest in the history of medicine, I also found some interesting paraphernalia relating to the invention of anaesthesia, including a photo of the first child to be born whilst their mother was anaesthetised during the birth.

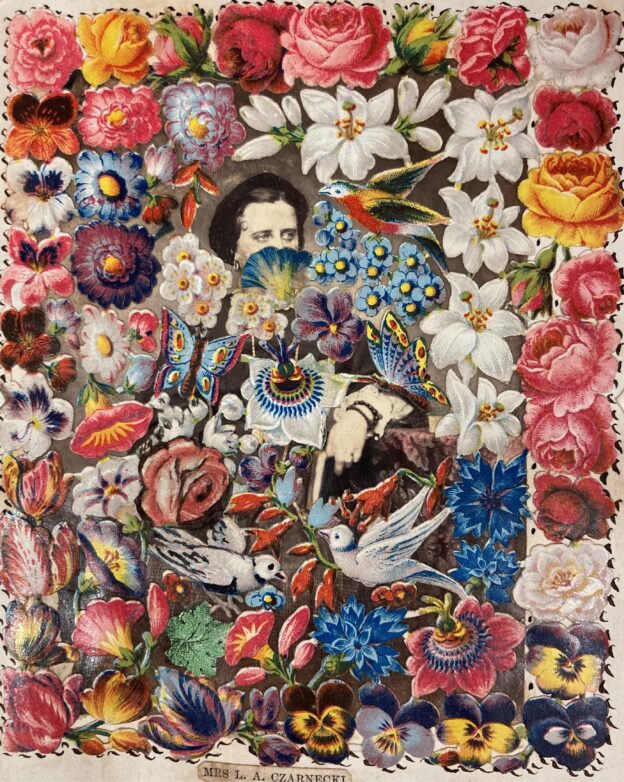

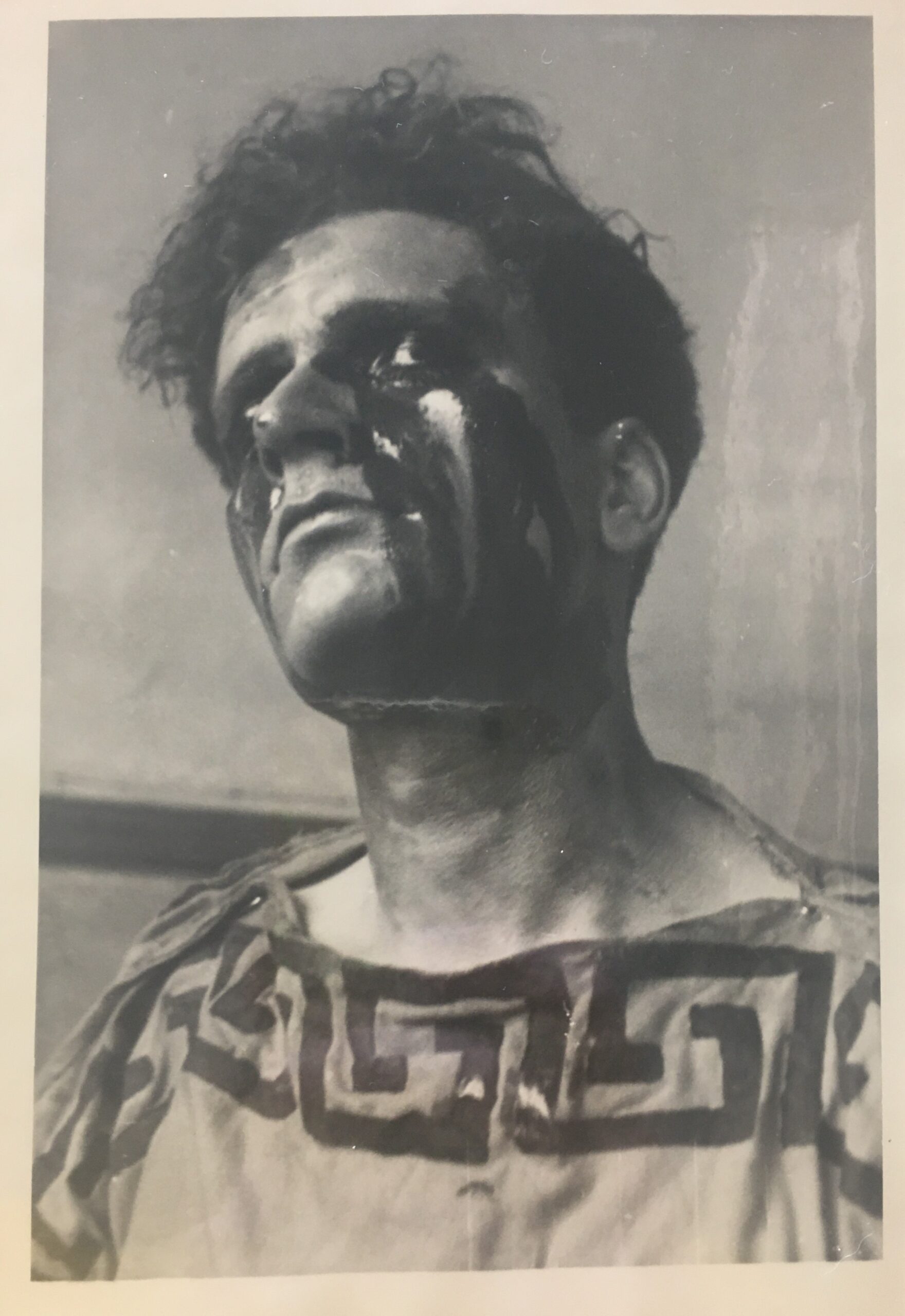

I always like stumbling across photos tucked in the volumes, especially in collections of letters, as I feel like it gives a sense of the person who wrote them. In one collection of letters, there was a photo of an old soldier and aristocrat, alongside other personal effects donated by his family (including an invitation to the Duke of Wellington’s funeral and Queen Victoria’s coronation!). Another volume was written by a student here in the early twentieth century, and included photographs of his regiment – all of whom were fellow students at the University as well. As such, it really gives a sense of who created these volumes and what was important to them – in this case, he wanted to commemorate his friends and brothers.

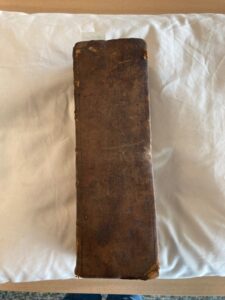

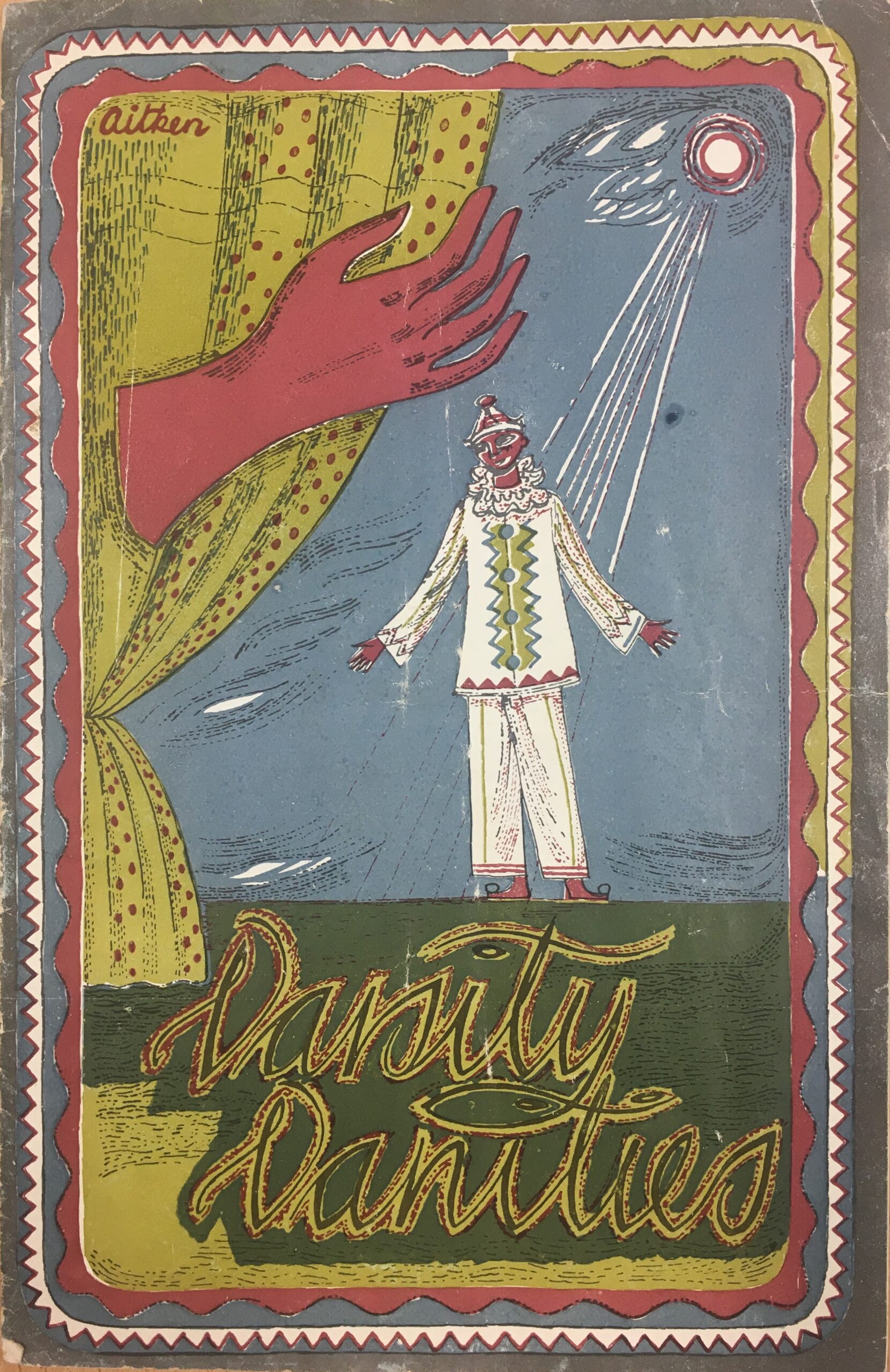

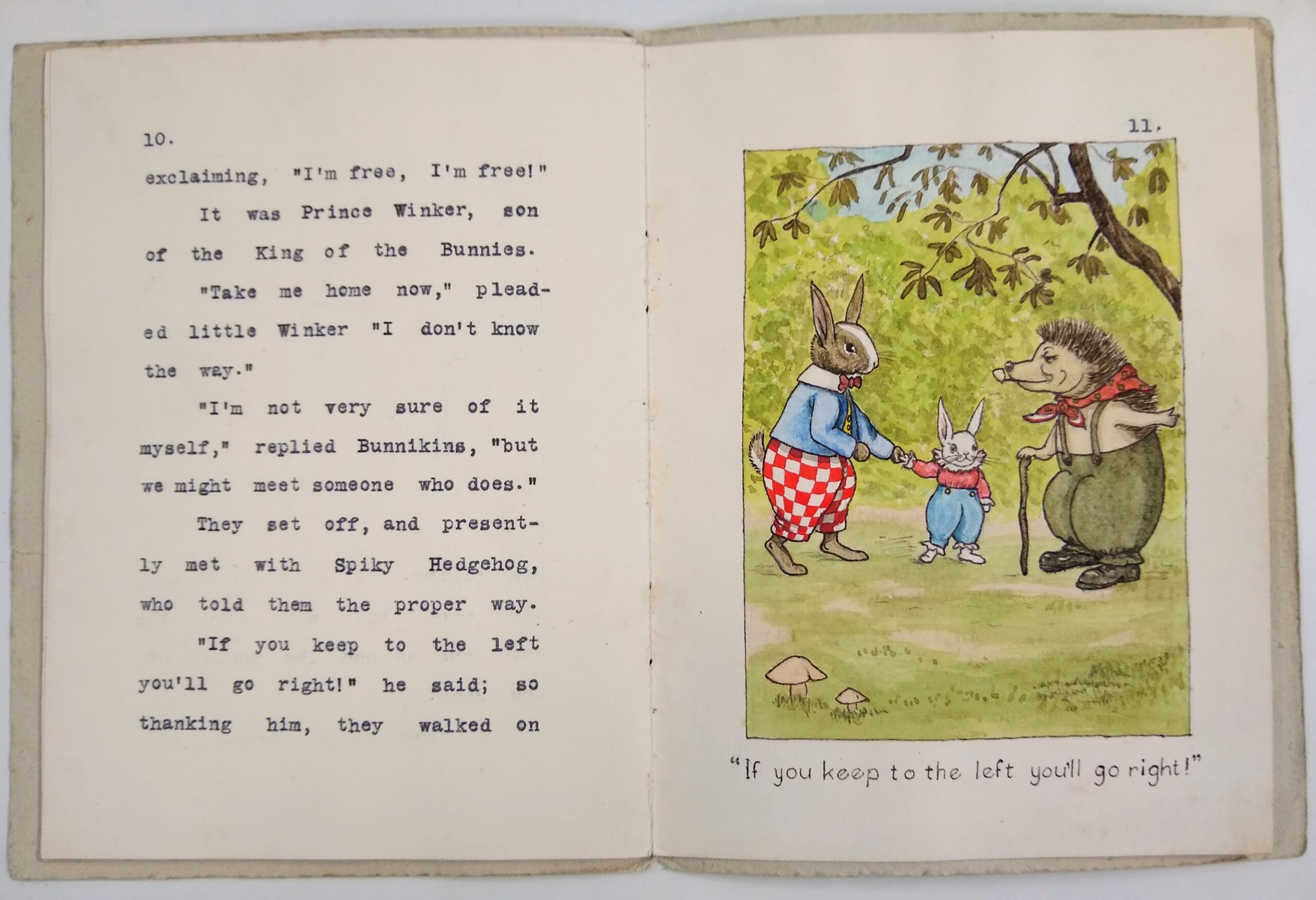

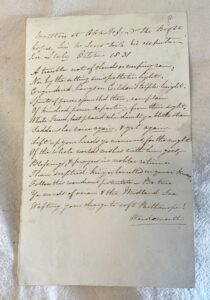

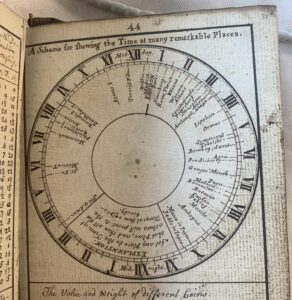

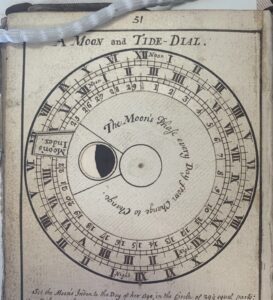

Photos and illustrations have been particularly prominent within this collection, whether it’s scribbled doodles in old textbooks (not so different from more modern student notes) to scientific diagrams illustrating different theorems. I’ve found a variety of different illustrations within the Dc collections, ranging from quick scribbles to beautifully detailed fly-leaf illustrations – so detailed, in fact, that it took me a while to figure out that it wasn’t printed.

Hand-drawn or printed? Hand-drawn, it turns out.

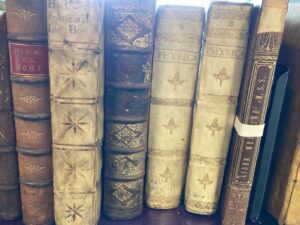

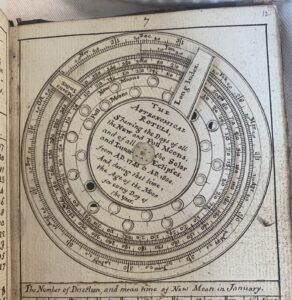

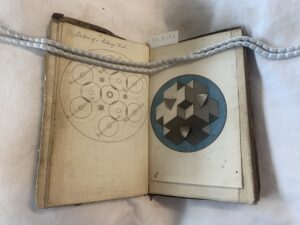

With the prevalence of scientific notes in the collection, many of the volumes also featured detailed illustrations which were used to explain various biological, chemical, and physical concepts. Many of these works were by the more famous scientific names associated with the University – and at the very least, names that a visitor to the King’s Campus would be familiar with, such as Joseph Black and Colin Maclaurin. A particular favourite of mine was a volume on metaphysics that had moveable parts to help explain different concepts.

Three different scientific diagrams, all with moveable parts.

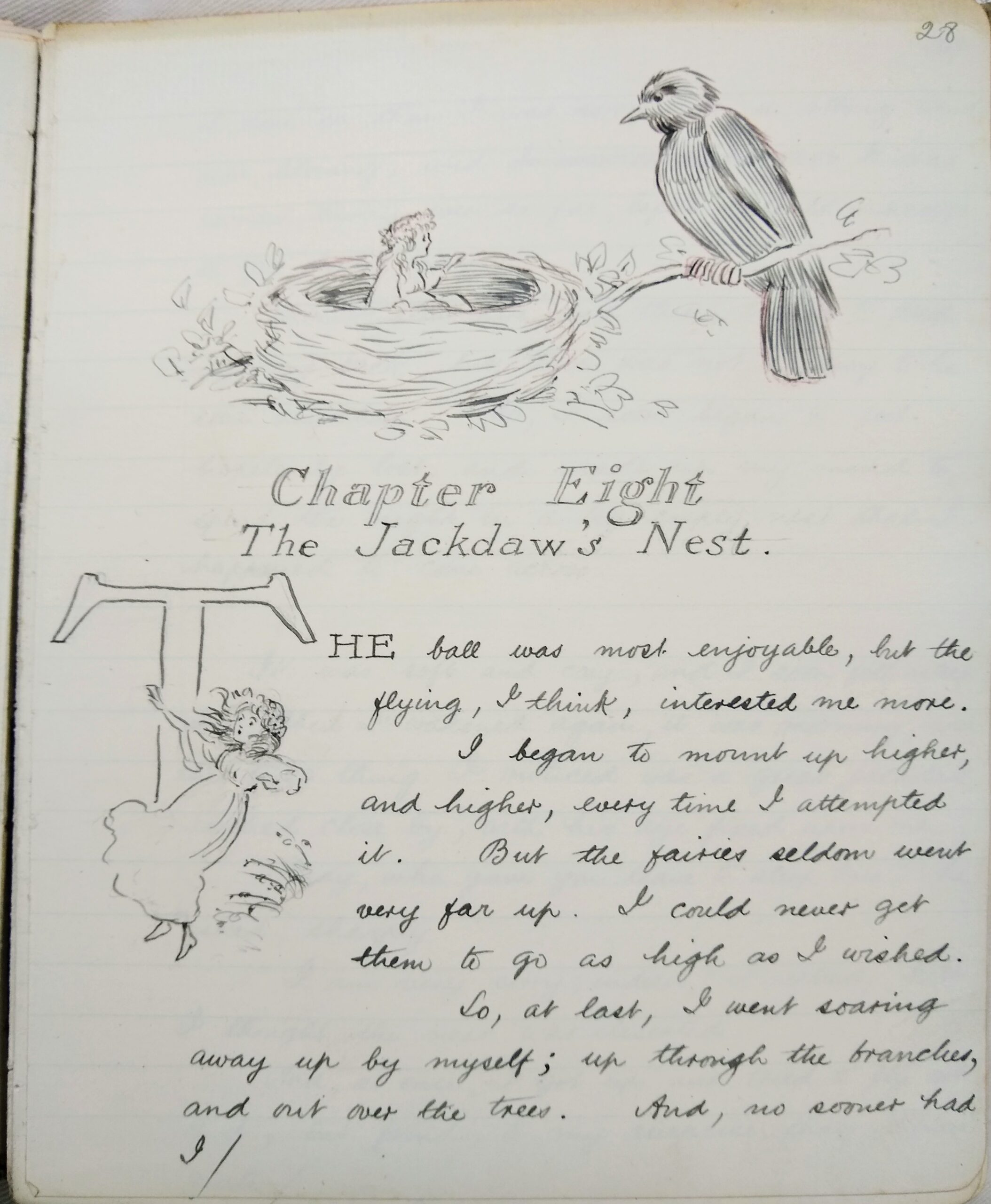

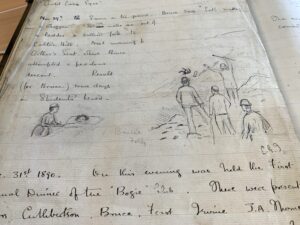

One thing that these particular collections have in abundance is minute books from various clubs and societies associated with the University. Although seemingly slightly tedious, Dk.1.4 proved an especially interesting find, as someone had taken the time to illustrate the minutes. One such event that was recorded was an impromptu sledding session down Carlton Hill, where one of the party ended up in the University infirmary shortly afterwards.

Sledding down Carlton Hill. An age-old saga.

Minute book illustrations.

And as a final note, there was an especially interesting aspect to these sorts of illustrations in the collection – the use of colour! Some of the volumes in particular felt like they’d been coloured in only yesterday – despite being at least three hundred years old. How they managed to keep it looking so pigmented is beyond me – and in any case, I’m sure it would be of interest to the art students.

This volume dates to 1771, if you can believe it!

We’ve got a little over a month of the project left, and I’m excited to see what we’ll discover in the Dk collection. One thing’s for sure – it’ll be incredibly interesting!