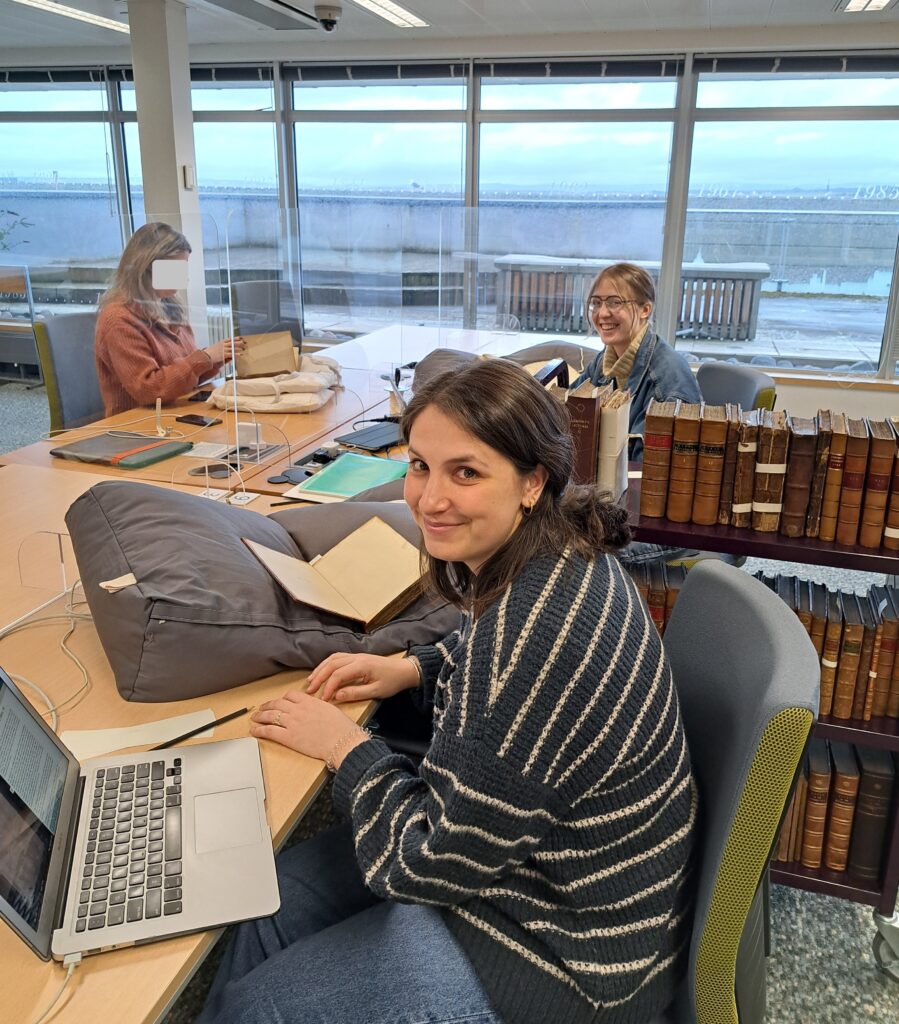

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art. I am fortunate to be one of two successful applicants for the position of Archival Provenance Intern with the Heritage Collections, University of Edinburgh. My own research considers early modern manuscript culture, translation and transcription, the materiality of text and image, collection histories, ideas of collaborative authorship, and the concept of self-design, explored through material culture methodologies. Throughout my PhD, I have visited many reading rooms, from the specialist collections rooms at the British Library and the Bodleian’s Weston Library, to the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge and the Warburg Institute. Working first-hand with historical material has been crucial to the development of my work, and I was eager to spend time ‘behind-the-scenes.’ This internship was attractive to me because of the more familiar aspects – like the reading room environment and object handling – but it also presented an opportunity to expand my understanding of manuscript production and book histories, develop my provenance and palaeography skills, and understand the function of archival cataloguing fields as finding aids through my own enhancement of metadata.

Madeleine (foreground) and Emily (background) in the reading room.

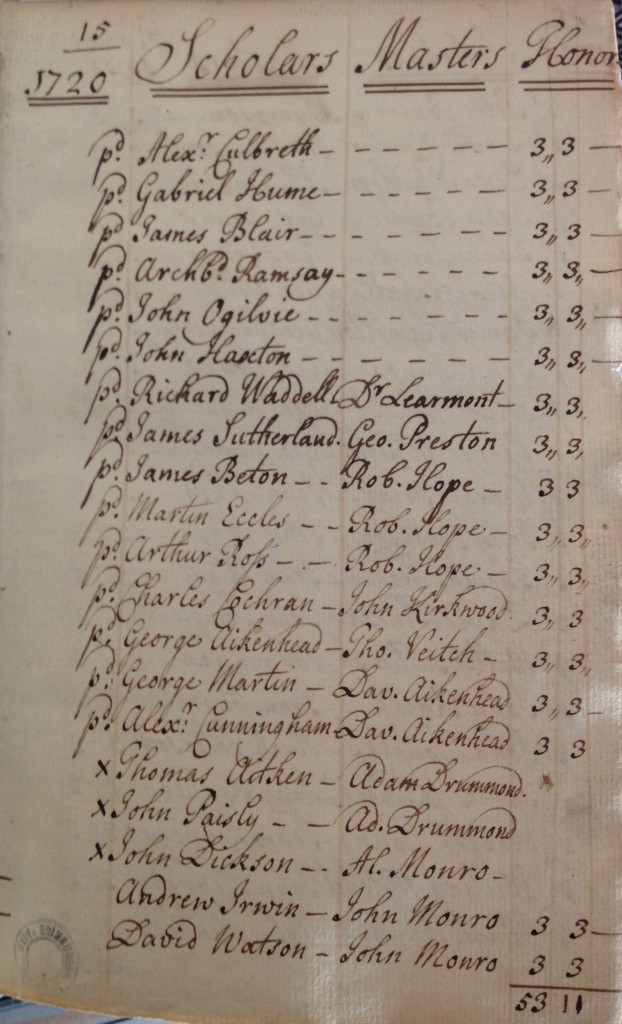

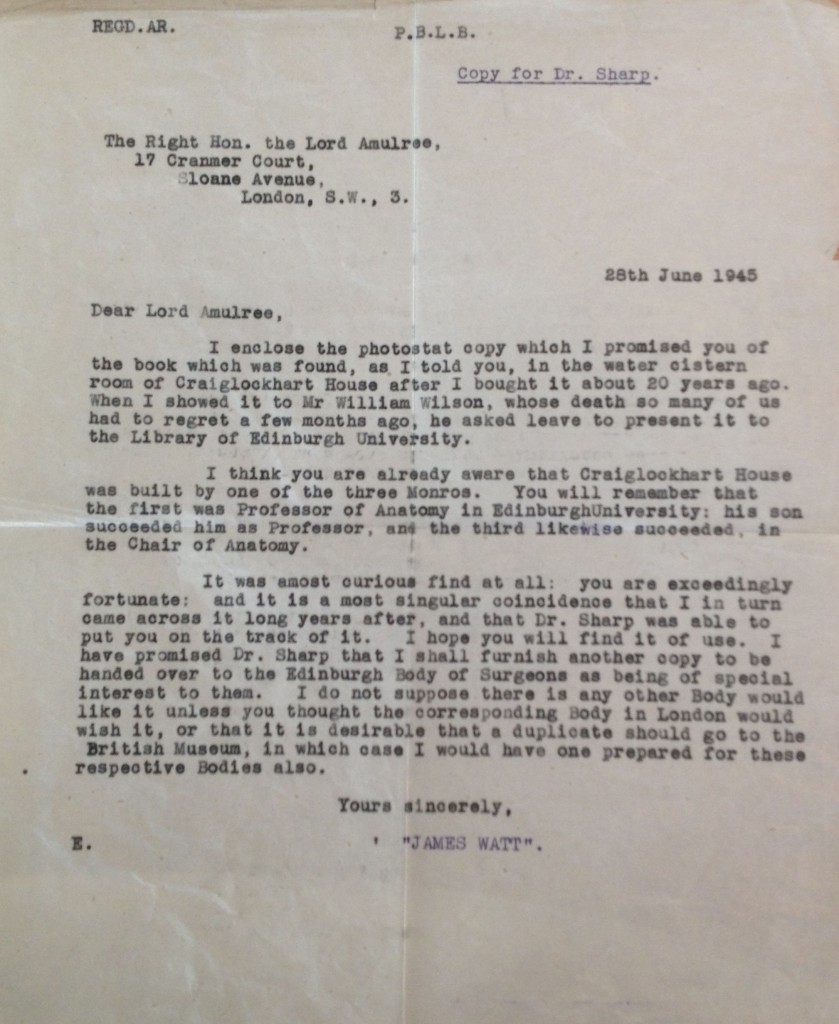

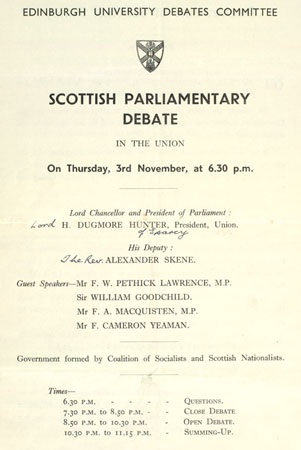

The aim of the project is to create a comprehensive resource list concerning the library’s oldest manuscripts, which contain material from the 16th– 20th centuries, in particular pre-20th century lecture notes, documents, and correspondence of or relating to university alumni and staff, as well as historical figures like Charles Darwin, Frédéric Chopin, and Mary Queen of Scots (to name a few). An old hand-list (dating from 1934 or before) was provided for the shelf-marks under consideration, and, using an Excel spreadsheet with pre-set archival fields, provenance research is being used to uncover details such as authorship/creator or previous ownership, how the volume came to be part the university’s collections, and extra-contextual information, like how the manuscript or its author/creator/owner is relevant to the university’s history.

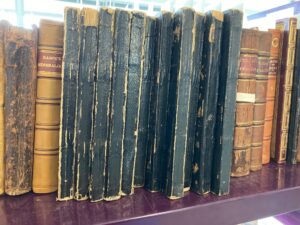

A collection of black notebooks containing transcribed lecture notes from 1881-1883. The lectures were given by various University staff on subjects such as natural philosophy, moral ethics, rhetoric, and English literature and were transcribed by different students.

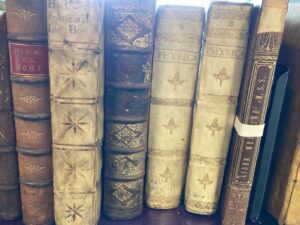

A great #shelfie featuring gold-tooling, banded spines, vellum bindings.

In addition to enhancing the biographical details of relevant actors in the history of the university, the research into this ‘collection’ of manuscripts provides a deeper understanding of the interests, priorities, and concerns – political, religious, intellectual, etcetera – of a particular society, or group, depending on the time period or place an individual object can be traced to. Inversely, thinking about what or who is not reflected in this subset of the archive is as informative as what material is present – unsurprisingly, a majority of this material is by men of a certain education and class. Though I would like to think of an archive as an impartial tool for historical research, I have to remind myself that decisions were made by certain individuals concerning what material was valuable or important (whatever that means!) to keep, or seek out, or preserve, and what might have been disregarded, or turned away.

While there is a growing list of what I, and my project partner, Emily, refer to as ‘Objects of Interest’ (read as: objects we could happily spend all day inspecting), there are some which stand out, either for their content – some concern historical events pertaining to the university or Scotland more generally – or their form.

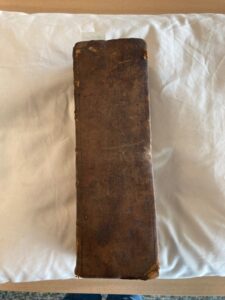

Dc.4.12 ‘Chronicle of Scotland’, front cover; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

Dc.4.12 ‘Chronicle of Scotland’, ‘Mar 24 1603’; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

This manuscript (above), ‘Chronicle of Scotland from 330 B.C. to 1722 A.D’, is notable for its slightly legible handwriting (a rarity) and its subject matter – the featured page recounts the death of Elizabeth I, James VI and I’s arrival in London, and later down the page, his crowning at Westminster. Mostly, its odd shape – narrow, yet chunky – is what was particularly eye catching. To quote an unnamed member of the research services staff: ‘Imagine getting whacked over the head with this thing!’

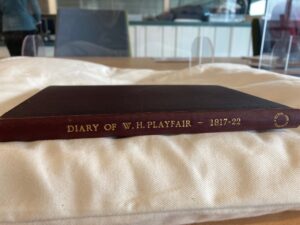

Of interest to the history of the university is this thin, red volume (below) containing an account written by William Playfair concerning the construction of some university buildings and the costs at this time (1817-1822). This page covers his outgoings – see his payment for the making of the ‘plaster models of Corinthian capitals for Eastern front of College Museum’ and his payment for the ‘Masonwork of Natural Histy Museum – College Buildings.’

Dc.3.73 Abstract of Journal of William Playfair, binding, cover; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

Dc.3.73 Abstract of Journal of William Playfair, expenditures; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

Of course, you cannot understand the scope of the history of the University of Edinburgh without considering its ‘battles’ – by this, I mean the ‘Wars of the Quadrangle’, otherwise known as the Edinburgh Snowball Riot of 1838, a two-day battle between Edinburgh students and local residents which was eventually ended by police intervention. This manuscript is a first-hand account from Robert Scot Skirving, one of the five students, of the 30 plus that were arrested, to be put on trial.

Dc.1.87 Account of the snowball riot; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

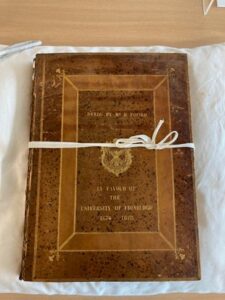

Finally, this object (below), from the first day of research is particularly fascinating – a box, disguised as a book, used to hold deeds granting the university with six bursaries for students of the humanities, from 1674-1678. The grantor is Hector Foord, a graduate of the university. The box is made from a brown, leather-bound book, that was once held shut with a metal clasp. The pages, cut into, are a marbled, swirling pattern of rich blue, red, green, and gold. The cover is stamped in gold lettering, with a gold embossed University library crest. There are delicate gold thistles pressed into the banded spine. Upon opening the manuscript, it contains two parchment deeds, and two vellum deeds, the latter of which are too stiff to open. You can see still Foord’s signature on one of them, and the parchment deeds are extremely specific about the requirements that must be met for a student to be granted money.

Dc.1.22 Deeds by Mr. H Foord, cover; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

Dc.1.22 Deeds by Mr. H Foord, inside of ‘box’ with all four deeds; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

The project has only just concluded its second month and we are lucky that it has been extended a month beyond the initial contract. Despite how much material we have covered so far, we are looking forward to discovering more interesting objects, and continuing to enhance our resource list. Stay tuned!