A LOST BUT RECONSTRUCTED HERITAGE… FROM THE LIBRARY OF SIR ROBERT STODART LORIMER (1864-1929), ARCHITECT

In the book collections curated by the CRC is the work entitled La Belgique monumentale: 100 planches en phototypie by Karel Sluyterman (1863-1931), the Dutch architect, designer and illustrator, and Jules Jacques van Ysendyck (1836-1901) the Belgian architect and propagandist for the neo-Flemish Renaissance style.

In the book collections curated by the CRC is the work entitled La Belgique monumentale: 100 planches en phototypie by Karel Sluyterman (1863-1931), the Dutch architect, designer and illustrator, and Jules Jacques van Ysendyck (1836-1901) the Belgian architect and propagandist for the neo-Flemish Renaissance style.

Title-page, ‘La Belgique monumentale’, by the architects Karel Sluyterman and Jules Jacques van Ysendyck, published by Martinus Nijhoff, 1915.

The work published in 1915 in the neutral Netherlands by Martinus Nijhoff – a prestigious publishing house in The Hague (La Haye) – contains dozens of collotype prints (a salts based photographic process) showing gems of Belgian architecture.

A foreword to the collection of prints states that: ‘As Belgium suffers the devastating horrors of war, it seemed appropriate to circulate images of some Belgian monuments already irreparably damaged and destroyed, and those which are threatened with destruction’.

A foreword to the collection of prints states that: ‘As Belgium suffers the devastating horrors of war, it seemed appropriate to circulate images of some Belgian monuments already irreparably damaged and destroyed, and those which are threatened with destruction’.

It goes on in very high-flown style: ‘In a very small space, Belgium offers an unparalleled accumulation of ancient cities and monuments, all standing witness to past greatness, offering the evidence of, and paying tribute to, the hard work always known in the country, and showing opulence in the worst distress’.

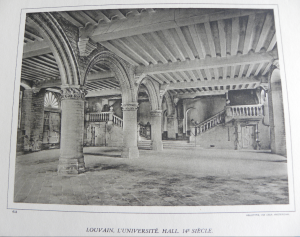

The plates listed include important buildings in the towns and cities of Aerschot (Aarschot), Anvers (Antwerpen), Courtrai (Kortrijk), Dinant, Dixmude (Diksmuide), Louvain (Leuven), Malines (Mechelen), Tournai (Doornik), and Ypres (Ieper).

Some of these towns and cities escaped major damage but others suffered catastrophic destruction inflicted by massive bombardment by both sides in the Great War.

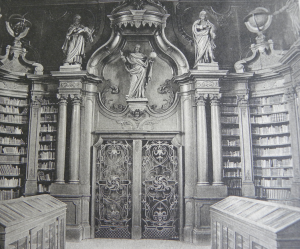

In 1914 the University in Louvain (Leuven) was destroyed. This was the 14th century University Library.

In Louvain, for example, on the 25 August 1914, the University Library was destroyed using petrol and incendiary devices. Some 230,000 volumes were lost in the destruction, including Gothic and Renaissance manuscripts, a collection of 750 medieval manuscripts, and more than 1,000 incunabula (books printed before 1501). The city lost one fifth of its buildings during the War.

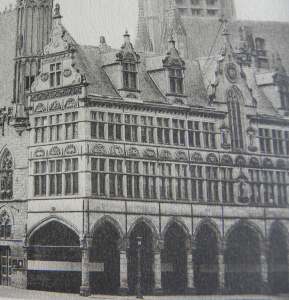

In Ypres too, massive destruction was suffered, with the 13th century Cloth Hall – Lakenhalle – being reduced to rubble.

The Cloth Hall (Lakenhalle) in Ypres (Ieper), Belgium, which during the course of the War was reduced to rubble. Reconstructed after the conflict, the original building was constructed between 1200 and 1304.

A label on the inside of the front cover of the portfolio of prints reads: ‘From the library of the late Sir Robert Lorimer. Presented by his Family February 1934’.

Lorimer was a prolific Scottish architect and furniture designer noted for his sensitive restorations of historic houses and castles, for new work in Scots Baronial and Gothic Revival styles, and for promotion of the Arts and Crafts movement.

This new addition to the Cloth Hall, called Nieuwerck, dated from the 17th century. This too was reconstructed during the 1920s.

La Belgique monumentale: 100 planches en phototypie can be accessed by contacting the CRC and quoting shelfmark: RECA.FF.116.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

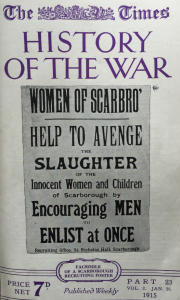

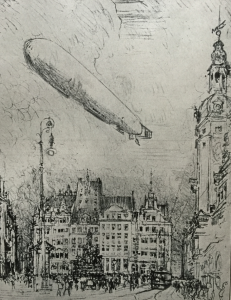

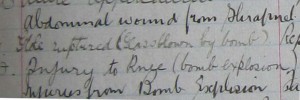

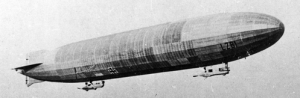

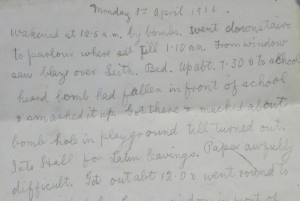

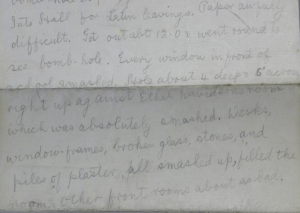

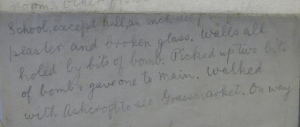

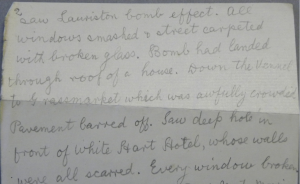

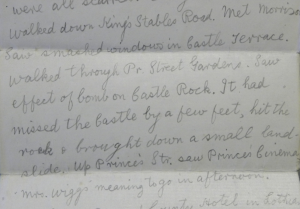

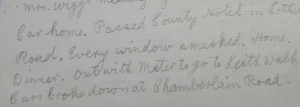

Nearly all of the damage had been caused by devices dropped from Zeppelin L14. Zeppelin L22 ventured only briefly into the city and just caused minor damage after jettisoning most of its bombs in fields near Berwick-upon-Tweed. Later in the year,

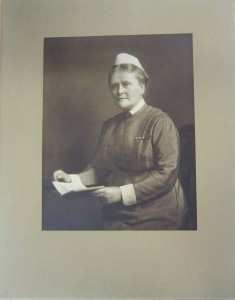

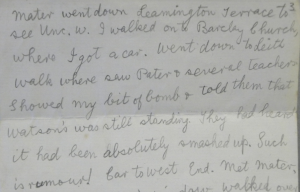

Nearly all of the damage had been caused by devices dropped from Zeppelin L14. Zeppelin L22 ventured only briefly into the city and just caused minor damage after jettisoning most of its bombs in fields near Berwick-upon-Tweed. Later in the year,  James Roland Rider was the son of a veterinary surgeon. He was born in Beamish, near Durham, in N.E.England, on 13 November 1894. He was educated at St. Bees, Cumbria, and at Newcastle Royal Grammar School.

James Roland Rider was the son of a veterinary surgeon. He was born in Beamish, near Durham, in N.E.England, on 13 November 1894. He was educated at St. Bees, Cumbria, and at Newcastle Royal Grammar School.