This week sees the hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Jutland, the largest and most important naval engagement of the First World War, and also a particularly Scottish event, as the majority of the British ships involved set out from Scottish ports – from Rosyth on the Forth, up to Scapa Flow in Orkney.

As the Navy, the politicians and VIPs, heavy security and the media descend on Orkney this week, it seemed an appropriate moment to see what we could find in our collections of the contemporary reporting and commentary on the battle.

The outcome of the battle of Jutland was complex: the losses of British ships and lives were far higher than the Germans’; but, it was a tactical advantage in that Britain retained control of the seas, maintained the blockade of German shipping and ultimately it contributed to winning the war. However, immediately after the battle the longer-term consequences were not obvious and the consequences of the confused action were very much open to interpretation.

Jutland, was, for the Admiralty, a media disaster: the German High Seas Fleet, having retreated to port, issued prompt communiques declaring it their victory. The Admiralty was unable to report so rapidly; the British fleet was still at sea, and they had no information. When they did issue their own communique it was so badly worded as to make the British media interpret it as a defeat.

This was embarrassing. The situation inspired the Admiralty to start a systematic propaganda campaign, as well as a review of how they handled these matters.

Their propagandist of choice was Rudyard Kipling – famous, influential, very much in support of the war, but long sympathetic to the lot of the ordinary soldier or sailor. He was already writing general newspaper articles for the Admiralty – three were ready for publication when Jutland happened, appearing in The Times in late June 1916. Kipling’s visits to the Fleet in connection with these had made contacts among the officers, and he had heard first-hand accounts of the battle as soon as a week after it happened. In August he was provided with all the official reports, and in October four articles were published in The Daily Telegraph.

These begin by outlining a positive interpretation of the battle, stressing the confusion of the action and the difficulty for those involved of being sure what was happening. The rest of the articles, consistently upbeat in tone, consist of anecdotes showing the bravery, resourcefulness and ingenuity of the men involved, in overcoming battle damage, hitting their enemy targets, and getting their ships home. They owe as much to Kipling’s contacts among the ships’ crews as to the official reports, and are as colourful in the telling as his fictional stories. Indeed, they are openly somewhat fictionalised to avoid disclosing military intelligence.

From a modern perspective the thing which seems odd about these is the timing. In our modern instant-news culture a series of lengthy articles would be unlikely to be published four and a half months after the event, and certainly not as a means to win round public opinion in that way. What is even more alien to modern media culture, is that these, along with Kipling’s other articles for the Admiralty, were republished in book form before the end of 1916.

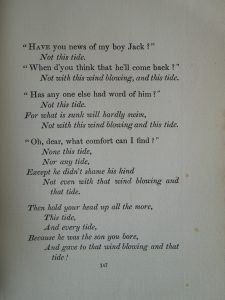

However, the book version interspersed the articles with verse, and acquired a greater nuance of interpretation than that conveyed by the original articles alone. The Jutland section of the book opens with ‘My Boy Jack’, a reflection on the dead. This undoubtedly carries some of Kipling’s feelings about the loss of his own son at the battle of Loos the previous year, framed in naval terms.

Our copy of Sea Warfare, can be consulted in the Centre for Research Reading Room, shelfmark: S.B. 82391 Kip.