GEORGE MCDONALD SUTHERLAND AND HIS LOST ‘YEARS TO BE’… THE STORY OF A ROBBED CAREER.

George McDonald Sutherland, from a photograph loeaned and reproduced with the kind permission of his great-niece.

In his 1914 sonnets (III. The Dead), the war poet Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) wrote of the fallen, the dead, as having given up

‘…the years to be… Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene… That men call age…’.

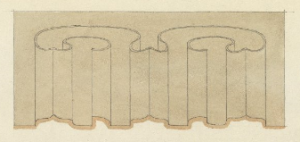

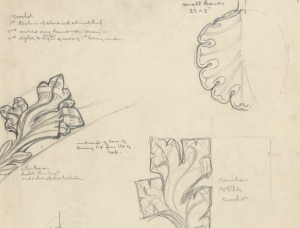

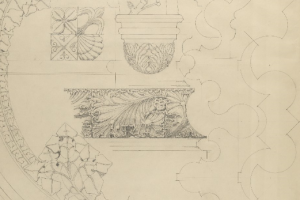

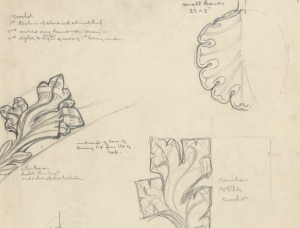

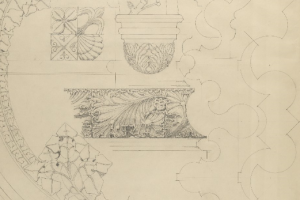

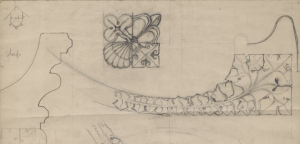

Architectural mouldings drawn by George McDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

Brooke’s words make us think about the working lives and the achievements, and possible greatness that the dead of the First World War – and other wars – would never reach or know. They ‘had seen movement and heard music, known slumber and waking […] Felt the quick stir of wonder […] touched flowers and furs and cheeks’ (Brooke 1914 sonnets. IV. The Dead). They had begun their careers and to make their mark on the world, and, continuing with the Brooke theme – but thinking about the story of George McDonald Sutherland told below – they had smelt sharpened wood pencil, and felt cold, raw mason’s stone.

George McDonald Sutherland (right) with his brothers David (left) and Norman (middle). From a photograph loaned and reproduced with the kind permission of their great-niece.

George McDonald Sutherland was born in 1886, the son of George P. Sutherland and Helen Sutherland of Galashiels in Selkirkshire. His father, who served as an apprentice sculptor in Edinburgh, London and New York, went on to found the firm of George Sutherland & Sons (Galashiels), Sculptors and Monumental Masons, in 1881. The firm operated throughout the Borders, and the carvings on the local Galashiels Post Office building were created by the elder Sutherland in 1886, the year of his son’s birth.

Detail from an oak bench drawn by George McDonald Sutherland in July 1904, during his apprenticeship. Coll-1319.

Detail from an oak bench drawn by George McDonald Sutherland in July 1904, during his apprenticeship. Coll-1319.

At the age of seventeen, in 1903, following in his father’s footsteps, the younger George McDonald Sutherland was apprenticed to the architectural practice of Robert Lorimer (1864-1929), later Sir Robert Lorimer, of Edinburgh. After his apprenticeship and after he had become an architect himself, George McDonald Sutherland went to Toronto, Canada, to start an architectural business and bought land there too.

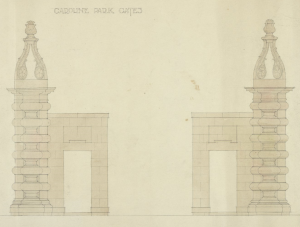

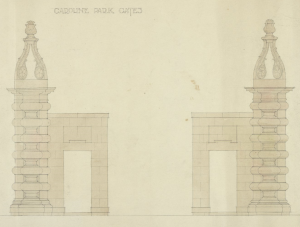

Caroline Park gates, Granton, Edinburgh, drawn by George McDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

On the outbreak of war in 1914, George McDonald Sutherland wanted to come back to Scotland and fight, although the family tried to dissuade him. Nevertheless he did return – like many other Scottish Canadians – and joined the 4th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers and Lothians and Borders Horse.

George McDonald Sutherland in uniform. Photograph reproduced with the kind permission of his great-niece.

George McDonald Sutherland in uniform. Photograph reproduced with the kind permission of his great-niece.

At the age of 31, 2nd Lieutenant George McDonald Sutherland, by then of the 7th/8th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, was killed at Arras, France, on 9 April 1917 at the start of the opening phase of the British-led Battle of Arras (also known as the Second Battle of Arras), of which the Battle of Vimy Ridge formed a part.

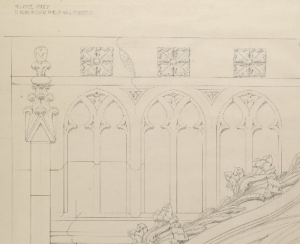

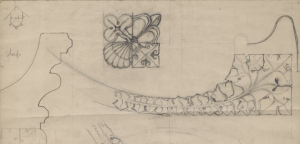

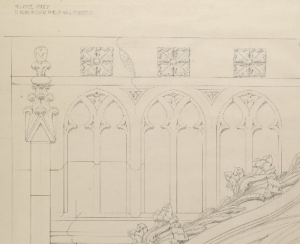

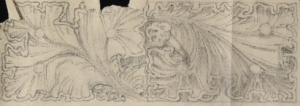

Architectural detail from Melrose Abbey, drawn by George MacDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

From 9 April, the day of George’s death, until 16 May 1917, British, Canadian, South African, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and Australian troops attacked German defences near this French city on the Western Front. While there were major gains on the first day – when George was killed – these were followed by stalemate. The battle cost nearly 160,000 British casualties and about 125,000 German casualties.

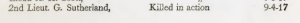

George McDonald Sutherland noted in the Roll-of-Honour in the work ‘War record of 4th Bn. King’s Own Scottish Borderers and Lothian and Border Horse : with history of the T.F. Associations of the counties of Roxburgh, Berwick and Selkirk’, published in 1920. Edinburgh University Library general collections. D546.5.4th War. (2nd Floor).

George was buried in Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery, at Souchez, in the Pas de Calais department of northern France, about 3.5 kilometres north of Arras – a cemetery maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWCG).

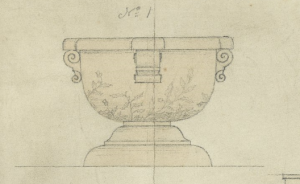

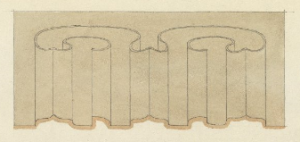

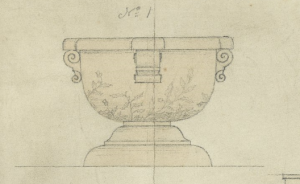

From a drawing of urns done by George McDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

Drawing of urns done by George McDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319

Back home in Galashiels, in the Borders, the family firm of Sculptors and Monumental Masons continued to operate over several decades, with war memorials and grave stones comprising a large part of the business, and with George’s brother Norman running the Hawick office of the firm.

Architectural mouldings drawn by George McDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

Indeed, the carved ‘Angel of Peace’ on the Galashiels war memorial at the Burgh Chambers – unveiled by Field-Marshal Earl Haig in 1925 – was the work of another of George’s brothers, sculptor David Sutherland (1884-1962), who saw military service in Salonika, Batumi and Baku.

Architectural mouldings drawn by George McDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

Because the ‘Angel’ on the Galashiels memorial had been carved leaning slightly forward and with its head dipped, light shining from the side creates shadows giving the effect of Angel’s wings above the statue (though, regrettably, modern street-lighting obscures the effect).

Architectural mouldings drawn by George McDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

It seems fitting though that George McDonald Sutherland’s name is inscribed on the Roll of Honour in Galashiels displaying an Angel carved by his brother on the Burgh Chambers designed by the very architect who trained him – Sir Robert Lorimer.

Architectural mouldings drawn by George McDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

George Sutherland & Son of Galashiels purchased a Tweedmouth monumental mason’s yard which was to have been run by a younger member of the Sutherland family. However, before he could take over the yard, Lt. John McDonald Sutherland (Cameron Highlanders), a signaller, was killed on 28 March 1945 during the push over the River Rhine.

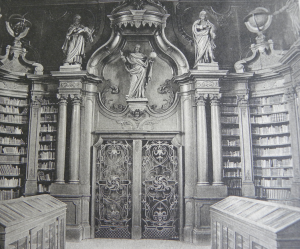

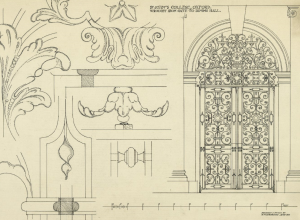

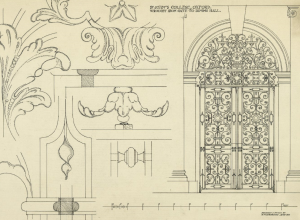

The wrought-iron gates to dining hall at St. John’s College, Oxford, drawn by George McDonald Sutherland in 1910. Coll-1319.

Although his ‘years to be of work and joy’ were stolen from him and we could never see the mature product of his working life, in 2011 a collection of original architect’s drawings by George McDonald Sutherland was kindly donated to Edinburgh University Library, Centre for Research Collections, by a great-niece living in Surrey, England. These allow us to see the talent of his early years in architecture. Parts of these drawings illustrate this blog-post honouring George McDonald Sutherland (1886-1917). Younger members of the family of George McDonald Sutherland’s great-niece are on their way to following career paths in architecture too.

Architectural detail from Melrose Abbey, drawn by George MacDonald Sutherland. Coll-1319.

But… back to Brooke and to the 1914 sonnet IV. The Dead… and to the life, career and ambitions of George McDonald Sutherland… the dead of the First World War and other wars…

‘All this is ended […] And after, Frost, with a gesture, stays the waves that dance ‘.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

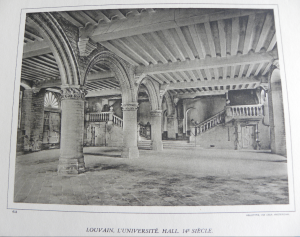

In the book collections curated by the CRC is the work entitled La Belgique monumentale: 100 planches en phototypie by Karel Sluyterman (1863-1931), the Dutch architect, designer and illustrator, and Jules Jacques van Ysendyck (1836-1901) the Belgian architect and propagandist for the neo-Flemish Renaissance style.

In the book collections curated by the CRC is the work entitled La Belgique monumentale: 100 planches en phototypie by Karel Sluyterman (1863-1931), the Dutch architect, designer and illustrator, and Jules Jacques van Ysendyck (1836-1901) the Belgian architect and propagandist for the neo-Flemish Renaissance style.

A foreword to the collection of prints states that: ‘As Belgium suffers the devastating horrors of war, it seemed appropriate to circulate images of some Belgian monuments already irreparably damaged and destroyed, and those which are threatened with destruction’.

A foreword to the collection of prints states that: ‘As Belgium suffers the devastating horrors of war, it seemed appropriate to circulate images of some Belgian monuments already irreparably damaged and destroyed, and those which are threatened with destruction’.