‘…THIS PUCE-COLOURED COCKLESHELL […] HAS TO SPRING UP AGAIN WITH NEW QUESTIONS AND BEAUTIES WHEN EUROPE HAS DISPOSED OF ITS DIFFICULTIES…’

Detail from the ‘puce-coloured’ front cover of ‘Blast’, issue 2, July 1915, in the A.H. Campbell Collection.

These were the words of Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957), editor of Blast, in his editorial piece published in the July 1915 issue (only the second issue) of the journal. About that issue, he said that it ‘finds itself surrounded by a multitude of other Blasts of all sizes and descriptions’.

Detail from the front cover of ‘Blast’, showing month of publication of issue 2… being July 1915… in the A.H. Campbell Collection.

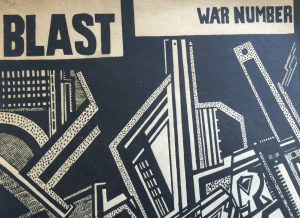

Blast was the literary magazine of the Vorticist movement in Britain and it only survived two issues. The first issue came out only weeks before the beginning of the War, and the second came out a year later in 1915. It featured a woodcut by Lewis on the cover.

Detail from the front cover of ‘Blast’, issue 2, a woodcut by Wyndham Lewis, in the A.H. Campbell Collection.

The vorticists were an avant-garde group formed in London in 1914 – with Wyndham Lewis as its founder – aiming towards an art that expressed the dynamism of the modern world. Vorticism was launched with the journal Blast which, within its content included manifestos ‘blasting’ the effeteness of British art and culture and proclaiming the vorticist aesthetic.

Detail from the title page of ‘Blast’ issue 2, July 1915, in the A.H.Campbell Collection.

Vorticist painting combined Cubist fragmentation of reality with an imagery derived from the machine and the urban environment. In its embrace of dynamism, the machine age and all things modern, it is more closely related to Futurism.

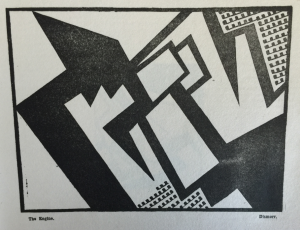

‘The Engine’ by one of the signatories to the Vorticist manifesto Jessica Dismorr (1885-1939). Her illustrations show a sharing of the involvement with the dynamism of the machine-age city. In ‘Blast’, issue 2, July 1915, in the A. H. Campbell Collection.

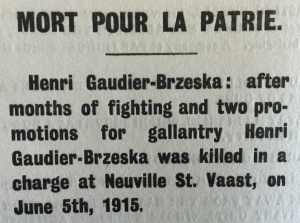

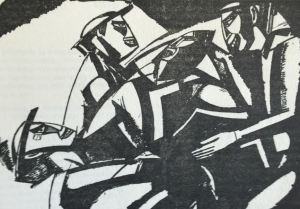

Blast, issue 2, included designs by painter and illustrator Jessica Dismorr (1885-1939), artist and architect Frederick Etchells (1886-1973), artist and sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915), painter Jacob Kramer (1892-1962), and by figure and landscape painter, etcher and lithographer, Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889-1946).

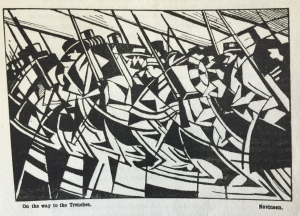

‘On the way to the trenches’ by Nevinson, in ‘Blast’ issue 2, July 1915, in the A. H. Campbell Collection.

It also contained graphic contributions from the figure and portrait painter William Roberts (1895-1980), Helen Saunders [or Sanders] (1885-1963), Dorothy Shakespear (1886-1973) artist and wife of Ezra Pound, artist Edward Alexander Wadsworth (1889-1949), and also Wyndham Lewis.

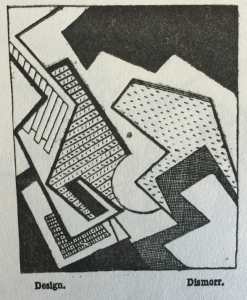

‘The Design’ by Jessica Dismorr (1885-1939), in ‘Blast’, issue 2, July 1915, in the A. H. Campbell Collection.

Other contributions were made by Ezra Pound (1885-1972), Ford Madox Hueffer [Ford Madox Ford] (1873-1939), and T. S. Eliot (1888-1965).

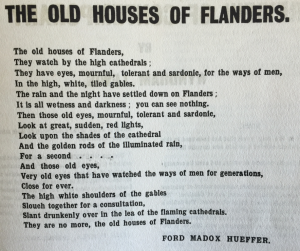

The poem, ‘The old houses of Flanders’ by Ford Madox Hueffer (Ford Madox Ford) in ‘Blast’, issue 2, July 1915, p.37, in the A. H. Campbell Collection.

It had been the unfolding human drama, the unimagined industrial scale of death borne out of the machine-age, and the absolute disaster of the War – known to that generation as the Great War – that came to drain the Vorticists of their creative zeal. The real war experience of Ford Madox Ford influenced his poem ‘The old houses of Flanders’.

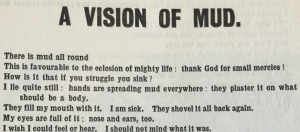

The poem, ‘A vision of mud’ by Helen Saunders in ‘Blast’, issue 2, July 1915, pp.73-74, in the A. H. Campbell Collection.

Ford writes of the mournful eyes of the houses watching the ways of men, and of the rain and night settled down on Flanders; how the eyes look at great, sudden red lights and the golden rods of the illuminated rain; how the old eyes that have watched the ways of men for generations close for ever, and how the gables slant drunkenly over.

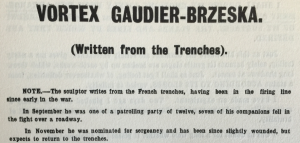

‘Vortex Gaudier-Brzeska (Written from the trenches’, in ‘Blast, issue 2, July 1915, pp.33-34, in the A. H. Campbell Collection.

Unlike Ford, Helen Saunders had no first-hand knowledge of the trenches and the shell blasted Flanders but in her poem ‘A vision of mud’ she took the image of the mud of the trenches to describe a wider sense of foreboding and anxiety. She imagined what would happen to a body underground and about what it would feel like to drown in mud with eyes, nose, mouth and ears filled with it. She imagined the distortion of awareness, and how the body would swell and grow as it filled with mud. She described a muddy soup of bodies.

‘…There is mud all round […]

They fill my mouth with it. I am sick. They shovel it back again.

My eyes are full of it […]

It is pouring into me so that my body swells and grows heavier every minute […]

I have just discovered with what I think is disgust, that there are hundreds of other bodies bobbing about against me.

They also tap me underneath…’

Artwork in ‘Blast’, issue 2, July 1915, p.49, in A. H. Campbell Collection.

The trenches were also described by Frenchman Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. He wrote:

Human masses teem and move, are destroyed and crop up again.

Horses are worn out in three weeks, die by the roadside.

Dogs wander, are destroyed, and others come along.

It had been Lewis’s hope that with the end of the War – when Europe had ‘disposed of its difficulties’ – Blast and the Vorticist movement would ‘spring up again with new questions’ in order to tackle the ‘serious mission’ that it would have ‘on the other side of World-War’.

‘Design for programme cover – Kermesse’, by Wyndham Lewis, in ‘Blast’ issue 2, July 1915, p.75, in the A. H. Campbell Collection.

The War brought Vorticism to an end for the reasons already described in paragraphs above, but in 1920 Lewis did make a brief attempt to revive it with ‘Group X’, a short lived group of British artists formed to provide a continuing focus for avant-garde art in Britain.

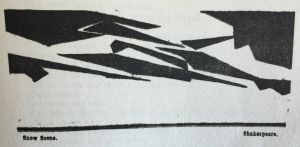

‘Snow-scene’ by Dorothy Shakespear, in ‘Blast’ issue 2, July 1915, p.35, in A. H. Campbell Collection.

The real stories, real imagery, and real maimed victims of War – the horrors of War – had brought about a rejection of the avant-garde in favour of traditional art, and there was a ‘return to order’ and the more traditional approaches to art creation.

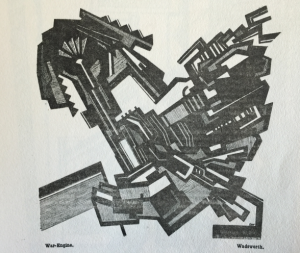

‘War-engine’ by Wadsworth, in ‘Blast’, issue 2, July 1915, in A. H. Campbell Collection.

Nevertheless, the typography of the Vorticists possibly places them as important forerunners of the revolution in graphic design that occurred in the 1920s and 1930s.

A copy of Blast, Issue 2, July 1915, was re-discovered in the Papers of Archibald H. Campbell, a collection which had been undergoing preliminary listing.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections, Edinburgh University Library

Used in the construction of this blog-post, in addition to the issue of Blast (2) 1915, were: (1) ‘ Beyond the trenches’, Dr. Kate McLoughlin, in Research & teaching, Review 2013, pp.30-31, from Birkbeck web-pages [accessed 27 July 2016]; and, (2) ‘Vorticism’ and other pages on the website of the tate.org.uk [accessed 27 July 2016].