Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

March 2, 2026

Women and the politics of care in zoo, animal advocacy and veterinary archival records, 1910-1930

LONDON, UK – 4 DECEMBER 2018: A statue of the English suffragist and union leader Millicent Fawcett, an early feminist campaigner for women’s suffrage (Photo: Shutterstock).

Welcome to this series on research for the One Health archival project!

This week, I will present a bit about my current research project with Dr. Alette Willis, Chancellor’s Fellow and Senior Lecturer in the School of Health in Social Science. We have been looking at the roles of women in care practices in the early twentieth century, through evidence we find across OneKind (SSPV), the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) and the Royal (Dick) Veterinary College archival materials. I’ll provide a quick glimpse into what we’ve found so far regarding women’s caring roles during the time period of 1910-1930 in the three organisations.

OneKind (SSPV): women as moral compass and source of compassion

Some women involved in women’s suffrage in the UK in the early twentieth century also became anti-vivisectionists. We found that women were central to the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Vivisection (SSPV), and many also proved active in other social movements. Women in the UK experienced the threat of government-sanctioned and medically applied control over their bodies after the passing of the Contagious Disease Act 1866 (see this article on the Victorian Web for an overview). Women, then, could identify with the suffering of animals whose bodies were controlled completely during acts of vivisection.

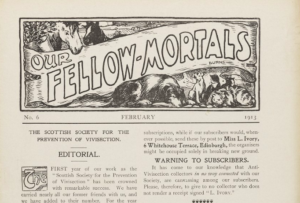

Image of Our Fellow Mortals Magazine, volume number 6, February 1913, SSPV

But, the brutality of vivisection was also railed against as corrupting good souls, and women in the SSPV expressed a neo-romanticism that rejected material and impassionate science, apparent in their magazine, Our Fellow Mortals, with volumes published from 1911 to 1925; my previous research of cultural attitudes towards animals in France showed a similar perception in the 19th century of the corrupting power of witnessing or participating in acts of brutality or cruelty towards animals. Examples can be found in the SSPV magazine of women characterised, and characterising themselves, as the moral compass of society, the source of compassion. For instance, the SSPV included a quote from poet George Barlow’s essay, ‘Science and Sympathy’, in volume number 6 of the magazine, February 1913, page 7:

‘More and more, for good or evil, women are beginning to study physiology and to take active part in medical practice … We must remember that the feminine faculty of tenderness is the saving factor in the coarse and selfish world. If we teach women to be cruel, our folly will re-act upon ourselves in unforeseen and terrible ways … No amount of scientific knowledge, no fabulous increase of material comforts or luxuries, would ever compensate mankind for the loss of its one most priceless faculty, the gift of loving-tenderness’ (1618/1/4/2/1)

Thus, women who entered medicine or veterinary medicine, could lose their feminine compassion. This perception of women also laid the burden of caring about and for other animals at their feet; women should care deeply about the fate of animals used in vivisection, as well as animals killed for food and other goods. This positioning of women is apparent in flyers held by the SSPV from the Council of Justice to Animals, in this case an appeal to women regarding humane slaughtering, by the Secretary of the Council, Violet Woods, most likely dated in the early to mid 1920s:

‘It is to the women of this country that we must appeal to bring about this reform. Will they fail to realise their responsibility? The fate of thirty million animals slaughtered every year in these isles is in their hands, and humanity cries aloud to them to do their duty. Another year may prove whether it may be proclaimed to foreign lands that every animal in Britain has a painless death, because the women realised their sufferings, realised their own responsibility, exercised their power, and have done their duty.’ (1618/2/3/2/2)

Women within the SSPV cared about animals but were not necessarily ‘on the ground’ caring for, and they represented the upper classes.

Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS): unpaid labour and generosity

Red Pandas at Edinburgh Zoo (Photo: Elizabeth Vander Meer, 2024)

Women appear in the RZSS archival records in terms of caring for animals, and plants, in the form of unpaid labour, undertaking keeper work and gardening on zoo grounds. Unpaid labour defines women’s involvement in care practices at Edinburgh Zoo in the early twentieth century, with wives of keepers, architects and garden designers fulfilling these roles alongside their husbands; this was the case for zoo founder, Thomas Gillespie, whose wife, Mary Elizabeth, supported many aspects of zoo animal care and management. Women also cared about animals and the establishment through monetary, food and animal donations. Women who donated money or food could be characterised as inhabiting higher socio-economic strata in Edinburgh, evident in RZSS Annual Reports for the period. Several women appear in paid work as refreshment manageresses, as described in the RZSS Annual Reports.

We can find what could be considered an anthroporphising of animals in the case of descriptions of mothers and mothering found in the RZSS Annual Reports. This example is useful to consider here, from the 1930 Annual Report, page 12:

‘For the first time in the history of the Park a litter of three polar bear cubs was born, but “Sheila” did not prove a good mother, and devoured them as soon as they were born’

Polar bears, usually males, eat cubs when resources are scarce in wild conditions, but females are protective of young (National Geographic has shared footage of a male polar bear killing and eating a cub, February 2016); in this case, the zoo context at the time could be considered carefully to understand what triggered cannibalistic behaviour in the female.

Royal (Dick) Veterinary College: the absence of women

Women are conspicuously absent from the veterinary archival materials, due to the late allowance of women into the College, by 1948. But Alette and I are approaching the archive in terms of this absence and the presence of men who are caring for animals. This research is work in progress, so I will share more if I can in a later blog post!

Skene, Societies and Swedish Serendipity

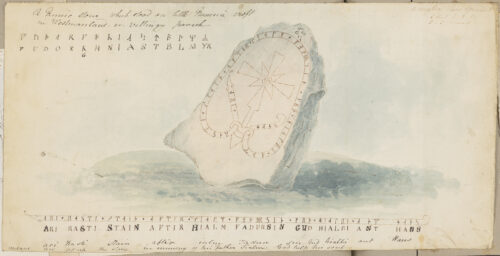

How often do you walk past a 1000 year old rune stone? The answer is every day, if you work or study near the Main Library!

Earlier this year I completed a project photographing James Skene’s Album of Sketches in greater detail. When I came across his runestone illustration again I was intrigued and did some research, making the surreal discovery that the subject was a 3 minute walk away. At 50 George Square behind the Scandinavian Studies Department, stands a Swedish runestone with a curious history. This 1.3 tonne granite stone found its new home here at the university in 2019, having been moved several times prior.

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art. I am fortunate to be one of two successful applicants for the position of Archival Provenance Intern with the Heritage Collections, University of Edinburgh. My own research considers early modern manuscript culture, translation and transcription, the materiality of text and image, collection histories, ideas of collaborative authorship, and the concept of self-design, explored through material culture methodologies. Throughout my PhD, I have visited many reading rooms, from the specialist collections rooms at the British Library and the Bodleian’s Weston Library, to the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge and the Warburg Institute. Working first-hand with historical material has been crucial to the development of my work, and I was eager to spend time ‘behind-the-scenes.’ This internship was attractive to me because of the more familiar aspects – like the reading room environment and object handling – but it also presented an opportunity to expand my understanding of manuscript production and book histories, develop my provenance and palaeography skills, and understand the function of archival cataloguing fields as finding aids through my own enhancement of metadata.

Madeleine (foreground) and Emily (background) in the Reading Room.

The aim of the project is to create a comprehensive resource list concerning the library’s oldest manuscripts, which contain material from the 16th– 20th centuries, in particular pre-20th century lecture notes, documents, and correspondence of or relating to university alumni and staff, as well as historical figures like Charles Darwin, Frédéric Chopin, and Mary Queen of Scots (to name a few). An old hand-list (dating from 1934 or before) was provided for the shelf-marks under consideration, and, using an Excel spreadsheet with pre-set archival fields, provenance research is being used to uncover details such as authorship/creator or previous ownership, how the volume came to be part the university’s collections, and extra-contextual information, like how the manuscript or its author/creator/owner is relevant to the university’s history.

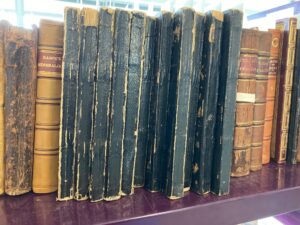

A collection of black notebooks containing transcribed lecture notes from 1881-1883. The lectures were given by various University staff on subjects such as natural philosophy, moral ethics, rhetoric, and English literature and were transcribed by different students.

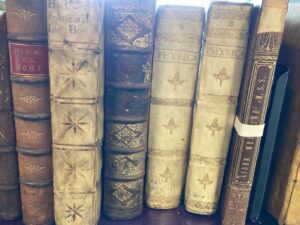

A great #shelfie featuring gold-tooling, banded spines, vellum bindings.

In addition to enhancing the biographical details of relevant actors in the history of the university, the research into this ‘collection’ of manuscripts provides a deeper understanding of the interests, priorities, and concerns – political, religious, intellectual, etcetera – of a particular society, or group, depending on the time period or place an individual object can be traced to. Inversely, thinking about what or who is not reflected in this subset of the archive is as informative as what material is present – unsurprisingly, a majority of this material is by men of a certain education and class. Though I would like to think of an archive as an impartial tool for historical research, I have to remind myself that decisions were made by certain individuals concerning what material was valuable or important (whatever that means!) to keep, or seek out, or preserve, and what might have been disregarded, or turned away.

While there is a growing list of what I, and my project partner, Emily, refer to as ‘Objects of Interest’ (read as: objects we could happily spend all day inspecting), there are some which stand out, either for their content – some concern historical events pertaining to the university or Scotland more generally – or their form.

Dc.4.12 ‘Chronicle of Scotland’, front cover; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

Dc.4.12 ‘Chronicle of Scotland’, ‘Mar 24 1603’; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

This manuscript (above), ‘Chronicle of Scotland from 330 B.C. to 1722 A.D’, is notable for its slightly legible handwriting (a rarity) and its subject matter – the featured page recounts the death of Elizabeth I, James VI and I’s arrival in London, and later down the page, his crowning at Westminster. Mostly, its odd shape – narrow, yet chunky – is what was particularly eye catching. To quote an unnamed member of the research services staff: ‘Imagine getting whacked over the head with this thing!’

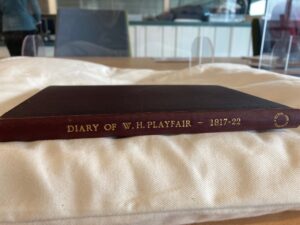

Of interest to the history of the university is this thin, red volume (below) containing an account written by William Playfair concerning the construction of some university buildings and the costs at this time (1817-1822). This page covers his outgoings – see his payment for the making of the ‘plaster models of Corinthian capitals for Eastern front of College Museum’ and his payment for the ‘Masonwork of Natural Histy Museum – College Buildings.’

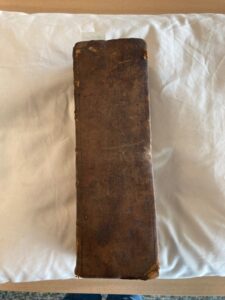

Dc.3.73 Abstract of Journal of William Playfair, binding, cover; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

Dc.3.73 Abstract of Journal of William Playfair, expenditures; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

Of course, you cannot understand the scope of the history of the University of Edinburgh without considering its ‘battles’ – by this, I mean the ‘Wars of the Quadrangle’, otherwise known as the Edinburgh Snowball Riot of 1838, a two-day battle between Edinburgh students and local residents which was eventually ended by police intervention. This manuscript is a first-hand account from Robert Scot Skirving, one of the five students, of the 30 plus that were arrested, to be put on trial.

Dc.1.87 Account of the snowball riot; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

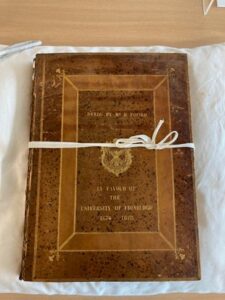

Finally, this object (below), from the first day of research is particularly fascinating – a box, disguised as a book, used to hold deeds granting the university with six bursaries for students of the humanities, from 1674-1678. The grantor is Hector Foord, a graduate of the university. The box is made from a brown, leather-bound book, that was once held shut with a metal clasp. The pages, cut into, are a marbled, swirling pattern of rich blue, red, green, and gold. The cover is stamped in gold lettering, with a gold embossed University library crest. There are delicate gold thistles pressed into the banded spine. Upon opening the manuscript, it contains two parchment deeds, and two vellum deeds, the latter of which are too stiff to open. You can see still Foord’s signature on one of them, and the parchment deeds are extremely specific about the requirements that must be met for a student to be granted money.

Dc.1.22 Deeds by Mr. H Foord, cover; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

Dc.1.22 Deeds by Mr. H Foord, inside of ‘box’ with all four deeds; Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

The project has only just concluded its second month and we are lucky that it has been extended a month beyond the initial contract. Despite how much material we have covered so far, we are looking forward to discovering more interesting objects, and continuing to enhance our resource list. Stay tuned!

New to the Library: Archive of Celtic-Latin Literature and Monumenta Germaniae Historica

I’m happy to let you know that after a successful trial last year the Library now has access to 2 Brepolis databases: Monumenta Germaniae Historica and Archive of Celtic-Latin Literature.

These can both be accessed from the Databases A-Z list and DiscoverEd.

Monumenta Germaniae Historica (eMGH)

On trial: Vanity Fair Archive

*The Library has purchased the Vanity Fair Magazine Archive and this can be accessed via Newspapers, Magazines and Other News Sources or the Databases A-Z*

Thanks to a request from a HCA student the Library currently has trial access to the Vanity Fair Magazine Archive from EBSCO, which presents an extensive collection of the popular magazine in a comprehensive cover-to-cover format, dating from its very first issue in 1913.

You can access Vanity Fair Magazine Archive via the E-resources trials page.

Trial access ends 3rd May 2024. Read More

Archival Research on Bacterial Infections, Part 2: Responses to TB in Dick Vet, RZSS and OneKind Archival Records

Now for the next part in this series on bacterial infections, sharing some findings from archival research!

The Dick Vet, RZSS and OneKind, or SSPV (Scottish Society for the Prevention of Vivisection), each related animal health and welfare to human health, but in somewhat different ways. All three organisations acknowledged the conditions that could lead to zoonotic disease transmission and outbreaks of disease such as TB; they noted poor welfare conditions reducing animals’ resistance, and poor health in the case of humans (diet, etc), along with crowded and unhygienic conditions. But they presented different perspectives in the early to mid-twentieth century on how to tackle public health issues of bacterial infections, based on different understandings of animal welfare and cruelty.

ArchivesSpace – where you’ll find archival records for the Royal (Dick) Veterinary College

The Dick Vet attended to animal health often in the service of human health, especially in the case of animals in agriculture, their main practice in the mid 19th to early 20th centuries prior to the burgeoning of companion animal ownership. The Dick Vet contributed to the Scottish Branch of the National Veterinary Medicine Association (NVMA) and its scheme for the Eradication of Bovine TB, which recognised that stress in cows reduced resistance to disease:

‘It may also be said that the body economy of the individual cows moved from market to market soon after calving is often so upset that resistance to new infection or infection already established is greatly reduced. The spread of the disease is encouraged in this way’. (Scottish Branch of NVMA 1933)

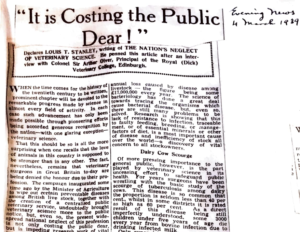

While treating individuals, the veterinary focus remained on a wider good, of populations of humans and animals. This approach allowed the sacrifice of individuals to vivisection, or animal experimentation, in order to advance understandings of diseases and treatments. The Dick Vet, as well as other veterinary schools and practices, perceived themselves as crucial to informing public health debates and participating in actions to safeguard public health in the early to mid-twentieth century (Newspaper Cuttings 1930-1951). This positioning has come round again, apparent in the growing area of One Health, with its partnerships between medicine and veterinary medicine, primarily focused on zoonotic disease transmission and antimicrobial resistance.

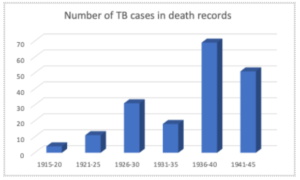

Edinburgh Zoo contended with outbreaks of avian TB, which appears to be the reason for an increase in TB cases from 1936 to 1940 (RZSS Register of Deaths). In some cases, zoo records include the location of TB in the animals’ bodies, making it possible to identify what was most likely avian TB.

TB cases noted in Death Records from 1915-1945

Ruminants can become reservoirs for the disease, with potential to lead to widespread infections in other zoo animals through faeces. TB in the lungs caused animal deaths, between 1936 and 1945, across a wide range of species at the zoo (RZSS Register of Deaths). Postmortems undertaken by the Dick Vet reveal further details of disease but do not name specific TB bacteria involved (see, for example, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College Postmortems 1941-43). Unlike cows, who were killed if they tested positive for bTB, Edinburgh Zoo animals were not tested and culled, instead dying of various forms of TB, as it may have been difficult to identify a cause of illness until postmortem.

A white oryx died of avian TB at Edinburgh Zoo in 1943 (photo: Shutterstock)

As with many other zoos, RZSS had roots in conceptions of zoos as places for public recreation or entertainment, showcasing species exotic to Scotland, while also providing what they considered health and wellbeing benefits to people through engagement with wildlife; this is evident in the annual report accounts from the period of 1915 to 1945 (see especially annual reports from 1941-1945 during the war years). RZSS in the early to mid-twentieth century saw itself as equally concerned about the impact of their practices on human and animal health and wellbeing, considering captivity better for the animals than a wild life of stress and uncertainty (Gillespie 1934); the latter can be challenged within a context of wild animal trade and a well-known history of colonial menageries and profit-driven enterprises (Flack 2018, Rothfels 2008). Many animals, live caught from India and colonial countries in Africa, perished during transport, failed to thrive upon arrival and/or direct contact with humans left them vulnerable to zoonotic diseases, such as TB (Hochadel 2022). Thus, Edinburgh Zoo, alongside other zoos in Europe, maintained an ethos tied to human health and wellbeing benefits of engagement with wild animals and linked to a colonial past.

Finally, SSPV focused on individuals, both human and other animal, to challenge what they considered the cruelty of vivisection and vaccinations built on animal experimentation. They saw other animals as deserving of compassion and fair treatment, in large part based on Evangelical Christian ideals and the positioning of women who drove campaigns (see Our Fellow Mortals magazines, an example in the references). SSPV archival materials reveal a concern for conditions of living and preventative measures that would keep bodies healthy, both human and animal. For instance, James C. Thomson, an influential figure for the SSPV, who developed nature cure approaches in Edinburgh, described the strain that milk production placed on dairy cow bodies in industrial farming, which resulted in hypocalcaemia (Thomson 1943); milk fever, caused by hypocalcaemia, was and still is a recurring illness of dairy cows, as studied by the Dick Vet and found in their archival material (see Papers Relating to Milk Fever Research). These animals became more susceptible to TB infection.

Evening News, 1939, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, Newspaper Clippings 1930-1951 (EUA IN2/6/2)

In terms of their anti-vaccination stance, the SSPV foreshadowed current anti-vaccination sentiment, as described in the US context:

‘Concerns about contamination, distrust in the medical profession, resistance to compulsory vaccination, and the situated locality of vaccine resistance are themes that resonate with contemporary vaccination skepticism. Recently, commentators on vaccination resistance have tended to see these themes as historically new in the late 20th century … Yet that view is historically inaccurate, and it obscures the fact that there has always been resistance to vaccination.’ (Hausman et al 2014)

But SSPV also had a unique positioning in their concern for animal welfare and health in relation to vaccination (not just human medical freedom) and other practices employed to treat or understand human diseases. They aligned with RZSS in their focus on the human health benefits of connection to nature, while diverging in their concern regarding use of animals, which often caused animal suffering. Thus, their perspective appears to foreshadow elements of the contemporary One Welfare approach, attempting a decentring of the human.

Collection stores at the Main Library

Through engagement with archival materials, we can see how animal welfare held a central place in work of the Dick Vet, RZSS and SSPV, and debates occurred in Scotland between 1915 and 1945 around the ways in which animal welfare, or the treatment of animals and their wellbeing, related to public health. This is not new debate and ideas now contained within current conceptions of One Health and One Welfare were expressed throughout the twentieth century. Historical records in the Dick Vet, RZSS and OneKind archives provide a wealth of relevant perspectives to be mined, to understand origins or precursors of concepts and to potentially inform equitable ways forward.

Please get in touch if you’d like to know more details about this project! The next blog post will shift our focus to women and how they feature uniquely in archival materials.

References (please note, the RZSS archive is in the process of being catalogued)

ArchivesSpace links to archival materials for the Dick Vet and OneKind

Andrew Flack, The Wild Within: Histories of a Landmark British Zoo, University of Virginia Press, 2018

Thomas H. Gillespie, Is it Cruel? A Study of the Condition of Captive and Performing Animals, Herbert Jenkins Ltd., 1934.

Bernice Hausman, Mecal Ghebremichael, Philip Hayek and Erin Mack, ‘Poisonous, filthy, loathsome, damnable stuff’: the rhetorical ecology of vaccination concern’, Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine (2014) 87(4), pp. 403-146, p. 413.

Oliver Hochadel, ‘Science at the Zoo: An Introduction’, Centaurus (2022), 64(3), pp. 561-590.

Newspaper Cuttings 1930-1951, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, EUA IN2/6/2, University of Edinburgh.

SSPV, Our Fellow Mortals, 1922, 25, p. 8, OneKind, 1618/1/4/2/1, University of Edinburgh.

Papers Relating to Milk Fever Research, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, EUA IN2/5/3, University of Edinburgh.

Postmortems 1941-43, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, EUA IN2, University of Edinburgh.

Nigel Rothfels, Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

RZSS Annual Reports, 1941-1945

RZSS Register of Deaths 1915-1937, 1937-1949, University of Edinburgh.

Scottish Branch of the National Veterinary Medical Association, ‘Memorandum from the Scottish Branch to the Economic Advisory Council’, Papers of the BVA, 1933, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, EUA IN2/5/2/20 University of Edinburgh.

James C. Thomson, ‘Pasteurised milk: a national menace’, 1943, Is All Disease Curable? Pamphlets and notes, 1942 – 1943, OneKind,1618/2/1/4/1/34, p. 4, University of Edinburgh.

Archival Research on Bacterial Infections, Part 1: One Health, One Welfare and Tuberculosis

This week, I introduce my short research project on bacterial infections, with specific focus on tuberculosis (TB) as a zoonotic disease; these are diseases that can move from one animal species (including humans) to another. After spending two and a half months immersed in archival materials, I realised that this focus provided a good means to explore different ideas of animal welfare and how welfare was implicated in public health issues between 1915 and 1945.

The OneKind archives in store at the CRC

The Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, Royal Zoological Society of Scotland and OneKind animal charity (formerly the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Vivisection or SSPV), all approached infectious disease management in ways that defined welfare and cruelty differently. While I revealed these differences in my research, I also considered whether espoused ideas could be seen as precursors to contemporary conceptions of One Health or One Welfare. Here I’ll share a quick introduction to One Health and One Welfare and a bit of background about TB in the UK. Later this week, I’ll share my findings on this topic based on archival research.

What do we mean by One Health and One Welfare?

The concept of One Health (OH) was first referred to in 2003 as response or means to address the public health threat of zoonotic diseases. OH has been championed primarily by veterinarians (Cassidy 2018). The international One Health High Level Expert Panel developed a globally recognised definition:

‘One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems. It recognizes the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and inter-dependent.’ (Mettenleiter et al 2023)

But One Health has been criticised for being too anthropocentric and not adequately attending to animal welfare and wellbeing (Lindenmayer and Kaufman 2021). One Welfare is meant as a corrective and focuses on interconnections between animal welfare and wellbeing, human wellbeing and the environment, thus extending the One Health focus only on health (Pinillos 2018). The One Welfare Framework, developed by Pinillos (2018), includes themes that give equal or at least greater consideration to animals alongside humans in environments. These themes include:

- interconnections between animal abuse, human abuse and neglect;

- socio-economic aspects linked to animal welfare;

- connection between farm animal welfare, farmer well-being and food security;

- conservation, sustainability and connections between biodiversity, environment and animal-human wellbeing.

One Welfare also focuses on prevention, to understand ‘root causes and drivers’ of risks to health and wellbeing. I considered these concepts when investigating organisational approaches to animal welfare and human health in the archival materials. Now a brief introduction to the history of TB in the UK.

Dairy cows (photo: shutterstock)

Background: TB in the UK

TB is an ancient disease in the context of Europe and the UK. There are three types of TB that feature in the archival collections: Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) which causes disease in humans and can infect other mammals and parrots (Schneider et al 2008), M. bovis or bTB which causes TB in cows and infects humans and other animals through meat and milk product consumption (McFarlane 1990), and M. avium which primarily afflicts birds but can occasionally infect humans and other animal species (Blessington et al 2021).

Many individuals are resistant to serious infection by M. tuberculosis, but certain factors cause vulnerability including living conditions, diet (malnutrition), age and suffering from other illnesses (McFarlane 1990). This type of TB became most virulent in the nineteenth century in the UK and Europe in overcrowded conditions with poverty but declined in the twentieth century; increases occurred during the world wars due to increased conditions of impoverishment (Glaziou et al 2018). Edinburgh championed a campaign to fight TB that became the root of the national campaign in the late nineteenth century (McFarlane 1990). In 1882, Robert Koch identified and isolated the tubercle bacillus, grew it in animal serum and introduced it into laboratory animals who then developed TB (Barberis et al 2017). A vaccine, Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG), discovered by scientists at the Pasteur Institute, derived from a bovine TB strain, was trialled successfully on animals in 1919, following Koch’s work, with use of the vaccine on infants by 1924 (Luca and Mihaescu 2013). BCG successfully prevents disease in children, but immunity diminishes with time so that adults have weakened protection (Fatima et al 2020). Despite a vaccine and attempts to improve upon it, TB has not been eradicated, still considered a public health issue in Scotland (Public Health Scotland 2023).

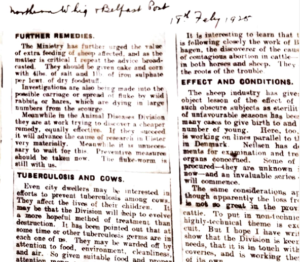

Northern Whig & Belfast Post, 1925, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, Newspaper Clippings 1923-1929 (EUA IN2/6/1)

Cases of bovine TB were lower than human TB historically in human populations in the UK, but concerning from a public health perspective due to child deaths (Waddington 2004). Infected cow’s milk and meat caused infection in humans. Milk, if properly pasteurised, was safe to drink, but most milk was unpasteurised up to 1939, with an anti-pasteurisation campaign influential between 1900 to 1930 (Atkins 2000); divisions formed even within the medical profession, with some doctors for and some against pasteurisation. The UK Government ‘Milk in Schools’ programme, to address malnourishment in British children, a public health issue, led to a greater number of children at risk of contracting bTB from infected milk during this time period (Atkins 2000). Other measures to reduce public health risk from bovine TB, aside from pasteurisation, developed from 1920 included a skin test for cattle and in the 1950s, compulsory testing of cows and culling of those positive for TB (Waddington 2004).

Finally, while transmission to humans has been considered low risk, M. avium infects those with compromised immune systems, and has been considered a public health concern. A vaccine has not been developed for avian TB, and treatment with antibiotics could lead to antimicrobial resistance, so responses to infections in farmed birds such as chickens, for instance, involved killing infected birds and preventative measures (Kwaghe et al 2015).

Look out for the next blog post where I’ll share some of my findings!

References

Peter Atkins, ‘The pasteurisation of England: the science, culture and health implications of milk processing, 1900-1950’, in David Smith and Jim Phillips (Eds.), Food Science, Policy and Regulation in the Twentieth Century: international and comparative perspectives, Abingdon: Routledge, 2000, pp. 37-52, 40.

I. Barberis, N.L. Bragazzi, L. Galluzzo and M. Martini, ‘The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch’s bacillus’, Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene (2017) 58(1), pp. E9-E12, E11.

Jacque Blessington, Judie Steenberg, Terry M. Phillips, Margaret Highland, Corinne Kozlowski and Ellen Dierenfeld, ‘Biology and Health of Tree Kangaroos in Zoos’, in Lisa Dabek, Peter Valentine, Jacque Blessington and Karin R. Schwartz (eds.), Biodiversity of World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes, Academic Press, 2021, pp. 285-307.

Angela Cassidy, ‘Humans, other animals and “one health” in the early twenty-first century’, in Abigail Woods, Rachel Dentinger, Angela Cassidy and Michael Bresalier (eds.), Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine: One Health and its Histories. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, pp. 193-236,193.

Samreen Fatima, Anjna Kumari, Gobardhan Das and Ved Prakash Dwivedi, ‘Tuberculosis vaccine: A journey from BCG to present’, Life Sciences (2020) 252, p. 117594.

Philippe Glaziou, Katherine Floyd and Mario Raviglione, ‘Trends in tuberculosis in the UK’, Thorax (2018) 73, pp. 702-703, 702.

A.V. Kwaghe, M.D. Ndahi, J.G. Usman, C.T. Vakuru, V.N. Iwar, J.A. Ameh and A.G. Ambali, ‘A review on avian tuberculosis (Avian mycobacteriosis)’, CABI Reviews (2015), pp. 1–17, 2.

Joann Lindenmayer and Gretchen Kaufman, ‘One health and one welfare’, in Tanya Stevens (ed.), One Welfare in Practice: the role of the veterinarian. Abingdon: CRC Press, 2021, pp. 1-30, 1.

Simona Luca and Traian Mihaescu, ’History of BCG Vaccine’, Maedica (Bucur) (2013) 8(1), pp. 53-58, 54.

Neil McFarlane, Tuberculosis in Scotland, 1870-1960, PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 1990, p. 11.

T.C. Mettenleiter, W. Markotter, D.F. Charron et al, ‘The One Health high-level expert panel (OHHLEP)’. One Health Outlook (2023) 5 (18), pp. 1-8, 3.

Rebeca García Pinillos, ‘One welfare, companion animals and their vets’, Companion Animal (2018) 23 (10), p. 598.

Public Health Scotland, ‘2021 Tuberculosis Annual Report Published for Scotland’ (21, February, 2023), 2021 Tuberculosis Annual Report for Scotland published – News – Public Health Scotland, accessed [22 February 2024].

Susanne Schneider, Julian Schlömer, Maria-Elisabeth Krautwald-Junghanns and Elvira Richter, ‘Transmission of tuberculosis between men and pet birds: a case report’, Avian Pathology (2008) 37(6), pp. 589-592.

Keir Waddington, ‘To Stamp Out “So Terrible a Malady”: Bovine Tuberculosis and Tuberculin Testing in Britain, 1890–1939’, Medical History (2004) 48(1), pp. 29-48, 29.

AI, Theological Libraries … and me

The University of Edinburgh hosted the Association of British Theological and Philosophical Libraries conference this year at New College on 21-23 March. As usual there was the opportunity for discovering fascinating and historic libraries, including (of course) New College Library, the National Museum of Library of Scotland and the Signet Library.

Computer17293866, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

A key focus this year was Artificial Intelligence or AI, and Prof Nigel Crook from Oxford Brookes University opened the conference, speaking about ‘Generative AI and the Chatbot revolution’, and concluding that while he didn’t predict a future like the one in the Terminator, this couldn’t entirely be ruled out. 😊 Following this was Professor Paul Gooding from the University of Glasgow, with an engaging talk on ‘Applying AI to Library Collections’. He identified a key challenge for libraries as being the control of AI development by a handful of technology firms – the forces driving AI tools are not situated in the library sector. How can libraries play a part in AI innovation? Read More

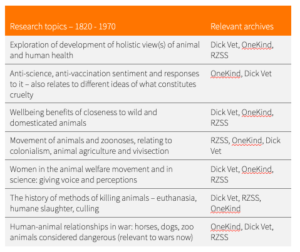

Research and the One Health Archival Collections

Hello, I’m Elizabeth, the postdoctoral researcher on the One Health archival project! During the Wellcome Trust grant, I was employed for five months from October 2023 to the start of March 2024 to develop academic engagement with the archival material and undertake a short research project. Thanks to funding from Heritage Collections, I can continue for two more months until early May, focusing on engagement and another short research project. I will spend the next month blogging to introduce research strands identified across the collections that might be of interest to researchers/students, share short research projects I’ve undertaken, and our academic engagement activities so far. By doing this, you’ll really get a flavour for the richness of the collections as a resource for research.

RZSS Animal Arrival and Death Records

Just a quick introduction to my background! I have a PhD in environmental policy and ethics, with focus on biodiversity conservation, but more recently I have undertaken degrees in anthropology, in the subfield of anthrozoology, where we study human-animal relationships and interactions, considering socio-cultural, political contexts. My previous research projects have primarily involved captive wild animals in zoos and circuses, compassionate conservation and human-wildlife conflict and coexistence. I had previously undertaken research on Charles Darwin that introduced me to digital archival research, but I had not engaged directly with archival material – this is an exciting, new world to be immersed in. Thank you to Fiona Menzies, Project Archivist and lead, for introducing me to it!

Me and my cat, Reilly, who is known well at the Dick Vet due to his many rare health conditions!

The archival materials are fascinating in so many respects, windows into specific organisations in Edinburgh and how they were located within wider debates in Scotland and the UK about animal health, welfare, conceptions of animal cruelty, public health and the roles and perceptions of women in caring within communities, for instance. More on research possibilities in the next blog post! In the meantime, do get in touch if this post has already piqued your interest: you can comment on the blog post or reply to me directly at elizabeth.vandermeer@ed.ac.uk.

Sneak peak at research strands:

Research streams that cross the collections

Systematic Reviews: five frequently asked questions

When the Academic Support Librarians provide help for students and researchers who are conducting large-scale reviews, such as systematic and scoping reviews, we find that often the same questions will come up. This blog post aims to answer five of your frequently asked questions about systematic reviews and provide some useful resources for you to explore further.

For even more advice about systematic review guidance, see the library’s subject guide on systematic reviews and LibSmart II: Literature Searching for Systematic Reviews.

Now let’s dive in to five Frequently Asked Questions…

1. What is a systematic review, and how does it differ from other types of literature review?

According to the Cochrane Collaboration, a leading group in the production of evidence synthesis and systematic reviews;

systematic reviews are large syntheses of evidence, which use rigorous and reproducible methods, with a view to minimise bias, to identify all known data on a specific research question.1

This is done by a large, complex literature search in databases and other sources, using multiple search terms and search techniques.

Traditional literature reviews, such as the literature review chapter in a dissertation, don’t usually apply the same rigour in their methods because, unlike systematic reviews, synthesise all known data on a topic. Literature reviews can provide context or background information for a new piece of research, or can stand alone as a general guide to what is already known about a particular topic2.

What about scoping reviews?

There are other review types in the systematic review “family”3. You may have also heard of scoping reviews. These are similar to systematic reviews, in that they employ transparent reporting of reproducible methods and synthesise evidence, but they do so in order to identify knowledge gaps, scope a body of literature, clarify concepts or to investigate research conduct4. Literature searching for scoping reviews will be similarly comprehensive, but may be more iterative than in systematic reviews.

Useful resources:

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J, 26(2), 91-108.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M.D.J., Stern, C. et al. (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18, 143.

2. Which databases should I use?

Image by AcatXIo • So long, and thanks for all the likes! from Pixabay

Choosing appropriate databases in which to search is important, as it determines the comprehensiveness of your review. Using multiple databases means you are searching across a wider breadth of literature, as different databases will index different journals.

The list of Databases by Subject and the library subject guides can guide you to key databases for your topic.

To get an idea which databases are best suited to yield the data you need, you can also look at published systematic reviews on similar topics to yours, to see which databases those authors used.

The number of databases you use to search will vary depending on the research query, but it is important to use multiple databases to mitigate database bias and publication bias. More important than the number of databases is using the appropriate databases for the subject to find all the relevant data.

Useful resources:

3. What is grey literature and how do I find it?

Image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

You may have read that you should include grey literature in your sources of data for your review.

The term ‘grey literature’ refers to a wide range of information which is not formally or commercially published, and which is often not well represented in library research databases.

Using grey literature will help you to find current and emerging research, to broaden your research, and to mitigate against publication bias.

Sources and types of grey literature will vary between research topics. Some examples include:

|

|

Key sources of grey literature

Finding grey literature can be tricky because it can vary a lot in type and where it’s published. To help you, the Library’s subject guide has some key sources of grey literature to explore. The Library also has several databases which include records of dissertations and theses, which can be a source of relevant data for your review.

Another useful approach is using a domain search in Google to search within the websites of key organisations or professional bodies in your subject. For example, searching site: followed by a domain in Google:

site:who.int will search within the WHO website.

site:gov.uk will search only websites with a url that ends .gov.uk

4. How do I translate searches between databases?

Image by 200 Degrees from Pixabay

You may have heard that you need to ‘translate’ your search. This simply means taking the search you have developed in the database and optimising it to work best in a different database.

The way you tell a database to search for a term in the title of the record, or the command for searching for terms in close proximity to each other, will be different between databases and platforms.

For example, in the medical literature database Ovid Medline, the search for a subject heading on gestational diabetes is Diabetes, Gestational/ whereas the nursing database EbscoHost CINAHL uses MH “Diabetes Mellitus, Gestational”. Both the syntax that refers to a subject heading needs to be translated (/ to MH) and the subject heading itself is different (Diabetes, Gestational to Diabetes Mellitus, Gestational).

You can practice translating a search in the Learn course LibSmart II in the module on Literature Searching for Systematic Reviews. We also have a Library Bitesize session on translating literature search strategies across databases coming up in April.

Useful resources:

- Polyglot search tool: A tool for translating search strings across multiple databases.

- Database syntax guide [PDF] by Cochrane

5. Do you have any training for systematic review?

Image by José Miguel from Pixabay

We do! The Learn course LibSmart II: Advance Your Library Research has a whole module on Literature Searching for Systematic Reviews. LibSmart II can be found in Essentials in Learn. If you don’t see it there, contact your Academic Support Librarian and we’ll get you enrolled.

We also have several recorded presentations on systematic reviews on our Media Hopper channel, including ‘What is a systematic review dissertation like?’ and ‘How to test your systematic review searches for quality and relevance’.

For self-paced training on the whole process of conducting a systematic review, Cochrane Interactive Learning has modules created by methods experts so you build your knowledge one step at a time. Perfect for what can be an overwhelming research method.

If you are a student conducting a systematic review, we can highly recommend the book Doing a Systematic Review (2023). With a friendly, accessible style, the book covers every step of the systematic review process, from planning to dissemination.

—–

The FAQs in this post are taken from the library subject guide on Systematic Review Guidance where you can find even more information and advice about conducting large-scale literature reviews.

You can contact your Academic Support Librarian for advice on literature searching, using databases, and managing the literature you find.

—–

References

- Higgins, J., et al., Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). 2023, Cochrane.

- Mellor, L. The difference between a systematic review and a literature review, Covidence. 2021. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/blog/the-difference-between-a-systematic-review-and-a-literature-review/. (Accessed: 20 March 2024).

- Sutton, A., et al., Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 2019. 36(3): p. 202-222.

- Munn, Z., et al., Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2018. 18(1): p. 143.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....