How often do you walk past a 1000 year old rune stone? The answer is every day, if you work or study near the Main Library!

Earlier this year I completed a project photographing James Skene’s Album of Sketches in greater detail. When I came across his runestone illustration again I was intrigued and did some research, making the surreal discovery that the subject was a 3 minute walk away. At 50 George Square behind the Scandinavian Studies Department, stands a Swedish runestone with a curious history. This 1.3 tonne granite stone found its new home here at the university in 2019, having been moved several times prior.

To give a very brief outline of its history, the runestone, known as U1173, is an 11th century Viking age runestone originally from Lilla Ramsjö in present-day Morgongåva, Heby Municipality in Sweden. It was dug out of the ground on an estate, packed up on a ship that arrived in Leith, and donated to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1787 by Sir Alexander Seton of Preston and Ekolsund. The Society is the oldest antiquarian society in Scotland (and the second oldest in Britain), founded in 1780. The stone was one of the earliest acquisitions by the Society, and was placed outside Chessel’s Buildings in the Canongate. In 1804 it was moved up to Castle Hill, before being moved yet again “with difficulty” to a steep slope in Princes Street Gardens in 1821 as a gift to the Princes Street Proprietors. The stone remained largely unnoticed in the Gardens for many years due to its hard to reach position.

During the year of History, Heritage and Archaeology in 2017, the Society discussed conserving and moving the stone to a new location which would be accessible and visible to everyone year-round, and the University of Edinburgh was chosen, though it is under the care of National Museums Scotland. In the autumn of 2019 the runestone was unveiled in its new location at 50 George Square.

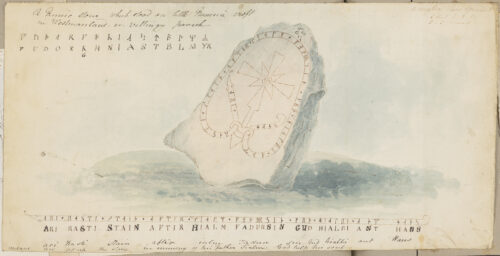

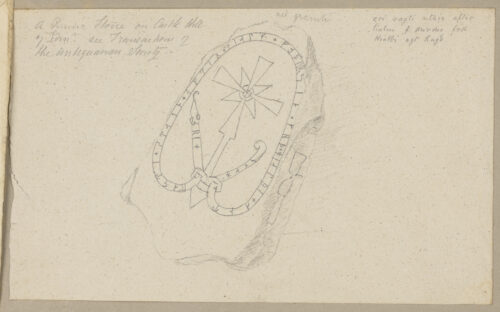

I came across the runestone illustrations when I first photographed James Skene’s sketchbook in 2021. At this time, the digitisation was only of page spreads rather than individual sketches (you can find the blog post here). I must admit when I first glanced across them I had romantic notions that it could have been something found on a remote stretch of the highlands or islands, areas often credited with archaeological finds such as Viking hoards. It is now apparent that when Skene illustrated the stone, it was due to his close personal involvement in Societies, including the Geological Society of London and – you guessed correctly – the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, around 1820. This neatly aligns with our metadata of 1793-1834 as the dates attributed to the Album of Sketches, as well as the stone’s location in Princes Street Gardens around that time.

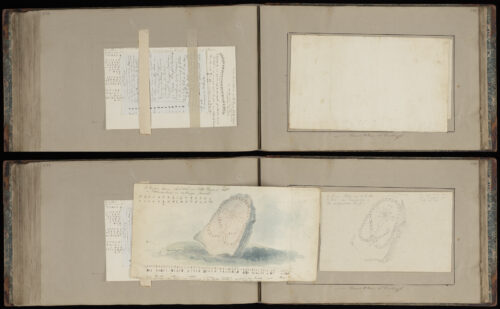

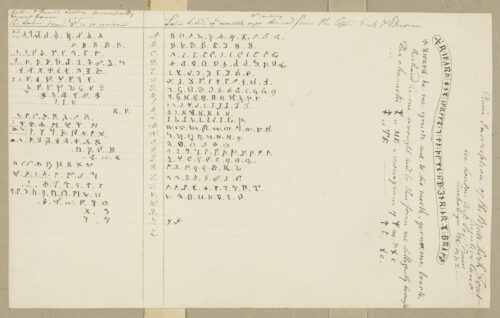

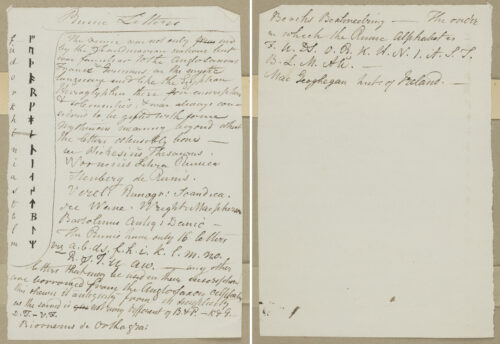

I find it intriguing that James Skene felt compelled to make detailed notes and illustrations of the runestone, even going as far as notating the translation of each rune. He has also made a basic ‘pocket slip’ of two glued strips of paper to keep these notes secure in the sketchbook, as well as making the double-sided pages easily accessible and portable.

The written content on the stone can be summarised below. The ‘+’ sign denotes the end of the word, and the writing begins at the snake’s head, and wraps around the stone before ending at the tail.

Transliteration into Latin characters: ‘ ari + rasti + stain + aftir + (h)ialm + faþur sin + kuþ + hialbi + ant hans

Transcription into Old Norse: Ari ræisti stæin æftiʀ Hialm, faður sinn. Guð hialpi and hans.

Translation into English: “Ari raised the stone in memory of Hjalmr, his father. May God help his spirit.”

Erik was a renowned runecarver and there are examples of his other work in Sweden. He was commissioned by a man named Ari to honour his father Hjalmr. One or both of the men were Christian, evident by the snake as a symbol of the old Norse gods, and the cross as a symbol of Christianity. Combining the new faith with the old wasn’t uncommon in the later days of the Viking Age. The art on this runestone is typical for Erik’s earlier work featuring a large prominent cross and a snake seen from above, as well as the runes A and N in the shape of short twig runes. This runestone was likely created at the crossover point when Christianity was coming to dominate the local culture.

An attempt was made in 2012 to try and return the stone back to Sweden, but unfortunately it was found to be too difficult logistically. In 2014 a replica of the runestone was made by Kalle Runecarver, one of the only people in the world carving runestones through traditional methods. More can be found about this project here.

There are only 3 Swedish runestones in the UK, and the other two are in the Ashmolean Museum. This is the only one that is still outside, where Swedish rune stones were supposed to be located where people would see and interact with them.

In our department we are privileged to work with a variety of special collections, but often they are kept hidden and protected due to their fragility. This incredible object is accessible in a public space to everyone, at any time. It has witnessed the events of the last 1000 years and has been exposed to the elements yet is still in remarkable condition. Take a small detour and witness the stone for yourself next time you’re in the area!

Juliette Lichman, Photographer

What a lovely piece. Thank you for sharing this information! I love how you consider how the stone has seen all these things happen over the centuries too. I often thing about this wieth statues and so on too. 🙂

Hi Rachel,

Many thanks for your kind words! It’s funny how we are used to being around lots of historical sites and artefacts and think of them being in our lives when it’s very much the opposite!

Juliette