Now for the next part in this series on bacterial infections, sharing some findings from archival research!

The Dick Vet, RZSS and OneKind, or SSPV (Scottish Society for the Prevention of Vivisection), each related animal health and welfare to human health, but in somewhat different ways. All three organisations acknowledged the conditions that could lead to zoonotic disease transmission and outbreaks of disease such as TB; they noted poor welfare conditions reducing animals’ resistance, and poor health in the case of humans (diet, etc), along with crowded and unhygienic conditions. But they presented different perspectives in the early to mid-twentieth century on how to tackle public health issues of bacterial infections, based on different understandings of animal welfare and cruelty.

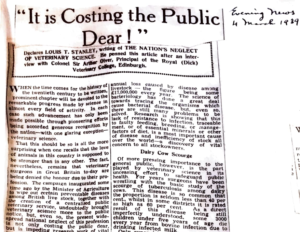

ArchivesSpace – where you’ll find archival records for the Royal (Dick) Veterinary College

The Dick Vet attended to animal health often in the service of human health, especially in the case of animals in agriculture, their main practice in the mid 19th to early 20th centuries prior to the burgeoning of companion animal ownership. The Dick Vet contributed to the Scottish Branch of the National Veterinary Medicine Association (NVMA) and its scheme for the Eradication of Bovine TB, which recognised that stress in cows reduced resistance to disease:

‘It may also be said that the body economy of the individual cows moved from market to market soon after calving is often so upset that resistance to new infection or infection already established is greatly reduced. The spread of the disease is encouraged in this way’. (Scottish Branch of NVMA 1933)

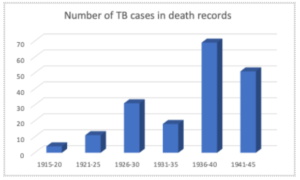

While treating individuals, the veterinary focus remained on a wider good, of populations of humans and animals. This approach allowed the sacrifice of individuals to vivisection, or animal experimentation, in order to advance understandings of diseases and treatments. The Dick Vet, as well as other veterinary schools and practices, perceived themselves as crucial to informing public health debates and participating in actions to safeguard public health in the early to mid-twentieth century (Newspaper Cuttings 1930-1951). This positioning has come round again, apparent in the growing area of One Health, with its partnerships between medicine and veterinary medicine, primarily focused on zoonotic disease transmission and antimicrobial resistance.

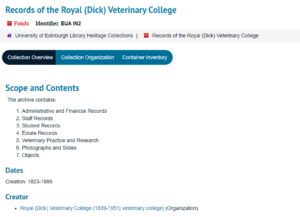

Edinburgh Zoo contended with outbreaks of avian TB, which appears to be the reason for an increase in TB cases from 1936 to 1940 (RZSS Register of Deaths). In some cases, zoo records include the location of TB in the animals’ bodies, making it possible to identify what was most likely avian TB.

TB cases noted in Death Records from 1915-1945

Ruminants can become reservoirs for the disease, with potential to lead to widespread infections in other zoo animals through faeces. TB in the lungs caused animal deaths, between 1936 and 1945, across a wide range of species at the zoo (RZSS Register of Deaths). Postmortems undertaken by the Dick Vet reveal further details of disease but do not name specific TB bacteria involved (see, for example, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College Postmortems 1941-43). Unlike cows, who were killed if they tested positive for bTB, Edinburgh Zoo animals were not tested and culled, instead dying of various forms of TB, as it may have been difficult to identify a cause of illness until postmortem.

A white oryx died of avian TB at Edinburgh Zoo in 1943 (photo: Shutterstock)

As with many other zoos, RZSS had roots in conceptions of zoos as places for public recreation or entertainment, showcasing species exotic to Scotland, while also providing what they considered health and wellbeing benefits to people through engagement with wildlife; this is evident in the annual report accounts from the period of 1915 to 1945 (see especially annual reports from 1941-1945 during the war years). RZSS in the early to mid-twentieth century saw itself as equally concerned about the impact of their practices on human and animal health and wellbeing, considering captivity better for the animals than a wild life of stress and uncertainty (Gillespie 1934); the latter can be challenged within a context of wild animal trade and a well-known history of colonial menageries and profit-driven enterprises (Flack 2018, Rothfels 2008). Many animals, live caught from India and colonial countries in Africa, perished during transport, failed to thrive upon arrival and/or direct contact with humans left them vulnerable to zoonotic diseases, such as TB (Hochadel 2022). Thus, Edinburgh Zoo, alongside other zoos in Europe, maintained an ethos tied to human health and wellbeing benefits of engagement with wild animals and linked to a colonial past.

Finally, SSPV focused on individuals, both human and other animal, to challenge what they considered the cruelty of vivisection and vaccinations built on animal experimentation. They saw other animals as deserving of compassion and fair treatment, in large part based on Evangelical Christian ideals and the positioning of women who drove campaigns (see Our Fellow Mortals magazines, an example in the references). SSPV archival materials reveal a concern for conditions of living and preventative measures that would keep bodies healthy, both human and animal. For instance, James C. Thomson, an influential figure for the SSPV, who developed nature cure approaches in Edinburgh, described the strain that milk production placed on dairy cow bodies in industrial farming, which resulted in hypocalcaemia (Thomson 1943); milk fever, caused by hypocalcaemia, was and still is a recurring illness of dairy cows, as studied by the Dick Vet and found in their archival material (see Papers Relating to Milk Fever Research). These animals became more susceptible to TB infection.

Evening News, 1939, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, Newspaper Clippings 1930-1951 (EUA IN2/6/2)

In terms of their anti-vaccination stance, the SSPV foreshadowed current anti-vaccination sentiment, as described in the US context:

‘Concerns about contamination, distrust in the medical profession, resistance to compulsory vaccination, and the situated locality of vaccine resistance are themes that resonate with contemporary vaccination skepticism. Recently, commentators on vaccination resistance have tended to see these themes as historically new in the late 20th century … Yet that view is historically inaccurate, and it obscures the fact that there has always been resistance to vaccination.’ (Hausman et al 2014)

But SSPV also had a unique positioning in their concern for animal welfare and health in relation to vaccination (not just human medical freedom) and other practices employed to treat or understand human diseases. They aligned with RZSS in their focus on the human health benefits of connection to nature, while diverging in their concern regarding use of animals, which often caused animal suffering. Thus, their perspective appears to foreshadow elements of the contemporary One Welfare approach, attempting a decentring of the human.

Collection stores at the Main Library

Through engagement with archival materials, we can see how animal welfare held a central place in work of the Dick Vet, RZSS and SSPV, and debates occurred in Scotland between 1915 and 1945 around the ways in which animal welfare, or the treatment of animals and their wellbeing, related to public health. This is not new debate and ideas now contained within current conceptions of One Health and One Welfare were expressed throughout the twentieth century. Historical records in the Dick Vet, RZSS and OneKind archives provide a wealth of relevant perspectives to be mined, to understand origins or precursors of concepts and to potentially inform equitable ways forward.

Please get in touch if you’d like to know more details about this project! The next blog post will shift our focus to women and how they feature uniquely in archival materials.

References (please note, the RZSS archive is in the process of being catalogued)

ArchivesSpace links to archival materials for the Dick Vet and OneKind

Andrew Flack, The Wild Within: Histories of a Landmark British Zoo, University of Virginia Press, 2018

Thomas H. Gillespie, Is it Cruel? A Study of the Condition of Captive and Performing Animals, Herbert Jenkins Ltd., 1934.

Bernice Hausman, Mecal Ghebremichael, Philip Hayek and Erin Mack, ‘Poisonous, filthy, loathsome, damnable stuff’: the rhetorical ecology of vaccination concern’, Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine (2014) 87(4), pp. 403-146, p. 413.

Oliver Hochadel, ‘Science at the Zoo: An Introduction’, Centaurus (2022), 64(3), pp. 561-590.

Newspaper Cuttings 1930-1951, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, EUA IN2/6/2, University of Edinburgh.

SSPV, Our Fellow Mortals, 1922, 25, p. 8, OneKind, 1618/1/4/2/1, University of Edinburgh.

Papers Relating to Milk Fever Research, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, EUA IN2/5/3, University of Edinburgh.

Postmortems 1941-43, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, EUA IN2, University of Edinburgh.

Nigel Rothfels, Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

RZSS Annual Reports, 1941-1945

RZSS Register of Deaths 1915-1937, 1937-1949, University of Edinburgh.

Scottish Branch of the National Veterinary Medical Association, ‘Memorandum from the Scottish Branch to the Economic Advisory Council’, Papers of the BVA, 1933, Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, EUA IN2/5/2/20 University of Edinburgh.

James C. Thomson, ‘Pasteurised milk: a national menace’, 1943, Is All Disease Curable? Pamphlets and notes, 1942 – 1943, OneKind,1618/2/1/4/1/34, p. 4, University of Edinburgh.