LONDON, UK – 4 DECEMBER 2018: A statue of the English suffragist and union leader Millicent Fawcett, an early feminist campaigner for women’s suffrage (Photo: Shutterstock).

Welcome to this series on research for the One Health archival project!

This week, I will present a bit about my current research project with Dr. Alette Willis, Chancellor’s Fellow and Senior Lecturer in the School of Health in Social Science. We have been looking at the roles of women in care practices in the early twentieth century, through evidence we find across OneKind (SSPV), the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) and the Royal (Dick) Veterinary College archival materials. I’ll provide a quick glimpse into what we’ve found so far regarding women’s caring roles during the time period of 1910-1930 in the three organisations.

OneKind (SSPV): women as moral compass and source of compassion

Some women involved in women’s suffrage in the UK in the early twentieth century also became anti-vivisectionists. We found that women were central to the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Vivisection (SSPV), and many also proved active in other social movements. Women in the UK experienced the threat of government-sanctioned and medically applied control over their bodies after the passing of the Contagious Disease Act 1866 (see this article on the Victorian Web for an overview). Women, then, could identify with the suffering of animals whose bodies were controlled completely during acts of vivisection.

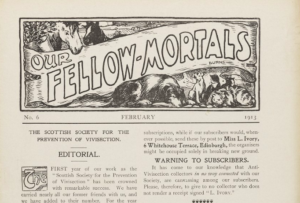

Image of Our Fellow Mortals Magazine, volume number 6, February 1913, SSPV

But, the brutality of vivisection was also railed against as corrupting good souls, and women in the SSPV expressed a neo-romanticism that rejected material and impassionate science, apparent in their magazine, Our Fellow Mortals, with volumes published from 1911 to 1925; my previous research of cultural attitudes towards animals in France showed a similar perception in the 19th century of the corrupting power of witnessing or participating in acts of brutality or cruelty towards animals. Examples can be found in the SSPV magazine of women characterised, and characterising themselves, as the moral compass of society, the source of compassion. For instance, the SSPV included a quote from poet George Barlow’s essay, ‘Science and Sympathy’, in volume number 6 of the magazine, February 1913, page 7:

‘More and more, for good or evil, women are beginning to study physiology and to take active part in medical practice … We must remember that the feminine faculty of tenderness is the saving factor in the coarse and selfish world. If we teach women to be cruel, our folly will re-act upon ourselves in unforeseen and terrible ways … No amount of scientific knowledge, no fabulous increase of material comforts or luxuries, would ever compensate mankind for the loss of its one most priceless faculty, the gift of loving-tenderness’ (1618/1/4/2/1)

Thus, women who entered medicine or veterinary medicine, could lose their feminine compassion. This perception of women also laid the burden of caring about and for other animals at their feet; women should care deeply about the fate of animals used in vivisection, as well as animals killed for food and other goods. This positioning of women is apparent in flyers held by the SSPV from the Council of Justice to Animals, in this case an appeal to women regarding humane slaughtering, by the Secretary of the Council, Violet Woods, most likely dated in the early to mid 1920s:

‘It is to the women of this country that we must appeal to bring about this reform. Will they fail to realise their responsibility? The fate of thirty million animals slaughtered every year in these isles is in their hands, and humanity cries aloud to them to do their duty. Another year may prove whether it may be proclaimed to foreign lands that every animal in Britain has a painless death, because the women realised their sufferings, realised their own responsibility, exercised their power, and have done their duty.’ (1618/2/3/2/2)

Women within the SSPV cared about animals but were not necessarily ‘on the ground’ caring for, and they represented the upper classes.

Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS): unpaid labour and generosity

Red Pandas at Edinburgh Zoo (Photo: Elizabeth Vander Meer, 2024)

Women appear in the RZSS archival records in terms of caring for animals, and plants, in the form of unpaid labour, undertaking keeper work and gardening on zoo grounds. Unpaid labour defines women’s involvement in care practices at Edinburgh Zoo in the early twentieth century, with wives of keepers, architects and garden designers fulfilling these roles alongside their husbands; this was the case for zoo founder, Thomas Gillespie, whose wife, Mary Elizabeth, supported many aspects of zoo animal care and management. Women also cared about animals and the establishment through monetary, food and animal donations. Women who donated money or food could be characterised as inhabiting higher socio-economic strata in Edinburgh, evident in RZSS Annual Reports for the period. Several women appear in paid work as refreshment manageresses, as described in the RZSS Annual Reports.

We can find what could be considered an anthroporphising of animals in the case of descriptions of mothers and mothering found in the RZSS Annual Reports. This example is useful to consider here, from the 1930 Annual Report, page 12:

‘For the first time in the history of the Park a litter of three polar bear cubs was born, but “Sheila” did not prove a good mother, and devoured them as soon as they were born’

Polar bears, usually males, eat cubs when resources are scarce in wild conditions, but females are protective of young (National Geographic has shared footage of a male polar bear killing and eating a cub, February 2016); in this case, the zoo context at the time could be considered carefully to understand what triggered cannibalistic behaviour in the female.

Royal (Dick) Veterinary College: the absence of women

Women are conspicuously absent from the veterinary archival materials, due to the late allowance of women into the College, by 1948. But Alette and I are approaching the archive in terms of this absence and the presence of men who are caring for animals. This research is work in progress, so I will share more if I can in a later blog post!