Cataloguing the correspondence of zoologist/animal breeder James Cossar Ewart (1851-1933), I have been intrigued by the various ‘life stories’ which emerge from the letters. Periodically I will be including some highlights in a series of posts entitled ‘letters in the limelight’ .

Cataloguing the correspondence of zoologist/animal breeder James Cossar Ewart (1851-1933), I have been intrigued by the various ‘life stories’ which emerge from the letters. Periodically I will be including some highlights in a series of posts entitled ‘letters in the limelight’ .

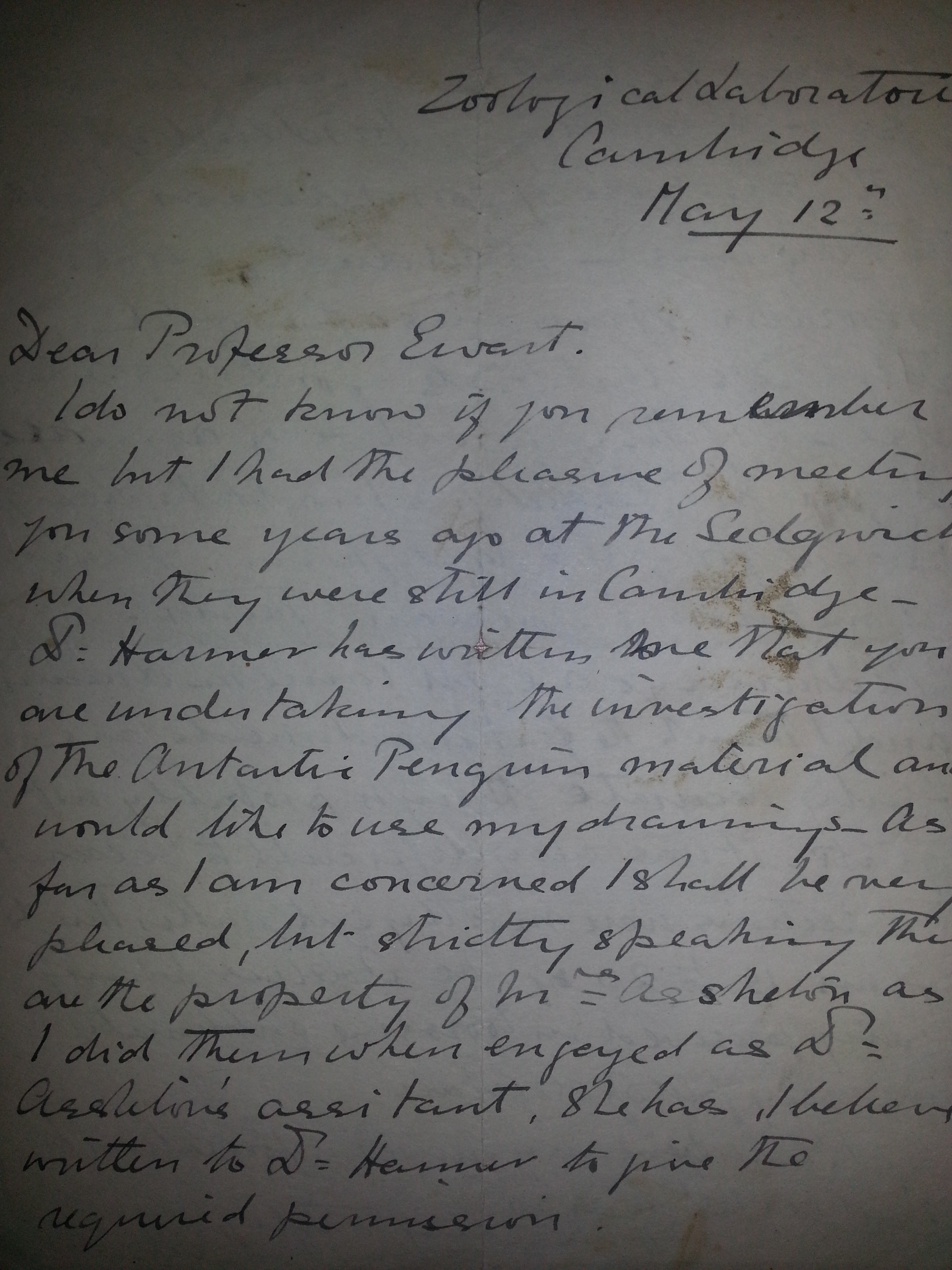

Last week’s ‘Letters in the Limelight’ focused on Dorothy Thursby-Pelham’s drawings of penguin embryos from Captain Scott’s ill-fated expedition to the Antarctic; this week, we are staying with the theme of exploration by looking at a letter (dated 25 June 1915) to Ewart from the Edinburgh-born zoologist and oceanographer Sir William Abbott Herdman (1858-1924). Ewart had evidently written to Herdman, who was then Professor of Natural History at the University of Liverpool, requesting some biographical details, to which Herdman modestly replied: ‘what an awful question you ask me! What on earth am I to say? I am the last person who ought to answer it. Will Who’s Who not supply what you want? However I suppose I must help you with any facts I can think of…’ He manages to recover from his reticence sufficiently to provide a brief career history, although he is careful to stress that ‘I had nothing to do of course with the Challenger expedition – was a school-boy at the Edin[burgh] Academy at the time; but I was one of Wyville Thomson’s young men at the ‘Challenger Office’ after he came home.’

Herdman of course refers to the HMS Challenger expedition which visited all of the world’s oceans except the Arctic between 1872 and 1876. The expedition aimed primarily to determine deep sea physical conditions such as temperature and ocean currents, although other forms of investigation, including those of a biological nature, were also carried out. In charge of the scientific staff on board was Charles Wyville Thompson (1830-1882), whom Ewart was to succeed as Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh. Thompson’s location decided that the ‘Challenger Office’ mentioned by Herdman was set up in Edinburgh in order to analyse the findings of the expedition. The resulting Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of HMS Challenger was as monumental as the trip itself, appearing in 50 volumes up until 1895, and much of the scientific data gathered by the Expedition is still in current use.

As Herdman writes to Ewart, he became involved in Wyville Thomson’s ‘Challenger Office’ after graduating from the University of Edinburgh in 1879. He was given the collection of Tunicata (a group of marine organisms) to investigate, a work which he continued after he departed for Liverpool in 1881, and which was to be published as a report in three parts between 1882 and 1888. It was research that he evidently enjoyed: he wrote to Ewart of his ‘luck to have a lot of weird deep sea forms to describe which were of course new to science, so I was able to add some new morphological facts.’ Herdman remained in Liverpool for the rest of his career, maintaining a room in the Department of Zoology far beyond his retirement. He was also a generous benefactor to the University of Liverpool, endowing two chairs and funding a geological laboratory. He established biological stations on Anglesey, in Barrow, Lancashire and on the Isle of Man, where he also helped to found the Manx Museum in Douglas. He received honorary degrees from several universities, was actively involved with the Royal Society and was knighted in 1922. However, Herdman’s personal life was marred with sadness when his only son was killed in the Somme and his wife died suddenly after a two-day illness. Herdman himself suffered from heart disease, and died on the eve of his daughter’s wedding, after attending a family dinner in London. His obituary in Nature (2857, 114, 02 August 1924) states that ‘Sir William Herdman’s life, if it is ever written, will be an inspiration to every man, whether he is interested in science or not.’ In his own life summary which he provided to Ewart however, Herdman retains his characteristic self-deprecation, concluding the letter thus: ‘Oh – finally, I have probably made quite as many mistakes as any other zoologist who has ranged over a pretty wide field of work.’

Edinburgh University Library Special Collections also holds the HMS Challenger Papers: http://www.archives.lib.ed.ac.uk/catalogue/cs/viewcat.pl?id=GB-237-Coll-46&view=basic