Being lucky, as I am, to work with a wide variety of archival collections relating to the history of animal genetics in Edinburgh, it can be mightily difficult to select an all-time ‘favourite’ item. However, it was ‘make-up-your-mind time’ last month at the University of Edinburgh’s Innovative Learning Week, when myself and several colleagues from the Centre for Research Collections were invited to give a Pecha Kucha (a fast-paced and time-controlled) presentation on our favourite items or aspects of the collections with which we work.

Being lucky, as I am, to work with a wide variety of archival collections relating to the history of animal genetics in Edinburgh, it can be mightily difficult to select an all-time ‘favourite’ item. However, it was ‘make-up-your-mind time’ last month at the University of Edinburgh’s Innovative Learning Week, when myself and several colleagues from the Centre for Research Collections were invited to give a Pecha Kucha (a fast-paced and time-controlled) presentation on our favourite items or aspects of the collections with which we work.

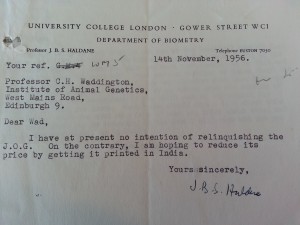

For me, there were a few strong contenders, but the ultimate winner had to be a photograph album presented to C.H. Waddington, the director of the Institute of Animal Genetics in Edinburgh, by his staff and students on the occasion of his 50th birthday in 1955.

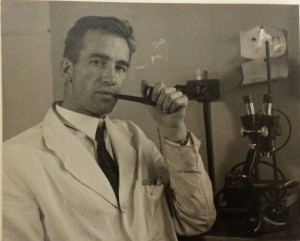

The beautifully presented volume is still in perfect condition and contains a wonderful selection of photographs, all with careful names and annotations. The more formal portraits of staff and scientific researchers give a unique insight into laboratory and research work in the 1950s. In terms of white coats and microscopes, not much has changed today, but I’m not so sure about this suave example of pipe-smoking!

The album also contains pictures of individuals who don’t always feature in the official histories of Edinburgh’s animal genetics community, including the scientists’ wives. The Institute was sometimes rumoured to be a hotbed of scandal and intrigue, so one would like to have been a fly on the wall at this particular party…

I also love the informal and humorous photographs in the album, which paint a much more individual and human picture of the geneticists’ lives and working environment than can be gained simply through printed papers, research reports and official correspondence. Who can fail to be inspired by pictures of an amateur ballet based on the fruit fly Drosophila, for example?

You can watch a video of the Pecha Kucha here: http://vimeo.com/87273640