It’s nearly Hallowe’en, when spooky subjects are foremost in our minds. An ideal time, then, to look at some rather unusual correspondence from the Richard Alan Beatty archive about Egyptian mummies! At first glance, this might seem an unlikely research subject for a reproductive physiologist, but Beatty had his reasons. Writing from the Institute of Animal Genetics to the Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum in July 1977, Beatty asks whether he may have a sample of ‘a testis of an Egyptian mummy’ to enable him to assess whether ‘ certain aspects of chromosome structure and spermatozoan morphology are stable’. In his letter, Beatty realises his request may be a ‘long shot’, but if it worked, ‘it could make an entertaining letter to Nature.’

Beatty was to be disappointed at first. He received a reply three days later from the Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum regretting that, as all their mummies were still in their wrapped state, the Museum could not allow any ‘surgical operation’ to take place. In reply, Beatty understands this restriction, but wonders if he could obtain any mummified cats instead, as ‘there would be merit in looking first at a mummy of some mammal other than man.’ He adds: ‘I read that 100,000 mummified cats were sold for fertiliser in the last century, and this made me hope that cats are in plentiful supply!’ However, he learned that those mummified animals in the Department’s collection were wrapped as well, and so also unavailable for study.

However, Beatty was directed to the Museum’s Department of Zoology, where he had better luck. This Department boasted a collection of mummified ‘monkeys, cats, dogs, and mongooses’, and were happy to let Beatty take a testis sample from an adult male dog from the W.M. Flinders Petrie collection, which was in an unwrapped state. He would also be permitted a sample from a human mummy in the Department of Palaeontology. Beatty visited the Museum on 16 December 1977 to take his samples, having been advised that ‘a strong sharp scalpel’ would be needed, the consistency of the mummified tissue being like ‘very hard leather’. Ever prepared, Beatty tested out his scalpel on ‘an old leather boot’ beforehand!

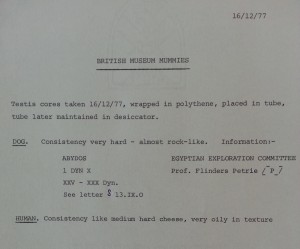

From a report amidst the correspondence, it appears Beatty was eventually successful in getting his samples from the dog and human mummies:

Testis cores taken 16/12/77, wrapped in polythene, placed in tube, tube later maintained in dessicator.

Dog: Consistency very hard – almost rock-like…

Human: Consistency like medium hard cheese, very oily in texture.

It is not clear from Beatty’s archive exactly what resulted from his research on the Egyptian mummies – so we’d be delighted to hear from anyone who may know more about it! In the meantime, you can read more about the strange story, mentioned by Beatty, of the 180,000 mummified cats brought over to England from Egypt in the nineteenth century to be used as fertiliser here:

http://www.strangehistory.net/2013/12/18/tens-of-thousands-of-egyptian-mummies-in-english-soil/

Happy Hallowe’en everyone!

Clare Button

Project Archivist