Giving lectures is a prominent aspect of working life for many academics, as the animal genetics archives here at Edinburgh University Library Special Collections show. Most of the collections of scientists’ personal papers contain information relating to academic and public lectures given, and frequently also include copies of the lectures themselves, some dating back as far as the 1940s. This material gives a fascinating insight into how genetics teaching has changed and evolved over the decades, but we don’t always hear about the experience of lecturing from the point of view of the listening students. Anecdotes occasionally survive about teachers who were particularly memorable (for both good and bad reasons!). James Cossar Ewart, Professor of Natural History at the University from 1882-1927, was instrumental in establishing genetics as an academic subject at the University of Edinburgh in the early twentieth century, but his reputation as a lecturer is not quite as gilded. One of his students, Maurice Yonge, remembered that Ewart’s lectures were ‘conducted amid scenes of riot and general pandemonium, Ewart…being unable to control the class. Indeed, at times…so chaotic were the proceedings, that only the movement of Ewart’s large walrus moustache indicated he was still lecturing.’ On the other hand, the first director of the Institute of Animal Genetics, F.A.E. Crew, was a charismatic and inspiring teacher, as his friend and colleague Lancelot Hogben recalled: Continue reading

Monthly Archives: June 2014

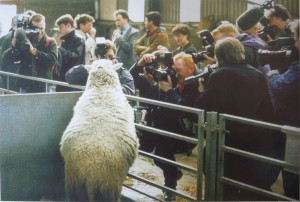

Science: Media Friendly?

Nowadays we are more than accustomed to scientists appearing on television and radio to talk about their research or engage in debates about the social, political and ethical implications of science. The archives of the Roslin Institute and the personal papers of Ian Wilmut testify to the increasingly public-facing role of scientists, which a glance at the file upon file of press enquiries about Dolly the sheep reveals. In the book The Second Creation, Ian Wilmut states that ‘nothing could have prepared us for the (literally) thousands of telephone calls, the scores of interviews, the offers of tours and contracts and in some cases the opprobrium’ which would follow the announcement of Dolly’s birth. The relationship between science and the media can be a prickly one – Dolly’s birth led to hysterical press reactions about potential human cloning – but it also allows for open public debate about the wider implications of scientific research which can affect us all.

Historically, we can trace the continuing increase in scientists’ public presence in tandem with the growth of the media industry throughout the twentieth century. The personal papers of Alan Greenwood and C.H. Waddington reveal that they actively utilised television and radio as forums for their work.

One of the earliest examples in the archives dates from 1936. Australian poultry geneticist Alan Greenwood‘s papers refer to two BBC radio broadcasts given by him titled ‘Junior Geography: the Empire Overseas’. There is also a copy of Greenwood’s script about the Australian outback for the Scottish Sub-Council for School Broadcasting, which begins ‘Good Afternoon, Boys and Girls – To-day we are going to make an excursion into the Australian Bush…’

C.H. Waddington supplemented his professional duties as lecturer, researcher, writer and director of the Institute of Animal Genetics with frequent appearances on television and radio, as his archives reveal. During the 1960s, for example, he participated in BBC broadcasts debating and discussing the existence of God, ‘the appearance of design in evolution’, Lysenkoism, and the social implications of biological research, most notably in the controversial programme ‘Towards Tomorrow: Assault on Life’, broadcast in December 1967. Waddington very much saw the biological sciences as woven closely into the fabric of society, with public debate an important facet of this. Writing to Waddington about his appearance on the BBC series ‘Some Aspects of Modern Biology’ in March 1967, science correspondent and adviser Gerald Leach wrote that ‘you were the only scientist that I’ve seen in this series who had any kind of feeling at all that one might set up social goals and try and work towards them.’

These ‘social goals’ are an important aspect of scientific research. Contentious as the media’s portrayal of science and scientists can often be, it puts a human face to specialist terminology, complex theories and vast data sets. It broadens our awareness of scientific discovery and its potential for the world and, importantly, allows us to respond.

Clare Button

Project Archivist